The 1982 Falklands War makes an excellent case study for the U.S. Navy, as it prepares for potential fights with the People’s Republic of China over contested islands in the western Pacific. There are strong parallels in the political conditions, geographies, and military situations between the Falklands War and today’s hot spots in the Senkaku, Spratly, and Paracel islands and elsewhere.

British Admiral John Forster “Sandy” Woodward, the Falklands task force commander, wrote that the “British victory would have to be judged anyway as a fairly close run thing. . . . We fought our way along a knife-edge.”1 Examining the lessons of the 1982 fight between Argentina and Great Britain may give the U.S. Navy the advantage it needs to succeed in a future fight along a knife edge.

Oceans Apart but Closely Related

Argentina has intermittently contested the 18th-century British claim to the Falkland Islands that Captain John James Onslow reasserted in 1833.2 In early 1982, tensions over the islands were especially high, yet neither side thought they would lead to war. Britain did not believe Argentina would be so brash as to invade, whereas Argentina believed Britain unwilling to fight over the possession in the age of decolonization.3 There was little financial or strategic reason to fight for the Falklands, except their political and symbolic value.

Similarly, the Senkakus and other islands have been contested by China, Taiwan, and Japan for decades. It is easy to imagine a political situation like that of the Falklands leading to a Sino-American war. China might look to seize contested islands to distract its population from domestic problems, issuing ultimatums and making military preparations for invasion. The United States could dismiss those moves as mere posturing, which China could misinterpret as the United States signaling it would not go to war over the islands. The result could again be war over territory neither side wanted to fight for.4 As Woodward wrote en route in the Atlantic, “Of course, there’s no way the Falklands are worth a war, whether we win it or not—equally, there’s no way you should let the Argentinians (or anyone else for that matter) get away with international robbery.”5

The Senkakus, for example, share some geographic similarities with the Falklands. The Falkland Islands are small and inhospitable, with a tiny population, deep water to the east, and nearby shallow littorals. The uninhabited Senkakus are much the same, with their shallow water in the East China Sea. Distance defined the war. Argentina sits a mere 400 nautical miles (nm) from the Falklands—Britain, approximately 7,800.6 Distance forced the Royal Navy to fight largely unaided by the Royal Air Force, strained the fleet’s logistics, and necessitated use of the nearest base—at Ascension Island, 3,300 nm away.7 Similarly, the Senkakus lie quite close to China, just 220 nm away—but more than 5,000 nm from the United States. Just as the Royal Navy had to operate from Ascension, the U.S. Navy may be forced to rely on Guam and Hawaii as its primary bases if closer spots such as Okinawa become unavailable.8

Finally, the military situations in both cases have important parallels. Each features adversaries with technologically advanced militaries, but global obligations kept the Royal Navy (and could keep the U.S. Navy) from bringing all its forces to bear against an enemy able to devote its entire fleet to the fight. In addition, politics and a desire to limit the conflict’s scope prevented British attacks on Argentina proper. Similar restraint likely would stop the United States from attacking mainland China.9

Undersea Warfare Lessons

Argentina invaded the Falklands on 2 April 1982, easily capturing them.10 Three British nuclear-powered submarines arrived off the islands less than two weeks later.11

On 1 May, one of those submarines, HMS Conqueror, found the cruiser General Belgrano and two escorts near the shallow water of Burwood Bank, south of the Falklands. The next day, the Conqueror sank the cruiser, scoring two hits from a mere 1,400 yards away.12 That single attack “sent the navy of Argentina home for good,” Woodward wrote.13 Acknowledging its weak antisubmarine warfare (ASW) capabilities, Argentina withdrew its surface fleet to port for the remainder of the war.

This left the submarine ARA San Luis as the single Argentine warship at sea for most of the war. Despite facing the entire British task force on its own, the San Luis completed a five-week patrol unscathed. She staged attacks on British warships but missed each time because of torpedo system malfunctions.14 Meanwhile, British ASW efforts against that single target proved futile. The British fired an astonishing 200 torpedoes at false contacts over five weeks, rapidly depleting their inventory. As Sir Lawrence Freedman dryly wrote in the conflict’s official history, because of ASW anxieties, “the Atlantic whale population suffered badly during the course of the campaign.”15

The Royal Navy’s success with its submarine fleet and remarkable frustrations with ASW provide insights into how the U.S. Navy could prepare to fight for undersea supremacy around islands such as the Senkakus.

Despite how concerned Woodward was about the threat the General Belgrano group posed to his task force, the Conqueror had to wait 27 hours between locating the cruiser and receiving rules of engagement (ROE) from London permitting an attack outside the declared exclusion zone.16 If the cruiser had gotten away during the wait, the political ramifications would have been troubling, especially if the cruiser had been able to threaten the British carriers because the Conqueror had had to wait for permission to attack an enemy already in her reticles. U.S. submariners should be prepared to interpret and fight using complex ROE, which the Navy must prepare ahead of time; most conflicts will be complex and not a binary distinction between peace and unrestricted warfare.

The Falklands War also showed how inadvisable it is to use submarines for anything other than surveillance or destruction of enemy warships. British helicopters attacked and disabled a second submarine, the ARA Santa Fe, while she was surfaced completing an inconsequential troop and supply delivery. The result was the loss of half of Argentina’s operational submarines for little gain.17 Stealth makes submarines ineffective at presence missions or deescalating tense political situations; the General Belgrano had no indication that an enemy submarine was present until two torpedoes ripped open her hull. U.S. Navy leaders should keep submarines focused on the missions they do best.

When submarines are unleashed on enemy shipping, the results can be decisive. The single submarine Conqueror launched a single salvo that sank a single ship—and in doing so, defeated an entire navy with a “devastating deterrent impact.”18 The U.S. Navy should strive to ensure its submarine force is capable of similar feats in what former Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Jonathan Greenert describes as “the one domain in which the United States has clear maritime superiority.”19 That superiority will be at risk throughout the coming decade, as the Navy’s submarine inventory drops toward a forecast low of 42 fast-attack submarines in 2028 and China rapidly improves its platforms, sensors, and weapons.20

The Navy’s undersea edge will need to be rooted in superior training; however, too much time that should be devoted to preparing for the high-end fight instead is spent on extraneous tasks.21 Antiaccess weapons likely will force the submarine fleet to fight the opening stages of any war in the western Pacific alone. Before the Navy sends 31 submarines to take on a Chinese fleet comprising 129 ASW-capable warships, 60 submarines, and dozens of ASW aircraft, it must do everything possible to ensure those attack crews are truly ready for war.22

British frustrations with ASW also are instructive. The U.S. Navy report on the Falklands stated:

The Royal Navy, long believed to be the best equipped and trained Navy in the Free World in the field of shallow water ASW, was unable to successfully localize and destroy the Argentine submarine San Luis, known to be operating in the vicinity of the task force for a considerable period.23

That single Argentine submarine faced an entire task force and did not hit a single target, yet it “created enormous concern . . . [and] dictated, at least as much as did the air threat, the conduct of British naval operations.”24

Confronted by dozens of Chinese submarines in the western Pacific, the U.S. Navy will be faced with a significantly more challenging problem.25 It can prepare for that fight now by increasing ASW training and developing the quantity and quality of ASW platforms. Most important, the U.S. Navy should realize that if the entire British task force could not find a single Argentine submarine in a month, then securing the Chinese near seas for carrier strike group operations, the key to U.S. naval warfare, could take years.

Surface Warfare Lessons

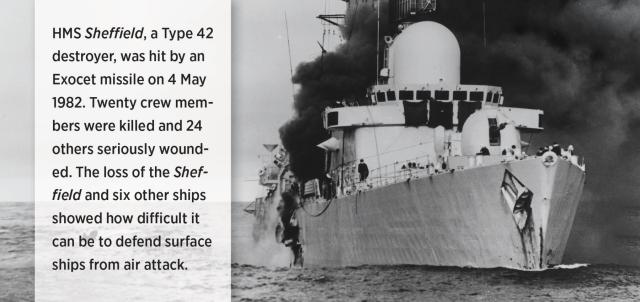

With the Argentine Navy neutralized before the British surface fleet approached the Falklands, the British refocused on defeating the air threat to land troops to recapture the islands. That fight started off with a shock when a Super Etendard jet launched an Exocet antiship missile and sank the destroyer HMS Sheffield.26 Journalists Max Hastings and Simon Jenkins wrote:

It would be difficult to overstate the impact of Sheffield’s loss upon the British task force. Officers and men alike were appalled, shocked, subdued by the ease with which a single enemy aircraft firing a cheap—£300,000—by no means ultra-modern sea-skimming missile had destroyed a British warship specifically designed and tasked for air defence.27

After the sinking, the war became a battle for air supremacy as the Argentinians attacked British ships primarily defended by Harriers and missile defense systems. Despite gaining the upper hand, by late May the British had not achieved control of the skies sufficient to ensure a safe amphibious landing. The Argentinians were husbanding much of their air strength, waiting to unleash it on the vulnerable amphibious ships and escorts. Worsening weather and a stretched supply train meant the British needed to execute that assault soon or be forced to withdraw.28

Royal Marines landed on 21 May at San Carlos, an isolated location across the island from the capital of Port Stanley. The troops landed without a single casualty, but Argentine aircraft attacks on the exposed ships were “indescribable in their ferocity.”29 Despite a tenacious defense, British ships suffered mightily. On the first day alone, only two of the seven warships that entered San Carlos Bay escaped unscathed.30 For the remainder of the war, the surface fleet provided gunfire support and supplies to the Royal Marines as they fought their way across the island, capturing Port Stanley and ending the war approximately three weeks later.

The history of the Falklands War demonstrated how difficult it will be to hide surface ships in a fight in the western Pacific. In the air, Argentine Boeing 707 transport—not reconnaissance—aircraft detected and tracked the British task force as it transited south, first gaining contact days before the British thought possible.31 Super Etendard pilots analyzed Harrier radar contacts to surmise the location of the strike group, then used that data to launch the Exocet attack that destroyed the transport SS Atlantic Conveyor.32 Around the Falklands, Argentina discretely employed five surveillance trawlers to report the position of the British task force.33

China’s ability to detect and track a U.S. surface group will be much greater than Argentina’s was. China has dozens more surveillance aircraft, a first-rate unmanned aerial vehicle program, and a robust satellite network that, according to the U.S. Office of Naval Intelligence, allows China to “observe maritime activity anywhere on the earth.”34 And China can rely on its massive People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia—hundreds of trawlers and merchants, camouflaged among the thousands of civilian ships in the Chinese near seas—to discreetly and accurately report U.S. warship locations.35

When the Chinese do find the U.S. surface fleet, the Falklands also show how difficult it will be to defend against air and missile attacks. Even if U.S. missile defenses are perfect, the sheer number of incoming missiles and aircraft could overwhelm them. Today, a single Chinese Houbei missile craft has more antiship missiles than the entire Argentine military had in 1982, and China is estimated to have thousands overall.36

British casualties—four warships lost (and one a mission kill) plus two auxiliaries destroyed—indicate that when U.S. escorts are hit, modern munitions will typically incapacitate or sink them. Multiple Argentine Exocets and bombs did not explode because of fuzing problems, and Woodward acknowledged that Britain “would surely have lost” five more ships if Argentine weapons had functioned properly.37 In the age of anti-ship missiles and one-hit ships, the U.S. Navy’s reliance on a small number of large capital ships may prove a brittle plan.38

Carrier and Air Warfare Lessons

The struggles with hiding and defending the fleet led to difficult questions about how best to use Britain’s two small aircraft carriers, HMS Hermes and Invincible. They were the greatest assets in the British task force and their air wings the best defense against Argentine air attacks.39 They also were the greatest British vulnerability, however, and they dictated the deployment and tactics of the entire task force. Woodward wrote of the “inescapable truth that the Argentine commanders failed inexplicably to realize that if they had hit Hermes, the British would have been finished. They never really went after the one target that would surely have given them victory.”40 Woodward’s solution was to keep the carriers as far out to sea as possible, almost exclusively using them for air defense.

The Navy should consider something similar for its carriers in the western Pacific. Focusing on air defense would allow the carriers to execute a mission they can do best, preserving the rest of the fleet for tasks they are better suited to perform, such as antisurface warfare and strike in contested environments. In an air defense posture, carriers can remain farther out to sea to reduce the likelihood of Chinese attacks, mitigate the reduced range of the air wing, and avoid the risk of losing valuable fighters to formidable Chinese air defenses.41

The Falklands War shows that carriers will remain necessary despite a likely diminished role near any contested islands. They were the only reliable source of British air power; the Royal Air Force’s only land-based contribution was seven Vulcan bomber attacks flown from faraway Ascension Island, which required 17 in-flight refuelings and had “virtually no impact.”42 Numerous Argentine attacks were stopped by the mere presence of Harriers, despite the lack of airborne early warning—a weakness U.S. carriers would not face.43

Winning In WestPac

A former commander of the U.S. Atlantic Fleet wrote that the Falklands War is a “gold mine of lessons.”44 As tensions continue to rise around the western Pacific’s contested island chains, the Navy should look to mine that seam to prepare.

Today’s officers and sailors should study the war to draw their own conclusions; the Chinese are doing so.45 Every effort matters in a fight resting on a knife edge, and so we must out-study them if we hope to outfight them.

1. ADM Sandy Woodward, RN, One Hundred Days: The Memoirs of the Falklands Battle Group Commander (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1992), xviii.

2. Max Hastings and Simon Jenkins, The Battle for the Falklands (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1983), 5.

3. CDR Kenneth R. McGruther, USN, “When Deterrence Fails: The Nasty Little War for the Falkland Islands,” Naval War College Review (March/April 1983): 48, 50.

4. Michael E. O’Hanlon, The Senkaku Paradox: Risking Great Power War Over Small States (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press, 2019), 38–40.

5. Woodward, One Hundred Days, 81.

6. Lawrence Freedman, The Official History of the Falklands Campaign, Vol. 2: War and Diplomacy (London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2005), 49.

7. Office of Program Appraisal, “Lessons of the Falklands” (Washington, DC: Department of the Navy, February 1983), 16.

8. Robert Haddick, Fire on the Water: China, America, and the Future of the Pacific (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2014), 91.

9. McGruther, “When Deterrence Fails,” 52.

10. Richard C. Thornton, The Falklands Sting (Washington: Brassey’s, Inc., 1998), 130.

11. Freedman, The Official History of the Falklands Campaign, 50.

12. Freedman, 292.

13. Woodward, One Hundred Days, 164.

14. Jorge R. Bóveda, “One against All: The Secret History of the ARA San Luis During the South Atlantic War,” Naval Center Newsletter, April 2007, www.irizar.org/816boveda.pdf.

15. Freedman, The Official History of the Falklands Campaign, 214, 728.

16. Freedman, 289.

17. David Brown, The Royal Navy and the Falklands War (London: Leo Cooper Ltd., 1987), 101.

18. CDR Christopher Craig, D.S.C, RN, “Falkland Operations II: Fighting by the Rules,” Naval War College Review (May/June 1984): 24.

19. VADM Michael J. Connor, USN, “Advancing Undersea Dominance,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 144, no. 1 (January 2015).

20. Ronald O’Rourke, “Navy Virginia (SSN-774) Class Attack Submarine Procurement: Background and Issues for Congress” (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, 17 May 2019), 9.

21. LT Jeff Vandenengel, USN, “A Deckplate Review: How the Submarine Force Can Reach Its Warfighting Potential,” Center for International Maritime Security, 30 April 2018, cimsec.org/deckplate-review-submarine-force-can-reach-warfighting-potential-pt-1/36235.

22. U.S. Department of Defense, “Annual Report to Congress: Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China” (Washington, DC: Office of the Secretary of Defense, 2019), 116.

23. Office of Program Appraisal, “Lessons of the Falklands” (Washington, DC: Department of the Navy, February 1983), 47.

24. ADM Harry D. Train II, USN (Ret.), “An Analysis of the Falkland/Malvinas Islands Campaign,” Naval War College Review (Winter 1988): 40.

25. U.S. Department of Defense, Annual Report to Congress: Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China (Washington, DC: Office of the Secretary of Defense, 2018), 29.

26. Woodward, One Hundred Days, 14, 21.

27. Hastings and Jenkins, The Battle for the Falklands, 155.

28. Hastings and Jenkins, 161.

29. Commander Nick Kerr, RN, “The Falklands Campaign,” Naval War College Review (November/December 1982): 19.

30. Freedman, The Official History of the Falklands Campaign, 467.

31. Freedman, 215.

32. CDR Jorge Luis Colombo, ARA, “Falkland Operations I: ‘Super Etendard’ Naval Aircraft Operations during the Malvinas War,” Naval War College Review (May/June 1984): 19.

33. Freedman, The Official History of the Falklands Campaign, 256.

34. Office of Naval Intelligence, “The PLA Navy: New Capabilities and Missions for the 21st Century” (Washington, DC: Office of Naval Intelligence, 2015), 19, 22.

35. Andrew S. Erickson and Conor M. Kennedy, “China’s Maritime Militia,” Center for Naval Analyses, 7 March 2016, www.cna.org/cna_files/pdf/Chinas-Maritime-Militia.pdf.

36. Dennis M. Gormley, Andrew S. Erickson, and Jingdong Yuan, A Low-Visibility Force Multiplier: Assessing China’s Cruise Missile Ambitions (Washington, DC: National Defense University Press, 2014), 16.

37. Woodward, One Hundred Days, xviii.

38. CDR Phillip E. Pournelle, USN, “The Deadly Future of Littoral Sea Control,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 141, no. 7 (July 2015).

39. Kerr, “The Falklands Campaign,” 21.

40. Woodward, One Hundred Days, xviii.

41. CAPT Henry J. Hendrix, USN (Ret.), “Retreat from Range: The Rise and Fall of Carrier Aviation.” Center for a New American Security, October 2015, www.cnas.org/publications/reports/retreat-from-range-the-rise-and-fall-of-carrier-aviation.

42. Office of Program Appraisal, “Lessons of the Falklands” (Washington, DC: Department of the Navy, February 1983), 6.

43. Hastings and Jenkins, The Battle for the Falklands, 217.

44. Train, “Falkland/Malvinas Islands Campaign,” 50.

45. Christopher D. Yung, “Sinica Rules the Waves? The People’s Liberation Army Navy’s Power Projection and Anti-Access/Area Denial Lessons from the Falklands/Malvinas Conflict,” in Chinese Lessons from Other Peoples’ Wars, Andrew Scobell, David Lai, and Roy Kamphausen, eds., U.S. Army War College Strategic Studies Institute (November 2011), 75.