As the new commanding officer of U.S. Coast Guard Cutter Morgenthau (WHEC-722), I knew endeavoring to understand the needs and gain the perspectives of the Morgenthau’s officers and crew would be paramount to commanding effectively. As I met with these 180 or so wonderful men and women, I quickly realized that my chief corpsman, Chief Petty Officer Cecil “Doc” Henson, was the key to my insight into the morale and well-being of our command. Doc Henson, as he was affectionately called, placed service above self and nurtured extraordinary working and personal relationships with all members—from myself through the most junior Coast Guardsman.

Cecil always had the pulse of the crew. His sickbay was open to all, anytime, to drop in and chat. He often sought me out to inform me of how my decisions—especially those that were not very good—were affecting the crew. I quickly learned that a stop by sickbay was crucial to finding out what actually was happening on the deckplates. With Doc Henson as my confidant, I had insights into how the Chief’s Mess—the heartbeat of all Coast Guard cutters—and the crew were reacting. When the mantle of command seemed to be a bit too heavy, Doc was always there to “administer” some wise counsel. A great deal of the success our team enjoyed when I served as their commanding officer was attributable to “my Chief.”

Perhaps Cecil’s greatest strength was that he honed his skills and used them to help people accomplish the mission. Prior to joining the Morgenthau, he had served as the independent duty corpsman for Group Cape Hatteras in North Carolina, where there was no practicing doctor for the entire island chain. He alone was the complete medical corps.

Cecil and his family were there only a few days when late one night, his phone rang. The caller had three young daughters and one had a fever. Cecil basically dispensed the “take two aspirin and I’ll see you in the morning” medical advice. He then returned to bed. His wife asked Cecil what the call was about. When he told her, she asked, “What if this was one of our young boys?” Cecil promptly called the father back and had him bring all three girls over to the clinic immediately. From that point forward Cecil made a vow not to turn anyone away ever again.

His time on the Banks was filled helping Coast Guard personnel and civilian residents of the area. Cecil recalled the Coast Guard command getting a nice letter from one of the many whom he assisted and subsequently was presented an award. In Cecil’s words, however, his “biggest reward was just being lucky enough to have had the chance to use my skills to help people.”

Cecil continued to help and lead people everywhere he served. After selection to chief petty officer—joining a very special cadre of senior enlisted leaders—he was assigned as an independent duty corpsman on a “big white ship.” The Morgenthau and I were blessed to have his enthusiastic leadership.

Cecil was especially in his element during the Morgenthau’s refresher training in San Diego. Refresher training is where we were tested and graded on every shipboard evolution by Navy inspectors, affectionately referred to as shipriders. During a man overboard response and recovery drill, one shiprider was hurrying up a ladder to evaluate our performance and struck his head on a metal casing. He immediately was taken to sickbay for Doc to suture him up. He came to at about the fourth stitch and asked Doc, “What is going on?” Doc told him he had been injured judging the man overboard drill. Cecil asked, “Do you want these last two stitches in?” The shiprider said, “Yes,” so Chief Henson asked him if we performed the drill properly. He said, “Of course, you did it perfectly.”

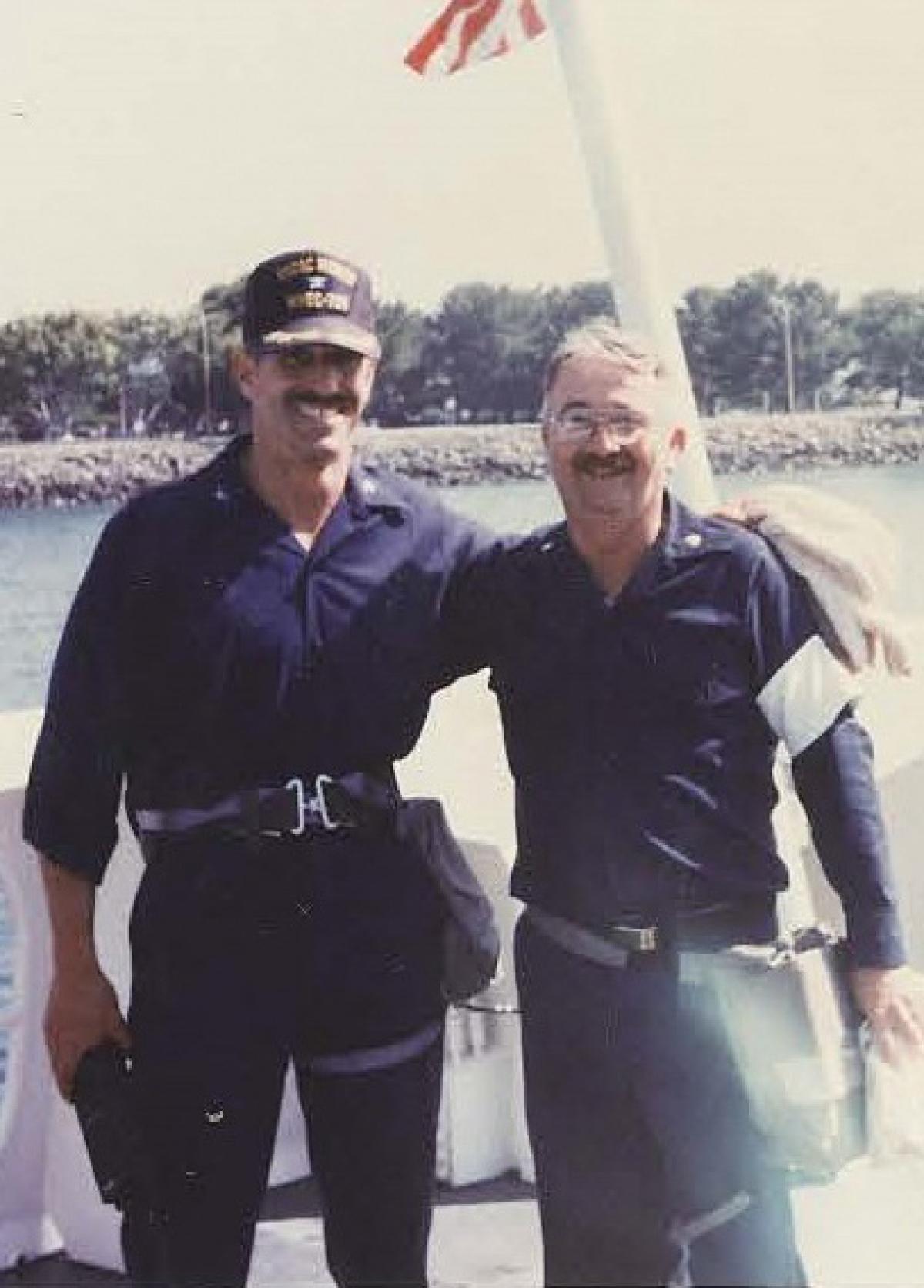

Cecil knew how to build a unique rapport with the Navy shipriders—most being fellow chief petty officers—which included keeping them well fed. He gave our ship a distinct advantage. So much so that on the day of the final exam, the senior shiprider gave our Doc a few “helpful hints.” At the completion of that most arduous day and our “clean sweep” of all training awards, Cecil and I were standing on the ship’s fantail—dressed out in our battle gear—recounting the activities. Cecil asked if he could take my picture. I said only if he was in it too. That is the iconic picture of the two of us that both Cecil and I have cherished all these years. I learned later that he kept that picture in his wallet throughout the remainder of his life.

There is more to the ship story. Military service is a family affair. The Morgenthau also was privileged to have Doc’s wife, Sam, as our volunteer ombudsman—the communication conduit between the command and our families. This is an important role, but normally is “routine” in preparing families for deployment, “passing the word,” and arranging a hearty welcoming on the pier upon return from sea. Sam certainly did not know what she was getting into when she signed up with us.

We experienced two major events that challenged her to help our families get through some extremely difficult times. The first was the March 1989 grounding of the Exxon Valdez tanker and the massive oil spill. Our three-month Alaskan fisheries patrol stretched to four and one-half months with command-and-control responsibilities for the oil containment and cleanup efforts. No one knew when we would be released to return home.

Later that year, many families came into Alameda to see the ship off. Just three hours after we departed, the Loma Prieta earthquake struck San Francisco, collapsing the Cypress Viaduct through which many families had traveled. In both instances, Sam managed the situations as they were evolving in real time, counseled distraught families, and enabled us to carry out our missions successfully. At the same time, the other half of the team, Cecil, cared for our crew members while we were deployed. For Sam’s and Cecil’s superb support throughout these ordeals, every member of our crew and their families and I will be forever grateful.

I must confess that I made a serious mistake at my change of command. Invariably, if you try to recognize everyone who contributed to the success of your unit, you are bound to leave someone out. To this day, I do not understand how I overlooked calling out my Chief, for all he had done—for always being there for the crew and me. Cecil never mentioned it, but others came up and rightfully pointed out my grievous error. As things turned out, however, I was later given opportunities to make this right. Cecil subsequently was assigned as clinic supervisor in Kodiak, Alaska. When officiating a change of command at Base Kodiak, I publically apologized and praised his unique character and unselfish service.

For the remainder of my active-duty career and thereafter, Cecil and I remained great friends. I could continue to call on him anytime for good counsel. In fact, he routinely would call me, and no matter how difficult a situation I might be in, a few old sea stories of our times together would make all the difference to me.

Of many remarkable things about Cecil, he was a friend and mentor to all who worked for him. A clinic supervisor multiple times, he helped many hospital corpsmen (now health services technicians) progress to chief petty officer or above. He gave them the opportunity to accomplish their goals and made sure nothing stood in their way. As Cecil recounted at his retirement, at which I had the very special honor of speaking, “They all turned out well, and others wanted them to work for them because of what they had accomplished.”

Subsequently they would come by to see Cecil and thank him for letting them have the chance to do better. Some who made senior chief refused to advance any further. They wanted to have that “one star” that made them just like him, a senior chief in the Coast Guard.

As Cecil said, “All they wanted was a chance to do well—and they did it.”

They did it because this extraordinary man profoundly touched the lives of many of us ordinary people. He set an example for all to emulate. I learned from Cecil that the secret to success of any chief is to hone your skills to help people accomplish their mission, have your ear to the deckplates, invest in others’ success, and know how to advocate for the crew to their captain, and for the command to the crew.

Senior Chief Petty Officer Cecil “Doc” Henson, U.S. Coast Guard (Retired), crossed the bar on 16 April 2016. He will be forever missed.