The admiral who spoke at the graduation of my pre-commanding officer (PCO) course in 2001 got our attention by saying, “Your whole career, you have heard that your priorities should be ship, shipmate, self. In command, you have to turn that on its head. If you do not take care of yourself—eat, sleep, exercise, and stay sharp—you will fail your ship and crew.” I came to realize he was absolutely right.

The Surface Navy is slowly catching up with the science of sleep and its importance to military operations, but even with this new focus on crew endurance and fatigue, one person could get lost in the discussion: the commanding officer (CO).

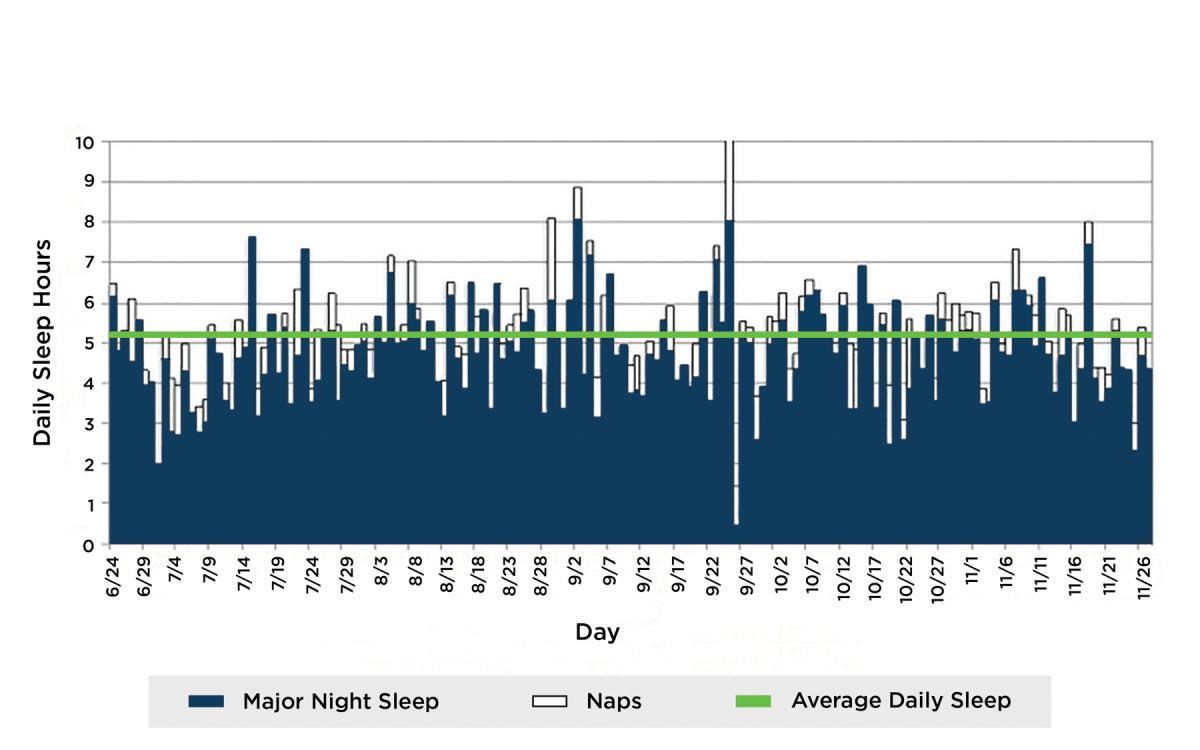

The human body needs at least 7 hours of good quality sleep, no matter what uniform or insignia it wears. Jonathan Shay, a noted sleep researcher, makes an excellent case for a moral and ethical imperative of “self-care” by the commanding officer.1 He cites numerous instances where a sleep-deprived commander made bad decisions and endangered his crew. Dr. Nita Shattuck and Dr. Panagiotis Matsangas of the Naval Postgraduate School conducted a unique and first-of-its-kind case study using an actigraph or “sleep watch” worn by a destroyer commanding officer in 2012 through an entire deployment. The data showed chronic sleep deprivation throughout; the CO slept, on average, only 5.2 hours per 24-hour period, which included frequent naps to “pay down” sleep debt. But Shattuck and Matsangas note that this was not nearly enough, and given the number of disruptions a CO endures each night, fatigue is even worse. Taken together, this resulted in a state of chronic fatigue, with predicted cognitive effectiveness during approximately 15 percent of the deployment equivalent to a person with a blood alcohol concentration of 0.08 percent, i.e., “legally drunk.”2 (See Figure 1.)

Continuing the theme of linking “self-care” to what he calls “moral reasoning,” Olav Olsen asserts that “the moral imperative of sleep” goes even further, insisting that a commander owes it to his troops to rest so that he/she is prepared for battle, and citing several instances in history when an engagement may well have been decided by the amount of sleep the commander had received just before battle in both a naval and land-based setting. A former CO of mine reminded me that “you go into combat with the sleep you have.” Having stood a variety of watch rotations and commanded two ships, I know this all too well.

In 2001, while in command of the USS Oscar Austin (DDG-79), my own self-induced sleep deprivation directly contributed to a significant injury for one of my sailors. During a long at-sea boarding exercise that went well into the evening and beyond its planned duration, we were maintaining station on the training vessel while ferrying the boarding team back and forth using the rigid-hull inflatable boat (RHIB). Focused on the port side, where we were getting too close to the training vessel, I forgot that we had given permission for the RHIB to come alongside to starboard. I had to give a strong backing bell, and the screw wash lifted the RHIB and spilled the crew—all six of them—into the water. One was injured by the RHIB propeller, and all were in the cold, dark water for nearly 30 minutes while we launched the other RHIB to fish them out. After dealing with the worst injuries of one sailor (who eventually recovered), I collapsed in a heap and felt sick about the way my fatigue had contributed to, if not caused, this bad decision. I failed, and someone got hurt. I never forgot that lesson, and I hope others will learn from it. Dr. Shay calls it “droning” when the body is awake, but the mind is asleep.

For the CO and other key individuals such as the officer of the deck and tactical action officer, the potential for droning is more than a personal safety issue and may be the key to a successful—or failed—tactical engagement. I had another eye-opening experience in command of the USS San Jacinto (CG-56) when we conducted an exercise with a foreign diesel submarine in the Mediterranean. Following an intense three-day exercise, we held a debrief where each of the ship COs discussed tactics and what we were thinking at the time. The CO of the opposing submarine shared that it was not our tactics that led to our victory: His insight was that we had kept them in shallow water for nearly 36 hours. Because his navy requires the CO’s presence on the bridge during shallow operations, he got so tired he made a tactical mistake. As noted in the article by Olav Olsen, “Sleep deprivation led to an overall increase in permissiveness in terms of judging difficult courses of action to be appropriate.”3 In other words, while fatigue does impact motor skills and reaction time, a more important consequence for the commander may be a directly negative impact on the ability to make a decision. It had not occurred to me that impacting the adversary’s sleep might be the best weapon in my arsenal. Dr. Shay knew this, stating “Attacking an enemy’s sleep has the same effect as depriving them of food and supplies.”

It is long past the time to recognize that we are human, and that self-care is a commander’s responsibility to him/herself and the crew. While there is value in knowing your body’s limits, the idea that you can train your way out of fatigue is a fallacy. The science undeniably supports it.

But how to turn this responsibility into practice? Certainly, a CO on a ship underway must be available 24/7 for contact reports, to make critical tactical decisions, and to mentor and train the crew, but there are ways to plan ahead and set priorities.

- Set sleep goals. The Naval Surface Forces Crew Endurance instruction requires 7 hours of sleep either in one sitting or a shorter session followed by a nap. Work this into your plan for the day.

- Delegate. The XO is supposed to fleet up, so work out times when you can sleep and let him or her take reports and mentor the bridge. He/she will rise to the occasion.

- Use technology. There are a lot of biometric devices and apps to help you track your sleep and activity.

- Value sleep. Keep a routine, to include naps when appropriate.

- Trust your crew. Empower them to speak up when they note that you are getting tired or have been up for too long. Expect the same for them.

- Educate yourself. I am always amazed that intelligent, educated officers can be dismissive of the science of sleep. The NPS Crew Endurance website has a wealth of information, and you can find much more information online.4 The articles referenced here are a start.

The safe operation of a ship requires planned maintenance for all equipment, and this applies to people, too. We often hear leaders say, “The crew is the most important part of the ship.” But COs must realize everyone is watching; indifference to crew fatigue (including their own) can send a message that “getting the job done”—even a peacetime mission—is more important than ship or individual safety. Leaders would never tolerate “gun decking” or omission of planned maintenance on ship’s equipment, so they should not ignore the obligation to maintain themselves by getting their required sleep.

1. Jonathan Shay, “Ethical Standing for Commander Self-Care—The Need for Sleep,” Parameters, U.S. Army War College Quarterly, Summer 1998, pp. 93–105. https://ssi.armywarcollege.edu/pubs/parameters/articles/98summer/shay.htm.

2. Nita Shattuck and P. Matsangas, “A 6-Month Assessment of Sleep during Naval Deployment. A Case Study of a Commanding Officer,” Aerospace Medicine and Human Performance, Vol. 86, May 2015.

3. Olav Olsen, “The Impact of Partial Sleep Deprivation on Moral Reasoning in Military Officers,” Sleep, Vol. 33, 8 Nov 2010, https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/33.8.1086.

4. Department of the Navy Crew Endurance Handbook: A Guide to Applying Circadian-Based Watchbills, version 1.1, 5 October 2017, Naval Postgraduate School, http://nps.edu/crewendurance.