You can kick this old service around, tear it to pieces, scream from the house-tops that it is worthless, ought to be abolished or transferred to the Navy, have the people in it fighting among themselves and working at cross purposes and it bobs up serenely bigger and stronger than ever.

Commander Russell R. Waesche, Sr., 1935

As Commander (later commandant) Waesche’s quote indicates, the evolution of the United States Coast Guard provides a truly unique study in organizational history. This year marks the 228th birthday of a service that has endured despite reorganizations and departmental transfers, and absorbing other federal maritime services along with their missions, personnel, offices and assets. Through it all, the Coast Guard has been shaped by national and world events, wars, and all sorts of maritime disasters that expanded the Service’s range and mission set. This year’s immediate response to hurricanes Harvey, Irma and Maria demonstrates that the Coast Guard’s motto, Semper Paratus-“Always Ready,” is appropriate now more than ever.

Congress established the Service’s original predecessor agency, the U.S. Revenue Cutter Service, in 1790 at the insistence of first Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton. Hamilton started this civilian law enforcement service with a fleet of 10 small sailing cutters, each one allocated to an East Coast seaport. A local customs collector oversaw each cutter’s operation and the collectors received their orders directly from the Secretary of Treasury. In addition to its original mission of law enforcement, the 1800s saw Congress assign to the Service the missions of search and rescue, naval defense and maritime interdiction. However, the Revenue Cutter Service remained a civilian agency that militarized only in time of war.

Within one hundred years of its founding, the Revenue Cutter Service began to develop a global reach. As the U.S. expanded from East Coast to Gulf Coast and on to the West Coast, revenue cutters populated regional seaports, such as New Orleans and San Francisco. By 1867, cutters were cruising Alaskan waters and the Spanish-American War sent them as far away as the Southwest Pacific. With the annexation of Hawaii in 1898, cutters began regular patrols in various parts of the Pacific. This territorial growth led to an increase in missions, including fisheries enforcement and humanitarian response. After the Titanic disaster, the Service also undertook the International Ice Patrol, which located dangerous icebergs afloat in navigable waters of the North Atlantic. By this time, the Service had established divisions to administer cutter operations, including New York, Eastern, North Pacific and South Pacific divisions. It would continue to use this division system well into the 1930s.

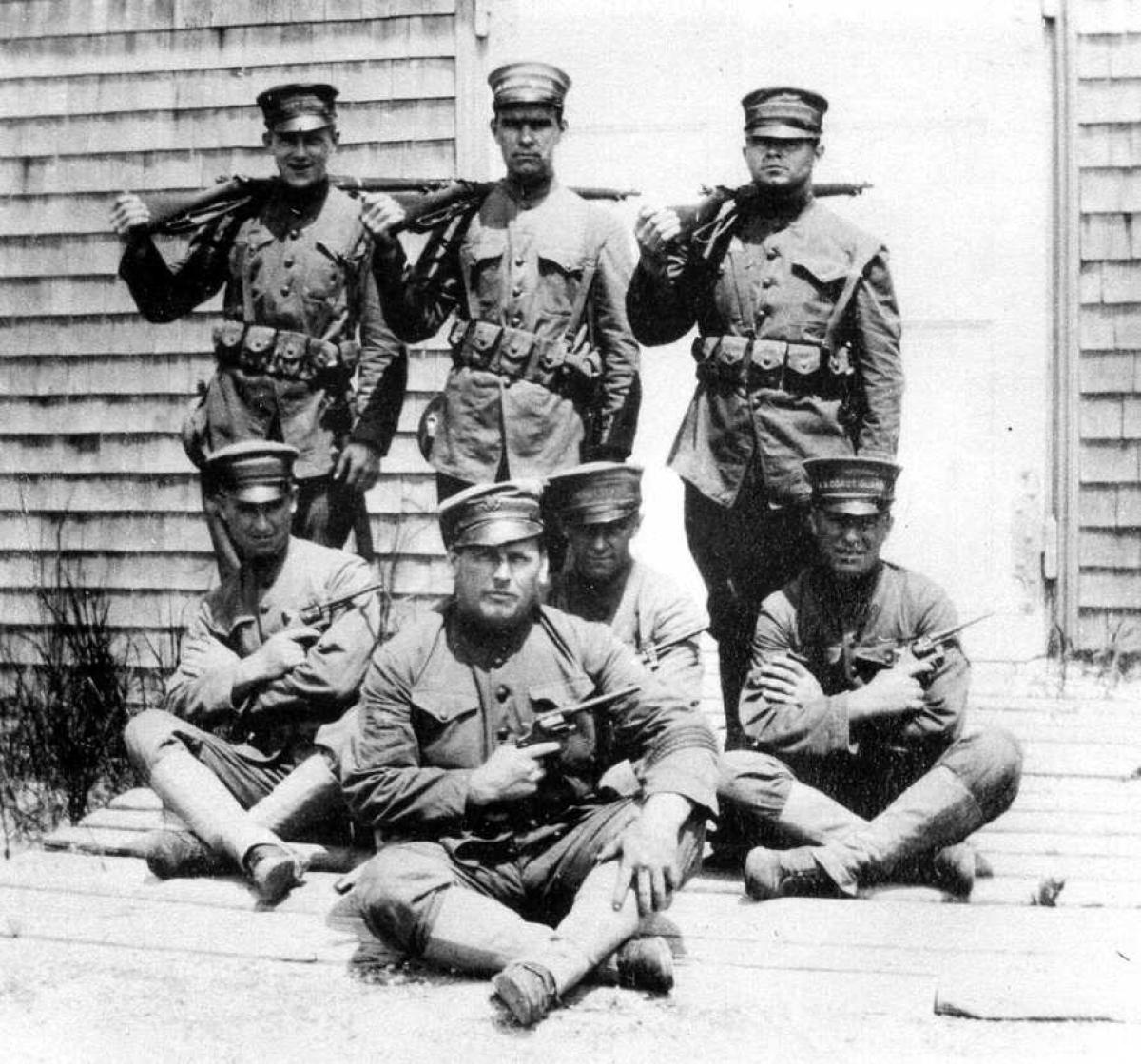

The second federal service that formed the Coast Guard was the U.S. Lifesaving Service. Established by Congress in 1878, the civilian-operated Lifesaving Service came under the leadership of Superintendent Sumner Kimball, who developed a nation-wide system of 12 districts to administer the Service’s boat stations, which numbered 183 by 1881. In 1915, President Woodrow Wilson merged the Lifesaving Service with the Revenue Cutter Service to form the U.S. Coast Guard. The merger brought together hundreds of smallcraft from the Lifesaving Service and numerous cutters operated by the Revenue Cutter Service. Kimball and ranking Revenue Cutter Service officer, Ellsworth Bertholf, engineered the combination of the two civilian agencies and Bertholf became first commandant of the new maritime service.

For years after the 1915 merger, the Lifesaving Service boat station district system and Revenue Cutter Service division system co-existed within the Coast Guard. It would take decades to unify the two systems into one organizational model. After becoming commandant, Bertholf wrote,

By evolutionary processes coincident with the steady growth of the Nation, additional duties were successively added to this service to meet the ever-increasing demands of the maritime interests in so far as they were connected with governmental functions . . . .

Bertholf’s message characterized the development of the Revenue Cutter Service before the merger; however, the Coast Guard continued to adopt new missions and “evolve” to meet the nation’s maritime needs. The newly formed Coast Guard had become not only the nation’s foremost search and rescue service, capable of coastal lifesaving operations and high seas rescues, but also an official U.S. military service. And, it remained a law enforcement agency, as it does today, even though it became a military service.

In World War I, the Treasury Department transferred control of the Coast Guard to the U.S. Navy. During the war, the Coast Guard carried out all of its military duties in the air, at sea and on land, and it adopted the important national security mission of port security. Meanwhile, it performed its normal missions of law enforcement, search and rescue and humanitarian response. The war also expanded the Coast Guard’s area of responsibility well beyond U.S. territorial waters. This new territory included the Atlantic and Pacific oceans and adjoining bodies of water, such as the Mediterranean Sea. After proving its worth as a branch of the U.S. military in wartime, the Coast Guard returned to its place within the Treasury Department.

The 1920s and early 1930s saw a postwar expansion and modernization of the Coast Guard. With enactment of the 18th Amendment, the Service became the lead law enforcement agency during Prohibition, increasing the Coast Guard’s size and technological sophistication. In this war against liquor smugglers, the Service operated 31 of the U.S. Navy’s four-stack destroyers and several new classes of cutters built for long-range offshore interdiction. Prohibition also saw permanent establishment of Coast Guard aviation and the founding of a Coast Guard Intelligence Office, which became a leading federal intelligence branch and helped break enemy codes in World War II. Fighting the Rum War proved the largest law enforcement effort in Service history until the late-20th century.

The 1930s began a new era for the Coast Guard. In 1932, the Service completed work on the modern Coast Guard Academy, located in New London, which produced many of the Service’s future leaders. In 1933, Coast Guard leadership also restructured the Service as part of a Great Depression campaign to streamline government and reduce the federal budget. Developed over two years by Commandant Frederick Billard and Commander Russell Waesche, the new model established an “Area” command structure with an Eastern Area, Western Area, Northern Area and Southern Area. Under the new system, the Area commands assumed control of division operations while districts came under the control of divisions. This tiered system formed the basis for an organizational model still used by the Coast Guard today.

By the late 1930s, the Coast Guard began preparing for another war. In 1936, Commander Waesche was “deep-selected” to serve as commandant and would serve a record-setting nine years as head of the Coast Guard. In the years leading up to World War II, Waesche and his staff prepared for the greatest expansion the Coast Guard would ever face. In 1937, Congress placed responsibility for domestic icebreaking with the Coast Guard, a mission that would expand to international waters during the war. In 1939, war erupted in Europe and the Roosevelt administration moved the civilian-manned U.S. Lighthouse Service from the Commerce Department to the Coast Guard. By adopting the Lighthouse Service, the Coast Guard gained the aids-to-navigation mission. At the same time, it had to absorb hundreds of lighthouses and lightships, a fleet of black-hulled tenders, thousands of buoys and beacons and thousands of personnel to maintain and operate them. Also in 1939, the Coast Guard eliminated the old Revenue Cutter Service division system thereby reducing the Service’s administrative layers to Area commands overseeing districts.

World War II accelerated change within the Coast Guard. In 1941, with war spreading across the globe, the Service was transferred once again from Treasury control to the Navy. In 1942, the civilian-staffed Bureau of Marine Inspection and Navigation moved as a temporary measure from the Commerce Department to the Coast Guard, adding marine safety to the Service’s growing list of missions. During the war, the Service fought once again alongside its fellow military services in the air, at sea, and on land while performing its law enforcement, search and rescue, humanitarian response, port security, aids-to-navigation and marine safety missions. At war’s end, the Coast Guard returned to its place within the Treasury Department after contributing 250,000 men and women to the war effort.

After the war, the Coast Guard experienced significant organizational changes. In 1946, adoption of the Bureau of Marine Inspection and Navigation was made permanent. That year, the Service also changed the 1933 area command system replacing the four Area commands with three—an Eastern Area, Western Area and Pacific Area. And, in 1949, the Coast Guard established “Groups” to oversee smaller units within the districts. Other modifications included district consolidations, and flag officers began to receive district commands instead of the senior captains who assumed them before the war.

The late 20th century saw the Coast Guard undergo more profound alterations. In 1966, the Navy transferred the last of its icebreakers to the Coast Guard making the Service the only federal agency capable of domestic and polar icebreaking. The year 1967 saw Lyndon Johnson’s administration move the Coast Guard from Treasury to the new Department of Transportation. That same year, Congress tasked the Coast Guard with regulating bridges built over navigable waterways and the Service adopted the colorful and easily recognized “Racing Stripe” emblem on its cutters, tenders, aircraft and smallboats. In 1973, the Coast Guard combined the former Western and Pacific areas into one Area, so only an Atlantic Area and a Pacific Area remained with each area covering half the globe and the border running along the Rocky Mountains. By 1987, mergers had diminished the number of Coast Guard districts to ten with the last merger taking place in 1996. That year, the Service combined districts 8 (Gulf Coast) and 2 (Western Rivers) to form a larger District 8.

Congress had tasked the Coast Guard with monitoring and enforcing fisheries laws since the 1800s. However, marine environmental protection and preservation of living marine resources became vital missions of the Coast Guard during the late-20th century. After World War II, numerous high-profile oil spills occurred bringing greater regulation of oil tankers and improved technology for responding to chemical spills. At about the same time, Congress tasked the Service with monitoring unauthorized vessel discharge, enforcing ballast water regulations and ensuring that all commercial vessels met U.S. environmental safety and maintenance standards. Alaska’s Exxon Valdez disaster led to passage of the Oil Protection Act of 1990 (OPA 90). The OPA 90 regulations included mandatory double-hull designs for new tanker construction and a Coast Guard rapid response capability for oil and chemical spills. Enforcement of OPA 90 regulations became one of the largest law enforcement assignments for the Service since Prohibition, and added maritime environmental response to the Coast Guard’s expanding list of maritime missions.

During the same period, two more law enforcement missions emerged in the waters of the Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico. These included alien migration interdiction and counterdrug operations. Within two years of Fidel Castro’s 1959 Cuban Revolution, refugees began to flee his country in large numbers and the Coast Guard initiated frequent migrant interdiction operations. In April 1980, Castro declared the port of Mariel “open” and the Service’s largest migrant interdiction operation began. By the time it ended, over 125,000 refugees had fled Cuba with the loss of only 27 refugee lives. Since the Mariel Boatlift, the Coast Guard has responded to numerous refugee boatlifts from Haiti and Cuba.

In the early 1970s, the demand for illegal drugs rose dramatically in the U.S. The Coast Guard made its first maritime drug seizure in March 1973. During the rest of the decade, the Coast Guard seized over 300 vessels, confiscated over $4 billion in drugs and arrested nearly 2,000 suspects. With the introduction of the Coast Guard’s Helicopter Interdiction Tactical Squadron (HITRON) units on board cutters deployed for counterdrug operations, maritime drug smuggling to the U.S. has been drastically reduced. Today, the Service works closely with other law enforcement agencies, the Department of Defense, and international partners to stop the smuggling of narcotics into the U.S. Counter-narcotic and alien migration operations have made the waters surrounding Florida the busiest region in the Coast Guard’s area of responsibility.

With the September 11th attacks in 2001, the War on Terror set in motion a re-organization of government agencies charged with national security. This process led to the greatest changes seen in the Coast Guard since World War II. Eleven days after 9/11, President George W. Bush set-up the Office of Homeland Security. In December, he signed legislation amending the National Security Act making the Coast Guard’s Office of Intelligence an official member of the U.S. military’s intelligence network and expanding the Service’s role in national defense. In November 2002, Bush signed the Homeland Security Act creating the Department of Homeland Security (DHS). By March 2003, the Coast Guard had left the Department of Transportation becoming the largest and only military agency within DHS. It was a record-setting sixth department swap for the Service. Also in 2003, the Coast Guard commissioned Maritime Intelligence Fusion Centers for each Area command (MIFC-LANT and MIFC-PAC) to provide actionable intelligence to Coast Guard units and commands.

President Bush also signed the Maritime Transportation Security Act (MTSA) to better protect the nation’s ports and waterways from terrorist attacks. The MTSA led indirectly to the International Ship and Port Facility Code and the formation of the Service’s International Port Security Program whose Coast Guard staff members monitor security standards in foreign ports. Under the MTSA, the Service also formed thirteen highly-trained Maritime Safety and Security Teams (MSSTs), supporting the Ports, Waterways, and Coastal Security (PWCS) mission and providing non-compliant vessel boarding capability for Coast Guard missions. In 2004, the Service began forming its own Special Forces unit called the Maritime Security Response Team (MSRT) on the East Coast and, in 2013, began forming a second MSRT on the West Coast. In 2007, the Service also established the Deployable Operations Group (DOG) to oversee its Deployable Specialized Forces (DSF). The DSFs include the Coast Guard’s MSRT, MSSTs, Port Security Units, National Strike Force teams, Regional Dive Locker personnel and Tactical Law Enforcement Teams (TACLETs). Later, the Coast Guard decommissioned the DOG and the Area commands assumed tactical control of the DSFs.

After 9/11, the Coast Guard focused its organization on unity of effort and responsiveness. In early 2002, the Service set-up Joint Harbor Operations Centers in its port commands. In 2003, the Coast Guard adopted the Incident Command System enhancing its ability to work jointly with federal, state and local agencies in major response efforts. Prior to 9/11, field commands had included separate Marine Safety Offices, Vessel Traffic Services and Groups. The Coast Guard combined these activities into a “Sector” structure and, in 2005, began setting-up sector commands throughout its operating area.

Beginning in October 2001, the Coast Guard supported Operation Enduring Freedom with port security, force protection and military outload security. Early 2003 saw the Middle East deployment of Coast Guard cutters and DSFs in Operation Iraqi Freedom. The Coast Guard stood-up new units like the Redeployment Assistance and Inspection Detachment (RAID) to monitor the safety of military cargoes, and Patrol Forces Southwest Asia (PATFORSWA) to support Coast Guard cutters and units in the Arabian Gulf. While RAID was decommissioned in 2015, PATFORSWA continues to support cutters and DSFs in the Middle East.

The Service has responded to major storms since 1900. In that year’s Galveston Hurricane, the worst humanitarian disaster in U.S. history, the Coast Guard’s predecessor services of the Revenue Cutter Service, Lighthouse Service and Lifesaving Service saved hundreds of lives and participated in the city’s post-storm cleanup effort. Over the course of the 20th century, the Service honed its storm response capability as demonstrated in cases like Hurricane Katrina and this year’s record-breaking hurricane season. In 2017, the Coast Guard responded rapidly to hurricanes Harvey, Irma and Maria saving 11,000 lives, providing humanitarian relief to affected areas, correcting more than 1,200 buoys and aids-to-navigation, and assisting in the removal of over 3,600 sunken or damaged vessels. Today, major storm response has become one of the Coast Guard’s most recognized missions.

In 1790, Alexander Hamilton established his fleet of 10 cutters whose sole purpose was law enforcement. These cutters carried a crew of 10 civilian officers and enlisted men or a total of 100 cuttermen. The modern Coast Guard is a military service that employs 238 cutters, 187 aircraft and 1,523 smallboats. To operate and support these assets, the Service has about 36,000 active-duty personnel with 7,300 Reservists and 7,000 civilian employees. The Service also counts 30,000 volunteer Auxiliarists as force multipliers. Today, the Coast Guard is by far the smallest U.S. military service; however, its highly-trained men and women perform the Coast Guard’s 11 statutory missions, many more missions than any other military agency.

Over the past 228 years, the United States Coast Guard has experienced rapid growth in its geographic area of responsibility, mandated missions, and organization through mergers with other maritime services, restructuring, and transfers from one federal department to another. This continuous change has demanded remarkable flexibility and resourcefulness of the Coast Guard. The Service has lived-up to its motto Semper Paratus by adapting and evolving to meet the nation’s ever changing maritime needs and emerging as a global responder, recognized and respected at home and abroad.