Faced with massive growth in “short of military conflict” maritime challenges, 21st-century U.S. sea power is deficient. This deficit could be significantly remedied at home and abroad by substantially increasing the capacity of the Coast Guard. Building a sizable 21st-century Great White Fleet of cutters would provide more than just a military instrument for combatant commanders and national leadership; it could offer a set of agile military, diplomatic, intelligence, and law enforcement options ideally suited to counter complex threats that currently go largely uncontested across the maritime domain.

The 21st-century maritime operational environment is infected by a rise in violent extremism, gang violence, and foreign fighter migration; the convergence of transnational networks; hard to attribute state and non-state proxy threats; failed and failing states; food insecurity and immigration; weapons of mass destruction (WMD) proliferation; an increase in natural disasters; and vulnerabilities inherent in a flourishing globalized economy. These threats feed an insatiable multitrillion-dollar black market economy while challenging the rule of law and regional stability. Non-state threats—many of them maritime challenges—cannot be effectively defeated over the horizon or with boots-on-the-ground in theater. They must be met where they are most vulnerable and international law permits—in the maritime domain with “boots-over-the-gunwale.” Instead of talking about a 355-ship Navy, the nation should be talking about a 400-ship U.S. National Fleet that more fully leverages the Coast Guard to act as a unique instrument in international security and diplomacy through enhanced partnerships worldwide.

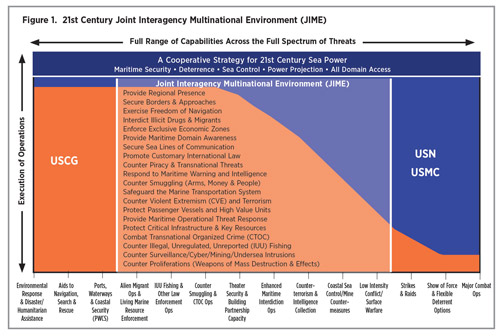

Maritime threats, challenges, and demands across the Joint Interagency Multinational Environment (JIME) continue to proliferate (see Figure 1 below). In general, the left side of the spectrum is oriented to the homeland and the right side is oriented abroad. At home, the significance of maritime security has been rooted in our nation’s history since 1790, when Alexander Hamilton had the vision: “A few armed vessels, judiciously stationed at the entrances of our ports, might at small expense be made useful sentinels of the laws.” However, the gap in rule of law abroad remains a significant delta allowing transnational and transregional bad actors to operate with impunity.

Today, the U.S. marine transportation system facilitates nearly $9 billion in daily maritime trade. Concurrently, maritime governance—to conserve and protect critical resources—over an expansive U.S. exclusive economic zone (EEZ) continues to grow in importance. In the 18th century, Hamilton’s “sentinels” buoyed a nation raising revenue to overcome British imperialism. Today, the Coast Guard safeguards sea lanes and exerts U.S. sovereignty within the U.S. EEZ as far west as Guam and east to Puerto Rico, and as far south as American Samoa and north to the Arctic Ocean, preserving the lifeblood of our $4.5 trillion maritime economy, enabling U.S. power projection, and promoting an international rules-based order across the global commons.

Likewise, the major combat power projected at the right end of the spectrum ensures that a U.S. naval presence remains on station to detect, deter, and defeat nation-state aggression from China, Russia, Iran, and North Korea. In addition, this forward presence enables timely kinetic action against transnational terrorist groups such as al Qaeda and ISIL, denying them safe haven and keeping adversaries in a perpetual mode of self-preservation. Investment at the right end of the spectrum in next-generation cruisers and destroyers, aircraft, submarines, and the cyber domain remains critical to fight and win.

While capability investments at each end of the spectrum remain essential, insufficient resourcing of salient sea power within the JIME is of mounting strategic concern. The horizontal axis in Figure 1 outlines, from left to right, the variety of U.S. National Fleet missions, from lower to higher intensity operations; the vertical axis represents the general execution of duties, with the blue (U.S. Navy/U.S. Marine Corps) and orange (U.S. Coast Guard) waves depicting the fluid intersection of responsibilities between the services. The confluence of operations occurs within the JIME, which outlines a multitude of broad and diverse military missions and constabulary challenges critical to protecting the homeland.

Build Partnerships

Smart resourcing is essential to meeting 21st century maritime threats. Nearly a decade ago, while appearing before the Senate Appropriations Committee, Admiral Mike Mullen, then-Chief of Naval Operations, testified, “I believe an international thousand-ship navy offers a real opportunity to increase partner nation capabilities while reducing transnational crime, WMD proliferation, terrorism, and human trafficking.” Today, building partnership capacity remains central to effectively operating across this shared mission space to counter transnational organized crime (CTOC), terrorism (CT), proxies, and nation-state aggression and provocations short of armed conflict. The key to unlocking lasting international partnerships to combat these growing lower-end threats rests in relationships built upon trust and respect that are mutually beneficial and not perceived as overbearing by partner nations.

The Coast Guard brings unique partner-building capabilities to the fight. An active littoral constabulary presence in partnership with cooperative nations can limit the freedom of movement enjoyed by transnational and transregional threat networks. Conventional wisdom is, “Give a man a fish; feed him for a day. Teach a man to fish; feed him for a lifetime.” Despite significant outflows of U.S. maritime security initiative monies, the regional effects achieved are often fleeting, misunderstood, or lack proper control and staying power. Forging lasting international maritime partnerships can achieve real maritime law enforcement gains by teaching countries how to strengthen the rule of law. Given greater capacity, the U.S. Coast Guard is best suited for this task.

The Coast Guard, for instance, has continued to optimize authorities and capabilities within the Western Hemisphere through more than 45 bilateral counterdrug agreements tailored to each country’s desires. These efforts have remained in force, denying drug smugglers safe havens within territorial seas. Similarly, shiprider agreements—such as those with Oceania and Indonesia—allow for an enforcement official from the host country to embark a U.S. Coast Guard cutter for the purpose of patrolling within its EEZ and/or territorial seas. During such operations in Pacific island EEZs and territorial seas, the U.S. cutters come under the authority of the embarked country’s officials to enforce their laws, help protect marine resources, enhance maritime domain awareness, increase law enforcement presence, and expand the host country’s at-sea law enforcement capabilities.

While these partnerships remain strong, the effectiveness of these agreements in CTOC and safeguarding EEZs is hampered by huge capacity challenges within the Coast Guard that limit its presence and engagement. A 21st century Great White Fleet could renew and bolster the U.S. National Fleet concept by offering a unique instrument of international security and diplomacy, extending an olive branch to willing and committed nations that desire to better safeguard their approaches and EEZs. The 21st-century Great White Fleet could provide the United States more affordable and mutually beneficial regional access that would be scalable, more mission relevant, relatable, and less threatening to partner nations than a larger, gray-hulled fleet.

Promoting international security abroad in this way would lighten the national security load in our approaches and make securing our maritime borders more achievable. Threats would be interdicted and dismantled as far from U.S. shores as possible. As our air and land borders continue to be fortified, our maritime border must not be neglected, because threats will flow across the path of least resistance. For all these reasons, the Coast Guard’s increasing value and importance needs to be recognized and resourced.

Operate Across the Full Spectrum

The need for a larger Coast Guard is driven not just by the rise of non-state actors, but also by state actors that operate below the threshold of what would yield a traditional military response. The Coast Guard could provide capable, less-provocative platforms to deal with situations such as China’s land reclamation and aggressive actions in the South China Sea. The less-threatening nature of the Coast Guard would allow it to pursue credible littoral partnerships, provide a wider range of military access, and garner increased maritime domain awareness and intelligence. It would enable the United States to carry out a wide range of CTOC and CT missions, contest excessive maritime claims, and promote customary international law. At the same time, it would enable other constabulary and diplomatic options conducted in concert with partner nations to combat a wider range of bad and belligerent actors.

The Gulf of Guinea, Mediterranean, Caribbean, Southwest Asia, and Eastern Pacific waters offer additional areas to promote cooperative international security. Many nations are seeking assistance as transnational crime syndicates flourish, foreign fighters flow into regions, and violent extremism spreads.1 The current challenges across the East and South China seas also offer an opportunity to test a more diplomatic maritime approach that capitalizes on existing U.S. Coast Guard relationships with China’s Coast Guard and other partner nations in the region.

U.S. Coast Guard efforts within the Western Hemisphere reinforce the potential operational return on investment that could be achieved by increasing the capacity of the smallest U.S. armed force. In 2016, four additional cutters were surged to the Western Hemisphere transit zone to combat brazen traffickers of illicit arms, people, and drugs. These criminal ventures now often exceed $100 million per trip and exploit largely ungoverned maritime pathways to move illicit cargos between safe havens. Despite the premature loss of U.S. Navy frigates to sequestration, the Coast Guard double downed on its Western Hemisphere Strategy which enabled the interdiction of 443,794 pounds of cocaine estimated at more than $5.9 billion.

Working in cooperation with U.S. Southern Command’s Joint Interagency Task Force South, the service achieved record-breaking results from this focused surge between FY2015 and FY2016. The amount of cocaine removed was up 40 percent (201 metric tons from 144 metric tons); detainees up 16 percent (585 from 503); vessels seized up 18 percent (172 from 146); and cases referred for U.S. prosecution up 16 percent (156 from 134). The 201 metric tons of cocaine removed in FY2016 shattered the previous record of nearly 167 metric tons removed in FY2008.1

Despite the Coast Guard’s success in FY2016, the reality is still that less than 20 percent of known cocaine being transported over maritime routes was acted on and pursued. U.S. Southern Command Commander, Admiral Kurt Tidd, reiterated his predecessor General John Kelly’s assessment, testifying, “I do not have the ships . . . to execute the detection-monitoring mission . . . we tend to have between five and six surface ships, those are largely Coast Guard cutters . . . in order to interdict at the established target level . . . up to 21 surface platforms (are needed).”2 Disrupting these pathways and dismantling these illicit networks remain the most direct and productive approaches to combating transregional threats converging at our borders. Concentrating resourcing efforts on interdictions at sea, where bulk illicit shipments are most vulnerable, provides the best return on investment in not only quantities seized, but also future actionable intelligence gained. Forward-deploying the Great White Fleet concept across this and other combatant commands could net similar gains in CTOC and CT sea lanes internationally and attack these growing threats and pathways at each end by building more productive partnerships and focusing on mutual success.

Build a New Great White Fleet

Enhancing regional security in partnership with willing nations requires a 21st-century Great White Fleet of forward deployable (or stationed) national security cutters (NSCs), offshore patrol cutters (OPCs), and fast response cutters (FRC). The mix of platforms and duration of presence would be tailored to the distinct geographies and vary based on the receptiveness of the host nation(s), problem sets to be addressed, and mutual goals of the combatant commands and partner nations. Building on a proven bilateral approach for counterdrug operations and EEZ enforcement, the Great White Fleet would leverage existing agreements—based on the extent to which partner governments are willing—to strengthen CTOC and CT across the JIME.

From an acquisition perspective, doubling the size of both the OPC (from 25 to 50) and FRC (from approximately 50 to 100) programs equates to the projected cost of one Gerald R. Ford (CVN-78)-class aircraft carrier (approximately $13 billion). Furthermore, procuring an additional seven NSCs over the nine planned would cost the equivalent of one Zumwalt (DDG-1000)-class guided-missile destroyer (approximately $4.2 billion). The NSC and OPC both offer more than three times the on-station time between provisioning than is afforded by a littoral combat ship (LCS).

Building more OPCs also could rapidly grow the National Fleet by leveraging commercial shipyards outside the mainstream industrial complex. These shipyards may be able to provide better value to the government during an economic downturn in the oil and offshore supply industry. Further leveraging this acquisition would continue to drive down the cost of the OPCs and provide an additional industrial base to build a 400-ship National Fleet of ships with far lower operating and maintenance costs than the LCS.

Redirecting proposed future LCS/frigate dollars (approximately $14 billion) to a Great White Fleet to modernize the U.S. National Fleet mix would provide a greater return on investment and more staying power abroad. For instance, building international security cutters—NSCs with Navy-typed/Navy-owned enhancements such as the SeaRAM antiship cruise missile—could offer combatant commanders a truly useful “frigate,” leveraging mature production lines that now operate at only 70 percent capacity. These estimates are for relative comparison and do not include the associated aviation, infrastructure, basing support agreements, and personnel plus-ups that are needed to provide a more credible and persistent presence across the JIME. But investing in a larger Coast Guard and the supporting infrastructure would return high dividends.

Attune the National Fleet

The rapid expansions of coast guards by South China Sea nations highlight their new-found utility to exert and protect sovereignty claims. Proposed cuts to the already austere U.S. Coast Guard budget demonstrate that an appreciation for the extraordinary utility and relevance of our Coast Guard is lagging. Given the daunting maritime challenges ahead, growing the capacity of the Coast Guard through significant capital investment seems a reasonable, effective, and sensible option. Investing in a larger Coast Guard would demonstrate the United States’ international commitment to the rule of law and human rights through a more cooperative and less provocative approach to national and international security. It also would demonstrate the ability of the U.S. government to overcome bureaucratic stovepipes and lobbies and invest in a more agile, adaptive, accountable, and affordable future joint force—a force better equipped to contribute to a more peaceful and stable world through well-crafted operational approaches.

Today the Coast Guard is simply too small to call on to meet the complex maritime threats across the JIME, much less support the wider joint force across the globe. Recognizing the utility of a 21st-century Great White Fleet could be to the new administration what the 20th-century Great White Fleet was to President Theodore Roosevelt—an opportunity to reinstill national pride and prestige while improving U.S. national security. It is time to build a U.S. National Fleet for the ages, attuned not only to the evolving character of conflict, but also to rule of law and our international partners’ needs.

1. USCG Office of Law Enforcement Statistics.

2. Cheryl Pellerin, “Tidd: Global Terrorist, Criminal Networks SouthCom’s Biggest Threat,” Department of Defense, www.defense.gov/News/Article/Article/691833/tidd-global-terrorist-criminal-networks-southcoms-biggest-threat.

Captain Ramassini is a U.S. Coast Guard cutterman and recently served as the U.S. Coast Guard’s liaison within the Office of the Secretary of Defense for Policy. He has been selected as the plankowner commanding officer of Kimball (WMSL-756) scheduled to be delivered in 2018.