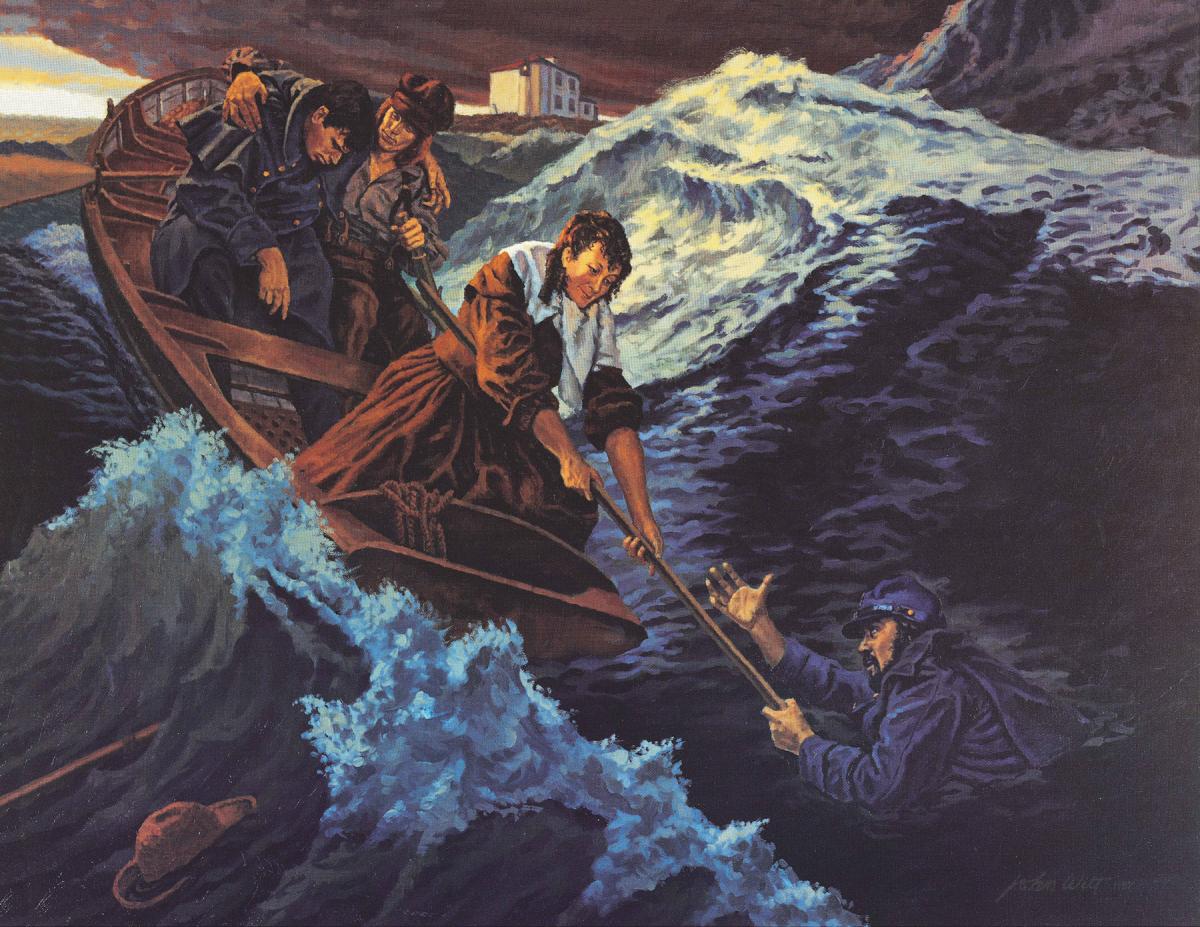

Women have played an important role in U.S. Coast Guard history. From the American Revolution to 1948, women served as assistant—in some cases, primary—lighthouse keepers. The first woman to serve was Hannah Thomas, who took her husband’s place when he joined the Army during the American Revolution. Ida Lewis served as unofficial and official keeper of Lime Rock Light in Newport, Rhode Island, from 1857 to 1911, and as keeper she was credited with saving 18 lives and named “The Bravest Woman in America” by the American Cross of Honor Society.

Women played an important role in the early Coast Guard. Ida Lewis served as unofficial and official keeper of Lime Rock Light in Newport, Rhode Island, from 1857 to 1911, and is credited with saving 18 lives, including the two soldiers dipicted here in a painting of her 1881 Gold Lifesaving Medal rescue. (Coast Guard Collection)

In the early 20th century, the role of women in the Coast Guard shifted.1 They served in World Wars I and II and the Korean conflict. After each of these wars, however, most women were released from service, and by 1956, there were only 12 female officers and nine enlisted women. Congress passed legislation in 1973, allowing women to serve alongside men on active duty, and by 15 January of the following year, the first female recruits arrived in Cape May, New Jersey. All but three of the recruits in that first all-female company graduated, and from that point forward all boot camp companies were mixed gender.

Throughout the ‘70s and ‘80s, women took command of cutters, became aviators, and served as crew members on high- and medium-endurance cutters. By the 1990s, women were serving in combat roles in the Persian Gulf as part of Operations Desert Storm and Desert Shield. While women have had a great impact and served meritoriously in the Coast Guard, the service currently is facing a serious retention problem when it comes to female enlisted service members.2

Because women leave the Coast Guard earlier in their careers than men, their representation in senior enlisted leadership positions is much smaller than that of men. More women in leadership positions could encourage women to consider longer careers in the service. (U.S. Coast Guard)

Low Retention of Women

Women make up approximately 14 percent of the enlisted workforce, which is up slightly from 2008 when they represented about 11.6 percent.3 There is strong female representation in the traditionally female-friendly ratings of yeoman, health services, and public affairs, and a decidedly smaller presence in the aviation survival technician, diver, and electronics technician ratings.

Current data, however, show that women are leaving the Coast Guard at a higher rate than their male shipmates in both the enlisted and officer ranks. Between one and ten years of service, the female enlisted attrition rate is 2–3 percent higher each year than that of their male counterparts, leading to an overall attrition rate 10–15 percent higher during that time. Women generally are leaving the Coast Guard between their fifth and tenth year of service, and by year ten, female retention is 40 percent. Because women are separating from the service early in their careers, there are fewer women in enlisted senior leadership positions. For example, in fiscal year 2015 (FY15), women made up 54 percent of yeoman third class members but only 39 percent of yeoman chiefs. The level of representation gets even smaller in more traditionally male ratings such as boatswain’s mate. In FY15, women made up 14 percent of boatswain’s mate third class members and only 3 percent of boatswain’s mate chiefs.4

Why Women Leave

Former Vice Commandant of the Coast Guard Vice Admiral Sally Brice-O’Hara and corroborating research suggests that family plays a big role in pulling women from the military. First, women tend to be the primary caregivers in many families, and in the absence of readily available and affordable child care, they may leave the military to take care of their families. Also, women might find it easier to sacrifice their military careers if they are married to another service member and colocation is hard, or if their civilian spouse does not have the flexibility to do regular permanent change-of-station moves.5

Two other factors that likely contribute to the higher attrition rate of enlisted women are the culture of the military and the lack of role models. The military is a very male-dominated profession. This can lead to double standards, gender discrimination, sexual harassment, and a belief among women that they are less than.

The lack of female role models for junior enlisted members is another issue. With significantly fewer women in enlisted leadership roles, younger female enlisted members have no female mentors to talk to, look up to, or be inspired by, which makes it difficult for them to envision a future within the organization. Men can mentor these women; however, they do not have the capacity to answer every woman-specific concern. Faced with a big enough problem, a woman may decide to leave the service if she does not have other women to coach or mentor her.6

The current trend in the female retention rate can lead to inequality, few women in leadership positions, high operational and financial costs, and a lack of diversity, which can lead to a less capable and less successful organization. Diversity is a powerful tool that can increase innovation, creativity, and productivity. An MIT study showed that a workforce evenly split between men and women could increase productivity by as much as 41 percent because of the greater social diversity and wealth of knowledge among workers.7 Women have much to offer as enlisted military leaders. Women tend to be more empathetic and better listeners, slow to show anger and quick to collaborate, and more likely to overperform to ensure acceptance and promote diversity.

Who Needs Women?

The Coast Guard needs women. The military needs women. So, how can the services fix the problem? The biggest issue to be addressed is the discord between the military and family. One solution could be more child development centers in locations where there is a large Coast Guard presence and incentives for in-home care programs in smaller locales. The service also could employ career counselors to mediate between service members and assignment officers; someone who can help members manage their careers and discuss critical issues before it is too late.

To increase the number of women in traditionally male-dominated ratings, the Coast Guard could start a targeted career development initiative to encourage women to join these ratings and support their success. Another solution would be not to assign women to a unit if there are not other women, including leaders and junior members, to serve as mentors and role models.8 Finally, the biggest solution would be communication and follow-through. Measure the command climate to make sure everyone feels they are being treated equally and hold people accountable if initiatives are not being implemented. Vice Admiral Brice-O’Hara noted, “Women are courageous and resilient because they have confronted and overcome tough circumstances.” This is just one more hurdle they must overcome.

1. Diana Sherbs, “The Long Blue Line: A Brief History of Women’s Service in the Coast Guard,” Coast Guard Compass, 16 March 2017.

2. Sherbs, “The Long Blue Line.”

3. Celina Ladyga, Jillian Lamb, Shannon McGuire, and Jon Ladyga, “Duty to People: Retaining Coast Guard Women,” master’s thesis, George Washington University, 2017.

4. Ladyga et al., “Duty to People.”

5. VADM Sally Brice-O’Hara, USCG (Ret.), “Women’s Retention in the Coast Guard,” e-mail interview by author, 19 April 2018.

6. Brice-O’Hara, “Women’s Retention in the Coast Guard.”

7. Peter Dizikes, “Study: Workplace Diversity Can Help the Bottom Line,” MIT News, 7 October 2007.

8. Brice-O’Hara, “Women’s Retention in the Coast Guard.”