Several times each year, a commanding officer (CO) is relieved because of a “loss of confidence” in his or her ability to command. Too frequently, that announcement is followed by conversations like this:

“Did you hear that (blank) was fired from Command?”

“Yeah, saw that coming back when I was (insert position). I figured that at some point that behavior would catch up with that officer!

“So why didn’t you speak up?”

Command is a gift, not to be taken lightly, and to have one of an ever-decreasing pool of these cherished positions wasted on someone who was known by peers to be destined to fail is a shame. By the same token, some who have failed and been fired may have convinced themselves that the risks they were taking or the behaviors they were participating in were reasonable—when history has shown they were not.

Perhaps one factor in this equation is the secrecy that surrounds most firings, which can hide or bury lessons that could be teaching points and help prevent a repeat of history. These lessons are more than “keep your zipper up and don’t scrape paint.” Two of the minimum standards of leadership at sea are the ability to drive ships without hitting other ships or the bottom and the ability to recognize that, as a former mentor of mine put it, “that command star does not make you any better looking.” But there are often trend lines and areas where a compilation of past events—with some context and explanation—could serve a purpose.

Truth in Advertising

I had a few close calls along the way. The destroyer I was commanding once traded paint with a navigational buoy and once with another ship (although, in that case, I was moored at the pier). The cruiser I commanded had a close call with another ship and lost a towed array to Davy Jones when driving too fast in water that was too shallow. In each case, I was saved by a combination of mitigating circumstances, a leader who was supportive and forgiving of mistakes, and a bit of luck that the damage was not worse than it could have been.

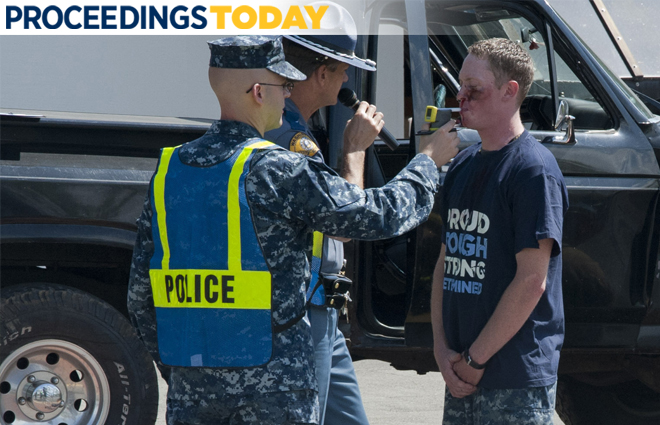

Given second chances, I truly worked hard to learn from my mistakes. As a young division officer, after drinking too much on a Sunday afternoon at a beachside bar in San Diego and sleeping it off in my car, I made the poor decision to drive back to the base the next morning. When I rolled the window down, the young gate guard held his nose and advised me to turn around and park outside the gate and walk to work, otherwise he would have to make me submit to a breathalize test. His benevolence saved my career. My behavior changed that day, and I have kept drinking and driving separate ever since—others have not been so lucky.

What To Do?

It all starts with ensuring the Navy culture is one that is supportive and more forgiving of mistakes. Sharing lessons learned of those close calls (whether at sea or related to personal conduct) is difficult and must be more widely encouraged across the fleet. When CO firings—and possibly the removal of executive officers (XOs) and command master chiefs—do occur, the Navy should find a way to formally capture the circumstances and categorize them in a standard format. Without naming names or places, a generic version of the story should be created, and a summary of the event—redacted and approved by a judge advocate (JAG)—could be useful to the fleet.

In my experience as a chief of staff of Surface Forces Atlantic, rarely was firing for personal conduct or leadership the result of a stand-alone event. There often was a series of lapses, frequently with counseling involved, that preceded the decision to end a career. In every case, there was a story with teaching points that a learning organization could use to improve behavior to avoid similar incidents. Certainly this would be better than relying on unnamed sources in the Navy Times.

The Elephant in the Room

But what about the “I saw that coming” comment? That is a tough one. Department heads and executive officers display almost unwavering loyalty to their commanding officers, and the community can be unforgiving of individuals who reach out to higher leadership when the CO is out of bounds. This is especially aggravated in XO/CO fleet up situations where the default response may be accusations of disloyalty or aspirations to accelerate the turnover.

The 360-degree surveys are a step in the right direction, but a more direct approach is necessary. At every wedding I have attended, the minister has asked the congregation, “If anyone knows of a reason why this matrimony should not take place, speak now or forever hold your peace.” Perhaps after each command selection board, a survey of the prospective commanding officer’s peers or former subordinates could be conducted asking a similar question. A negative endorsement need not derail a career, but perhaps it would lead to an interview and a shot across the bow or a confidential mentoring session by a trusted leader. Brutal? Yes. More brutal that an emergent change of command to a ship and crew? Probably not. Worth the risk of an embarrassing discussion? According to the younger version of myself after that conversation with the gate guard—absolutely.

Captain Cordle retired in 2013 after 30 years of service. He commanded the USS Oscar Austin (DDG-79) and USS San Jacinto (CG-56). He is the 2010 recipient of the U.S. Navy League’s Captain John Paul Jones Award for Inspirational Leadership.

EDITOR’S’ NOTE: This article was submitted well-prior to the USS Fitzgerald (DDG-62) incident.

Read more on this subject from Captain Cordle at the USNI BLOG:

Collision Investigations: What I learned ... Captain John Cordle, U.S. Navy Retired

More from Proceedings Today and Proceedings :