A Mistake Should Not Kill a Sailor’s Career

(See E. Heck, p. 14, December 2017

Proceedings)

Prepare for the “To Be Or to Do” Moment

(See R. Schuhart, pp. 10-11, December 2017 Proceedings)

As a judge advocate who has served inter alia as trial counsel, defense counsel, and staff judge advocate, I was extraordinarily impressed with Petty Officer Third Class Elizabeth Heck’s candor and wisdom. Too often, officers and noncommissioned officers have a horrible zero-defect mindset that is especially manifest in those “company men” of whom Commander Schuhart spoke within three pages of Petty Officer Heck’s contribution. When I joined the military, it was not uncommon for command sergeant majors (E-9s) in the 82nd Airborne Division to tell me, “Yeah, I made sergeant [E-5] three times!” And when I look back at the leadership qualities of those men, many with Silver Stars from Vietnam, it saddens me to think that today our military may be losing such colorful, valorous individuals.

Petty Officer Heck’s article ought to mandatory reading at every JAG school, as it justly brings compassion and humanity to the law.

—Lieutenant Colonel David G. Bolgiano, U.S. Air Force (Retired)

I share Petty Officer Heck’s concerns and recommendations. She has overcome a tremendous disadvantage and appears to be an extremely sharp, perceptive sailor. It was unfortunate that her chain of command was not allowed to weigh in with its positive recommendation at her nonjudicial punishment (NJP).

In the mid ’70s, as a combined A (auxiliary) and R (repair) junior division officer on the USS California (CGN-36), I was involved in the NJP of a young third-class machinery repair petty officer (MR3). My MR3 had had a run-in with the shore patrol while on liberty and had been placed on report. His work control center supervisor, the division leading CPO, and I all recognized his value to the division, the ship, and the Navy. In a pre-mast consultation with the ship’s executive officer, Commander Fred Triggs, the command master chief, and the engineer officer, John Pearson, we agreed to recommend that the MR3 be awarded a “suspended bust” to E-3, MRFN.

Our commanding officer (CO), Captain Floyd “Hoss” Miller, accepted our recommendation at mast and gave our MR3 the chewing out he deserved. He was awarded the six-month suspended bust to MRFN, loss of liberty, and a fine.

his was a tremendous learning experience for me on the management of the Navy’s largest asset, our sailors. The net result of this experience was that our MRFN turned into a model sailor, had no further mishaps, and was fully restored to MR3 after his probationary six months. If I recall correctly, he was advanced to MR2 and was an exceptional leader in the “R” half of the A/R division when I was transferred off the ship some time later.

—Captain Ron Scudder, U.S. Naval Reserve (Retired)

In a growing Navy, I think more opportunity will be afforded to those with early failures. We’ve always said we’re not a zero-defect Navy, but when you have room for only one and two are nearly identical—the one with the slip is “usually” the one that loses.

Accountability can be a very powerful tool to build leaders, provided that after punishment come rehabilitation and remediation. Among my peers, some have accepted the punishment and then sought to again prove themselves to the organization; they ended up as senior enlisted.

I have observed that sailors often tend to feel, after paying the appropriate price and learning the lesson, that the punishment should end. But accountability means not only accepting responsibility for one’s misdeeds, it also means accepting and serving out the penalty. This may be “45/45,” half a month’s pay times two, or a reduction in rate. It is up to the CO, right or not, to decide. Just as with maximum sentences for crimes, the judge may not impose them all but that is a possible outcome. Sailors should not feel wronged.

—Fleet Command Master Chief Russell Smith, Manpower, Personnel, Training & Education (N-1)

Can’t Kill Enough to Win? Think Again

(See D. G. Bolgiano and John T. Taylor, pp. 18−23, December 2017 Proceedings)

It is alarming that two senior officers, Lieutenant Colonels Bolgiano and Taylor, cannot differentiate between the total war environment of World War II and the ongoing jihadist insurgencies we’re mired in today.

In the former we were opposed by unified nation states with defined borders and entire populations fully dedicated to the war aims of their governments. The nations became our targets. Today we are opposed by fragmented ethnic groups and transnational religious zealots who generally are lacking in national identity. Just who is it we should be killing in ever-greater numbers? Should we have carpet-bombed the imprisoned citizens of Raqqa because ISIS was there? Should we wait for the Taliban to form up into regimental-size formations so we can bring to bear our most lethal weaponry? As simple, and perhaps satisfying as it might be, our current enemies are not going to allow us to re-fight World War II.

Aside from simplifying the rules of engagement and lightening up on the role of JAG officers in strike planning, both useful changes, the authors offer little by way of new ideas. Until our enemies present us with suitable targets—and let’s be honest, they probably won’t—I have to agree with Admiral Mullen. We’re not going to kill our way out.

—Captain David Scott, U.S. Navy

Reserve (Retired)

Revamp FitReps for

Lethality

(See B. Cordial, pp. 24-29, December 2017 Proceedings)

While I salute Lieutenant Cordial for thinking “out of the box” about revamping a tired old system for rating officers, I’m not sure that Sabrematics is the right model to follow for the future. Seems to me that it’s too much in the wrong direction.

Recent events reiterate that we are still measuring the wrong things when it comes to scoring officers. We’re making it about management and technical skills, when it fundamentally is about leadership: what it is, how to measure it, and how to rate officers in how well they understand and practice it. We want leaders who can command.

So the first major change we need in our FitRep system is to start asking penetrating questions to assess our officers’ ability to lead. For example, we must probe their good character, and we need to force seniors to provide hard examples to support their leadership assessments. We must inquire about junior officers’ intuition and demonstrate that we can correctly rate their ability to face amorphous situations. Do they sense when a bridge team (or a ship) is not ready for its mission, and do they know how to take action to fix it? Do they have a vision, can they take charge in a crisis, and have they demonstrated those skills? And do they understand how to motivate and guide a team? There’s much to leadership, and the Navy must begin by focusing on this crucial skill in any new FitRep format.

—Captain Chris Johnson, U.S. Navy (Retired)

She’s a Warrior

(See S. Brugler, pp. 66-67, November 2017; and J. A. Stout, p. 8, December 2017 Proceedings)

In her pithy article, Commander Brugler provides a solid response to the points made in Secretary James Webb’s 1979 article, as well as his potential personal conflict with future political employment. She also attempts to describe a perceived changing character of war (technological advances) during the past 40 years as a way of shooting down Webb’s assertion that combat-leadership preparation degraded after admitting women to leadership roles.

Given Commander Brugler’s assertions on the changing character of war and steady accomplishments by women in the naval services since 1975, it seems that we, as a department, should continue to align with this model and do away with our archaic physical-fitness differentiations based on one’s sex. Why must there be a different run time or pushup minimum for men and women of the same age when it comes to combat readiness? Given the added complexity of transgender integration with regard to physical-readiness-test standards, baselining our force to one standard, regardless of sex, would definitely support Commander Brugler’s main hypothesis and theoretically would eliminate all discussions of any inabilities for combat. It would be either pass or fail.

—Commander A. J. Kruppa, U.S. Navy

Commander Brugler’s essay contained one error. Women were first admitted to the U.S. Merchant Marine Academy, not the Coast Guard Academy, a year before entering the other service academies. At a meeting of representatives of all service academies in the spring of 1976, the Merchant Marine representative, a captain in the Naval Reserve and the only woman at the conference table, shared their plans and experiences to the great benefit of the Naval Academy.

—Rear Admiral W. J. Holland Jr., U.S. Navy (Retired), in 1976 Project Officer for the Entrance of Women to the Naval Academy

On Board the USS Macon Going Down

(See A. D. Clift, p. 92, December 2017 Proceedings)

I read with great interest Mr. Clift’s article about the crash in 1933 of the Macon (ZRS-5) and how senior aviator Miller became the last man ever to hook up an aircraft to a U.S. Navy rigid airship. It was particularly interesting to me because my father, Lieutenant A. W. Gorton, naval aviator 1720, was the first. In 1929, he hooked up on the USS Los Angeles (ZR-3) during the Cleveland air races. Upon being hoisted up to the airship, Lieutenant C. M. Bolster transferred to the front cockpit of the Vought UO-1, they unhooked, and landed at the Cleveland airport. Thereby, Lieutenant Bolster became the first person to change from an airship to an airplane in the air.

—MG William A. Gorton, U.S. Air Force (Retired)

Where Are You Going, Kings Point?

(See T. F. McCaffery, pp. 56−60, November 2017 Proceedings)

Commander McCaffery provides an accurate and informative summary of the history and current status of Kings Point. I am with his analysis right up to his conclusions. Unfortunately (for proud graduates of Kings Point), we no longer need buggy whips, and we no longer need a federal service academy to supply officers for the U.S. Merchant Service.

The U.S. flag fleet has decreased dramatically. The number of officers needed to man (or woman) that fleet has declined equally. The existing and forecast needs of the merchant service can easily be met with graduates of the six state maritime academies—California State University Maritime Academy, Great Lakes Maritime Academy, Maine Maritime Academy, Massachusetts Maritime Academy, State University of New York Maritime College, Texas A&M Maritime Academy—and Seattle Maritime Academy, although I suspect not all of them are needed either.

If it is determined that a federal merchant officer training source needs to be maintained, the U.S. Coast Guard Academy (my alma mater) easily could fill that role, either by requiring that all graduates earn a third mate’s or third engineer’s license as a prerequisite to graduation (as I have long advocated) or by creating a merchant “major” in which cadets who volunteered for that track would earn their licenses and be commissioned as Coast Guard Reserve officers.

The sale of that valuable Long Island real estate occupied by the U.S. Merchant Marine Academy would make a nice contribution to the U.S. Treasury.

— Captain Paul J. Prokop, U.S. Coast Guard (Retired)

November Cover

(See November 2017 Proceedings)

As a retired sailor and longtime Naval Institute member (now a Life Member), I look forward to and get great enjoyment and professional enrichment from reading Proceedings each month. It keeps me abreast of world military affairs and gives me a different perspective on ongoing events around the globe. Congratulations on a great publication and a diverse forum where opinions from all ranks and stations are encouraged without prejudice.

One small matter, though, I think should be brought to your attention. The cover of the November issue shows a U.S. Marine in combat attire. The caption on page 1 says that he is participating in “Exercise Talisman Saber 17 in Austria.” As you would no doubt be aware, however, Talisman Saber (also spelled Sabre in Australia) is a biennial joint Australian-U.S. military exercise involving the Australian Defence Force and the U.S. military across six locations in northern and central Australia; the Coral Sea; Honolulu; Denver, Colo.; and Suffolk, Va. Most of the exercises are concentrated at the Shoalwater Bay Military Training Area and other locations in northern and central Australia, and in Australia’s territorial sea and exclusive economic zone. I mention this erroneous caption merely to ensure accuracy and in no way intend any disrespect. I am sure that the inclusion of Austria is just a typographical error.

—Chief Petty Officer Stevan A. Coll, Royal Australian Navy (Retired), Medal of the Order of Australia

Rebuild Air ASW

(See N. Woodworth, pp. 32−36, October 2017; and A. Lennon, pp. 8−9, December 2017 Proceedings)

Commander Wooworth clearly articulates the need for improved ASW training by citing the growing submarine threat and the atrophy of ASW knowledge and skills of nearly a full generation of patrol squadron (VP) aircrew primarily deploying to “the desert” to support overland operations. His case is compelling, and the “Red Dolphin” adversary diesel-submarine squadron idea is both innovative and based on a historically proven concept (“Red Eagles” Tactical Air [Tac-Air] training during and after the Vietnam War). He also correctly identifies the “most pressing” challenge as cost. Yet when offering solutions, he neglects to consider the Navy’s own organic, part-time force as a cost-saving asset: its Navy Reserve.

To keep costs down, Woodworth recommends manning the adversary diesel submarines with contractors and supplementing underway periods with a military detachment of instructors. The operating model he proposes is ideally suited to capitalize on Reserve capabilities. The boats could be crewed by a minimal compliment of active-duty and/or full-time support sailors, enough to get under way for short-notice training missions and be supplemented with Selected Reserve sailors for planned exercises. This construct would not only keep the operating costs down, it also would provide several other efficiencies and benefits, such as:

• Recapturing the Navy’s investment in training active-duty submarine sailors who decide to separate at the end of their obligations by keeping them in the Reserve (currently there is no structured opportunity for Reserve submarine sailors to go to sea). This likely would entice more of them to affiliate with the Navy Reserve, thereby increasing the Navy’s return on investment by retaining their training and experience.

• Keeping manpower costs to a minimum, because the model would not require much more than the standard 38 days per year that Selected Reserve sailors already provide.

• Manning the boats with uniformed personnel would provide more flexibility and avoid the added cost and liability burden for benefits such as life insurance, which is required for contractors to operate in a hazardous-duty assignment. Additionally, uniformed personnel would provide true mil-to-mil engagement to build partnerships if the Personnel Exchange Program were offered.

• Allowing for continuity of training and experience in the ASW mission (Reserve sailors can serve 20-plus years in a squadron/unit developing decades of knowledge and experience that can provide stability through up/down cycles of opportunity, thereby preventing a “brain drain” effect.)

• Providing strategic depth if and when greater ASW capacity is needed. Unlike civilians, Reserve sailors can surge (mobilize) in a crisis, and the sailors in this construct would be intimately familiar with diesel-submarine tactics as well as being relatively current in submarine seamanship.

Using a combination of active-duty and Reserve sailors (and international partners) to support the renewed ASW training effort would not only be cost-effective, it would also strengthen our total Navy team and enable us to truly “train like we fight.”

—Captain Derek Wessman and Captain

Michael Steffen, U.S. Navy

It’s Time for Concealed Carry-on Bases

(See C. R. Whipps, p. 10, November 2017 Proceedings)

Our country is awash in handguns and assault weapons. Gun violence is a daily occurrence, with more people killed by guns than die in automobile accidents. Many jobs on our bases require the carrying of weapons that rarely are concealed, but even with the presence of these people, trained and skilled in the use of weapons, accidental shootings occur.

Many use the Constitution’s Second Amendment to explain their desire for a concealed weapon. But they really are replacing their lack of self-confidence and boosting their egos. There are also many, even though highly educated, who are just Second Amendment radicals. They have met all the requirements, yet remain irresponsible gun owners. To suggest that concealed carry will reduce sexual assault is a lack of understanding of how sexual assault occurs.

I have guns that I use to hunt and target shoot in a responsible way. Concealed carry on base is irresponsible, dangerous, and will add to unintentional shootings. OpNavInst 5530. 14 E in no way infringes on one’s Second Amendment rights.

—James Sandison, retired Naval Sea Systems Command engineer

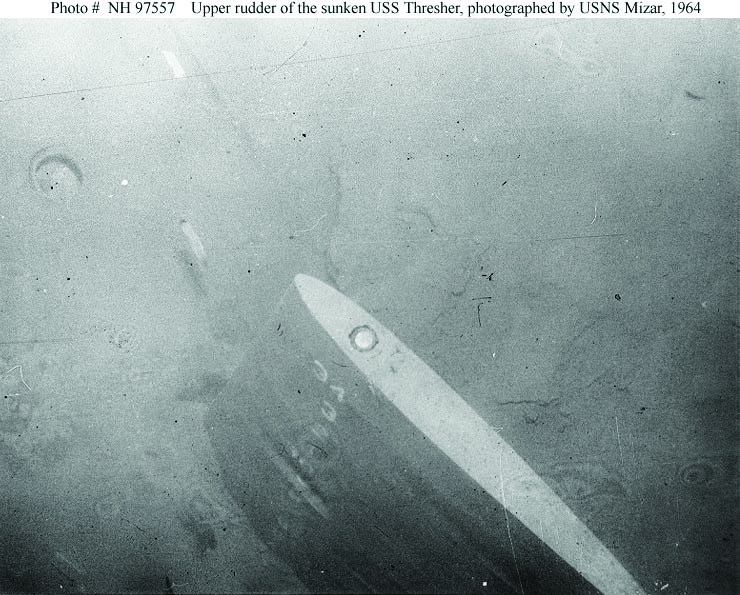

Unraveling the Thresher’s Story

(See J. Yurso, pp. 38−42, October 2017 Proceedings)

I was new-construction E&RC division officer on the Thresher (SSN-593) and the co-coordinator for our shock trials in Key West and for the PSA seawater piping systems hydrostatic tests. Subsequently I was CO of a nuclear-attack boat and SubPac senior PCO instructor.

After the event, Nuclear Reactors came to the USS Hamilton (SSBN-617) because it had an S5W plant, and because I was engineer there, and the only extant officer with intimate knowledge of the Thresher, the details of the shock trials, and the post-shakedown availability (PSA) testing. At that time, HGR’s electrical and piping/systems guy (Carl Swenson) and reactor design chief, Brodsky, on the back of an envelope, with me as the engineering officer of the watch under their direction, over a period of several hours and several fits and starts, developed the fast scram recovery procedure. The reactor plant manuals were then modified to include these procedures, and all present in-port and in-Continental United States nuclear engineers were ordered to Washington, DC, where I lectured/tutored them on the new procedures.

There is no way that anyone on the Thresher at the time of her loss would have known, dreamed of, or thought of how to save the power plant. The author of the article is far off-base there. Although a knowledgeable nuclear-power school instructor, Lieutenant Raymond McCoole was as-yet unqualified on the Thresher and had no experience whatsoever on the S5W power plant. Even if time had permitted, his presence would have been of no practical value.

However, none of that makes any difference. The fact is that there was not enough response time to counter the effects of serious flooding, no matter how much knowledge and experience were available. With the plant in a post-scram scenario, even with exceptional plant experience and knowledge, on-the-spot improvisation of reactor operation would not have come to mind. Lieutenant McCoole was just fortunate to have not been on board.

The author thought more training would have perhaps let the crew save the ship, but in fact many of the men who went down with the ship were the same who had conducted the shock trials, both officers and crewmen. No choreographed casualty training could have come close to replicating that which we received during said trials. We had failed sil-braised joints spraying seawater in all directions, tripped power breakers shutting down needed equipment, broken airlines creating deafening noises and misting the atmosphere with fog and insulation. This was combined with the bone-rattling nearby explosions that were powerful enough to cause all that and also unship our snorkel mast, force partially open our reactor compartment access door, and cause the torpedo tube inner doors to orbit inside their locking rings. Yet the crew handled all this with aplomb.

There was little crew turnover during the PSA. New members would not as yet have been qualified to stand power plant watches; hence, that shock trial experienced team would have been manning all relevant stations.

As to the availability of plant and electrical knowledge, upon which the author seems to believe a bright lieutenant, although unqualified on both ship and power plant, could improve: the most knowledgeable man about such matters I have ever known, besides HGR’s electrical chief, was EMCM(SS) Ben Shafer. It was both a privilege and a wonderful learning opportunity to serve with him. I took every possible opportunity to sit with him and learn from him. His knowledge of how every kind of electrical component and our S5W systems as a whole worked was encyclopedic. I am reminded of JFK’s remark about the assemblage of brains at some of his White House dinners as opposed to when Thomas Jefferson dined alone.

What more could have been done? I believe two things. First, the sound trials themselves were a recipe for disaster: at test depth, turn everything off, then turn them on and off one by one to test their radiated sound. While the Thresher was apparently not yet at test depth when the casualty occurred, based on their penultimate UQC transmission, they were heading there. Actual depth at the time is not known. We did all that a few times during the earlier sound trials—dangerous; a safer testing process was needed. Second, and in this case most important, we should have cut into the sound cocoon to inspect for failed sil-braised joints hidden behind that complicated structure. Because of the difficulty of rebuilding it, none of us—neither ship nor shipyard—seriously considered doing that. But that is most probably where the failed seawater joint(s) were located.

—Captain Kenneth L. Highfill, U.S. Navy (Retired)