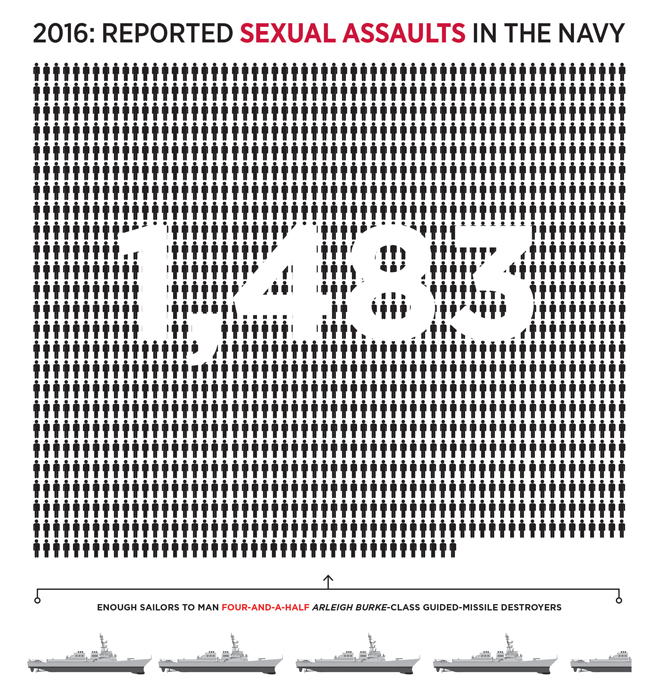

Last year, 1,483 Navy personnel reported being sexually assaulted. That is enough sailors to man four-and-a-half Arleigh Burke-class guided-missile destroyers. Along with those 1,483 sexual assault victims, there were 1,483 alleged perpetrators. Of the people accused, 75—barely more than 5 percent—were found guilty at trial. Of the 95 percent who were not convicted, whether you believe them to be guilty or innocent, many still are serving in the fleet. The Department of the Navy says “it is deeply committed to achieving a culture of gender respect—where sexual assault is never tolerated, and ultimately eliminated.” If this is the Navy’s goal, why don’t the statistics support it? Sexual assault and harassment are serious problems in the U.S. Navy and need to be further examined, talked about, and addressed.

The sexual assault problem in the Navy begins with the culture. For many years, military service was considered a man’s profession, one women were too weak to undertake, one in which women did not belong. Many men still agree with former Senator James Webb, who wrote in a 1979 Washingtonian article that women “can’t fight.” Modern-day combat and warfare are no longer comprised primarily of hand-to-hand combat. With the constant advancement of vessels and weaponry, traits beyond brute strength and killer instinct are necessary in our nation’s warriors. With all due respect to Mr. Webb, the most powerful weapons we as humans possess are our brains.

The recent “Marines United” scandal put sexual assault and harassment in the Marine Corps in the public eye, but the Navy is not immune to this type of behavior. Requests for nude photos have been made to female sailors on board the USS Dwight D. Eisenhower (CVN-69), Harry S. Truman (CVN-75), Theodore Roosevelt (CVN-71), and Ronald Reagan (CVN-76), and at naval bases in San Diego and Norfolk. Sailors seem to have gotten the impression that this behavior is acceptable, or that they can get away with it. With only a 5 percent chance of being found guilty, this impression is not unfounded.

Sharon L. Graham examined why female surface warfare officers (SWOs) generally choose to leave the community much sooner than their male counterparts and found that one of the three main factors was the “perception of discrimination, sexual harassment, and lack of respect for women.” Of the 49 people who participated in the study, every one—both male and female—said they had witnessed discrimination against women in the workplace, though not all of them had been personally victimized. One active-duty female SWO explained, regarding sexual harassment and assault, that when “you try to report it and get support, it kind of gets swept under the carpet, so, you know, I don’t want to be involved with that.” Many women in the study said they did not want to be a part of a community that allowed this behavior, and the fact that upper-level leadership allowed it made them want to leave either the SWO community or the Navy altogether.1

The Navy can address the prevalence of sexual assault in the fleet with interactive training that raises awareness. At the naval base in Yokosuka, Japan, PowerPoint presentations on sexual assault were traded for actors role-playing real-life scenarios. Many sailors agreed it brought more emotion to the issues and made them seem more real. One sailor even stated, “You hear about these situations but when you see it physically, it bothers you more.” This type of training should be widely implemented across the Navy. The Navy also could bring in service members who are survivors of sexual assault or harassment and are comfortable speaking about their experiences to share their stories. When people can connect a story to a face, it makes it more personal, and is more likely to affect them. As a result, such experiences can help motivate some individuals to make positive changes in their actions.

Sexual harassment and assault in the military should not be taken lightly. They present a serious problem that has been plaguing the Navy for decades. The culture in the Navy needs a drastic transformation. People must stop blaming the victim, sweeping things under the rug, and making excuses. Victims need to feel comfortable reporting and be confident that their assailants will receive the punishment they deserve. This shift in culture by holding people accountable begins with Navy officers and senior leadership. Every sailor must feel honor bound to prevent sexual assault and help those who have been victims.

1. Sharon L. Graham, “An exploratory study of female surface warfare officers’ decisions to leave their community,” unpublished master’s thesis (March 2009), http://calhoun.nps.edu/handle/10945/2901.

Ensign Kennedy graduated with distinction as a member of the U.S. Naval Academy Class of 2017. She received the Captain Charles C. Hendrix Award as the top graduate in the Oceanography Department. She is a native of Grand Island, New York, and is training to be a surface warfare officer.