RUN THE STORM: A SAVAGE HURRICANE, A BRAVE CREW, AND THE WRECK OF THE SS EL FARO

George Michelsen Foy. New York: Scribner, 2018. 272 pp. Index. $26.

Reviewed by Captain Holly Harrison, U.S. Coast Guard

Of the many articles and several books written about the 1 October 2015 sinking of the SS El Faro with the loss of all 33 persons on board, this is one of the best. While a simplistic view of the El Faro’s demise is to fault the master’s choice to “Run the storm,” the truth is far more complicated. There are innumerable variables that combined and led to the tragic sinking of the El Faro; some occurred years earlier, others occurred days and even a few hours before the ship sank. These include corporate culture and the pressure to maintain schedules and profits, the modification and maintenance of the ship as she aged, loopholes in the regulation of older U.S. commercial vessels, the accuracy of weather reports and blind faith in them, overconfidence in the ship’s ability to handle heavy weather, failure to monitor and maintain the watertight integrity of the ship and properly secure cargo, choosing a trackline that provided few escape routes, an unwillingness to change the original plan when conditions changed, and the authority of a captain as the sole and ultimate decision maker on board the ship.

The author, George Michelsen Foy, conducted extensive research into the U.S. Coast Guard and National Transportation Safety Board hearings subsequent, which included thousands of pages of evidence, innumerable interviews, and more than 500 pages of transcripts from the ship’s voyage data recorder (VDR). Though the ship went down with no survivors, the 26 hours of bridge conversation and other data recovered from the ship’s VDR provide a rare and detailed look at what happened in the hours leading up to sinking. The crew’s own words allowed Foy to reconstruct what happened, giving readers a front row seat to the many seemingly trivial and disparate details that culminated in disaster.

Foy was careful not to make assumptions about gaps in the ship’s routine, particularly events that happened off the bridge that were not directly captured by the VDR. Instead, he offers reasonable interpretations of what may have been occurring based on additional interviews with former El Faro crew members, family members of the deceased crew, and experts in meteorology, engineering, navigation, and ship handling.

The challenge of telling the El Faro’s story is twofold: How to share myriad information with the reader and how to share it with seafarers and landlubbers alike. Foy did a masterful job weaving the relevant pieces of information into the story at just the right moments to provide context, and yet he kept the narrative flowing. His book stands apart because of his expertise as a mariner, which is evident in his accurate descriptions of merchant vessel operation, ship construction, shipboard culture, navigation, and marine weather, something that easily confuses non-mariners. While ensuring technical accuracy to maintain credibility with mariners, the author’s descriptions are such that someone who has little exposure to the open ocean or the commercial shipping industry can understand what happened and, most important, why it is relevant to the sinking.

There are many lessons throughout, and many missed opportunities where the path to disaster could have been avoided. Thousands of older ships in less than pristine condition sail the ocean every day and avoid disaster, as the El Faro did for many years . . . until 1 October 2015. Understanding the circumstances that converged to sink the El Faro and her crew can help other seafarers avoid the same fate.

Captain Harrison is a career cutterman and current Chair of the U.S. Naval Institute Editorial Board.

The Fighters: Americans in Combat in Afghanistan and Iraq

C. J. Chivers. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2018. 350 pp. Index. $28.

Reviewed by Captain David Allan Adams, U.S. Navy (Retired)

C. J. Chivers’ gritty and gripping The Fighters—an account of the exploits of six warriors as life carries them each from 11 September 2001 to combat—overpowers readers as they are skillfully immersed in the darkest human dimensions of the U.S. wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Chivers—a former Marine infantry officer, Gulf War combat veteran, and Pulitzer Prize–winning war correspondent—introduces us to Layne McDowell, a Navy strike-fighter pilot; Dustin “Doc” Kirby, a Navy corpsman serving with the Marines; Michael Slebodnik, an Army chief warrant officer and scout helicopter pilot; Robert Soto, an Army enlisted infantryman; Jarrod Neff, a Marine infantry platoon commander; and Leo Kryszewski, a special forces senior enlisted operator. Reminiscent of great fiction writers such as Twain, Steinbeck, and Hemingway, Chivers lets readers get to know these men. You are swept briskly through their lives until you find yourself center stage with them as they become embroiled in modern combat and face its aftermath. The beauty with which Chivers executes his craft cannot be overstated.

It is obvious why the The Fighters has garnered much-deserved praise from other reviewers. But the paucity of criticism is troubling as this book is not without its failings. Chivers’ research is so rigorous, his prose is so powerful, and his storytelling so genuine that it is easy to miss how he hijacks the lives of these heroes to drive what ultimately is an unbalanced narrative. He paints these warrior as victims of “bad decisions” with the aim that “their labors—what they gave in good faith—might be fully understood, even when squandered by those who sent them.”

Just as Clint Eastwood was criticized for the movie American Sniper’s use of Navy SEAL Chris Kyle’s life to portray an overly positive perspective on the invasion of Iraq and to promote unvarnished patriotism, Chivers leverages the lives of these heroes and risks exaggerating the human consequences of “the misjudgments of political and military figures above them.” His drawn-out portrayal of former President George W. Bush’s meeting with the severely wounded Doc Kirby and his family appears overwritten to drive home the book’s main point.

Chivers aims to understand the impact of serving in “wars that ran far past the pursuit of justice, and ultimately didn’t succeed.” While there may be some added psychological toll associated with participation in wars with ambiguous outcomes, the author fails to argue convincingly that if the wars had been spectacular successes the human consequences would have been less dire. Would the suffering of the severely wounded Kirby or the family’s mourning of Slebodnik—who was killed in action on 11 September 2008— somehow have been lessoned by clear successes?

The book ultimately ponders “How many lives have these wars wrecked?” But all wars—win, lose, or draw—wreck lives. Those lives it does not wreck (the vast majority), it changes in both positive and negative ways. Too many people are unwilling to consider that military service—especially in combat and despite the horrors of war—can strengthen human character. As Secretary of Defense General James Mattis reminds us, “There is also something called post-traumatic growth where you come out of a situation like that and you actually feel kinder toward your fellow man and fellow woman.” The reader should contemplate Chivers’ question but should be wary of the loaded answer to which his brilliant storytelling can lead.

On balance, The Fighters is a must read for those who study the human dimensions of war. There is possibly no better written history of service in Iraq and Afghanistan as told through a compelling account of combat and its individual consequences on these six heroes. It could have been even better if it were more balanced in the selection of cases and more honest in its analysis.

Captain Adams retired in 2016 and is a contributing editor to Proceedings. He commanded the Khost Joint Provincial Reconstruction Team, the USS Santa Fe (SSN-763), and the USS Georgia (SSGN-729 Blue).

Rampage: MacArthur, Yamashita, and the Battle of Manila

James M. Scott. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2018. 640 pp. Maps. Photos. Notes. Biblio. Index. $32.95.

Reviewed by Richard Frank

This is an excellent but wrenchingly graphic account of one of the least commemorated massacres in World War II. The exact toll remains uncertain, but it probably exceeded 60,000 lives, overwhelmingly Filipino.

In January 1942 when the Japanese seized Manila (“The Pearl of the Orient”), it was a showcase with grand buildings, boulevards, and parks. The city was scarcely damaged as the senior U.S. commander, General Douglas MacArthur declared Manila an “Open City” under international law to preclude it from becoming a battleground. When MacArthur “returned” in 1945, he expected the Japanese to have likewise declared Manila an "Open City," and he envisioned a grandiose victory parade through its streets.

Rear Admiral Sanji Iwabuchi had other plans. He led almost 17,000 Japanese, mostly sailors, in a fight literally to death that left Manila, next to Warsaw, the most devastated Allied capital city in the war. Scott has dug very deep into the U.S. and Philippine records of the battle and uses them deftly. No such wealth of records exists for the Japanese side, just a scattering of captured documents and interrogations of the very few POWs.

The horrifying suffering of Manila’s citizens far outstripped even the appalling physical devastation. Facing their own imminent deaths, the Japanese unleashed a murderous rage, slaughtering Filipino males as young as ten as suspected guerrillas or their supporters. But the Japanese also massacred the general population of all ages and both genders, commonly using swords (typically for beheading), bayonets, grenades, bullets, and even burning alive trapped victims. Scott wields the vivid testimony of the rare survivors to portray the full horrors of the events. Many hundreds of women, some mere girls, were raped, frequently mutilated, and then killed.

Scott addresses the two major controversies that linger over the battle. The first involved U.S. tactics to defeat Iwabuchi. MacArthur forbade the use of aerial bombardment because of its inherent inaccuracy. His subordinates substituted the use of massive artillery firepower. This undoubtedly added substantially to the toll of Filipino dead, though it seems far more probable that significantly more Filipinos perished at Japanese hands.

The second issue involves the culpability of the overall Japanese commander in the Philippines, General Tomoyuki Yamashita. A military tribunal set up by MacArthur tried Yamashita for the destruction of Manila and many of its citizens, though the general was not in the city. Besides the trial’s manifest procedural injustices, no “smoking gun” evidence emerged that Yamashita himself had ordered or condoned Iwabuchi’s actions.

The U.S. Supreme Court denied an appeal on Yamashita’s behalf and he was executed ignominiously by hanging. The trial did create a still ambivalent principal concerning command responsibility of a senior officer for such egregious conduct of subordinates. In terms of simple justice, after Yamashita’s capture of Singapore in 1942, troops indisputably under his command slaughtered masses of Chinese civilians clearly on orders from above. Absent the Manila trial, Yamashita almost certainly would have been executed for the mass murders in Singapore.

Thanks primarily to books and film, German atrocities in World War II are well known, but the horrendous slaughters of probably 17 million or more mostly Asian noncombatants by Japan remains little remembered. This account will go a long way toward filling that void.

Mr. Frank is an internationally recognized scholar of the Asia-Pacific war. His next work is Tower of Skulls, volume one of a trilogy on the Asia-Pacific war, for publication by Norton, fall 2019.

The Perfect Weapon: War, Sabotage, and Fear in the Cyber Age

David E. Sanger. New York: Crown, 2018. 354 pp. Notes. Index.

Reviewed by Captain Ramberto “Rambo” Torruella, U.S. Navy

“Warfare was about bullets and oil until now . . . warfare in the twenty-first century is about information.” – Comment attributed to Kim Jong-Il to his top commanders in 2003.

In the summer of 2010, cybersecurity researchers at Symantec were investigating an interesting, new computer worm found circulating in the wild. It was sophisticated, almost exquisite in its design. It was big, larger by far than most other worms. It was practically flawless, having very few bugs; unusual in any piece of malware. It was expensive to engineer, exploiting four different zero-day vulnerabilities—a single zero-day vulnerability costs in the hundreds of thousands of dollars on the hackers' black market. Most telling, it was very specifically targeted, attacking only Siemens Programmable Logic Controllers. In the minds of the researchers, this worm could not be the work of a single individual hacker or group of hacktivists. In the eyes of the world, it became clear that only one nation had that kind of cyber firepower: the United States. Its malware was made for one specific target, the uranium enrichment facilities in Natanz, Iran.

Thus begins the history of the war in cyberspace we are living in today. David Sanger, a well-connected reporter from the New York Times, broke the story of Operation Olympic Games, better known as the Stuxnet Attack on the Iranian nuclear centrifuges. He uses his highly placed connections to delve deep into the world of great power competition in cyberspace in his new book, The Perfect Weapon: War Sabotage, and Fear in the Cyber Age. It reads like a thriller spy novel, except the stories are true, which makes the book more terrifying.

Perfect Weapon documents the United States’ original sin in cyberspace—the release of Stuxnet on Iran—and details the tit-for-tat responses from other cyber powers: Russia’s hack of the Pentagon’s secret network, Iran’s distributed denial-of-service attack on U.S. banks, North Korea’s hack of Sony Entertainment, and so on. Sanger relates how each responds to the other’s maneuvers in cyberspace—the United States by hardening its networks; Russia, China, Iran, and North Korea by seeking to further their asymmetric advantage, to use cyberspace as an arena where they can level the playing field against U.S. military might.

Caught in the middle are allies and industry targets who suffer through cyberattacks as pawns in the game of cyberspace dominance. Sanger shows the political, military, and economic impacts of actual hacks, moves made by governments and industry to counter moves and protect against future attacks, and the counter to the counter to the counter, all told at a breathtaking pace.

But this is more than just a real-life cyber drama; it also is a cautionary tale of the policy of information power. It shows how the United States remains ever so cautious about wielding its cyber might, first in an effort to preserve its diminishing edge in cyberspace, but mostly with the knowledge that its weapons could be used against it. It shows how both U.S. allies and adversaries are much less cautious in wielding the cyber sword, especially if an effect from a cyberspace weapon yields the same result as an economic or military effect without the loss of life.

It plays against U.S. weakness as a culture—is shutting down the banking sector the same as shooting down a plane or sinking a ship? Is the United States ready to reduce a nation to ruins for stolen credit cards or identities? When is an influenced election an act of war? Perfect Weapon documents these policy debates in the halls of the Pentagon, Congress, and across the diplomatic sphere; all with the special access of a reporter who speaks to spies, diplomats, tech gurus, and heads of state. His access is unprecedented.

This book at turns was both fascinating in its detail and access and terrifying in its implications. It shows that at the highest levels of government, the United States sees its cyberspace weapons as special, akin to nuclear weapons, used only in break-glass-in-case-of-emergency scenarios. U.S. adversaries see cyberspace weapons as an inexpensive and easy to use tool in the diplomatic, information, military, and economic (DIME) toolbox. They may not be eating our lunch just yet, but it is clear that we may be operating at a disadvantage.

Captain Torruella is the Director of Networks and Communications and Chief Information Officer for Commander Naval Forces Europe, Africa, and U.S. Sixth Fleet. He is a 1992 graduate of the Naval Academy and a 2009 graduate of the Industrial College of the Armed Forces.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY BOOKS

By Captain William Bray, U.S. Navy (Retired)

Intervention! The Americans in Haiti, 1915-1934

Commander Richard L. Schreadley, U.S. Navy (Retired). Charleston, SC: Evening Post Books, 2017. 232 pp. Illus. Index. $19.99.

Before its long and tragic intervention in Vietnam, the United States embarked on an even longer extraterritorial intervention. While the 19-year intervention in Haiti was not as socially divisive or costly in terms of loss of life, it bore similarities in origin and execution to Vietnam that should have served as potent warnings to policy makers of the Eisenhower, Kennedy, and Johnson administrations. Through careful research, to include accessing an unpublished manuscript of Naval Institute forebear Edward Beach Sr., Commander Schreadley does a great service to both the comparison and this fascinating chapter in U.S. foreign policy. Part one of two, or approximately a fourth of the book, is a tightly wrought history of Haiti itself, perfectly setting the context to better understand the U.S. phase. The remainder takes the reader through the intervention period, all the good and the bad of it (and some of the bad is difficult to read), in an engrossing exposé.

Four Guardians: A Principled Agent View of American Civil-Military Relations

Jeffrey W. Donnithorne. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2018. 235 pp. Illus. Index. $49.95.

Although the title is somewhat obscure, and the writing borders on the dryly academic, Jeffrey Donnithorne succeeds in delivering an interesting, thoughtful, and thoroughly unique analysis of U.S. civil-military relations. The principled agent theory (an agent is appropriately empowered, respected, and acculturated to act according to a higher principle, like civilian control of the military) is employed as a framework to examine how the distinct histories and cultures of the four U.S. military services have supported and reinforced the United States’ bedrock tradition of civilian control of the military. Since the 1980s and the era of jointness, service culture often has been cast as a restraint on progress, the chief culprit of costly interservice battles. Donnithorne examines each culture in a more positive light and demonstrates in two notable case studies how service culture helped accomplish civilian imperatives regarding larger, transformative joint objectives.

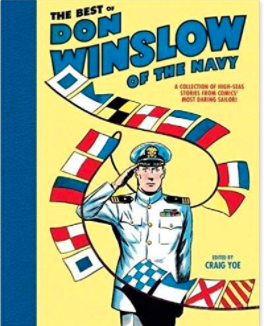

Craig Yoe, ed. Annapolis, MD: Dead Reckoning Press, 2018. Illus. $29.95.

Lieutenant Commander Don Winslow is a comic book action figure, the creation of Frank V. Martinek, himself a former naval officer from the World War I era (Martinek was a cryptographer in the early years of that specialty). After leaving active service in 1921, Martinek remained in the Naval Reserve and in the 1930s was chairman of publicity for the Navy League of the United States. He got the idea for a Navy comic strip from the famous Popeye series and first introduced Winslow in 1934 as a way to help the Navy improve recruiting from the landlocked Midwest during the interwar years. Like Martinek, the character Winslow serves in intelligence, rich fodder for all manner of adventure. Craig Yoe, formerly a creative director for Disney and Jim Henson’s Muppets, brings more than 20 of the best Don Winslow strips back to life, all digitally restored. In addition, he contributes a wonderful opening essay on the history of the Don Winslow strip. This rare piece of history is a pleasure to read, and it undoubtedly captured the imaginations of countless young American men.

Lieutenant Commander Don Winslow is a comic book action figure, the creation of Frank V. Martinek, himself a former naval officer from the World War I era (Martinek was a cryptographer in the early years of that specialty). After leaving active service in 1921, Martinek remained in the Naval Reserve and in the 1930s was chairman of publicity for the Navy League of the United States. He got the idea for a Navy comic strip from the famous Popeye series and first introduced Winslow in 1934 as a way to help the Navy improve recruiting from the landlocked Midwest during the interwar years. Like Martinek, the character Winslow serves in intelligence, rich fodder for all manner of adventure. Craig Yoe, formerly a creative director for Disney and Jim Henson’s Muppets, brings more than 20 of the best Don Winslow strips back to life, all digitally restored. In addition, he contributes a wonderful opening essay on the history of the Don Winslow strip. This rare piece of history is a pleasure to read, and it undoubtedly captured the imaginations of countless young American men.

Cashing in on Cyber-Power: How Interdependent Actors Seek Economic Outcomes in a Digital World

Mark T. Peters II. Lincoln, NE: The Potomac Press, 2018. 198 pp. Appendix. Biblio. Index. $27.95.

Cashing in on Cyber-Power is adapted from a doctoral dissertation, and as such it is heavy on both the theoretical and language that often runs to the abstruse. Readers should be ready to tangle with sentences like this one: “An individual emphasis on interdependent characteristics and their cyberpower applications advances the overall understanding of how a cyber-enabled economic frame emerges and shapes multiple channels, hierarchical formlessness, and military de-emphasis.” This does not make for easy or enjoyable reading, particularly for those without a deep technical background in the cyber realm. But it is a valuable contribution to the growing field of cyber literature. And for a national security audience concerned primarily with military applications of cyberpower, Mark Peters’ impressive effort helps expand thinking about competition in the global cyber commons. Researchers, cyber policymakers, and even cyber warfare practitioners will especially benefit by reading the case studies in the sixth of seven chapters.

Captain Bray served as a naval intelligence officer for 28 years before retiring in 2016. He joined the Naval Institute staff in August 2018.