It often is the case that significant decisions, made for good reason, have unintended consequences. Recent incidents in the surface force indicate it is time to revisit the executive officer (XO)/commanding officer (CO) fleet-up model. While there are other possible common threads and any number of variables in the Fitzgerald (DDG-62) and John S. McCain (DDG-56) collisions, and while it may be too soon to draw conclusions about root causes, it is not too soon to start the conversation.

Not Enough Jointness

In the early 2000s, the Navy had a problem. Its surface warfare officers (SWOs) were not competing well at the flag level for two main reasons: (1) late selection to captain because of the timing of commander command tours, and (2) not enough contenders for admiral completing a joint tour—a requirement under the Goldwater-Nichols Act. A waiver was established to reduce the 36-month joint tour requirement to 24 months for those officers selected for command at sea, but it eventually was eliminated. After 2010, it was challenging for the “due course” officer to pass through the wickets required to make flag: a master’s degree, a joint tour, and (preferably) a “blue” tour in the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations or somewhere in Washington.

Some mitigation could be found by reducing department head sea tours, including by instituting a weapons/combat systems officer fleet up for Aegis ships and making the second department head tour at a destroyer squadron or an amphibious squadron. XO tours could be shortened to support attendance at a war college, and operational detailing could be used to push a commanding officer through a deployment and then an early-promote fitness report, moving him or her on to the required shore-based wickets before moving to major command—the final tour necessary for flag eligibility. This patchwork of potential mitigations required a great deal of creativity, flexibility, and often multiple permanent change of station moves or geographic bachelor tours. Something had to give.

Joint Duty Sooner, Sea Duty Later

Thus was born the “fleet-up” plan, long used with great success by the naval aviation community. Like any major change, it had detractors and proponents, but pros and cons were weighed, and the decision was made.

There were some growing pains. The window for command selection moved left (earlier), sometimes so far that department heads were being considered before starting their second tours. Some of my friends who executed the early phases of the plan reported feeling burned out after a strenuous XO tour—and then they took just a week of leave before shouldering the responsibility of command at sea. I clearly recall, after 15 months as an executive officer, that I was mentally and physically spent. Having left it all on the field, I was thankful for the opportunity to attend the Naval War College before going to command. This period also gave me a chance to reflect on the lessons, failures, and successes of my XO tour and to better prepare myself for the next step. Having not yet screened for command was—at least in part—a motivator for me to give 110 percent as an XO. Contrast this with today’s XO in a fleet-up billet who screened for command long ago and, although there is a formal approval process, is all but assured of command at sea barring a significant mistake or failure of leadership.

My peers and I also had the opportunity to serve under two commanding officers—who, in my case, were as about as different as two people can be—and to learn from both. Fleet-up executive officers serve their entire tours under a single commanding officer, limiting exposure and experience. It is plausible that, over time, common flaws or stark contrasts between the two officers could amplify negative traits. It also seems possible that if a commanding officer has leadership issues, a fleet-up XO may be reticent to go outside the lifelines with concerns for fear of being seen as “sawing on the boss’s chair leg” in attempt to accelerate turnover. Loyalty to a CO is a key trait in an XO, but in the rare case of an overbearing, overconfident, or incompetent CO, the fleet-up XO, who depends on a positive recommendation to proceed to command, is in an awkward position.

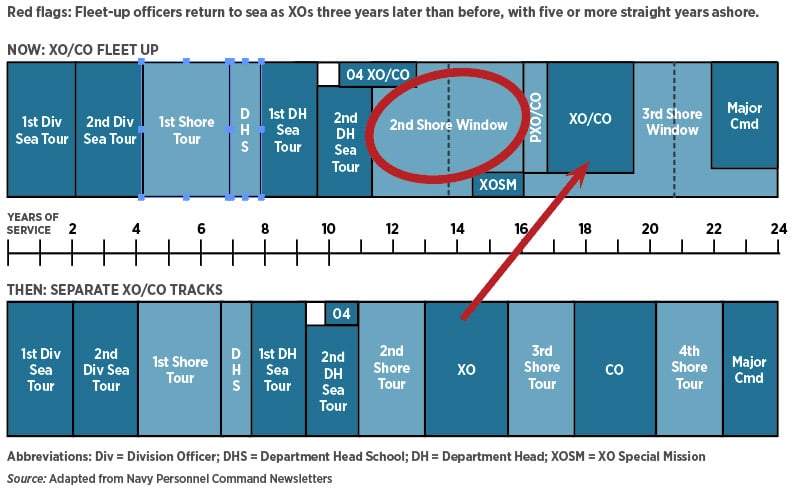

The fleet-up plan was successful in its intent. Under the new program, following a department head tour, officers could expect enough time ashore to complete two tours, such as the Naval Postgraduate School and a full 36-month joint tour. Officers who succeeded at sea were now meeting the career requirements to screen for flag at an earlier point in their careers—but at what cost?

Some of my friends serving their joint tours at Air Force or Army commands such as U.S. Northern Command joked that they practically forgot they were in the Navy, and therein lies the rub. Under the previous SWO career path, it was typical for a surface warfare officer to alternate between shore and sea at intervals of two to three years. This rhythm of “sets and reps” resulted in a balance between sea and shore, ensuring sufficient time to develop the standard “10,000 hours of experiential learning” required to become an expert mariner and an expert warfighter, and allowing enough time between sea tours to recover and reflect, but not so much as to allow the maritime edge to dull. Under the fleet-up plan, the interval between department head and executive officer sea tours—excluding pipeline training—can easily exceed five years, in some cases as many as seven years. This is too long. Despite the fleet-up plan being a good fit in other communities, the unique nature of command at sea warrants a different approach.

Layered Effects

As in all complex issues, there are other exacerbating factors. Nearly 15 years ago, the surface community decided to eliminate the Basic Division Officer Course at Surface Warfare Officers School (SWOS), replacing it with personnel qualification standards, on-the-job training, and the infamous “SWOS in a Box.” This decision eventually was seen as detrimental to SWO junior officer training, and a basic indoctrination course was established after about six years, but that generation of primarily computer-trained officers is now serving at sea as department heads—do they have the required experience to do their jobs? Two excellent 2009 Proceedings articles by Navy Lieutenants Mitch McGuffie and Padraic McDermott explored this possibility.1

An additional factor could be the shift to an Optimized Fleet Response Plan (OFRP). By shifting the operational cycle to 36 months from 27 months, the Navy extended the time between deployments, perhaps reducing the overall time spent at sea for everyone from division officers through department heads.

It also is worth remembering that for most fleet-up officers, this is their first time in command. I was privileged to have two opportunities, one as a commander and one as a captain. Recently I was asked what the primary difference was between my tours, and I had a ready answer: In my major command, I was more likely to say no if asked to do too much or take too much risk. I also was more cognizant of the gap between what I knew and what I thought I knew. With the level of competition in a destroyer or amphibious squadron, aggressive shiphandling and signing up for extra missions can be a discriminator for a new commanding officer; the second time around, the sense of urgency and the need to prove oneself are less compelling.

To be fair, some adjustments have been made to the XO/CO fleet-up program. Recognizing that the XO tour is incredibly draining, the Navy has inserted an operational pause to allow for 30 days leave, additional tactical training, and a reset period for SWOs to hone command skills and to provide some degree of leveling—sharing best practices and lessons learned with other XOs at SWOS—before they proceed to command. This is an improvement, but it does not mitigate the long interval between department head and executive officer, nor does it give future COs the opportunity to serve as XO for more than one commanding officer.

Another side-effect of OFRP is that each officer will complete a single 36-month cycle, seeing each phase of the deployment cycle only once, with no opportunity to roll the lessons of a deployment as an XO into a later command tour. You are always doing something for the first time—the exposure an officer would get from multiple tours on multiple ships is different from when you jump on one ship and go through one cycle.

Many senior officers, however, point out significant benefits that may be attributable to the fleet-up program. Some noted they have seen upticks in ships’ performance soon after fleet-up occurred. Others noted that the XO gets to know the crew and vice versa, and thus is better prepared to lead that crew as the commanding officer, and that the relative seniority of the executive officer under this program makes for a stronger command team. These are all very valid and important considerations, and the issue is sure to be debated at many levels, but reliable cause-and-effect data is difficult to come by. There are myriad possible causal factors for recent Navy ship collisions, such as reliance on technology, fatigue, or technical acumen. One impulse may be to focus on the SWOS pipeline, but that process improved dramatically following the USS Porter (DDG-78) collision, and training is only as good as the student’s receptiveness and the command environment that fosters it.

The idea that certain skills are perishable is not new to the Navy. Pilots must maintain proficiency with a certain number of flight hours per month even between flying tours, and nuclear officers are well aware of the “nuclear clock” that ticks out every five years and drives officers back to a nuclear tour or a mandatory refresher course. Such policies would be difficult for a SWO, and a five-year limit would undo some of the benefits of the fleet-up program, but perhaps these ideas are worth considering. Other possible options would be to cross-deck more XOs to COs of other ships of the same class, or to require returning prospective executive officers to complete a short stint at sea before returning to SWOS.

More exposure to command-served officers—from staff or the nearby war college—during each SWOS session (division officer, department head, surface command course) in a maritime mentoring format also would pay dividends. I was a bit taken aback when I applied to one of the commercial cruise lines after retirement and learned my Navy experience was inadequate for any senior seagoing position because I lacked formal U.S. Coast Guard mariner certifications. It might make sense to reinvigorate past efforts to align the SWO pipeline with the maritime certification process so that the SWO pipeline ensures officers become true “certified professional mariners.”

Ending the fleet-up process may not be the answer, but perhaps the program could build on recent improvements by mitigating the excessive time spent away from ships and producing true certified mariners. Would this process cost more time and money? Yes. But would it be worth it? One could argue that the Navy cannot afford not to.

‘He Must, Of Course, Be a Capable Mariner’

John Paul Jones said it best; at the end of the day, ours is a maritime profession. The only way to get good at driving ships is by driving ships—the more, the better. The plan to give the Navy more flag-eligible officers, while successful in that goal, did a disservice to our SWO commanding officers and their ships by not giving them the best chance of success at sea, where it counts. The point papers that produced the XO/CO fleet-up plan surely included such talking points as “faster promotion,” “increased joint opportunity,” and “higher flag selection rates.” It seems unlikely that there was one that said “Produce better mariners.” One hopes that for any revisions going forward, this will be the first bullet.

Captain Cordle retired from the Navy in 2013 after 30 years of service. His active-duty assignments included director of manpower and personnel for Commander, Naval Surface Forces Atlantic, and command of the USS Oscar Austin (DDG-79) and USS San Jacinto (CG-56). He is the 2010 recipient of the U.S. Navy League’s Captain John Paul Jones Award for Inspirational Leadership.