Long the centerpiece of the U.S. Navy, the aircraft carrier will become a more focused player.

Since the end of the Cold War, the U.S. Navy has enjoyed more than two decades of unchallenged supremacy on the world’s oceans. With its global reach, it has become accustomed to deploying warships in support of its national interests wherever needed with virtual impunity. The activities of would-be competitors and recent developments in naval warfare, however, suggest its “Long, Calm Lee of Trafalgar” is about to run out.1

The centerpiece of U.S. power projection has been the nuclear-powered aircraft carrier, a hugely expensive but immensely flexible asset that can conduct almost every naval role imaginable. Today, the carrier does have some growing limitations when facing first-rate opposition. Operationally, the problem has two parts. First, the radius of action of the offensive piece of the carrier’s arsenal, the air wing, has been allowed to decline with successive generations of tactical aircraft. The commonly quoted figure of around 500 nautical miles is about half that of an equivalent air wing in the 1960s. Second, new developments in precision antiship weaponry, most notably the Chinese DF-21D “carrier-killing” ballistic missile, promise effective ranges of roughly double this figure, thereby exposing the ship to significant risk. In addition, wildly escalating costs, both in procurement and operation, and the proliferation of less expensive delivery systems for precision ordnance have combined to make the naval aviation option less attractive in the longer term. In the words of one author, “If the fleet were designed today, with the technologies now available and the threats now emerging, it would likely look very different from the way it actually looks now.”2

While legacy platforms serving out their time are an unavoidable fact of life, the institutional bias that navies can have toward them and their accompanying doctrine bear investigation. If it can be illustrated that the carrier is being kept in an artificial position of prominence within the fleet, for institutional reasons, then the U.S. Navy has a problem. Obviously, force planning has to be fluid, with national needs constantly evolving to suit the developing situation. Theoretically, many of the carrier’s shortcomings still could be fixed with a focused infusion of monies and research, but some missions might work out as more expensive alternatives to similar outcomes promised by emerging technologies. In effect, the viability of the carrier in strike missions is eroding, and as a result the carrier’s position vis-à-vis the rest of the fleet is changing. Instead of being the centerpiece, it likely will become an important but more narrowly focused role player.3 The question is not so much whether the carrier can be updated, but whether the Navy is willing to accept this change to its position within the fleet.

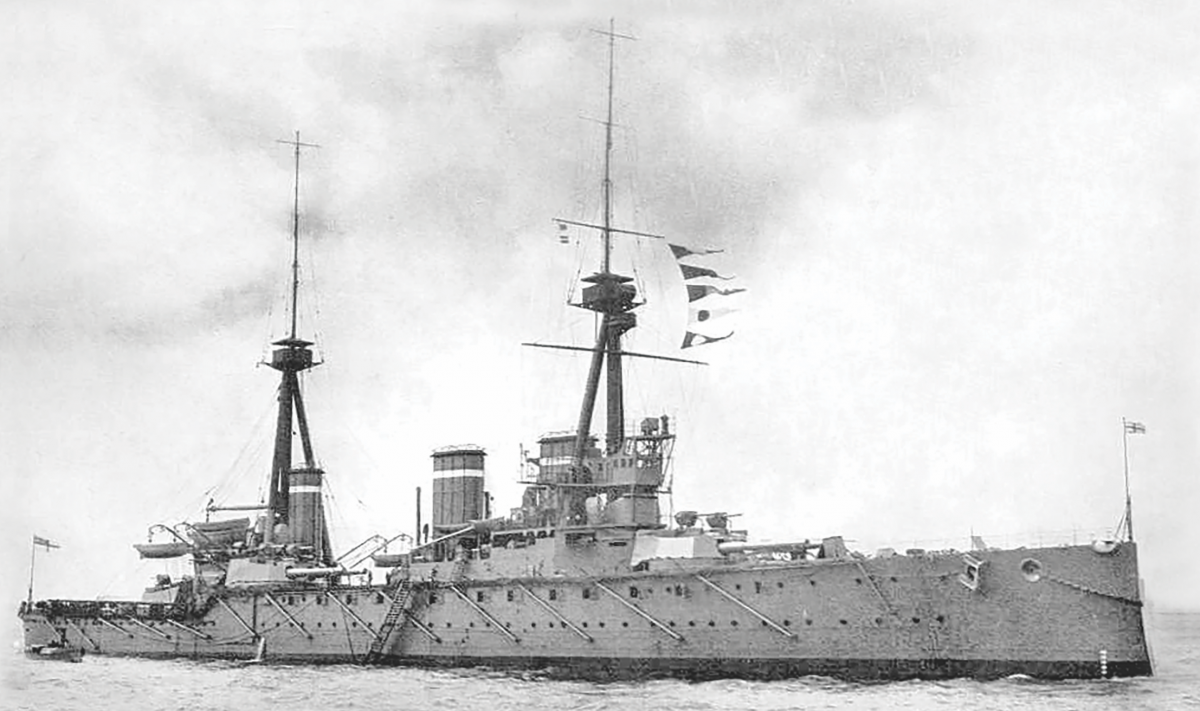

HMS Invincible (1907), the first of her class of “super cruisers,” resulted from Admiral Fisher’s radically different vision of naval warfare and his determination to maximize advances in technology.

The Royal Navy Has Been There

It is instructive to consider how others have dealt with change. The aim should be to look for parallels without being prescriptive, because each period has its own unique set of personalities, politics, and geostrategic circumstances. Without doubt, Great Britain in 1900 was a naval power that had long enjoyed a position of peacetime maritime primacy. Yet, with the conflicting prospects of a slowing economy and a burgeoning imperial defense budget, the Royal Navy was facing the need to make real economies at precisely the time it was facing new challenges from rivals in Europe.4 The parallels with the U.S. Navy today are remarkable.

In 1900, the established “measure” of sea power was the battleship, which was becoming similarly costly to develop and maintain as today’s aircraft carriers. In the 20 years immediately preceding, there had been an exponential rise in the size and complexity of successive generations of these combatants. The recent development of torpedoes and mines, however, also had made them vulnerable, particularly in coastal waters, and not just to their own kind. Because any smaller navy theoretically could develop torpedo craft, questions arose as to the utility of the line of battle. In the words of Admiral Sir John “Jackie” Fisher:

The Battleship of olden days was necessary because it was the one and only vessel that nothing could sink except another battleship. Now every battleship is open to attack by fast torpedo craft and submarines. Formerly, transports or military operations could be covered by a fleet of battleships with the certainty that nothing could attack them without first being crushed by the covering fleet. Now all this has been absolutely altered! Hence what is the use of battleships as we have hitherto known them? none! Their one and only function—that of ultimate security in defense is gone—lost!5

Finally, but no less influential, the prevailing “Mahanian” doctrine of the day held that these battleships should be kept together as a concentrated fleet. This was because it was the combined power of the whole fleet that maximized the probability of success in battle and therefore held the deterrent value so prized by statesmen. This had led to a reluctance by most powers to either split their fleets or to allow them to stray too far from the potential field of battle. At the same time, the emerging mercantile nature of the Industrial Age and its associated “scramble” for resources overseas had created a seemingly insatiable demand for imperial policing and diplomacy duties abroad.

This dichotomy did not sit well with the idea of concentrated battleship fleets, forcing navies to consider an additional need for whole classes of “cruising ironclads,” or “cruisers.” Even though they were considerably cheaper at the outset than the battleships, they were destined to grow in both complexity and size. Of course, expenditure on these classes was “over and above” the continuing need to provide for a battlefleet, a factor that made the fiscal situation even more precarious.6

In an attempt to limit these expenses, navies tended to use older ships on the imperial beat as “station” cruisers. This followed the rationale that a cruiser, obsolescent for a scouting commission in Europe, still could serve with credit abroad, where the likelihood of it encountering sophisticated opponents was slim. For a while this policy worked well, but with the advent of faster, long-range, armored cruisers developed specifically for distant water operations by France in the 1890s, the days of a ship living out her twilight years abroad looked to be numbered. Unfortunately too for the British, the massive growth in imperial responsibilities had led to huge increases in the numbers of vessels overseas, and the prospect of replacing them all with first-rate, armored cruisers was daunting.

Fisher’s Mandate: Reform the Navy

Luckily, Fisher, the mercurial, chief instigator of the Royal Navy’s reforming movement, was about to arrive at the pinnacle of the uniformed navy with specific tasking from his First Lord to address this need for savings.7 To Fisher, all these “legacy” constraints were frustrating. If maritime primacy were to be preserved, then surely the only responsible way forward was to accommodate these savings by adopting a radically different vision of naval warfare that he believed advances in technology were on the verge of delivering. He was calling for a “capabilities-based” review of everything the Royal Navy was trying to do.

As Fisher explained, “In approaching . . . ship design, the first essential is to divest our minds totally of the idea that a single type of ship as now built is necessary, or even advisable.”8 Even more worrying than the vulnerabilities of battleships to torpedoes and cruisers to the newer, armored ships, however, was the manpower situation. Because of the growth in the number of cruisers scattered around the world, a large percentage of the navy’s available manpower was committed abroad on stations where it could learn little about the techniques and drills associated with modern warfare. To Fisher, this was an unforgivable waste in an era where naval warfare increasingly would be characterized by its suddenness.9 He believed the Royal Navy simply could not afford to keep such a high percentage of its human capital essentially “untrained.” In addition, he needed these men to man the revolutionary new fleet he was about to develop.

Fisher’s elegantly simple solution was to play to the strengths of the new technologies. If submarines and torpedoes were making the shallow seas unacceptably risky for the battlefleet, then move the heavy ships out of harm’s way and rely on those same systems in British waters to deter any potential invader. Fisher argued that Britain needed to develop “flying squadrons” of even more powerful “super-cruisers” that could respond quickly to events around the world, and it should do away with all the old ships permanently based overseas. In effect, submarines and these “super cruisers” would take the place of the battleships, the armored cruisers, and the station cruisers with the promise of the same degree of “naval influence” and considerable savings.

Innovate

Of course, these concepts required more capable submarines and faster, more powerful cruisers than existed in 1904, not to mention a reliable system of wireless telegraphy to provide the necessary intelligence and direction.10 In particular, though, if Fisher’s cruisers were to use their speed to advantage and still prevail in combat with raiders overseas, then they would have to be able to deliver a knock-out blow from long range, something that had been proving elusive. Again, Fisher believed technology would provide the answer. He concluded that the modern heavy gun and a true-course calculator being developed by Arthur Pollen were about to provide a revolutionary solution to the problem of long-range hitting. It is important to appreciate that the idea of a lightly protected ship being able to strike with impunity beyond the effective range of its opponents depended on this fire-control problem being solved in short order. In essence, there could be no effective “cruiser-killers” without first having an accurate, long-range gun. Thus Pollen’s invention was vital to Fisher’s plan.

Fisher’s drive notwithstanding, Great Britain did not radically alter its naval strategy, or at least not within a timescale that would have given some lasting value. Some battlecruisers were built and many obsolete ships were decommissioned, but somehow the clarity of purpose that had guided Fisher was lost on the broader institution. Instead, Britain plunged headlong into another round of battleship escalation, while attempting to maintain parity across the board in all classes of naval vessels. The results were predictable, and financial exhaustion was only averted by the onset of a European war and the consequent readjustment of national priorities. So what exactly went wrong and why?

This was not just another case of unfulfilled technological promises. After all, the British were innovating; they were producing revolutionary advances in gunnery, submarines, and propulsion, and all within a remarkably tight time frame. Similarly, British industries were doing a commendable job of developing these technologies into workable weapon systems, and they were doing so at a rate equivalent or superior to that of the competition.

See the harsh Realities

Some warn that it never pays to become too specialized in times of strategic uncertainty. There are hints of this with the Fisher plan, but with one very important caveat. The British policy of “wait and see,” when it came to innovation, did not serve the navy well, because only it was in a position to drive strategy.

Certainly, the strategic situation had changed. In the three decades before Fisher’s revolution, both the French and the Russians, who had been outclassed by the British battlefleet, made considerable efforts to challenge Britain with worldwide commerce raiding. By 1905, however, France was becoming increasingly aligned with the British through fear of a rising Germany, and Russia was temporarily out of the naval picture, having suffered devastating losses in the Far East. This left only Germany as a credible threat, and lacking the necessary global infrastructure, it was in no position to threaten commerce in the way that France and Russia once had, even if Germany unquestionably had the technology. Thus, in suggesting the switch, Fisher had taken a calculated risk that the future would continue to require an active, global role for the Royal Navy. Even at the time there were many who disagreed, recommending instead that Britain bide its time until the situation clarified.

Great Britain and its Royal Navy were, however, different. Like the United States and its Navy today, Great Britain held the premier maritime power of its day, and it took a wait-and-see approach instead of forcing the pace. This is not the best course for navies in such circumstances. The French attempted to compete from a position of inferiority, forced to respond in a predictable manner to whatever approach the more powerful navies took. The British, on the other hand, had no such encumbrance. Having the world’s premier navy, the British were uniquely free to make naval choices, secure in the knowledge that well-chosen steps were sure to cause competitors even greater headaches by driving them into areas that might be less advantageous to them.11

Today’s Premier Navy Must Learn

• Supreme military power provides a unique opportunity to make strategic choices. This is perhaps the most important lesson for the U.S. Navy.

• The second lesson concerns the inability of an institution to recognize when a fundamental change offers some alternatives that can generate disproportionate advantages. In the British case, the Admiralty, preoccupied with its enthusiasm for the minutiae of naval technology and the prospects of fighting a second “Trafalgar,” seemed slow to recognize that the Industrial Age had changed the very nature of naval warfare, particularly for the world’s largest navy with a global trade dependency. From this point, naval decisions were going to depend less on decisive engagements at sea and more on how naval activities might affect the broader business of safeguarding a nation’s economy and its crucial ability to generate combat power in its widest sense. In short, the business of exercising “sea control” had widened considerably.

• Although Fisher may have understood the need for change, he did not make it easy for the institution to move in that direction by shrouding his thoughts in secrecy. Whether this was motivated out of concerns for security or for personal gain, it is impossible to say. What is clear is that this approach generated resentment and suspicion, particularly from those with other ideas, a tension that ultimately impaired his ability to function as an effective leader.12 The lesson here perhaps is to be less polarizing. Never assume everyone will understand instinctively; be a patient advocate and a good listener all at the same time.

• Fourth, education and manpower systems must be geared to attract, identify, and develop the Fishers, Hyman G. Rickovers, and John R. Boyds of this world. A navy needs to nurture and develop a questioning professional service culture. The key to this is a widespread and thorough professional education so that a culture of risk taking and evaluation is encouraged at all levels. The British were halfway there, in that they were innovating, but their parochial officer corps was incapable of making the necessary leap in thought from the battle line to global power projection. War colleges today should focus more on encouraging original, creative thinking in whatever form it appears. Manpower specialists can assist by developing systems to identify specific talent within the service and by directing it along appropriate career paths.

This case serves as a salutary warning of the powerful and often unforeseen effects this combination of human elements, changing strategic imperatives, and technological risks can exert on even a well-structured and mature plan. Fisher was a gifted administrator, blessed with immense moral courage and an insatiable energy and drive. He also had an almost unfettered access to power. Still, even he was to be diverted from his vision by this insidious combination. For all these reasons it is important to analyze cases like this; otherwise mistakes are destined to be repeated. Preserving the carrier’s position may indeed be the answer in this case, but the fact is no one knows for sure at the moment.

1. Andrew Gordon, The Rules of the Game (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1996), 155.

2. Henry J. Hendrix, “At What Cost a Carrier,” CNAS Disruptive Defense Papers.

3. Robert Rubel, “The Future of Aircraft Carriers,” Naval War College Review 64, no.4 (autumn 2011): 24–25.

4. See Arthur Marder, From the Dreadnought to Scapa Flow: The Royal Navy in the Fisher Era, 1904–1919, 5 vols. (London & New York: Oxford University Press, 1961–70). Notable among more recent works is Jon Sumida, In Defense of Naval Supremacy (London: Unwin Hyman, 1989), challenging Marder’s geopolitical basis for the development of the Dreadnought and the battlecruiser. See also Nicholas Lambert, Sir John Fisher’s Naval Revolution (Columbia; University of South Carolina Press, 1999), which introduces the concept of “flotilla defense” and shows that Fisher’s faith in the submarine provided the home defense capability that would allow the capital ship to be a reactive defender.

5. See P. K. Kemp, ed., The Papers of Admiral Sir John Fisher, vol. 1 (London: Navy Records Society, 1960), 30–31.

6. Sumida estimates that this and the cost of the Boer War (1899–1902) caused the United Kingdom’s national debt to increase by a quarter. Sumida, In Defense of Naval Supremacy, 23.

7. William Waldegrave Palmer, 2nd Earl of Selborne, British politician and colonial administrator, was First Lord of the Admiralty (SecDef equivalent) in 1900–1905, and Fisher became First Sea Lord in October 1904. See Marder, ed., Fear God and Dread Nought: The Correspondence of Admiral of the Fleet Lord Fisher of Kilverstone, 3 vols. (London: Jonathan Cape, 1952–59), vol. 1, 278–332.

8. Kemp, ed., The Papers of Admiral Sir John Fisher, “General Outline of the Scheme,” 40.

9. For Fisher’s thoughts on the “suddenness” of modern naval warfare requiring “an instant readiness for war,” see Kemp, ed., The Papers of Admiral Sir John Fisher, vol. 1, 16–27; and a letter to Lord Selborne written in April 1904, Marder, ed., Fear God and Dread Nought, vol. 1, 310–11.

10. Nicholas Lambert, “Strategic Command and Control for Maneuver Warfare: Creation of the Royal Navy’s War Room System, 1905–1915,” Journal of Military History 69, no. 2 (April 2005): 361–410.

11. Sir Julian Corbett, “The Strategical Value of Speed in Battleships,” RUSI Journal 51, no. 2 (July–December 1907): 824–33.

12. See in particular an anonymous article written in Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine 177 (May 1905), 597–607, titled “A Retrograde Admiralty.” This was widely attributed to Rear Admiral Sir Reginald Custance, lately the DNI, who was extremely critical of Fisher’s methods. Custance criticizes Fisher for deliberately undermining the authority of the other Admiralty board members, and in particular the controller, thus effectively turning it into a dictatorship.

Commander Ross is a professor on the faculty at the U.S. Naval War College in Newport, Rhode Island. An antisubmarine warfare specialist, he served variously in Her Majesty’s ships around the world. He holds a master of arts degree in national security and strategic studies from the War College (1998) and a second master’s degree in European history from Providence College (2005).