In 2017, several online news articles highlighted a research study released by Protect Our Defenders (POD), a national advocacy group.1 The overall conclusion of the study report is that disparities exist within the military justice system that trend negatively for racial and ethnic minorities, African Americans in particular. Based on raw data obtained from the individual uniformed services via Freedom of Information Act requests, the report showed “for every year reported and across all service branches, black service members were substantially more likely than white service members to face military justice or disciplinary action, and these disparities failed to improve or even increased in recent years.”2 For other racial and ethnic groups, there was evidence they “may have higher military justice or disciplinary involvement than white service members.”3

The POD report highlights discipline disparities that align with the substantial existing body of research regarding inherent or implicit bias. Implicit bias “refers to the attitudes or stereotypes that affect our understanding, actions and decisions in an unconscious manner. These biases, which encompass both favorable and unfavorable assessments, are activated involuntarily and without an individual’s awareness or

intentional control.”4 Implicit bias can take the form of positive or negative stereotypes across many topics, but the most impactful are the negative biases that revolve around race, gender, age, sexual orientation, and disability. Of note, “a wealth of research convincingly demonstrates that even well-meaning persons with no desire to exhibit racial animus nonetheless act under the influence of unconscious biases that systemically affect others on the basis of race.”5

The persistence of disparities documented in the POD report strongly suggests the existence of implicit racial/ethnic bias among decision-makers in the military justice system.6 While the statistical discipline disparities in aggregation likely are not due to purposeful, conscious (explicit) bias, they produce the same effect: an outsized, quantifiable difference in military justice actions that adversely affect racial/ethnic minorities at greater rates than their nonminority military counterparts.

Study Findings

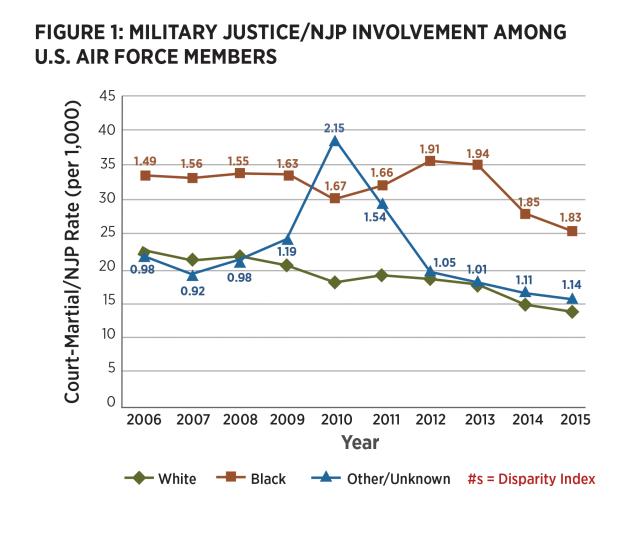

According to POD’s findings, for the U.S. Air Force, between 2006 and 2015, African American airmen were 71 percent more likely to experience military disciplinary involvement—court-martial or nonjudicial punishment (NJP)—than white airmen.7

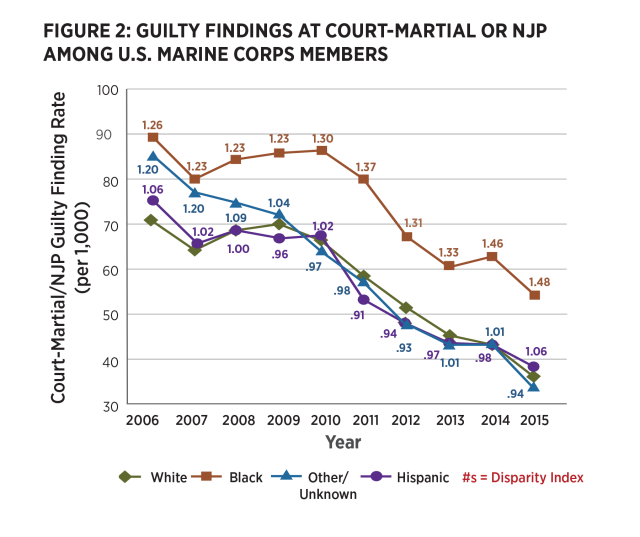

For Marine Corps members, between 2006 and 2015, African American personnel were 32 percent more likely than their white counterparts to receive a guilty finding at court-martial or NJP. Across the nine years, this disparity ranged from 23 percent to 48 percent more likely and was highest in the most serious forums: “In [an] average year, black Marines were 2.61 times [161 percent] more likely to receive a guilty finding at a general court-martial than white Marines. . . . Overall, the more serious the proceeding, the greater was the disparity between black and white Marines.”8

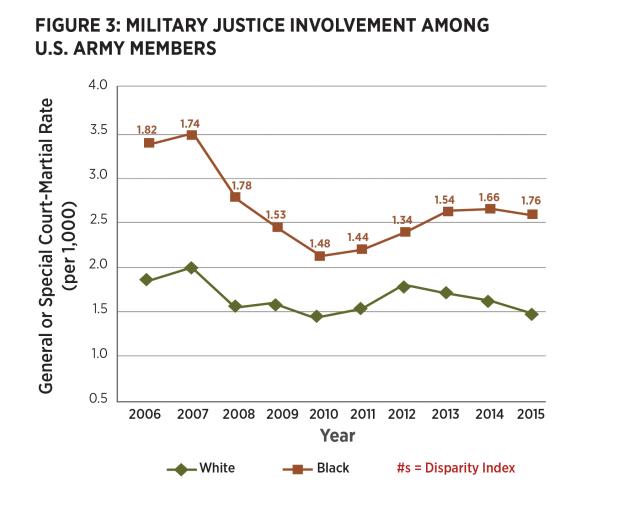

POD’s report indicates the Army also has experienced significant disparity within its military justice system that breaks along racial/ethnic lines. Within the Army, African Americans were 61 percent more likely to face courts-martial compared with white soldiers. “This disparity existed every year from 2006 to 2015, with the disparity index ranging from 1.34 (34 percent more likely) to 1.82 (82 percent more likely).9

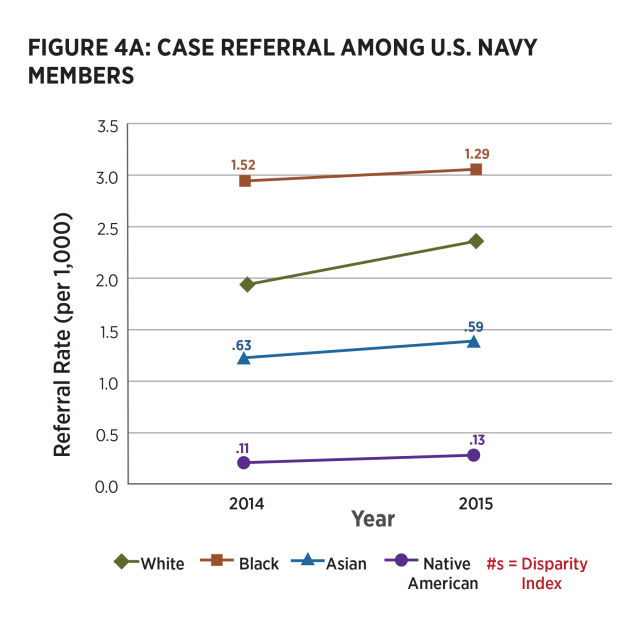

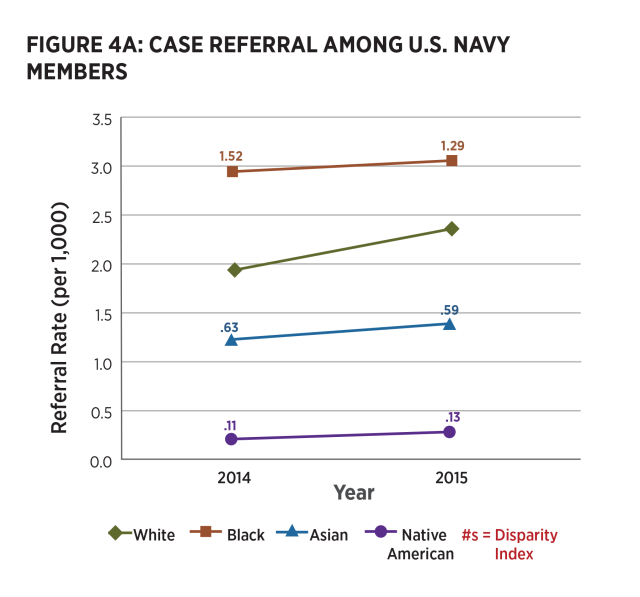

The Navy provided data only for 2014 and 2015; however, this data set contained a rich level of detail regarding military justice or disciplinary action. African American sailors “were more likely than white sailors to have their case referred for military justice proceedings (1.40 times more likely [40 percent more]) and to have military justice or an alternative disposition action taken against them (1.37 times more likely [37 percent more]).”10

In summary, African American sailors were significantly more likely to have military justice and disciplinary cases referred for action and then adjudicated against them than their white counterparts. For sailors of other races/ethnicities, “Hispanic sailors . . . were somewhat more likely than white sailors to be convicted at general or special court-martial. . . . The same pattern was found among Asian service members.”11

Analysis

The all-volunteer force includes a large subset of service members who self-identify as racial or ethnic minorities. For example, the Department of Defense (DoD) reports 31.4 percent of its total active-duty force of 1,288,596 identify as ethnic or racial minorities (17.4 percent as African American), and the Department of the Navy reports 38 percent of its total end strength of 264,640 identify as an ethnic or racial minority (17.2 percent as African American).12 When Hispanic sailors are factored in the Navy demographic, the percentage of ethnic or racial minorities increases to 53.2 percent.13

Minorities tend to serve in numbers equal to or greater than their percentages in the U.S. population.14 Consequently, it is imperative that the all-volunteer military ensure the equity of its military justice system. Simply put, if credible evidence of negative implicit bias continues to accumulate without any visible, effective actions to address it, potential minority recruits may question the decision to volunteer (or for current personnel, to continue to serve). This could lead to a decline in long-term volunteerism rates and a deterioration in the esprit de corps and morale of affected populations similar to that experienced in the 1970s military.

Racial and ethnic implicit bias has been documented in many areas of civilian society, including primary and secondary public schools. For example, the U.S. Department of Education, Office for Civil Rights, reported discipline statistics in which “black students are suspended and expelled at a rate three times greater than white students.”15 In March 2018, the Government Accountability Office published a similarly themed report, noting that, although representing just 16 percent of all public school students, African American “students represented about 39 percent of students suspended from school.”16 Researchers exploring implicit bias at the collegiate level are finding a similar pattern of overrepresentation of racial and ethnic minorities in campus discipline cases.17 These disparities are the tell-tale signs of implicit bias in a system, and the POD report provides evidence of those signs in the military justice system.

The military justice system’s prevailing notion has been that it is largely immune to implicit bias because of the highly structured organization of the military services, which contains numerous oversight activities, monitoring systems, and checks and balances. The presumption is that the extensive training, coupled with laws and regulations governing justice activities, serves as a forcing function to ensure equal justice. However, given the ample evidence to the contrary, it is time to reconsider this assumption.

As the POD explains, “the military is unique in that due to its nature as an employer . . . it acts as a natural though imperfect control for several factors associated with criminal justice involvement. . . . Despite these equalizing factors, racial disparities are present at every level of military disciplinary and justice proceedings.”18 In other words, given that it recruits its own high-quality force, the military should produce racially/ethnically balanced military justice statistics. To the contrary, the system produces an overrepresentation disparity, indicative of implicit bias, similar to the civilian sector.

The Navy (and DoD overall) must take action to address what will become a growing threat not only to recruiting and retention, but also to good order and discipline.

Recommendations

POD proposes four recommendations to address the implicit bias disparities:

- Reform the military justice process to empower legally trained military prosecutors instead of the command of the accused to determine when to refer a case to court-martial.

- Collect and publish consistent racial and ethnic data regarding military justice and outcomes.

- Track data for victims of crimes to determine whether there might be bias regarding victims of particular races or ethnicities.

- Conduct research to assess the underlying causes of existing racial and ethnic discrepancies within the military disciplinary and judicial systems and explore steps to address inequalities.19

Recommendation 1—a leapfrog to more forceful oversight mechanisms, including direct monitoring/intervention by senior Navy staff—is premature. First, preserving the military justice authority of commanding officers and commanders is important and inextricably linked to unit good order and discipline. Second, given the opportunity, most commanding officers and commanders would incorporate recommended training and feedback mechanisms into their military justice decision-making process. They are entrusted with command of sailors; the Navy should give them the first opportunity to address this issue.

Regarding recommendation 2, the four services are widely divergent in how they identify the Hispanic/Latino demographic, which complicates meaningful data collection and analysis. The services should adopt a uniform demographic standard for all races and ethnicities, with emphasis on the Hispanic/Latino population because it has the greatest potential to be undercounted and underrepresented.

The remaining recommendations may be useful for servicewide oversight, but they do not address the core issue: How do we assist commanding officers and commanders, the frontline decision-makers and adjudicators of the military justice system? The Navy must focus its initial efforts on this inflection point as it can provide the largest impact and return on investment. The following recommendations could be easily implemented by the Navy—and equivalent actions could be taken by the other services.

- Provide implicit bias identification training that includes historical context, current impact in the military justice system, processes to recognize bias (within oneself and one’s command), and actions to address it either during the Navy Leadership and Ethics Center’s prospective commanding officer, prospective executive officer, and prospective command master chief/chief of the boat courses or during the Naval Justice School senior leader legal course (or both).

- Provide incumbent commanding officers and commanders with quarterly (electronic) reports on NJP and courts-martial demographic statistics. Meaningful, quantitative data will help reinforce awareness of when implicit bias may be afoot and allow the commanding officer or commander to course correct in situ.

- Collect better (not more) data for analysis. Collection should not become a time and manpower tax levied on operational units, but instead should be derived through better identification, processing, labeling, and curation of the data commands already provide in routine reports. Navy staffs can analyze this relevant data and provide periodic reports to senior leaders on whether discipline rates in aggregate fall in line with demographic percentages. This analyzed data also will help determine whether the recommended interventional training and awareness reports are delivering the desired effects across the Navy.

- Provide focused training for staff judge advocates (SJA)—who advise the flag officers who typically have courts-martial convening authority—and for the trial counsels who prosecute those cases. These individuals play a significant role in deciding whether a case is referred to courts-martial, what charges are brought, and the manner in which the case is pursued—and implicit bias can occur in all these phases. SJAs and prosecutors should receive training during their initial training and periodically through the Trial Counsel Assistance Program. Defense counsel judge advocates should receive similar training during their respective courses.

A Course Correction

Although the POD report and other studies involved racial and ethnic implicit bias, bias also can affect personnel based on their gender, sexual orientation, and even performance (e.g., disparate military justice treatment for golden sailors versus average or troubled sailors). These implicit biases can have a corrosive impact on unit good order and discipline, cohesion, and morale, which harms a command’s esprit de corps and warfighting readiness.

A military justice system that does not deliver discipline equally breaks trust with our sailors. The Navy must take a navigational fix on this issue and correct its course.

1. See Rebecca Kheel, “Advocacy Group Accuses Military Justice System of Racial Bias,” TheHill.com, 7 June 2017; Safia Samee Ali, “Black Troops More Likely to Face Military Punishment than Whites, New Report Says,” NBCNews.com, 7 June 2017; Jeanette Steele, “Black Troops Are Being Prosecuted at Higher Rate than Whites,” San Diego Union Tribune, 7 June 2017; and Brock Vergakis, “Black Sailors More Likely than White Sailors to Be Referred to Court-Martial, Report Says,” The Virginian Pilot, 7 June 2017.

2. D. Christensen et al., “Racial Disparities in Military Justice: Findings of Substantial and Persistent Racial Disparities within the United States Military Justice System,” protectourdefenders.com, 5 May 2017.

3. Christensen et al., “Racial Disparities.”

4. “Understanding Implicit Bias,” Ohio State University Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race & Ethnicity (2018); and R. Banks, J. Eberhardt, et al., “Discrimination and Implicit Bias in a Racially Unequal Society,” 94 CALIF. L. REV 1169 (2006).

5. B. Trachtenberg, “How University Title IX Enforcement and Other Discipline Processes (Probably) Discriminate,” Legal Studies Research Paper Series, no. 2017-22 (2017), 107–55.

6. Christensen et al., “Racial Disparities.”

7. Christensen et al., 11.

8. Christensen et al., 13.

9. Christensen et al., 13.

10. Christensen et al., 10.

11. Christensen et al., 11.

12. “DOD 2016 Demographics Report: Profile of the Military Community,” Office of the Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Military Community and Family Policy (2016); and “U.S. Navy Demographic Data Report,” Department of the Navy (2017). DoD does not report Hispanic/Latino populations as a racial minority, but if this demographic were incorporated, the 31.4 percent number would increase.

13. The Department of the Navy does not designate Hispanic/Latino as a racial minority in its demographic statistics. Hispanic/Latino personnel may select any racial category, but then have the option to select a Hispanic/Latino in the ethnic subcategory.

14. Specifically, African American, Native American, Asian, and Hispanic/Latino represent 13.3 percent, 1.3 percent, 5.9 percent, and 17.8 percent of the U.S. population, respectively. U.S. Census Bureau Quick Facts, 2018).

15. Government Accountability Office, “K-12 Education: Discipline Disparities for Black Students, Boys, and Students with Disabilities,” March 2018.

16. Government Accountability Office, “K-12 Education: Discipline Disparities for Black Students, Boys, and Students with Disabilities.”

17. Trachtenberg, “How University Title IX Enforcement and Other Discipline Processes (Probably) Discriminate.”

18. Christensen et al., “Racial Disparities,” 15.

19. Christensen et al., “Racial Disparities.”