Hurricane Harvey seemingly came out of nowhere in August 2017. The storm raised few concerns as it crossed through the Caribbean and neared the Gulf of Mexico, but over the next 48 hours it grew rapidly, catching emergency officials in Houston off guard and with not enough time to evacuate the city’s 5.6 million people.1

The storm made landfall as a Category 4 hurricane, and over the next week devastated the Gulf Coast of Texas. Houston, which received nearly four feet of rain, faced flooding unlike anything in its history. Citizens trapped in the state’s most populous city scrambled onto rooftops and clung to trees as floodwaters continued to rise.

Out of the devastation, the Coast Guard rescued 11,022 people and 1,384 pets. More than 2,000 servicemen and women worked tirelessly to keep more than 50 aircraft in the air and 75 flood teams operating around the clock.2 The Coast Guard is the world leader in search and rescue, and Hurricane Harvey will be remembered as one of its finest hours.

Harvey was historically significant for more than one reason. Not only was it the United States’ costliest natural disaster (with a $190 billion price tag), but it also has been coined “America’s First Social Media Storm.”3 With tens of thousands of individuals left trapped in the rising floodwaters, 911 operators became overwhelmed. Survivors were on hold for four, six, and even eight-plus hours, and thousands turned to social media as a last resort.

Social Media Emerges

Until Harvey, the Coast Guard could not “listen” to social media calls for help. This began to change as incident command leaders noticed the amount of emergency traffic originating from social media and quickly recognized the need to follow what was unfolding on Facebook and Twitter.

Urban search-and-rescue flood teams began using crowdsourced maps such as Rescue Map, which mapped calls for help in near-real-time.4 A Canadian software engineer helped launch another crisis map used in Coast Guard command centers.5

One of the most widely used information sources came from a joint effort with cadets from the Coast Guard Academy and volunteers from the Standby Task Force (SBTF) and Humanity Road (HR), digital humanitarian organizations that specialize in crisis mapping. Crisis mapping is the process of gathering “calls” from social media and mapping them so first responders can incorporate them into rescue operations. Both organizations are volunteer-driven, nonprofits that bring together geospatial systems and social media experts from around the world to support first responders and humanitarians.

During the response to Hurricane Harvey, volunteers from HR and SBTF collected calls for help while Coast Guard Academy cadets created maps for first responders to use in directing rescue efforts. The volunteers used hashtag and keyword searches to sift through millions of posts without using any intrusive software. By the conclusion of rescue operations, volunteers had collected data on more than 1,000 rescue cases involving more than 5,200 storm survivors.

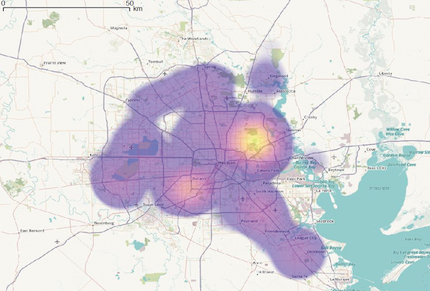

Heat map showing the density of search-and-rescue cases originating from social media during Hurricane Harvey in Houston, Texas.

The cadets’ maps quickly gained attention at all levels of the service. By the peak of rescue operations, they were being used by pilots and briefed to admirals. More specifically, the products and data were passed to Texas Task Force 1 (responsible for coordinating urban search and rescue in Houston), Coast Guard Eighth District Command Center, Coast Guard Geospatial Intelligence, and Coast Guard Sectors Corpus Christi and Galveston.

In the initial days following landfall, the service struggled to understand where the highest concentrations of survivors were located. Because of the sheer call volume, the focus shifted toward triaging the most urgent calls and responding to areas of highest survivor density. Pilots used heat maps generated from social media calls to guide those operations.

Crisis Mapping Outside the Coast Guard

Crisis mapping originated in the aftermath of the 2010 Haitian earthquake, and has gained international attention since. In 2012, the Digital Humanitarian Network (DHN) was established to bring together various digital humanitarian organizations to allow for easier coordination during response efforts.6 With partner organizations like SBTF and HR, the DHN has supported response efforts to dozens of disasters, including the Nepal earthquakes, Hurricane Maria, the disappearance of flight MH370, the Ebola outbreak, and Typhoon Yolanda.

Importantly for the Coast Guard, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) is a leader in working with digital humanitarian organizations. The agency partnered with Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team (HOT) and the Civil Air Patrol (CAP) to assess damage following disasters. The CAP has a fleet of 550 aircraft in every state and can be one of the first organizations activated after a disaster.7 HOT’s volunteers process imagery captured by the CAP through crowdsourcing. FEMA leveraged this partnership during Hurricane Maria to determine the status of Puerto Rico’s main roads while SBTF identified the status of the island’s hospitals.8 FEMA can act as a model for the Coast Guard as it establishes a process for monitoring social media.

In Dickinson, Texas, an air boat rescues hurricane victims who were able to use social media to alert responders of their situation.

Social Media in Future Responses

Hurricane Harvey demonstrated that Coast Guard response efforts benefit from social media. While not a replacement for 911 or VHF channel 16 distress calls, social media is an avenue through which information can be delivered to responders.

In the weeks after Harvey, Coast Guard Vice Admiral Sandra L. Stosz remarked at the AFCEA Homeland Security Conference that “no call goes unanswered by the Coast Guard.” Now the service needs to examine how to permanently and systematically monitor social media calls.9

To make this possible, four questions must be answered:

1. How will the Coast Guard collect information?

2. Who will be responsible for the information?

3. How will it be distributed throughout the Coast Guard?

4. How will the information be used?

Accessing and collecting the information is not difficult. There are several avenues through which the Coast Guard can acquire information from social media, including crowdsourcing and software systems. Disseminating the information creates a challenge, however. During Hurricane Harvey’s peak, survivors around Houston posted updates on social media more than 6.5 million times a day. The service will need to develop a process for collecting and wading through data of this volume, and then get the information to first responders and senior leaders immediately. First responders will need access to the data to coordinate individual rescues, and senior leaders will need it to allocate resources.

Finally, getting the information out in a timely manner is critical. Pilots in the air and flood teams should have access to near-real-time data to facilitate their response efforts. The Coast Guard will need to adopt a service-wide platform for sharing information. This could be software similar to GeoSuite, the common operational picture software used during Harvey, or it could be another platform. Regardless of the software, it is critical it be universally adopted across the service.

With these questions in mind, it is important to note that each disaster is different. Solutions must focus on maximizing flexibility and adaptability. For this reason, it will be important to incorporate a social media force in the ultimate solution.

This force could outline a process by which responders can escalate the Coast Guard’s presence on social media. On one end, the Coast Guard would set up a social media response team (SMRT) composed of public affairs and data analytics experts. This team would monitor social media for any major trends and direct survivors to contact rescuers through 911. For more severe disasters, the team could coordinate with the DHN and its partners, or direct survivors to post calls for help under a specific hashtag, making it easier to collect their calls quickly.

The force should be available during all Coast Guard responses. Small-scale responses might require a public information officer to occasionally post a message to Facebook or Twitter, and large-scale responses might require dozens of experts to monitor social media constantly.

The Coast Guard also should seek to establish a dispatch process based on social media posts. This process needs to stress the same flexibility and adaptability, but also ensure a post’s credibility.

By establishing contact with the survivor through social media, text, or phone call, the SMRT could confirm the post is authentic. In addition, it must be clear the survivor is in immediate danger. During Hurricane Harvey, it was common to see check-in requests with relatives that family members had not been able to contact. Unless it were obvious that there is an immediate risk to life, resources would not be dispatched. Finally, a social media expert needs to make a final judgment before assets are dispatched. This judgment call gives the SMRT a degree of autonomy over the monitoring process.

Pushing Through Concerns

One of the central issues holding back social media monitoring implementation is unanswered policy concerns. At the moment, the Coast Guard does not have the policy framework that will guide how the information is collected, packaged, and disseminated. Beyond this, there are questions of personal identifiable information (PII) sensitivity. If a survivor is posting information publicly in hopes of rescue, how does that change the sensitivity of their information? The definition of privacy in the 21st century is different than it was 30 years ago.

Bearing these questions and concerns in mind, the service should look for a commonsense approach. Concerns over handling PII, working with nongovernmental organizations, and privacy should not prevent the service from answering calls for help. Ignoring a social media post is the same as ignoring a 911 call. If the service is capable of flying into hurricanes, it is capable of addressing the issues that stand in the way of monitoring social media.

Throughout the Coast Guard’s history, crisis has bred innovation. Hurricane Harvey was no exception, and it was a milestone in Coast Guard disaster response. Not only did the Coast Guard save more than 11,000 lives, it also monitored social media for the first time. But unresolved questions and concerns remain, and the work toward systematically monitoring social media is just beginning. The Coast Guard must prioritize this tool for future disaster response.

Listen to a Proceedings Podcast interview with this author about this article below:

1. U.S. Department of Commerce, NOAA, National Weather Service., “Major Hurricane Harvey—August 25–29, 2017,” 15 December 2017.

2. “Summary of Coast Guard’s Hurricane Harvey Response Efforts,” Coast Guard News, 7 September 2017.

3. Maya Rhodan, “Hurricane Harvey: The U.S.’s First Social Media Storm,” Time Magazine, 30 August 2017.

4. Meg McIntyre, “Keene High Grad in Coast Guard Academy Helps Hurricane Harvey Response Efforts,” 5 September 2017.

5. Daniel Terdiman, “How a Hacker Helped the Coast Guard Rescue Victims of Hurricane Harvey,” Fast Company, 5 October 2017.

6. Patrick Meier, “How Crisis Mapping Saved Lives in Haiti,” National Geographic blog, 1 February 2013.

7. John Crowley, “Connecting Grassroots and Government for Disaster Response,” Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, October 2013.

8. “Standby Task Force Is Supporting FEMA in Response to Hurricane Maria,” Standby Task Force, 6 October 2017.

9. Nicole Ogrysko, “Recent Hurricanes Have the Coast Guard Rethinking Social Media’s Role in Rescue and Response,” Federal News Radio, 29 September 2017.