Managing the two paths of a nuclear-trained surface warfare officer (SWO[N]) has always been a special challenge, one considered in the February Proceedings Today article “Rethink the Surface Warfare (Nuclear) Option.”1 The author worries that SWO(N)s do not get enough ship driving experience, but such a concern appears to be a more general problem of the times rather than something specific to the SWO(N) community. Instead of highlighting the difficulties of balancing two specialties, it might be better to explore the value a more well-rounded SWO brings to the commanding officer (CO) and crew of a ship, regardless of platform or hull type.

The SWO(N) career path is a mirror image of the conventional path when evaluated through the achievement of milestones.2 Every SWO—nuclear and conventional—spends approximately 5.5 years as a division officer (DIVO), 4 years as a department head (DH), and 15–18 months as an executive officer (XO), usually in sea-going commands.

DIVOs develop shiphandling proficiency, cultivate warfare knowledge and employment, manage an abundance of administrative, maintenance, and operational programs and requirements, and practice the application of authority over small teams. All make their readiness for war a special focus.

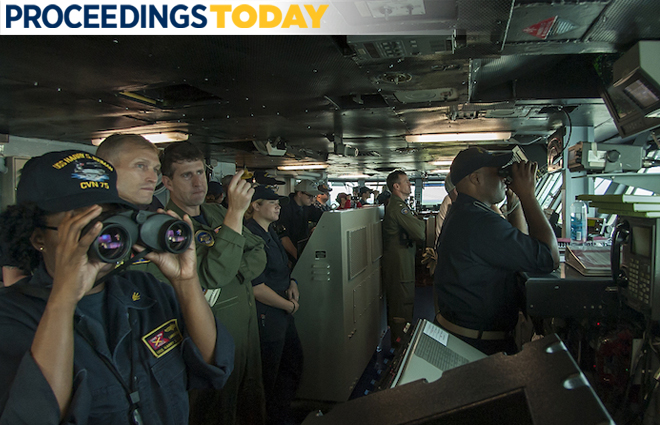

DHs receive baseline and ship-specific tactical and operational training at Surface Warfare Officers School and report to ships ready to build on their DIVO experiences. DHs confer directly with the CO concerning departmental matters, target shiphandling opportunities to improve proficiency and train DIVOs, and work across commands, squadrons, task forces, and fleets to ensure their commands maintain high levels of readiness within the unit, building teams and managing risk in the process.

XOs have the special opportunity to leverage their experience and training to support the CO in the command’s performance of duty, training, maintenance, and good order and discipline.4 This includes major involvement in qualifications, navigation and ship handling. Nuclear SWOs are not handicapped by nuclear requirements but instead improve through the diversity of thought inherent in mastering a technical specialty as well.

In 1982, then-Lieutenant Jim Stavridis considered the issue, when he wrote about using SWOs as aircraft carrier XOs, noting that “the presence . . . of a SWO commander, particularly a successful, post-command tour O-5, would immediately improve the ship's performance in all phases of seamanship and navigation.”3 The nuclear-powered aircraft-carrier (CVN) community today relies on senior SWO(N)s to support the professional development of junior SWOs. Their involvement is crucial to building strong teams necessary to successfully accomplish the mission.

The logic that underlies criticism of the nuclear option applies equally to SWOs’ shore rotations. Though these are considered important to the development of the well-rounded professional officers the Navy needs to fill future leadership billets, these tours likewise require officers to make a change of mindset before they can to go back to being warfighters when they return to sea duty. Submariners value well-rounded officers who know the principles and limitations of the propulsion plants they are operating; SWOs should, too.

SWO(N)s do not choose the nuclear path for the money. There are numerous force-shaping tools to ensure enough ensigns are trained to guarantee ample SWO(N)s are qualified for reactor officer and command that the bonuses need not play a primary role. In Mr. Fogarty’s “Rethink the Surface Warfare (Nuclear) Option” a more accurate analysis of past performance would look at all the manpower/manning, training, and force structure decisions of the last 15 years to understand better the causes that underlie the problems with ship-driving today.5 Most people probably will admit that the division-officer-at-sea approach, commonly referred to as “SWOS-in-a-box,” was not the best idea, but dozens of officers who participated in it have gone on to have successful command-at-sea tours. It is not too much to expect SWO(N) naval officers to serve on conventional and nuclear platforms. The bonus money ensures we retain not only a skillset but also our best and brightest naval officers. SWO(N)s, like all SWOs, are warfighters first and engineers second.

1. Brian Fogarty, “Rethink the Surface (Nuclear) Option,” Proceedings, February 2018, Vol. 144/2/1,380, https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2018-02/rethink-surface-warfare-nuclear-option.

4. CAPT Rick Cheeseman, Director, PERS-41“Surface Warfare Officer Community Brief” 5 January 2018, www.public.navy.mil/bupers-npc/officer/Detailing/surfacewarfare/Documents/SWO%20Community%20Brief%20-%205%20JAN%202018.pdf.

3. LT Jim Stavridis, “Nobody Asked Me, But...A New SWO Billet in the Carrier,” Proceedings, January 1982, Vol. 108/1/947.

4. OPNAVINST 3120.32(series), Standard Organization and Regulations of the U.S. Navy

5. CAPT Kevin Eyer, “What Happened to Our Surface Forces?” Proceedings, January 2018, Vol. 143/1,1379, 24–29.

Lieutenant Commander Walker graduated from Norfolk State University in 2005 and has served on three aircraft carriers, the USS Dwight D. Eisenhower (CVN-69), USS Carl Vinson (CVN-70), and USS Harry S. Truman (CVN-75), as well as the amphibious assault ship USS Bataan (LHD-5) and the guided-missile destroyer USS Carney (DDG-64). He works with the director, expeditionary warfare, as the section head for amphibious warfare shipboard readiness as a requirements manager and resource sponsor.

For more great Proceedings content, click here.