On 10 April 1963, the USS Thresher (SSN-593) sank with all hands during sea trials off the Massachusetts coast. At the time, I was the shipyard watch officer at Portsmouth Naval Shipyard, where the submarine was undergoing maintenance as part of a post-shakedown availability (PSA). I had the honor of knowing many of the crew members.

The Navy introduced the Submarine Safety (SubSafe) Program following the Thresher’s loss, and it has taken many steps to ensure that neither the problems uncovered nor the casualties are forgotten. More important, the procedures instituted in the aftermath continue to be rigidly followed. Nevertheless, as the recent collisions involving the USS Fitzgerald (DDG-62) and the USS John S. McCain (DDG-56) show, safety at sea is an ongoing challenge. Most people working on submarines today were not around when the Thresher was lost, and though SubSafe training includes reference to the Thresher tragedy, we still have much to learn from the details.

In the early 1960s, the Cold War was in an active and dangerous stage. France and the Soviet Union were conducting atmospheric nuclear tests. The Cuban Missile Crisis (October 1962) threatened most U.S. cities with Soviet missiles. As a result, construction of ballistic-missile submarines (SSBNs) became the Navy’s top priority, classified “Brickbat 01.” Portsmouth Naval Shipyard in Kittery, Maine, was building SSBNs and SSNs (nuclear-powered attack submarines). The attack boats competed with the missile boats for the same manpower, materials, and resources, and the missile subs usually won. During the Thresher’s construction, the Abraham Lincoln (SSBN-602) was also being built, and during the Thresher’s PSA, the John Adams (SSBN-620) and the Nathaniel Greene (SSBN-636) were under construction. The Thresher, the newest, most advanced attack submarine in the Navy, was commissioned on 3 August 1961, in spite of all the frustrations associated with being a lower priority.

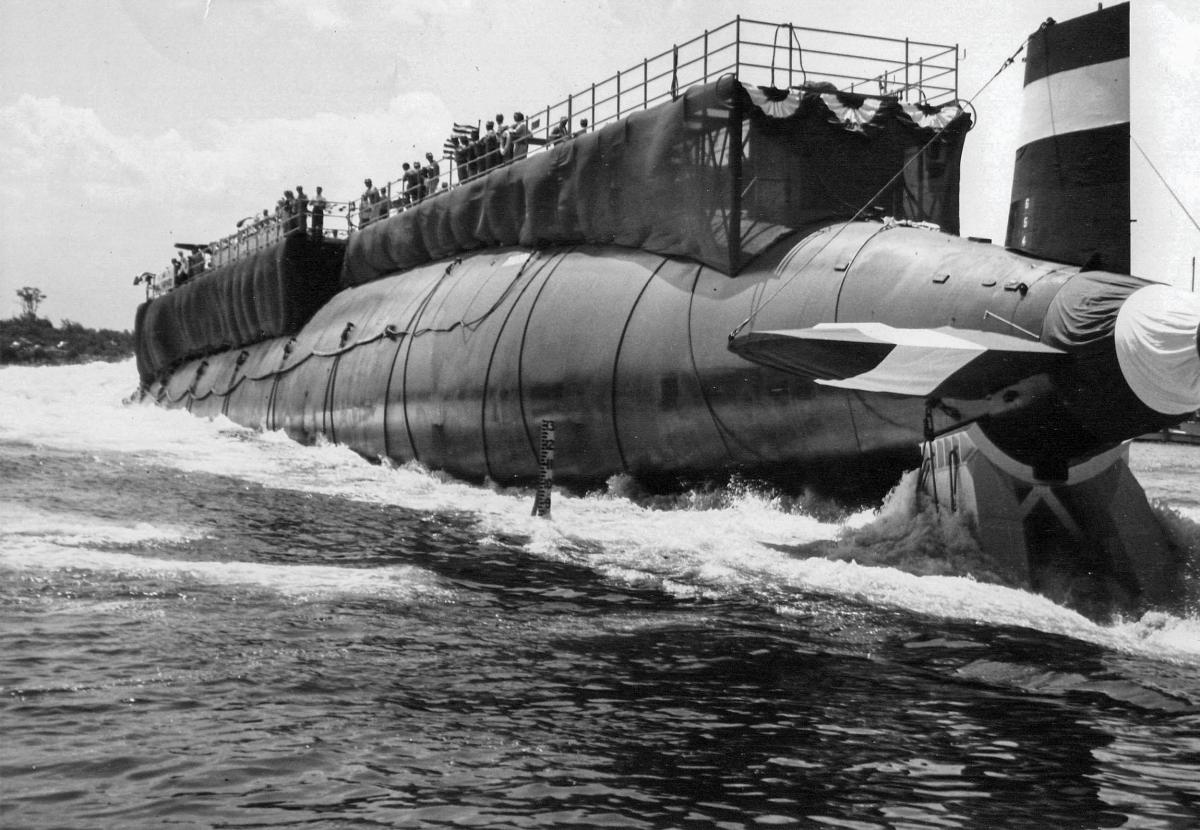

Following delivery, the Thresher exceeded all expectations. During her shakedown, she made it to test depth—the deepest for any sub in the world—more than 40 times. As the first submarine of her class, she was subjected to severe shock tests before returning to Portsmouth Naval Shipyard. The Thresher performed magnificently during these shock trials but was subject to depth restrictions afterward, because the Bureau of Ships advised the shipyard to conduct inspections for any evidence of shock damage. In addition to some alterations, the guidance included inspecting any accessible silver-brazed piping joints.

During the Thresher’s construction, silver-brazed pipe joints were inspected visually and subjected to pressure testing, but no non-destructive test was performed, as ultrasonic testing was in its infancy and not yet in widespread use. Following the shock testing, the Thresher returned to Portsmouth Naval Shipyard for a PSA on 11 July 1962. This availability was scheduled to last six months and consume 35,000 man-days. As workers discovered shock damage and other problems, the PSA was extended to nine months and more than 100,000 man-days.

The Thresher was once again competing with other construction for manpower, talent, and attention during the PSA. Even though the Thresher did not enjoy high priority, commanders were anxious to have her join the fleet. They were ecstatic about the potential this submarine demonstrated during her shakedown period.

As the time approached for the Thresher to go to sea, all the normal frustrations associated with completing a complicated ship were in play. The so-called fast cruise, which permits a submarine to exercise and prove readiness independent of the shipyard, was terminated because of problems with both shipyard and crew. A second fast cruise was successful and the submarine was declared ready for sea.

Senior ships superintendent of the Thresher’s PSA, Lieutenant Bob Biederman, was an experienced submarine officer. He shared with me several times his frustration working this submarine availability. He was concerned that in his opinion the crew needed more time for training—an opinion shared by the Thresher’s court of inquiry.

The Thresher got under way on 9 April 1963. Many people wanted to ride the advanced submarine, creating an overcrowding problem. As a result, some people were told no. One naval officer with a bag packed with personal items was turned away as he approached the brow to board the submarine. Franklin James Palmer, an experienced hydraulic expert, had a bad cold and was instructed to stay ashore. At the very last minute, the doctors approved him to make the trial because of his special expertise.

The plan for this sea trial was to check out the submarine and the crew on day one, then rendezvous with the submarine-rescue ship USS Skylark (ASR-20) on day two to monitor the location while the Thresher conducted a deep dive to test depth. This would be the first time since the shock trials that Thresher dove to test depth.

At approximately 0900 on 10 April 1963, the Thresher advised the Skylark, “Experiencing minor difficulties.” Then at 0918, all communications were lost. Some of the Skylark’s crew reported they heard sounds as if a ship were breaking up. The Thresher, the most advanced submarine of the time and the lead ship of the new class of submarines was lost. The entire handpicked crew and all the guests and talented advisers were gone. The worst possible peacetime Navy disaster had occurred.

The Navy convened a court of inquiry with some of the most experienced naval officers of the time. Their report is comprehensive and after many years has been declassified. One of the key findings was that a silver-brazed piping joint in a seawater system exposed to sea pressure most probably had failed in the engine room. The leak would have damaged an electrical panel, resulting in a reactor “scram”—the reactor shutting down automatically. This action meant the submarine was suddenly left without propulsion or electrical power and was operating on batteries alone.

One of the last communications from the Thresher to the Skylark was “attempting to blow”—that is, to expel seawater from her ballast tanks to ascend—but she experienced difficulty. The court conducted some tests on the Tinosa (SSN-606), a sister submarine under construction at Portsmouth. The Thresher had strainers installed in her blow system to protect delicate valves from debris and dirt. The court theorized that the submarine initiated a blow, which the crew must have stopped as they began to ascend. But when the submarine had to reinstate the blow, the strainers collapsed because of moisture in the blow piping, resulting in no or limited airflow. With no propulsion, and unable to expel water from the ballast tanks, the submarine sank to collapse depth.

When the first messages from the Skylark arrived at Portsmouth, I realized how serious the situation was. Once the Navy recognized the submarine was lost with all hands, the situation became chaotic. None of us was prepared for this. Even now, more than 50 years later, rarely a day passes when I do not think of the tragedy.

I have tried over the years to understand the whys and wherefores of this terrible loss. First, the attack submarine Thresher was built at a time when missile submarines were the top priority. As a result, the Thresher did not always get the best shipwrights or the proper attention from the shipyard. For example, the Bureau of Ships advised the yard to inspect all accessible silver-brazed piping joints in systems exposed to seawater pressure and to remove the strainers in the blow system prior to sea trials. (Silver-brazed joints had a history of problems in earlier submarines that were designed to operate at much shallower depths than the Thresher.) The shipyard discontinued inspecting for shock damage and postponed removing the strainers until after the sea trials.

Another contributing cause may have been the absence of the submarine’s most experienced reactor officer, Lieutenant Raymond McCoole. McCoole’s wife experienced a medical problem and the submarine’s commander told McCoole to stay home and take care of her. His assistant had just completed retraining in reactor operation, where the operating rules to safeguard the reactor are emphasized.

The Thresher had an unusual reactor plant configuration in that the main steam stop-valves were designed to close automatically in the event of a reactor scram. We know for certain the reactor did scram as the submarine was approaching test depth because of sounds recorded by the national sound surveillance system (SOSUS). The loss of reactor function and the closing of steam valves deprived the Thresher of normal electric and propulsion power. As a result, air banks two, three, and four automatically closed, and one bled slowly.

A by-the-book reactor restart could take between seven and ten minutes. Overriding the rules and attempting to open the main steam valves manually also would take time because of their location. It took a special decision to ignore the reactor safety operating rules and open these valves.

When the PSA had grown to more than 100,000 man-days and nine months, the shipyard began to make decisions to get the Thresher finished. The shipyard stopped conducting inspections for shock damage, stopped inspecting silver-brazed piping joints, and postponed other items, such as removal of the strainers in the blow system. Although the Thresher was not the highest priority for the shipyard or even perhaps the Navy, the operating forces really wanted this submarine. As a result, Portsmouth Navy Shipyard wanted to finish the Thresher and get on with the other submarines under construction. No one appears to have considered that sending a submarine to sea trials and test depth for the first time following shock trials might put her survival in jeopardy.

Looking back at this truly sad state of affairs, it is clear the Thresher’s crew needed more time to train, and the shipyard should not have stopped inspecting. The technology to inspect silver-brazed joints using ultrasonic testing was available, albeit it its infancy. Such testing might have revealed some of the critical joints that were not safe. Configuring the main steam stop-valves to fail closed during a reactor scram was later proven by actual tests to be unnecessary. In fact, the Thresher’s reactor plant could have sustained dragging steam from a scrammed reactor for more than 20 minutes without any damage to the plant. In retrospect, we—those in charge at the time—sent this submarine to sea too soon. More time may have better prepared her.

What if the Thresher had survived the casualties and returned to the shipyard? All or at least many of the deficiencies might not have been corrected. We probably would have continued building submarines with silver-brazed joints and the reactor plant configuration would not have been changed. The SubSafe program would not have been established, and the Submarine Safety Center might never have been created. The complete review of submarine design would have waited for a future tragedy.

As a result of this loss, submarines today are much improved and safer. The 129 men on the Thresher did not die in vain. We must keep this story and history alive.