Brazil

Admiral Eduardo Bacellar Leal Ferreira,

Commander Brazilian Navy

Economic growth, political stability, and the development of a democratic society have made Brazil an important global player—and brought international responsibilities—over the past several decades enabling it to play a relevant role in seeking world peace, focused on the South Atlantic. The Brazilian Navy (BN) has been taking a significant part, preparing and applying sea power to support international relationships and interests at sea. Brazilian legislation simultaneously establishes missions to defend national sovereignty at sea and defines the commander of the navy as the Brazilian Maritime Authority. The BN has became a dual-purpose force, able to act in the military field employing sea power to perform sea control, sea denial, power projection, and deterrence. It also fulfills constabulary tasks, such as maritime patrol, shipping control, humanitarian assistance, search and rescue (SAR), and maritime traffic safety. A modern, balanced, and reliable sea power, capable of building partnerships contributes to Brazil’s efforts to support global peace and regional stability.

Brazilian Navy soft power tasks include peacekeeping operations, combined exercises, and naval cooperation. From 2004 to 2017, the BN participated in the U.N. Stabilization Mission in Haiti (UNSTAMIH). In 2011, it took over the U.N. Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL) Maritime Task Force leadership, deploying a flagship in the Eastern Mediterranean Sea. BN participation in exercises such as UNITAS, Atlasur, Fraterno, and Ibsamar has established interoperability and strengthened friendship ties with several other navies. Regarding naval cooperation, its importance was highlighted during the 2014 World Soccer Championship and the 2016 Olympic Games, in which we shared information with many nations. One of the lessons learned was the importance of increasing our partnership, cooperation, and interoperability. The BN also has been assisting in the development of several West African naval forces, including the Namibian Navy and the Cape Verde and St. Tome and Principe coast guards. Naval cooperation with African countries also has been accomplished by providing training courses in Brazil to naval personnel from Angola, Mozambique, Nigeria, and Senegal. Brazilian Navy offshore patrol vessels have been operating with several other countries’ vessels during Obangame Express exercises in the Gulf of Guinea.

On a daily basis, the Brazilian Navy proves its ability to work hand-in-hand at all levels with its partners, fostering international trust and consolidating its role as a major player for keeping peace and regional stability.

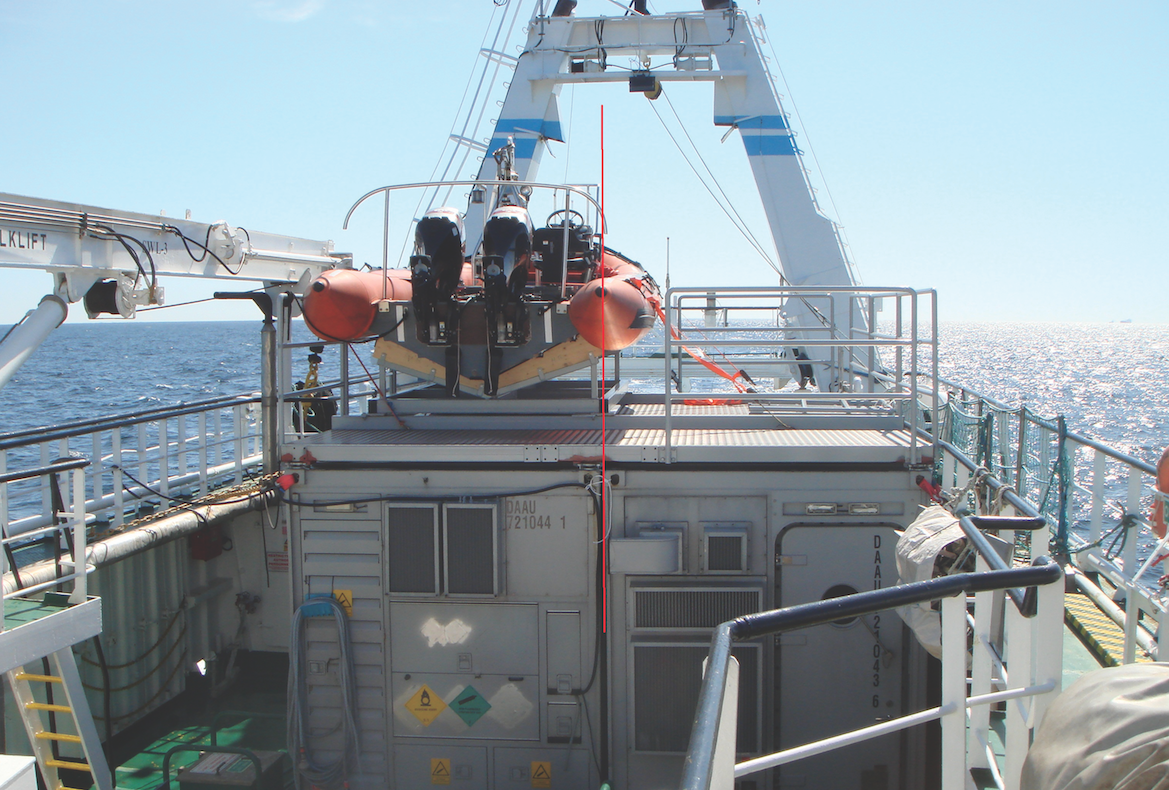

The Danish Navy containerized its mine countermeasures (MCM) command modules so that they could be installed on almost any ship, allowing improved mobility and flexibility.

Denmark

Rear Admiral Torben Mikkelsen,

Chief of Danish Naval Staff

Maintaining freedom of the seas and access to the global maritime commons is a core business for the Royal Danish Navy (RDN). One example from the RDN “toolbox” is the approach to mine countermeasure (MCM) operations, which requires naval partnerships, cooperation, and interoperability to ensure a modern and flexible capability.

A few years ago, the RDN ended the use of dedicated MCM units. To maintain the capability, we had to rethink the MCM concept and find a cost efficient, yet effective alternative. The solution was a modular, containerized, and remotely operated MCM system reusing relevant systems from decommissioned ships. The command-and-control systems were updated, and surface drones and the underwater robots were reconfigured to create a more flexible system to conduct the full spectrum of MCM operations.

Today’s command modules are containerized versions of the combat information centers from previous MCM vessels. The entire MCM system can be operated from the command modules, which can be positioned ashore or embarked on board RDN warships, other allied ships, or even on merchant ships.

The main sensor of the Danish MCM system is a side scan sonar, towed by a surface drone, conducting mine detection and classification. The next step—mine identification and disposal—is conducted by means of a camera-fitted mine disposal vehicle or by MCM divers. The entire modular system is operated by a crew of 32.

The system has been tested and proven on board various platforms—military and civilian—and has performed extremely well. Although it is a “first generation” modular system, the potential for further development is obvious, and we intend to continue upgrading.

Based on our expertise, Denmark has taken the lead on a smart defense project that deals with mission modules for MCM operations. The aim is to define possibilities for the use of mission modules to operate from a variety of platforms to perform MCM tasks. To achieve this, a multinational specialist team was formed to examine the introduction of mission modules. The result may be used for follow-on investments and cooperation in developing, acquiring, and maintaining such capabilities. This includes the principles of “pooling and sharing” with other allied navies.

The Danish MCM system has been and will continue to be deployed with Standing NATO Mine Countermeasure Group One (SNMCMG1), and it has helped to increase NATO MCM interoperability, develop procedures, and enhance doctrine and tactics among the various manned and unmanned MCM systems available within NATO. Denmark will take command of SNMCMG1 in 2019. The Danish contribution will consist of a flagship, with the commander and staff embarked, and periodically will include the modular MCM system deployed on a unit of opportunity.

The Swedish and Finnish navies have formed a permanent combined naval task group to increase each other's strength. Here, the Swedish Visby-class corvette Harnosand and the Finnish Rauma-class missile patrol craft Rauma (right) operate together.

Finland

Vice Admiral Veijo Taipalus,

Commander of the Finnish Navy

The Finnish Navy cooperates on the deepest level with the Swedish Navy. The Swedish and Finnish navies have been engaged since the late 1990s in bilateral exercises, exchanges, research, development, and acquisition programs, and operational activities. The main objectives of our cooperation are to use resources cost-effectively and to operate efficiently in a number of maritime areas including: maintaining and developing interoperability and operational capabilities, enhancing cooperation in exercises, building common opportunities for education and training, enhancing sea surveillance under the Sea Surveillance Cooperation FinlandSweden-program, using common base infrastructure, and developing the capability to transfer operational control of units between the two navies.

In today´s and tomorrow´s operational environment there is a need for maritime forces that can operate throughout the full spectrum of conflict. This means forces and capabilities that have high readiness, good endurance, and high interoperability. They must be able to operate under combined, joint, and interagency command-and-control structures and bring to bear their warfighting skills. A core strength and edge that maritime forces provide is conflict prevention through early response and crisis management. The combined Swedish-Finnish Naval Task Group (SFNTG) brings those capabilities through smart, cost-effective means for both nations.

The SFNTG consists of a combined directing staff and operational task units that include surface warfare, mine countermeasures, amphibious warfare, and logistics assets from both countries. The command structure and composition of assets can vary and are based on situational requirements. The SFNTG also can be a regional contribution as a tool for crisis prevention and crisis management in our own waters, in the Baltic region, or outside the area. The task group achieved initial operational capability in late 2017. In the near future, additional steps will build toward full operational capability and force integration in 2023.

The SFNTG has deepened each nation’s mutual understanding for national defense. Finland and Sweden learn from each other and develop national defense activities based on this cooperation. In addition, our bilateral cooperation is built as much as possible on NATO and European Union standards to avoid duplication.

France

Admiral Christophe Prazuck,

Chief of the French Naval Staff

The growth in naval shipbuilding in almost every part of the world should not lure us into the belief that tonnage is the sole metric by which to gauge navies. In a rapidly evolving technological context, raw capability remains as important as ever. However, as we mark the 100th anniversary of World War I, history reminds us that capability must be considered against other decisive factors, such as the quality of one’s human resources, the breadth of one’s partnerships, and the resilience of the industrial base.

The French Navy is proud to operate a nuclear-powered aircraft carrier, nuclear-powered submarines, amphibious ships, ocean-patrol vessels, special forces, and cruise missiles—all within a compact force of about 80 ships and 40,000 sailors. Our forces deploy globally on a routine basis, not only to support and protect overseas territories and the second largest exclusive economic zone (EEZ) in the world, but also to train and operate with a wide network of allies, from our natural allies in Europe and across the Atlantic, to those as far away as South America, Africa, the Northern Indian Ocean, and the Asia-Pacific.

The French Navy adheres to the principle of “National Strategic Autonomy,” spearheaded by a fully independent, continuously at-sea strategic ballistic missile submarine deterrent and a carrier strike group. We also are engaged fully in bilateral, trilateral, and multilateral activities with the United Nations, European Union, NATO, and Combined Maritime Forces (CTF-151)—in operations as well as through industrial cooperation. More than half of the French Navy’s frigates, missiles, and helicopters, for example, were built in collaboration with an international partner.

We would not be able to achieve such a Navy without a highly skilled workforce, empowered through an efficient training process and devolved mission command to take responsibility and act at the lowest possible level. “Every sailor counts” has been our principle and, so far, the French Navy’s human resource system has avoided the recruitment and retention difficulties encountered by many armies and navies. Our sailors are fantastic ambassadors throughout the world, and their professionalism and enthusiasm lend credibility to our partnership and development programs.

French Navy ships, aircraft, and equipment are custom made and backed by an industry that is highly advanced. Our ships, aircraft, and submarines are equipped with many diverse systems to maintain all the capabilities needed in such a small but heavily worked fleet. The combined effect of this equipment and manpower package allows the French Navy to be present and active on a global scale. Credible presence promotes partnership and cooperation of which we are very proud. Our work with partners around the world, and the respect our capabilities and operations have earned, ensure the French Navy is a force for good in upholding the rules-based international system.

Germany

Vice Admiral Andreas Krause,Inspector of the German Navy

Germany’s spheres of interests in the maritime domain range from the northern flank of Europe via the Atlantic Ocean down to the Mediterranean and extend into the Indo-Pacific region. Our operational requirements range from constabulary-like maritime security tasks up to multidimensional warfare. Thus, the German Navy will focus on high-end capabilities to be prepared for the entire range of potential tasks with the flexibility and sustainability needed.

Within the next 20 years, the German Navy will replace, modernize, or upgrade almost its entire current order of battle. Starting later this year the first of four new F125 Baden-Wurttemberg-class frigates, with a multiple crew concept and significantly enhanced sustainability, will be added to the fleet. Further future capability enhancements will include the second batch of five K130 Braunschweig-class corvettes (bringing the total to ten); six new multirole combat ships; the replacement of the maritime helicopter fleet; new manned and unmanned mine countermeasure units; the ballistic missile defense capability upgrade of our Type 124 Sachsen-class antiair warfare frigates; and the modernization of eight maritime patrol aircraft.

Partnership, cooperation, and interoperability always have been driving factors for the German Navy and will continue to be. Whether within the United Nations, the European Union (EU), NATO, multilaterally or bilaterally, the German Navy stands behind the principle of addressing the challenges of our time in common endeavors. The German Navy has been contributing to NATO’s Standing Naval Forces on an enduring basis for decades and is contributing assets to EU Operations Sophia and Atalanta as well as the U.N. Operation UNIFIL in the Mediterranean since their beginnings. The Type 124 frigate Hessen will deploy as part of the USS Harry S. Truman (CVN-75) carrier strike group in the first half of 2018.

With an initial operational capability in 2019, the German Navy will stand up the multinational Baltic maritime component command in Rostock, Germany, which will improve NATO’s maritime command-and-control capabilities significantly.

The German Navy has close ties with the British Royal Navy in naval warfare training, the Royal Dutch Navy in the amphibious domain, and unprecedented cooperation with the Royal Norwegian Navy in the procurement of commonly developed, identical conventional submarines.

All these naval capabilities and operations are only possible thanks to the enormous efforts by the men and women serving in the Germany Navy. Their spirit, passion, innovative strength and constant will to improve have secured these achievements, and I consider them our most important and unique capability.

Greece

Vice Admiral Nicolaos Tsounis,Chief of the Hellenic Navy

The Mediterranean Sea holds great geostrategic and economic importance as a primary shipping artery and an energy hub for Europe and Africa. It connects with the Atlantic, the Black Sea, and the Red Sea. Greece is a seafaring nation, and the Hellenic Navy continues the nation’s long-standing naval history and tradition.

Guarding against modern threats at sea, the Hellenic Navy maintains constant naval presence, as well as land-based infrastructure, in the region. These forces are in close proximity to critical choke points, providing accurate surveillance and operational and warfighting capabilities. Moreover, because of its proximity to areas of unrest, the Hellenic Navy maintains high operational readiness. In that context, our antisubmarine warfare capabilities in littoral waters and open seas have increased significantly in recent years. Our submarine flotilla—which comprises 11 diesel submarines including six Type 209s, one modernized Type 209 with air independent propulsion (AIP), and four state-of-the-art AIP Type 214s—is the tip of the spear for the Hellenic Fleet. Our submarines are capable of effective strike operations against naval forces, as well as executing a wide variety of supporting operations in a national, allied, and international context.

Apart from our operational capabilities, it is important that we enhance, deepen, and broaden our work with allies and partners. Therefore, we strongly support a broad interagency and international approach to law enforcement against criminal activities at sea. To that end, we have developed civil-military cooperation with various national maritime institutions, agencies, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), police, and the coastguard. International cooperative efforts such as the European Union’s Agency for the Management of Operational Cooperation at the External Borders of Member States (FRONTEX) and NATO’s Aegean activity—coupled with the work of Greek national agencies and NGOs—have helped to tackle the challenges of illegal immigration across our eastern sea borders.

Moreover, we keep close and productive relations with allies and partners high on our agenda. The framework of cooperation may differ from time to time and according to mission requirements, but the goal always remains the same. At this time, naval cooperation among the Adriatic and Ionian seas navies (Greece, Italy, Albania, Montenegro, Croatia, and Slovenia) is gaining momentum.

In the eastern Mediterranean, the Hellenic Navy has assumed a “bridging” role among the navies in the area based on close traditional relations between Greece and the Arab world and newly developed cooperation with the Israeli Navy.

The Hellenic Navy actively promotes interoperability, not only with regard to equipment, but also in the mind-set of personnel. Capacity building is a cornerstone of these efforts. The Hellenic Navy has developed a comprehensive toolbox focusing on education and training that includes education, niche personnel training, operational training at the unit level, evaluation, and operations and exercises.

Our primary operational training tool is the NATO maritime interdiction operational training center in Souda Bay, Crete. This multinational training center provides specialized training on maritime interdiction operations—including boarding team operations and tactics—to allied and partner navies and security services.

Finally, partner navies can benefit from the Hellenic Navy’s accumulated experience by participating in various operational training activities, as we conduct several invitational exercises each year (e.g., Ariande, Naias, Niriis, and Aegean Shield). The goal of these exercises is to improve interoperability and fighting capabilities in all fields of modern maritime warfare.

Italy

Admiral Valter Girardelli,

Chief of the Italian Navy

The global scenario continues to be turbulent, with a host of interrelated factors that generate crises and tensions of rising intensity and complexity, well beyond local and continental boundaries. Against this background, freedom of the seas and access to the global maritime commons are hampered by hybrid, asymmetric, and conventional threats, thereby requiring navies to be prepared for the full spectrum of maritime operations—from low- to high-end.

The maritime areas of strategic interest for Italy stretch beyond the Mediterranean region where traditional roles and modern security tasks coexist. The Italian Navy is committed to continuous participation in EU Operations Atalanta and Sophia and NATO’s Sea Guardian, while at the same time conducting our national operation called Mare Sicuro (Secure Seas).

The complexity of today’s global commons, characterized by strong economic and security interconnections among different regions of the globe, calls for innovative and federated approaches toward cooperative deterrence and responses at sea.

In this sense, the Italian Navy has gained wide experience in developing cooperative initiatives, through an inclusive attitude in naval partnerships and international relations. We use a stairstep, building-block approach aimed at a shared and common ownership. Our main effort is concentrated in the Mediterranean basin, with some valuable multilateral initiatives such as the Adriatic-Ionian Initiative (ADRION). These efforts enable regional navies to cope with common challenges through the “On Call Maritime Force” and the maritime dimension of the “5+5 Defence” Initiative. The Italian Navy also conducts bilateral engagements with up to 40 different countries, and supports fellow navies such as those of Algeria, Lebanon, Libya, and Qatar with tailored activities of maritime capacity building to increase their own skills and readiness.

In the area of maritime situational awareness, the transregional maritime network—aimed at sharing unclassified information related to merchant shipping—has grown to a membership of 36 navies, with an increasing interest for others to join.

Cooperation activities need to be complemented and further reinforced by naval presence: the early 2017 deployment of the ITS Carabiniere—a FREMM-type frigate—to Australia and South East Asia provided the opportunity to engage new partners in a region whose dynamics are strongly interconnected with those of the Mediterranean. In the summer of 2017, the oceanographic research vessel ITS Alliance exposed the Italian Navy to new fields of cooperation. The participation of the ITS Rizzo in exercise Formidable Shield aimed at developing interoperability in the ballistic missile defense context.

The effectiveness of such a multidomain and multidisciplinary approach has been further testified by the success of the XI Venice Regional Seapower Symposium, where, last October, representatives of 47 navies and 11 international organizations gathered for three days to discuss and share views on issues of mutual interest strictly correlated to the quest for freedom of access to global commons. They all agreed on the importance of considering maritime security as a combination of security operations, situational awareness, and capacity building, thereby recognizing the validity of the Italian Navy approach.

India

Admiral Sunil Lanba,

Chief of the Indian Naval Staff

Maintaining freedom of the seas and access to global maritime commons have assumed renewed significance in recent times as a result of the increasing traditional and nontraditional challenges in the maritime domain. Nations around the world are reawakening to the criticality of the oceans and are investing in capabilities to harvest resources from seas and oceans. The rising demand for ocean-based resources has prompted some nations to explore avenues far from their home waters, which also has given rise to renewed territorial assertiveness and nationalistic ambitions in some parts. At the same time, maritime piracy, use of the seas by terrorists, human and drug trafficking, the vagaries of climate change, and illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing also have emerged as issues of concern.

India’s maritime aspirations have been outlined in our Prime Minister’s vision of “SAGAR” (the Hindi word for “oceans”) which is an acronym for “Security and Growth for All in the Region.” The Indian Navy assumes the role of a “net security provider” in India’s areas of maritime interest. We are cognizant that a secure environment cannot be achieved by the efforts of a single nation. Accordingly, maritime cooperation is an important facet of our security endeavors in the region.

The Indian Navy maintains sustained presence across the Indo-Pacific region through mission-based deployments of its units. Our ships and aircraft are deployed in the strategically important spaces and near important choke points in the Indian Ocean. These efforts are strengthened with coordinated/joint patrols, bilateral/multilateral exercises, and surveillance of friendly nations’ exclusive economic zones (EEZs), which also enhances interoperability at sea. In addition, we engage several regional navies through a wide range of capacity-building and capability-enhancement initiatives. These include provisioning of necessary military hardware, materiel and maintenance support, operational exposure, training, and hydrographic assistance. Comprehensive information sharing mechanisms also have been established with several navies, and these provide a high degree of shared maritime domain awareness.

All these endeavors are underpinned by a strong sense of respect for the sovereignty of partner nations and aim to instil a sense of local ownership so that all coastal nations contribute willingly and enthusiastically to maritime security. All these engagements are symbolic of our national values and beliefs. It is beyond doubt that ensuring freedom of the seas, adhering to international norms, and interacting on the principles of mutual respect are essential for peace and economic growth in the world at large and its maritime dimension in particular.

In October 2017, the Japanese Maritime Self-Defense Force, Indian Navy, and U.S. Navy conducted Exercise Malabar in the Bay of Bengal. The USS Nimitz (left), INS Vikramaditya (center), and the JMSDF Izumo (right) participated.

Japan

Admiral Yutaka Murakawa

Chief of Maritime Staff

Open and stable seas are indispensable for the peace and prosperity of Japan and the world. The Japanese 2013 National Security Strategy introduced the concept of a “Proactive Contribution to Peace,” through which Japan should contribute to the stability and prosperity of the Asia-Pacific region and the world. Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has announced a “Free and Open Indo-Pacific Strategy,” noting in a speech that “Japan bears the responsibility of fostering the confluence of the Pacific and Indian Oceans and of Asia and Africa into a place that values freedom, the rule of law, and the market economy, free from force or coercion, and making it prosperous.” The Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force (JMSDF) is proud to play the role of a key force in carrying out these policies of the government of Japan.

In 2017, the JMSDF deployed the DDH Izumo and its surface action group to the South China Sea and the Indian Ocean, engaging with navies throughout the region. This was just one example of JMSDF contributions to national policy. Other contributions include counterpiracy operations in the Gulf of Aden, logistic support for antiterrorism maritime interdiction operations in the Indian Ocean, and capacity building with partner navies. These activities are military operations other than war, but the basis for such operations is the JMSDF’s capacity for high-end warfighting, which we have developed over a long time.

Our best example of naval cooperation is the successful multinational counter-piracy operations in the Gulf of Aden. The JMSDF contributes its high-capacity, mission-capable maritime patrol and reconnaissance (MPRA) force to Combined Task Force 151’s intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) operations. Our MPRA force has developed its antisubmarine and ISR capabilities through training, exercises, and missions in operational conditions, alongside partner navies.

The JMSDF’s capacity for high-end warfighting is born of our traditional principles, which emphasize education, training, and exercises. Our warfighting capacity also can be attributed to our emphasis on learning from highly capable allied and partner navies. We believe our capability is in turn worthy for other navies to consider. The JMSDF promotes bilateral and multilateral training, exercises, and personnel exchanges to allow participating navies to incorporate new ideas and share lessons learned. Under Japan’s policy, the JMSDF will increasingly enhance cooperation and exchange opportunities such as training and exercises with partner navies. We expect to develop our capability and interoperability not unilaterally, but reciprocally.

In the Baltic Sea, the Lithuanian Navy provides significant MCM capability. Here the ships of the Lituanian MCM squadron, Jotvingus (N-42), Kursis (M-54), and Skalvis (M-53) train together at sea.

Lithuania

Captain Arunas Mockus,Commander of the Lithuanian Navy

Drastic changes in the global and regional security situation catalyzed the necessity to reinvigorate already existing naval cooperation, as well as to establish new formats of cooperation. The key challenges we are facing today in the Baltic Sea region are the significant military buildup of the Russian Federation Armed Forces and expansion of their antiaccess/area denial (A2/AD) capabilities which may pose significant threats to sea lines of communication in the event of crisis.

Consequently, maritime situation awareness is at the heart of the Lithuanian Navy’s ability to respond to rapidly changing situations at sea. The Lithuanian Navy actively participates in Sea Surveillance of the Baltic Sea project which is a cornerstone for sea surveillance information exchange and cooperation within the Baltic Sea area and its approaches. The aim of this cooperation is to enhance maritime situational awareness to benefit maritime safety, security, and environmental and law enforcement activities in the region by sharing relevant maritime data, information and knowledge between the participants. We also work closely with NATO’s Allied Maritime Command, exchanging maritime surveillance information with that command.

One of the long-standing regional cooperation projects is the Baltic Squadron—a standing mine countermeasures (MCM) unit consisting of assets and personnel from the Latvian and Lithuanian navies. This squadron provides both navies with a valuable opportunity to enhance interoperability and counter the threat posed by ordnance left from the two World Wars. It also serves as a training tool to prepare MCM units for deployments with Standing NATO Mine Countermeasures Group One.

The Baltic Navies Commanders Conference is a good example of a new regional cooperation initiative launched by the German Navy in 2015. Member navies participate in the activities of several working groups covering various spheres of cooperation, such as training and exercises, sea safety and information sharing, and doctrine development. One of the successful examples of cooperation between the German and Lithuanian navies developed in the framework of this initiative is the 2017 deployment of a Lithuanian Navy boarding team to the German Navy ship Rhein for Operation Sophia, the EU naval operation disrupting migrant smugglers and human traffickers in the Southern Central Mediterranean. The deployment resulted in the seizure of a large cache of smuggled weapons and the rescue of migrants.

Since 2016, the Lithuanian Navy has contributed vessel protection detachments to Operation Atalanta, protecting Somalia-bound vessels supporting the World Food Program.

While the Lithuanian Navy has a regional focus on the Baltic, it is striving to support cooperation initiatives beyond the Baltic, actively contributing to solving problems affecting the global maritime domain.

New Zealand

Rear Admiral John Martin

Chief of the Royal New Zealand Navy

At the heart of New Zealand’s national approach to economic and societal progress is our ability to trade on the world stage. Access to the global maritime commons is therefore essential to the health and viability of the country. New Zealand always has been a key proponent of the principles of the law of the sea, freedom of the seas, and access to the global maritime commons and trading routes.

The Royal New Zealand Navy (RNZN) has fostered strong partnerships that are based on the principles of interoperability, cooperation, joint and combined action, and strong inter-government relationships. We operate in some of the most challenging regions on the planet and deliver to a large mandate with a modest-sized navy.

The foundation of the RNZN’s approach to relationships is trust. You cannot surge trust: you have to build and nurture it. Given our geographic isolation and multiple tasks, our opportunity to influence partners through direct naval operations is limited. We must build and maintain trust so that our people and ships are accepted readily worldwide, and the value of our contribution is maximized.

New Zealand and the RNZN are trustworthy partners. Recently New Zealand ranked tied for first on the Corruption Perceptions Index of 2016, alongside Denmark. We also came first on the Government Defense Anti-Corruption Index. As a military organization we demonstrate our integrity on the global stage. Developing trust starts with personal integrity. We must be open, honest, and transparent to our partners. All in our Navy live our core values: courage, commitment, and comradeship.

We maintain security in our region as a trusted partner, working with our neighbors, protecting the global maritime commons, and recognising that security is a collective effort. By preventing corruption and upholding the network of laws and relationships known as international security, we protect the freedom of the seas, our nation, and yours.

Nigeria

Vice Admiral I.E. Ibas,

Chief of Naval Staff

The safe passage of ships and goods is among Nigeria’s vital maritime interests. Unfortunately, Nigeria’s maritime environment is bedeviled by multifaceted maritime security threats, including piracy, sea robbery, maritime terrorism, illicit trafficking in humans, small arms and narcotics, illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing, and crude oil theft and illegal bunkering.

The Nigerian Navy has the constitutional mandate to protect the nation’s maritime domain from these threats. Among the measures taken to address insecurity in the nation’s waters are the mounting of a dedicated antipiracy operation called Operation Tsare Teku and the introduction of a choke-point control regime to breach the communication of maritime resource thieves and other miscreants within the network of small rivers in the Niger Delta. Both of these operations have been highly successful.

Our Navy’s ships—as platforms that project naval power—are being recapitalized through local sourcing. At the same time, we are expanding training and quality of life for our naval personnel to strengthen our human capital.

To lessen the required operational logistics burden for deploying platforms and to make patrol efforts more mission focused, the Nigerian Navy has incorporated maritime domain awareness (MDA) facilities into its structure. We have acquired a national MDA network comprising the U.S. government-assisted regional maritime awareness facility, using the Falcon Eye system, to interdict criminal acts at sea.

In February 2016, our MDA network helped the Nigerian Navy rescue an oil tanker, the MT Maximus, with its crew of 18 and more than 4,000 metric tons of oil, three days after its hijack by pirates in Cote D’ lvoire waters. The criminal convoy was trailed and eventually intercepted at the fringes of Sao Tome and Principe waters with six pirates arrested and one killed in action. A major lesson from the operation is the increasing need for information sharing, security awareness, and international coordination.

Our Navy also has worked to improve interagency cooperation through overarching harmonized standard operating procedures (HSOP) to regulate all agencies concerned with the provision of maritime governance. These efforts brought Nigeria into immediate compliance with African continental and regional agreements encouraging member states to harmonize maritime law enforcement activities in an efficient manner through interagency synergy and cross-sector forums. Nigerian government operations under the HSOP are expected to deter criminals and strengthen the chances of securing justice against maritime offenders.

Collective maritime security also is being consolidated at the continental level across Africa. The realization of such initiatives as Africa’s Integrated Maritime Strategy (AIMS) 2050 and the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) Integrated Maritime Strategy (EIMS) has been a massive boost. These frameworks have guided the creation of cooperative capacity building. The zonal mechanism for maritime security operations among Gulf of Guinea states is a good example.

The Nigerian Navy played a key role in the development of both the AIMS and EIMS and was fully involved in the activation of the ECOWAS Pilot Zone for maritime security operations along with Benin, Togo, and Niger. The Nigerian Navy has also since 2011 sustained its participation in the annual Exercise Obangame Express, which brings together a number of the sub-region’s navies. Furthermore, it is a regular participant in international maritime discourse, which has seen it in many fora, concluding various bilateral agreements for improved maritime security.

Summing up, the best practice of the Nigerian Navy is its sustained advocacy for, and participation in, regional and international maritime security efforts through cooperative capacity building and collaborative efforts. Most nations have an increasing awareness that the combination of asset inadequacy, maintenance costs, and persistent maritime threats leaves most states and their navies with no other viable option than prudent capacity-building efforts in a collaborative model.

Pakistan

Admiral Zafar Mahmood Abbasi,

Chief of Naval Staff

Pakistan occupies an important geostrategic location proximate to the world’s energy highway. Being mainly dependent on sea trade, ensuring safety of sea lines of communication and a secure maritime environment in the Arabian Sea remains a core task of the Pakistan Navy (PN). Pakistan thus supports freedom of navigation on the high seas and considers maritime security a key enabler of global economic prosperity.

Nuclearization of the region, hegemonic designs of a regional country, and maritime terrorism stemming from instability in some of the littoral countries are destabilizing factors in the Indian Ocean region. Incidents of piracy—though reduced significantly in the Gulf of Aden—may reemerge unless instability and socio-economic deprivation are addressed in Somalia. We believe that no nation single-handedly can provide security in the maritime domain.

To contribute to regional maritime security, the PN joined Combined Maritime Forces (CMF) in 2004. In 2009, PN also joined Combined Task Force 151 (CTF-151) and became part of the counter piracy efforts in the region. PN officers have commanded CTF-150 and CTF-151 several times. As a singular contribution, PN has encouraged regional participation through its traditional and historical ties with Middle Eastern navies. It also has leveraged its local knowledge and influence through consistent and constructive engagement with these navies spanning over many decades.

Navies joining together improves interoperability and cooperation and leads to maritime security. To this end, PN has been organising the Aman series of multinational exercises biennially since 2007. The fifth exercise of this series was held in February 2017 with 35 countries participatint. The Aman exercise is a manifestation of Pakistan’s commitment towards peace and stability by bringing the navies of the East and West together under a common platform, embodying its spirit in the motto “Together for Peace.” In addition, PN is a regular participant in major multinational exercises and conferences held in the region and beyond.

We believe that oceans are the common heritage of mankind, and navies around the world have a shared responsibility of contributing towards collaborative maritime security. PN has made significant strides in advancing maritime security through cooperative engagements, commanding multinational task forces, organizing multilateral exercises, and promoting inter- and intra-regional partnerships. This is a unique and distinct strength of the Pakistan Navy and our best practice in promoting regional peace and maritime order.

In addition to maritime defense, the Peruvian Navy plays an important role in humanitarian assistance and disaster relief. Heavy rains and mudslides produced by the El Nino prompted such efforts in the mountains in early 2017.

Peru

Admiral Gonzalo Rios Polastri,

General Commander of the Navy

The Peruvian Navy, now 197 years old, has been known to reinvent itself throughout its history to adapt to technological developments, improving into a modern force capable of monitoring and protecting the nation’s maritime interests of enhanced maritime security at sea and on our many lakes. The long, thin geographic conformation of the Peruvian territory demands adaptable and flexible naval forces to project defense, provide internal security, and promote development in the seas, rivers, and lakes of the country. Peru’s geography includes a maritime area of ??more than 350,000 square miles, including 70 offshore islands and a 1,900-mile-long coastline. More than half of Peru’s population is concentrated in just over 10 percent of our land area along the coast. We also have a lake area of ??close to 2,000 square miles, and almost 9,000 miles of navigable rivers located in the Amazon region. The Amazon region comprises nearly 60 percent of Peru’s territory but contains only 12 percent of the population. Additional geographic challenges come from being an Antarctic nation, which the Peruvian Navy has embraced by recently adding our new polar oceanographic research vessel Carrasco.

The Peruvian Navy supports national foreign policy through the demonstration of naval power. We provide territorial self-protection while contributing to international security through participation in international peace operations (such as the United Nations missions in Darfur and South Sudan) and multinational naval exercises (such as UNITAS) and by strengthening interoperability and training and promoting synergies of cooperation and international relations.

Peru, as a member of the international community, promotes cooperation through active bilateral and multilateral agendas with regional emphasis. In many arenas, developing and sharing information are important parts of this cooperation. In November 2017, the Peruvian Navy presented a proposal to the Operational Network of Regional Cooperation of Maritime Authorities of the Americas to develop a maritime information fusion center for the Latin America region based in Callao, Peru. This center would allow the exchange of maritime domain awareness information with other nations’ information centers to help combat illicit trafficking, facilitate search-and-rescue operations, control pollution, and respond to maritime incidents and natural disasters.

The Peruvian Navy plays a significant role in humanitarian assistance and disaster response operations, both domestically and internationally. The most recent operation was carried out during the first months of 2017, as a consequence of the floods and mudslides produced by the El Niño phenomenon. The northern mountainous regions of Peru were affected and required naval and air forces to respond. The Navy provided logistical transport and established maritime and air bridges to reach victims in a timely manner. Six naval units, seven naval aircraft, and several rapid intervention companies for natural disasters participated.

The Peruvian Navy faces a diversity of tasks and challenges in different environments and scenarios. These challenges have required us to generate core competences that give us versatility and adaptability to change. We share these competencies with our regional and international partners.

Portugal

Admiral Antonio Silva Ribeiro,

Commander of the Portuguese Navy

Oceans are affected by a complex variety of risks and threats that need to be addressed as a baseline condition for responsible and sustainable use of the sea. To this end, the Portuguese Navy has a permanent focus on four fundamental maritime security pillars: maritime situational knowledge; interagency cooperation and coordination; multilateral cooperative security; and maritime security capacity building.

Maritime situational knowledge is essential to support decisionmaking by anticipating threats and risks, thus maximizing efficiency and effectiveness of our action at sea. In this field, the Portuguese Navy has developed, in partnership with a national information technology company, an innovative system called “Oversee,” which allows us to integrate and evaluate information from various military and nonmilitary sources to provide maritime domain awareness.

Interagency cooperation and coordination is increasing in importance because maritime security is not the responsibility of just one agency or just one country. In Portugal alone, there are more than ten organizations responsible for maritime security functions; in Europe, more than 300. Therefore, the Portuguese Navy partners with several national and international entities, particularly in the fields of fisheries control, counterdrug operations, and border and irregular migration control, particularly in the Mediterranean.

The Portuguese Navy is committed to multilateral cooperative security, as no nation, by its own, can ensure security in the vast maritime domain. In 2017, Portuguese warships, marines, and combat divers participated in several missions around the world, under NATO, EU, UN, and other multilateral partnerships. This included Portuguese frigates and submarines operating as part of the Standing NATO Maritime Group 1 and Operations Sea Guardian and Sophia, as well as command of the European Maritime Force and deployments in the Gulf of Guinea.

Finally, the Portuguese Navy has been involved in maritime security capacity building for more than 30 years, mainly with nations of the Community of Portuguese Speaking Countries, as we believe the most effective way to restore stability in maritime areas of strategic interest is by helping affected coastal states ensure their own maritime security. In January 2018, a new maritime operational capacity-building mission has been launched in São Tomé and Príncipe, involving the deployment of a Portuguese Navy patrol boat for one year.

As one of the oldest maritime nations in the world, Portugal depends on the sea for prosperity and the well-being of the Portuguese people, which explains why the Portuguese Navy is deeply committed to ensuring maritime security in the wide areas under Portuguese jurisdiction and sovereignty, as well as contributing to the security of the global maritime commons.

Spain

Admiral Teodoro Esteban López Calderón,

Chief of Naval Staff

No country or navy, no matter how powerful, can maintain freedom of the seas and ensure open access to the global maritime commons by itself. Naval partnerships and cooperation are necessary, both at the national and international levels. Adaptability of naval forces and interoperability among all players involved—civilian and military—are keys for success in maritime security.

During the past decade, as risks and threats in the maritime domain grew, the Spanish Navy increased its contribution to global maritime security, focusing not only on home waters but also in distant areas relevant to Spanish national maritime interests.

At the national level, the Navy reinforced interagency cooperation in the exchange of information and the conduct of operations. These efforts crystalized in 2015 with the publication of the Spanish National Maritime Security Strategy, which states the relevance of maritime security to Spain and places interagency cooperation at the highest level in the government structure.

In the international arena, the Spanish Navy deploys ships within multinational forces to fight piracy in the Indian Ocean and to counter human trafficking in the central Mediterranean Sea. Spanish Navy units also contribute to maritime capacity building in the Gulf of Guinea as part of the U.S.-led African Partnership Station or as national deployments. Our ships also take part on a permanent basis in the NATO Standing Maritime Groups, Operation Sea Guardian, and in regional ballistic missile defense.

Driven by these modern requirements, the core of the Spanish fleet is now made up of multipurpose ships: frigates (capable of acting in the whole spectrum of maritime tasks from counterpiracy to ballistic missile defense), maritime action ships (versatile, multipurpose offshore patrol vessels), and strategic projection ships (capable of deploying for a wide range of tasks, from disaster relief to amphibious operations). All these ships—conceived by the Spanish Navy, designed by Spanish shipyards (with some key U.S. technology partners), and built in Spain—provide flexibility and interoperability.

The high degree of cooperation and interoperability our Navy has achieved are not taken for granted. The Spanish Navy will continue to partner with allied and friendly navies and agencies to foster mutual understanding of maritime threats, strengthen bonds, share commitments, and integrate combined capabilities.

The Sri Lankan Navy used fast inshore patrol craft, such as these "Cedric" boats, to win a decades-long counterinsurgency against the Tamil Tigers.

Sri Lanka

Vice Admiral Sirimevan Ranasighe,

Commander of the Sri Lankan Navy

In the span of a few decades, the Asia-Pacific region has drawn world attention for many reasons, e.g., rising democracies, economic advances, nuclear proliferation, and growing military power. Simultaneously, the region was subjected to maritime security threats such as piracy, drug and human trafficking, illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing, and terrorism. These threats required regional alliances and cooperation.

An island nation surrounded by the warm waters of the Indian Ocean, Sri Lanka is not exempt to any of these maritime threats. For nearly three decades, the Sri Lankan Navy (SLN) pioneered modern-day asymmetric warfare against the ruthless Tamil Tigers (LTTE) terrorist organization, which was known to be the only terrorist organization with a naval capability. With limited assets but superior knowledge based on experience, the SLN was able to neutralize LTTE Sea Tiger attack craft, suicide squadrons, and a fleet of floating warehouses at sea. In these circumstances, naval cooperation, intelligence sharing, and sharing of a common maritime picture with other navies in the region were key factors that played a pivotal role in the last phases of the war against the LTTE. This experience is the foundation for our firm belief that, without cooperation and partnership among navies, maritime security is just a dream.

Against this backdrop, the Sri Lankan Navy hosted the international maritime security conference “Galle Dialogue 2017.” The theme of the conference was “Greater Maritime Visibility for Enhanced Maritime Security.” More than 40 countries participated and acknowledged the need for naval cooperation and partnerships for safer seas.

The SLN successfully protects our nation’s waters from exploitation by various illegal actors. The main reasons for our success are our naval platforms’ adaptability to multiple maritime tasks and their operational flexibility. Despite being a smaller navy, we put our heart and soul into naval partnerships, cooperation, and sharing our maritime picture with neighboring countries as well as global players in the maritime domain for safer seas in the Indian Ocean Region.

Members of the Swedish Amphibious Corps move ashore during the annual BaltOps Exercise in 2017.

Sweden

Rear Admiral Jens Nykvist,

Chief of the Swedish Royal Navy

Sweden is a nation with a coastline of nearly 1,700 miles, the longest of all Baltic Sea states, and with a history of developing and manufacturing everything (submarines, fighters, tanks, etc.) itself and with almost no international cooperation or participation in international exercises. This is not the case anymore. We still are building submarines and fighters (they are vital and considered as a national strategic interest from the political level) for example, but our international cooperation and participation has grown since the 1990s. At the end of the Cold War, we started to participate in small exercises. Today, we are participating in a whole spectrum of exercises providing stability and security in our region.

We have good cooperation with our neighbors, and in particular very close cooperation with Finland. This cooperation is growing every year, and in 2017 we declared initial operational capability (IOC) for the Swedish-Finnish Naval Task Group (SFNTG).

To use the Navy as a tool to build friendships, establish cooperation, and, most importantly, build trust among nations is perfect. Navies can start to meet in international waters executing small exercises and build from there. Use the Navy as a diplomatic tool by visiting neighbors in the region or far away building trust without a big footprint ashore. The freedom of the sea is unique and provides a wide range of opportunities to build trust.

All mentioned above is an example of how Sweden has developed its naval partnerships, cooperation, and interoperability. Today I consider that the Swedish Navy has come far in these matters. We participate in international operations together with partners and in exercises such as BaltOps, Northern Coasts, and Trident Juncture. NATO procedures are today standard and to cooperate with other nations is routine. Going from where we were to be a part of the Enhanced Opportunities Programme (EOP) is quite a step.

Cooperation is vital for Sweden. To build stability and security in our region we need to cooperate. With small numbers of ships and one amphibious battalion, we need to use our capabilities in the best way, and this is by cooperation. As an example: in an environment with 2,500 ship movements every minute in the Baltic Sea and the use of hybrid warfare tactics by different nations, it is vital to be able to create the best recognized maritime picture (RMP) to be able to act if necessary, and this can only be done by presence and cooperation.

The Royal Thai Navy participates in counterpircy operations in the Gulf of Aden.

Thailand

Admiral Naris Pratoomsuwan,

Commander-in-Chief, Royal Thai Navy

Faced with the tasks of maintaining freedom of the seas and access to global maritime commons while confronting growing threats and unexpected incidents, navies around the world have come to realize the importance of maritime cooperation and interoperability. Counterpiracy in the Gulf of Aden and Malacca Straits Patrol are two of many successful tasks in which the Royal Thai Navy (RTN) has participated alongside our international colleagues in the past decade. RTN officers were appointed commander of Combined Task Forces 151 twice, in 2012 and 2014. Forming successful partnerships and working alongside officers and vessels from other countries can be a daunting task to most of us mainly because of language and cultural differences.

The RTN believes one of the keys to our successful cooperation and interoperability with other navies around the world is the trust and understanding we have been building for many decades. Since 1922, RTN has sent our cadets and officers to attend naval academies and military institutes in various countries such as Britain, Germany, Spain, Japan, Sweden, France, the United States, Malaysia, Singapore, Philippines, Brunei, Australia, South Korea, and China. The language proficiency, insight, knowledge, and understanding that our cadets and officers gained from studying abroad have assisted RTN in communicating, planning, and working alongside our international counterparts in multilateral operations. During the past ten years, the RTN also has welcomed naval officers from ASEAN countries, Australia, and India for studies at our Naval Staff and Command College.

Seeing that building understanding and trust is an important key to successful cooperation, RTN proposed a high-level annual meeting where chiefs of ASEAN navies can get together to foster relationships and exchange their views on maritime security issues within the region. The first meeting was held in Bangkok in 2001 under the name ASEAN Navy Interaction and later changed to ASEAN Navy Chiefs’ Meeting (ANCM). Recently, the 11th ANCM was successfully held in Pattaya, Thailand, in November 2017. During this meeting, issues such as protection and preservation of the marine environment, and anti-sea robbery cooperation (ASRC) were discussed and agreed on.

Modern equipment and common procedures and regulations will provide easier working environments, but understanding and trust are critical success factors for future cooperation and interoperability. The RTN will continue to build trust and understanding with our colleagues through education programs, training, exercises, and operations to make sure we are ready to be part of the global naval forces in maintaining freedom of the seas and access to global maritime commons.

United Kingdom

Admiral Sir Philip Jones,

First Sea Lord and Chief of Naval Staff

We live in an age in which warfare and the maritime environment are increasingly characterized by automation, robotic systems, and artificial intelligence; an age in which information and computing power seem to dominate. But despite this, our people remain our greatest asset and the source of our combat power. The sailors of today’s Royal Navy share a culture and enduring traits their forebears would recognize. Quick to meet challenges with resourcefulness, and good humor, they are resilient, robust, and take strength from a distinguished past; the fate of our nation has rested on their shoulders countless times for more than 450 years.

We also should remember that our sailors’ resilience and commitment, and consequently their combat effectiveness, are underpinned by the professional and personal care that is provided to them and their families. This is no accident; we should reflect that the care delivered through the divisional system is a deliberate choice that we must prioritize and is without doubt one of the Royal Navy’s best practices. Borne of a need for more humane treatment, health care, and discipline in the middle of the 18th century, it is as relevant today as it was then.

Our people possess an incredibly varied range and depth of skills; the Royal Navy is not alone in this and, like many of our partner navies, we are adapting individual training now to meet tomorrow’s threats. But, of course, if we wish to be ready to fight and win alongside partners and allies, we must train our teams together to meet shared and exacting standards. The world-class training delivered by the Flag Officer Sea Training (FOST) does just that, and those who have experienced it will recognize the advantage this brings.

So, in a future rightly dominated by automation and artificial intelligence, we must continue to emphasize the primacy of people in this enterprise, whether reserve, regular, or civilian. We must continue to put the care of our sailors at the heart of our endeavor and tailor their training to provide them with the skills required in a rapidly changing world. We need to carefully consider the benefits and limitations of unmanned capabilities and put our people where their unique attributes deliver complementary battle-winning edge. And if we are to operate routinely in partnership, as we do today—interoperable and integrated—we will need to undertake this journey together, as partners and allies.