In 1970 in the Mediterranean, the USS Independence (CVA-62) and the Soviet destroyer shadowing her activated their fire-control radars and locked onto each other. The author, a young ensign at the time, recalls his disappointment when the tensions came to naught but concludes the strength of Sixth Fleet kept the Soviets from pushing too far.

The sea was an ebony carpet with only the faintest indication of a horizon separating the overcast sky from the waters below. Yet, through my binoculars, I could make out the silhouette of a Soviet destroyer off our starboard quarter, gliding silently, with a slight left-bearing drift. “Ivan”—as we had nicknamed him—had been shadowing us for several days and was less of a novelty than he had been when first arriving to take the place of the smaller, less lethal intelligence collector (AGI) that had been our companion since the crisis began.

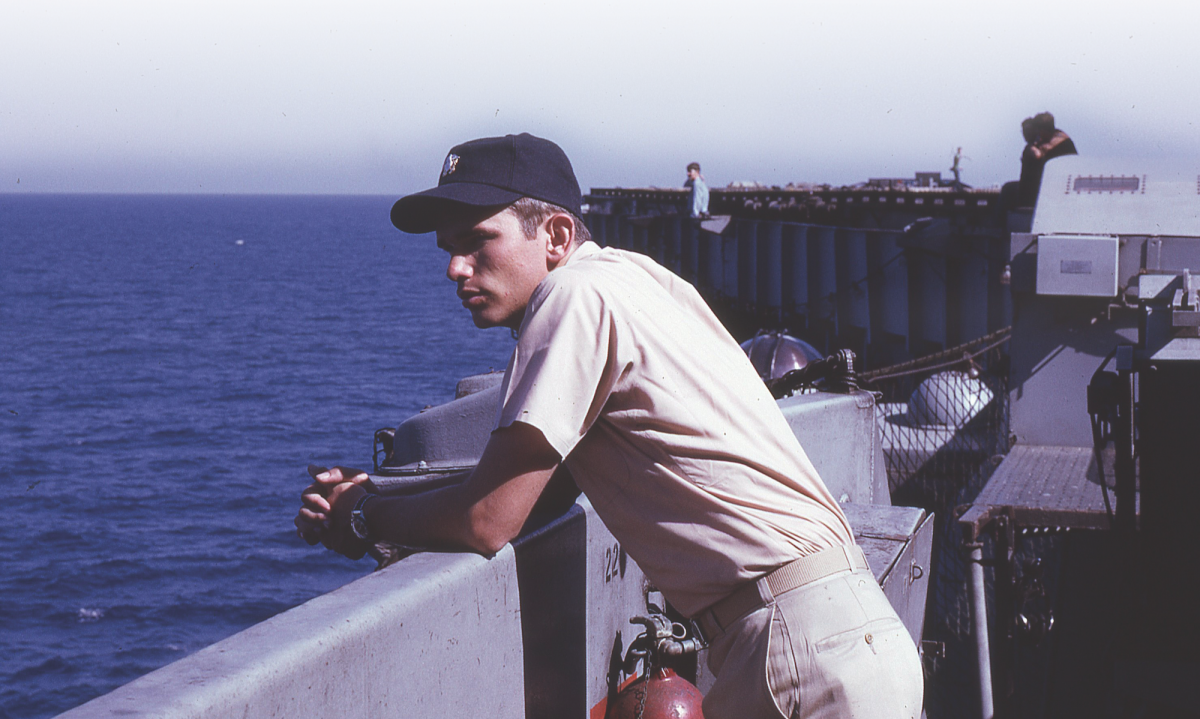

As junior officer of the deck and conning officer of the aircraft carrier USS Independence (CVA-62, “Indy” to those of us privileged to serve as part of her 5,000-man airwing and crew), my primary concern on this midwatch was navigational, including being ready in case Ivan made any sudden moves—as he had done several days before—that might risk a collision. On that earlier occasion, we had been recovering aircraft, and his sudden turn seemed deliberately designed to disrupt our flight operations.

Such interactions between adversaries in the Cold War were not unusual, but at times like this, when there was a crisis in progress among the client states of the two great contenders, the level of danger was markedly increased.

As an ensign, I was not privy to much detail and consequently had little understanding of what was going on. All I knew for certain was that something was happening in Jordan; that upon departing Athens after a scheduled visit, we had been ordered by flash message to “point three-three north, three-three east” (just more than a hundred miles from the coast of Israel); that another carrier was on her way to join us; and that the aviation ordnancemen in my division had just completed a major load of antitank weapons onto many of our A-4 and A-6 attack aircraft.

It seemed something major was afoot and that we might actually be involved in combat operations. But it did not take a strategic genius to know that as long as the Soviets were involved, there likely would be great restraint—hopefully on both sides—because the specter of nuclear war loomed ever-present, unimaginable yet unquestionably real. Still, as a young and naive sailor, who had not yet experienced combat but had read a great deal of history, I could not help but feel excitement at the prospect of getting to do what we had trained for, to follow in the wake of John Paul Jones and go “in harm’s way,” to strike a blow against the Red enemy I had learned to abhor.

I recently had volunteered for duty in Vietnam, and in a few months I would go there and have some of that naivety scrubbed away—though I still would abhor Communists, albeit with a newfound and grudging respect. But in September 1970, my task was to drive an aircraft carrier through the dark waters of the Mediterranean Sea, to watch a potential enemy brazenly shadow us, and to wonder what the coming hours might bring.

I was nearing the end of my watch when a voice on the 21MC startled me from my musings: “Bridge, Combat; Ivan is lighting us up.”

Realizing this meant the Soviet destroyer had activated its fire-control radar and was targeting us, I felt the hair stand up on the back of my neck. My excitement increased as the officer of the deck called the captain, and the latter emerged from his sea cabin, shuffling along in slippers and ordering our own fire-control radar to retaliate by locking onto the offending Soviet ship.

For the next half-hour, Ivan and the Indy remained locked on one another, poised like two fighters squared off in the ring, but neither throwing a punch. At first, I wondered if this was “it,” the moment when the proverbial balloon would go up, and I would see a flash erupt from our Russian “escort.” But as both ships continued to steam along as before, neither changing course nor altering speed, and the captain did not order us to general quarters, I realized this was merely harassment without true hostile intent.

My excitement was replaced by an unreasoned but very real feeling of disappointment. I had joined the Navy for many reasons (not least was my belief that women could not resist a man in uniform), but one of my motivations was to be a warrior. I had grown up in the streets of Baltimore, where the most noble form of fighting was self-defense, all others for stupid reasons. My reading had revealed to me that fighting could be for truly altruistic reasons, that worthwhile endeavors—like freedom and justice—could not survive without those who were willing to fight and even die to protect them. I wanted very much to be one of those noble warriors.

That honorable motivation, coupled with a young man’s foolish desire to “prove himself” by achieving some form of heroism (that also would impress the fairer sex), caused me to feel a level of disappointment that even my young self knew was misguided but was intense nonetheless.

As the adrenaline ebbed, I stared out at our Russian adversary, seeing only his running lights contrasting sharply with the Stygian darkness, their brightness another sign that there would be no combat on this midwatch. Masked by the low hum of electronics and the ever-present static from the high-frequency radio speaker, I could hear the muffled voices of the helm and lee-helm watchstanders as they spoke, most likely about their adventures in the last liberty port. It was clear the tension we all had felt was subsiding. With a heavy sigh I turned away and prepared for the changing of the watch.

But this essay is not really about me. It is about two powerful fleets that represented their respective superpower nations in those dark days of the Cold War, when the world held its collective breath knowing that a miscalculation by either side could result in a nuclear holocaust. It is about the motivations that brought these armadas into frequent contact, the varying roles they played—sometimes threatening, sometimes yielding—and the decisions that brought them—more than once—into confrontations that were heralded by the thundering hoofbeats of the Four Horsemen as Apocalypse loomed just over the horizon.

It was in the midst of one of those ominous confrontations (the Jordanian Crisis of 1970) that I experienced those contradictory feelings described above. By the time I found myself in the midst of another such confrontation (the even more ominous 1973 Arab-Israeli War), I had been to Vietnam, added a wife and children to my seabag, and gained a more realistic appreciation of the spectrum of warfare and its consequences.

In that second confrontation, I had a better understanding of what was happening and, more important, what was at stake. Although I remained prepared for a hostile exchange with our Soviet adversaries and was willing to accept the personal consequences, I no longer felt the same level of disappointment when tense moments subsided without overt action. In the years between those major confrontations, when the U.S. Sixth Fleet stood toe-to-toe with the Soviet Fifth Eskadra, I had learned to include bloodshed in my calculus of consequences, and I now appreciated that the loss of restraint I once had resented now threatened my loved ones at home as well as me, the “noble warrior.”

So it was that the lieutenant’s view of Sixth Fleet operations was more advanced than that of the ensign, certainly more mature and better informed. Even so, I still did not fully appreciate what I (the Sixth Fleet) was doing during my multiple deployments. I often selfishly wondered why we needed two task groups in the Mediterranean when one would allow me more time at home with my family. I frequently dismissed fleet exercises as just another way of making sure morale did not get too high. I saw port visits as little more than a great way for the Navy to fulfill its recruiting promise to “see the world.”

It has been in later years, when I have long since traded my sword for a pen and reaped the benefits that the passage of time confers on those who have discovered the utility of history, that I have learned so much more about what we Sixth Fleet sailors were doing on those deployments to Homer’s “wine dark sea.” I now am able to see some of what the admirals saw, to know why we were asked to make the sacrifices and take the risks that we did. I now can visit flag bridges, read documents once beyond my clearance and “need to know,” and listen in on conversations within the walls of the White House and the Kremlin.

Out of all that, I learned the value of those many hours participating in exercises that seemed trivial at the deckplate level, I grew to appreciate the importance of “carving holes in the ocean” (as we inelegantly described maintaining a station in some corner of the Mediterranean), and I came to know how very close we came to Armageddon, sometimes without being fully aware.

Some of the conclusions I drew as a result of this quest resonate today, for despite tectonic shifts in geopolitics—not least of which was the demise of the Soviet Union—the Mediterranean remains a vital sea of great strategic significance, the Middle East and North Africa continue to demand the attention of both the United States and Russia, and maritime strategy is every bit as important as it was in those days when the Sixth Fleet and Fifth Eskadra pointed their weapons at one another.

The story of confrontations between the U.S. and USSR fleets is one fraught with peril, one that might well have ended badly. We several times came frighteningly close to Armageddon, where a moment of panic or a slight miscalculation, or the presence of a madman at the wrong place at the wrong time, could have upset the delicate balance that kept both sides from going beyond “the brink.” But in the final analysis, it was the strength of the Sixth Fleet—real and perceived—that on each occasion prevented the Soviet Union from pushing too far and prevented crises from becoming catastrophes.

The experiences of the Sixth Fleet are a classic study in those vital missions that make a strong Navy worth its cost—primarily forward presence and deterrence. What the layman (and a young ensign) usually fails to comprehend is that navies succeed when they prevent war; that the ability to go to war—and to win—is essential, but it also represents a partial failure in the navy’s primary purpose of defending the nation, a choice (or necessity) of last resort.

The victory at sea during World War II is a source of great pride to those Americans who know their history. We understandably—and in one sense rightly—often focus on the courage and sacrifices that allowed our sailors to win the greatest sea war in history. Yet such focus masks the fact that it also is a story of failed strategy, because the nation’s weakness opened the door to that horrific conflict by allowing our enemies to believe they could prevail, to challenge us in the North Atlantic and to attack us at Pearl Harbor.

In the postwar years, by its constant presence and its strength, the Sixth Fleet succeeded in preserving vital national aims while preventing another holocaust, one that likely would have had even greater consequence and would not have ended in clear victory for either side. The lesson here is obvious and old—peace is best achieved through deterrent strength.

These musings are relevant because grave dangers continue to haunt us in an era when many of the methods—and indeed the rules—of war are changing. Those dangers we faced during the Cold War may have changed their appearance and may be affected by different variables, but they are no less dangerous and still require vigilance, valor, and preparedness to keep them in check. The fact remains that the most effective way to deter war is through strength—and, somewhat contradictorily, a willingness to use it.

The surest way to disaster is to permit potential enemies to believe they can prevail. Among the very first lines of defense is our Navy—able to deter through mobile presence, to preserve those sea lines of communication that bind the world together in trade, and to project formidable power when all else fails. Yet these seemingly self-evident truths are little understood by the public at large and by too few of the legislators who represent them.

The lessons subsequently learned by this sailor—who once stood watches in company with a dangerous enemy, who only partially appreciated the importance of what he and his fleet were doing—are lessons that must be more efficiently learned by those who hold the keys to the Navy’s future. My naivety as an ensign was curable over time and was of no real consequence as long as I was willing to follow orders, but as a nation we cannot afford such a slow edification process. We do not have the luxury of waiting for decision makers to learn how to make the right choices—budgetary and strategic—while we grow weaker and our enemies grow stronger.

Imagine a world where China controls the South China Sea, Russia dominates the Mediterranean, and Iran decides who may or may not access the Persian Gulf. These are not overnight occurrences, but a strong navy cannot be maintained without the proper long-term investments in shipbuilding infrastructure, cutting-edge technology, first-rate personnel management, and sustainable maintenance programs. And these investments are not likely to be made by individuals who think like Ensign Cutler and who do not understand the imperative of a strong navy to a maritime superpower such as ours.

Among the Navy’s highest priorities should be an effective information campaign that warns without hysteria yet clarifies the perils that lie ahead if we allow our fleet to atrophy through ignorance. Americans must realize that this is about more than national defense—it is about free trade and the maintenance of mechanisms that preserve the standard of living we take for granted.

The power of social media and other forms of communication must be exploited to deliver this vital message. Peace through strength must be more than a bumper sticker; it must be a commandment of national survival and well-being. If this nation is to safely navigate the shoal waters that loom ahead, it must strive to edify and inspire those outside the choir, to illuminate for others what too few citizens understand, to recast strategic thinking as common sense.

To do otherwise is to invite empty shelves at Walmart . . . or worse.

Lieutenant Commander Cutler enlisted in the Navy in 1965 and was commissioned as an ensign in 1969, retiring in 1990. He is the author of several Naval Institute Press books, including A Sailor’s History of the U.S. Navy and The Battle of Leyte Gulf, and is the U.S. Naval Institute Gordon England Chair of Professional Naval Literature.