The term “lethality” can be associated with any number of things in the Navy. Oftentimes it will be associated with a weapon system, such as those found on a naval aircraft, surface combatants, or submarines. But how often are our personnel associated with lethality?

Warfighters are the core of the Navy’s combat effectiveness, but the current systems in place do not provide the most efficient or effective means of training them. Warfighters and their associated lethality could be improved by restructuring the commands responsible for pre-deployment training and staffing those commands with the right personnel.

The Current Conditions

In its current form, Navy units receive training from a variety of sources before proceeding to the integrated training phase, known as the Composite Training Unit Exercise (CompTUEx). This month-long exercise is designed to hone warfighters’ skills against a peer-level threat.

Unfortunately, most units spend time during CompTUEx attempting to finish training requirements that should have been completed during the basic phase of training, often because of longer-than-expected maintenance periods that come as a result of increased Global Combatant Commander (GCC) requirements. The Optimized Fleet Response Plan (OFRP) was designed to remove the ambiguity of maintenance periods for surface combatants and aircraft carriers. Since its implementation in 2013, OFRP has made some positive strides, but it will take additional time to witness its full effect on fleet readiness.

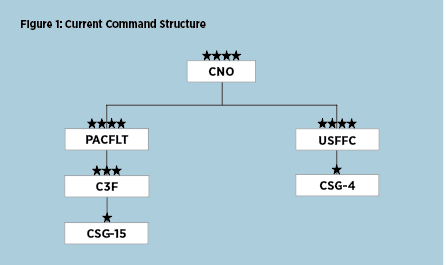

When deploying strike groups arrive for CompTUEx on either the West or East Coast, trainers from Carrier Strike Group 15 (CSG-15) or Carrier Strike Group 4 (CSG-4) will embark. These two commands are responsible for conducting the integrated phase of training and for recommending a deployment certification at its completion. On the West Coast, CSG-15 falls under the authority of 3rd Fleet (C3F) while on the East Coast, CSG-4 is under U.S. Fleet Forces Command (USFFC). This disparity in reporting produces differences between Atlantic and Pacific fleet training and is complicated by the fact that CSG-15 has a staff roughly one-third the size of CSG-4. Until recently, the commanders of these organizations had not previously served as CSG commanders. In fact, because of the billet structure at these commands, the personnel assigned in many cases never have performed the functions of those they are expected to train, mentor, and assess. These conditions have produced a culture that removes focus from the warfighter, prioritizes readiness reporting instead of training, and is absent the credibility that only experience can provide. Fortunately, it does not have to remain this way.

A Model that Works

Naval aviation has been using a model that has evolved and improved consistently since the inception and commissioning of the Navy Fighter Weapons School (TopGun) in 1969. Naval aviation has a representative weapons school for each of its communities under the umbrella of the Naval Aviation Warfighting Development Center (NAWDC) located at Naval Air Station Fallon, Nevada. Recognizing the benefits of this model, Naval Surface Forces and Submarine Forces have followed suit with the creation of the Naval Surface and Mine Warfighting Development Center (NSMWDC) and the Undersea Warfighting Development Center (UWDC).

Each warfighting development center (WDC) produces weapons tactics instructor (WTI) graduates who make their way back to the fleet armed with the most up-to-date tactical knowledge. At the same time, the WDCs retain graduates on their staffs to ensure that warfighter standardization exists throughout the community. As the threat evolves, the WDCs are able to craft new tactics and promulgate them to the fleet with the understanding that resident WTIs in ships, squadrons, and submarines will be the point of contact for any questions. Effectively, a network of professional warfighters has been established to infuse expertise and tactical standards throughout the fleet.

What about integration?

While this model works well for the individual units, it does not address warfighting at the composite warfare commander level, which is the focus of CompTUEx. Some mistakes are unavoidable and are to be expected when units begin working together for the first time, but most could be avoided by applying the WDC model to the integrated phase of training. This would include standardization among deploying CSGs, providing CSG-level tactical recommendations, and retaining WTI graduates on pre-deployment training command staffs to ensure standardization across strike groups and between fleets. While it is understood that CSGs that deploy in support of different GCCs have different requirements, standardization would reduce the amount of time and resources currently wasted repeating the mistakes of others.

Current Command Structure

Before any changes can be proposed, the current command structure must be understood. This command relationship is depicted in Figure 1.

The extra layer of reporting between Commander, Pacific Fleet (PacFlt) and CSG-15 does not lend itself to the same efficiencies enjoyed by CSG-4 and USFFC. Because CSG-15 operates with a staff roughly one-third the size of CSG-4, this training increases the strain on its personnel and reduces its effectiveness as an organization. These training strike groups need individuals who have completed a tour in the specific warfare area which they are responsible for training, mentoring, and assessing. For example, a former air wing commander should be assigned as the head of strike warfare training, or a former destroyer squadron commander should be assigned as head of the sea combat training.

The difficulty lies in finding highly qualified post-major command individuals and detailing them to commands in this capacity. CSG-15 and CSG-4 need knowledgeable and experienced war-

fighters who can mentor, train, and assess the fleet to provide an overall increase in fleet lethality. Qualified individuals may not be available to fill these roles, and if that is the case, perhaps the best place from which to draw personnel to fill these billets is from the WDCs.

Proposed Command Structure Changes

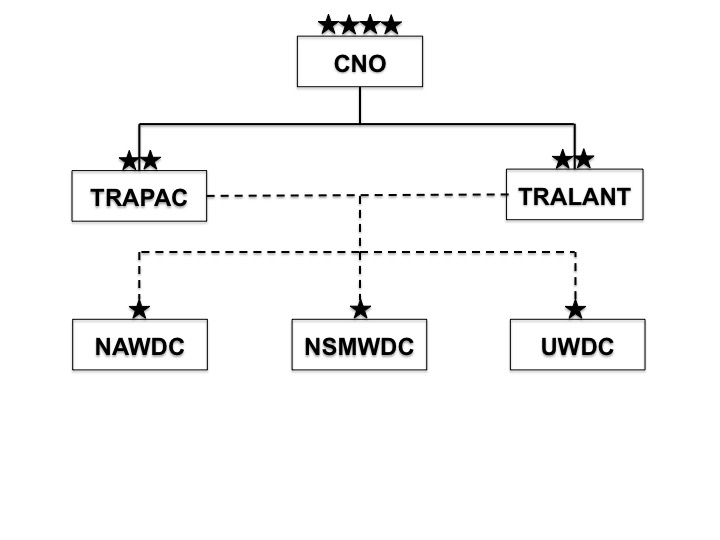

To enhance the capabilities and mission of CSG-15 and CSG-4, their naming convention needs to change. Calling these commands “carrier strike groups” is a misnomer. The mission of these commands is to provide integrated warfare commander- and composite warfare commander (CWC)-level training, mentorship, and assessment for deploying strike groups. As such, the commanders, and their entire staffs, should be senior to those they are tasked to train, mentor, and assess. These two commands should be called Training Pacific (TraPac) for CSG-15, and Training Atlantic (TraLant) for CSG-4.

On the West Coast, the extra layer of C3F between the proposed TraPac and PacFlt should be eliminated to streamline efficiency and reporting. This would remove the current ambiguity between the coasts, allow better coordination between TraPac and TraLant, and increase the efficiency and effectiveness of the training provided by these commands. As a bonus, C3F could shed the administrative burden of CSG-15 (TraPac), allowing C3F to focus more on managing operations under the 3rd Fleet Forward concept.

The last and most important proposed change to the command structure would be the addition of a tactical control (TaCon) relationship between TraPac, TraLant, and the WDCs, which would allow PacFlt and USFF the ability to direct TraPac and TraLant to conduct and support pre-deployment training and certification. After units deploy, any deficiencies noted by the GCCs could be directed to PacFlt and USFF who could then directly task TraPac and TraLant with correcting them. Changes to training based on mission requirements could be identified and directed from the beginning of the pre-deployment training cycle. This is an advantage over the current system, which can allow deficiencies to remain unchecked until a unit arrives for the integrated phase of training. With the ability of TraPac and TraLant to direct the sources of unit training, changes could be incorporated at the lowest possible level, such as Afloat Training Group (ATG). This streamlined process not only would provide better unit level training, but also would ensure the maximum efficiency and effectiveness of training during the integrated phase.

Figure 2 depicts the proposed command structure changes and the TaCon relationship between the proposed TraPac, TraLant, and the WDCs.

A Way Ahead

These suggestions are simple and would require minimal resources to accomplish. Once implemented, the savings in time, resources, and the associated increase in fleet lethality have the potential to be significant. The Navy continually must procure the best weapon systems to solidify its advantage. But, if the true weapon systems—the warfighters—are not emphasized, the overall lethality of the fleet will decline rather than improve. These proposals will put improved focus on Navy warfare commanders and strike group commanders and should improve the overall lethality of the fleet.

Lieutenant Commander Reddick is an F/A-18 pilot. He has previously served in VFA-151, on the staff at the Naval Aviation Warfighting Development Center (NAWDC), and at Carrier Strike Group 15 (CSG-15). He currently is serving in VFA-195 as a part of Forward Deployed Naval Forces Japan.