Among the dozens of law enforcement ships patrolling China’s maritime periphery, some have shown a special knack for feuding with foreign mariners—none more so than the fisheries cutter Yu Zheng-310, or YZ-310. In the five years since her commissioning, she has navigated Chinese-claimed waters from the Senkaku Islands to the James Shoal, the mythical “southernmost extent of Chinese territory.” She has jockeyed with Japanese patrol ships, browbeaten the Indonesian coast guard, menaced Philippine fishermen, and called the bluffs of the Vietnamese Navy.

YZ-310 is not a typical vessel. Few Chinese ships can claim her many attainments in the “war without gunsmoke” taking place in the Western Pacific.1 However, none of her operations is unique; none is without precedent. Examining her past, then, sheds light on the roles and missions of Chinese maritime law enforcement (MLE) writ large. Doing so also offers a richer, more variegated understanding of the men and women guarding China’s blue-water frontier, whose actions could easily precipitate a regional war.

First (and Only) in Her Class

YZ-310 was the brainchild of Wu Zhuang, the ambitious “tough guy” (yinghan) of China Fisheries Law Enforcement (FLE). Wu was commander of the service’s 1994 mission to occupy Mischief Reef, champion of harsh policies to expel Vietnamese fishermen from the Paracels, and author of the March 2009 assault on the USNS Impeccable (T-AGOS-23). In the 1990s, Wu began lobbying the Ministry of Agriculture for funds to procure large-displacement cutters. But in the contest for funding, FLE lost out to China Marine Surveillance (CMS), a rival agency. Whereas CMS was authorized to build more than a dozen new large cutters, FLE had to remain content with just a handful of oceangoing ships, many quite old.2

Thus, when FLE did receive approval in 2001 to procure one new large-displacement cutter, it was a big deal. The ship, which would ultimately be named YZ-310, was designed by the 701 Research Institute of the China Shipbuilding Industry Corporation and built by Guangdong Zhanjiang Haibin Shipbuilding Company. The process from approval to commissioning took nearly ten years. For unknown reasons, construction did not begin until 28 February 2008. YZ-310 finally was delivered to her eager owners, the South China Sea Branch of FLE, in September 2010—the first and only ship in her class.3

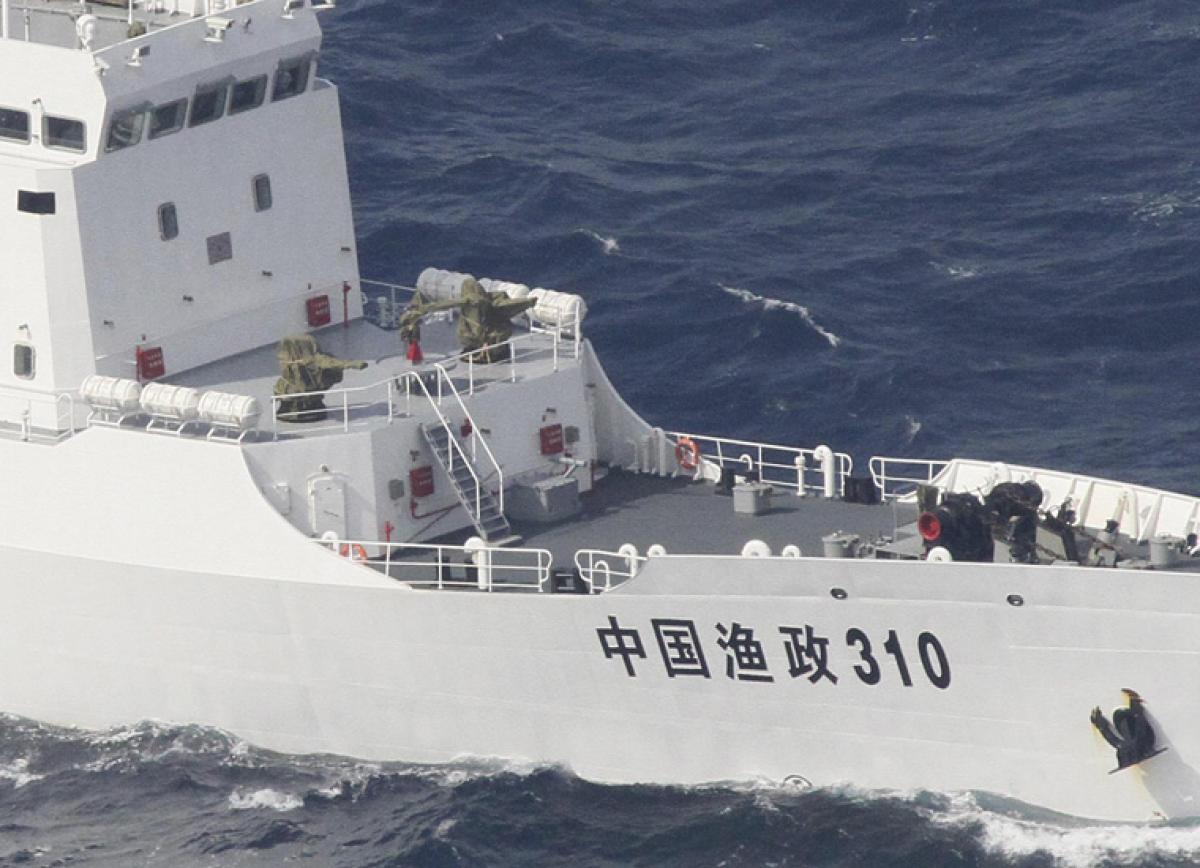

Although nominally a fisheries law enforcement cutter, YZ-310 looks like a warship. Strategist Edward Luttwak has described her as a “long-range corvette.” At 2,600 tons and 354 feet, however, she is much larger than any Chinese ship of this class. With her boxy superstructure and sleek hull, YZ-310 resembles a frigate denuded of her main armaments, painted white. Her only weapons are two inconspicuous 14.5-mm guns, placed just beneath the bridge, framing a water cannon. For all this ship, YZ-310 cost a mere $28 million.4

A Ship Becomes a Celebrity

When YZ-310 was commissioned in November 2010, the Chinese press widely described her as FLE’s “most advanced” law enforcement cutter, which indeed she was by a large margin. She was built to operate in the most remote and most contested sections of the South China Sea. Her first operation, however, took her from her home port in Guangzhou to disputed waters far to the northeast, adjacent to the disputed Senkaku Islands.

In September 2010, tensions arose between China and Japan over Japanese detention of a Chinese fishing trawler that had intentionally collided with a Japanese constabulary ship near the Senkakus. Japan impounded the vessel and detained the crew. China responded by increasing MLE presence around the islets. For symbolic effect, perhaps in part to indulge Chinese patriots, upon her commissioning YZ-310 was ordered to sail directly to the Senkakus to “demonstrate” Chinese sovereignty.5

For her first mission, YZ-310 was commanded by the 52-year-old Chen Lu; his younger brother, Chen Xiong, was first mate. Like many FLE officers, the two brothers came from peasant stock, in their case a Guangdong fishing village. Also typical for the service, Lu and Xiong spent the majority of their lives on deployments. FLE officers are fond of saying that their profession has required them to “cause hardship for their wives, neglect their children, and exhaust their bodies.” Some spend as many as 200 days at sea per year.6

YZ-310 sailed to the Senkakus at a time when Japan still contested Chinese presence near the islets. As she and a second FLE ship approached disputed waters, as many as seven Japanese Coast Guard vessels descended on them. Taking advantage of their superior numbers, the Japanese forces attempted to harry the two Chinese cutters and compel them to retreat. Instead, YZ-310 remained in the area for several days before returning to Guangzhou. The Chinese press lauded the Senkaku operation as a triumph of the “South China Sea spirit.”7

With the 2010 Senkaku patrol, a star was born. When YZ-310 was in port, senior officials visited the ship to toast her celebrity and praise her crew for their service to the cause of Chinese “rights protection.” The ship’s reputation was further enhanced when, in late June 2011, she raced nearly 600 nautical miles through rough seas with a cracked stabilizer fin and malfunctioning engine pump to rescue a Chinese fishing vessel dead in the water near Reed Bank. Despite it being a search-and-rescue mission, Chinese coverage of this event could not divorce it from the geostrategic context: The effort to save the stricken mariners was necessary because “Spratly Island fishing vessels are China’s mobile national territory.”8

The year 2012 marked an aggressive turn in how China pursued its claims to land and sea. YZ-310 was at the center of much of the action. On 10 April, Philippine sailors operating from the frigate Gregorio Del Pilar attempted to detain a number of Chinese fishermen active in the lagoon of Scarborough Shoal. During the course of the encounter, the fishermen alerted Chinese authorities ashore of their predicament. Orders were quickly sent to two nearby CMS vessels, which arrived on the scene in time to prevent the arrests by positioning themselves in between the Gregorio Del Pilar and her captives. The Chinese fishermen were soon released, but a two-month “standoff” ensued, ultimately ending with Chinese control over the feature.

Protecting Chinese fishermen operating in disputed waters has traditionally been a core FLE function. However, in the most dramatic confrontation in recent memory, CMS was the hero. On 16 April, the Ministry of Agriculture—presumably with at least tacit approval from senior Communist Party leaders—decided to insinuate FLE itself into the crisis. At an 0900 meeting, Wu Zhuang issued orders to send YZ-310 to Scarborough Shoal. Chen Lu received a call and sprang into action to replenish his ship in preparation for the deployment. Forty-eight hours later, they departed Guangzhou.9

YZ-310 arrived at Scarborough Shoal on the afternoon of 20 April. At a press conference, Lieutenant General Anthony Alcantara of the Northern Luzon Command revealed the sudden appearance of a “huge” new Chinese vessel. By this time, three of the original 12 Chinese fishing vessels had returned to the feature. YZ-310 lingered on the scene for several days, sending small boats into the lagoon to check on the Chinese fishermen, provide them with fuel and other provisions, surveil the Philippine boats that were also present, and, on 28 April, unfurl a Chinese flag above one of the larger rocks.10

Guardian Angel of the Trawler Fleet

Soon after her departure from Scarborough Shoal, YZ-310 played the starring role in an incident that took place in another part of the South China Sea. At 0940 on 18 May, while sailing between two Chinese installations in the Spratlys, YZ-310 received an urgent message from commanders ashore. Five Chinese fishing trawlers operating off Vietnam’s coast (11°22’N, 110°45’E) were being tracked by several Vietnamese “gunboats.” Since the trawlers were 50 nautical miles within China’s “traditional border” (i.e., the “nine-dash line”), their presence there was legitimate under Chinese law. YZ-310 was ordered to the scene to protect them. During the 140-nautical-mile voyage, her crew received orders to abort the mission because the Vietnamese vessels had given up their chase: the big cutter’s reputation had apparently preceded her.11

Two months later, YZ-310 was once again called on to provide escort for Chinese civilian mariners operating in disputed waters. On 15 July 2012, a flotilla of 29 fishing trawlers from Sanya city (Hainan), accompanied by a 3,000-ton support ship, arrived off Fiery Cross Reef in the Spratlys. They were met there by YZ-310, ordered to protect them during their five to ten days of night fishing, which took place without incident. Widespread Chinese press coverage, made possible by journalists embedded on the support ship, left no doubt that this operation was almost purely a political act.12

YZ-310’s reputation as the “savior” (baohushen) of Chinese fishermen was further enhanced in early 2013. This time the adversary was not the Philippines or Vietnam, but Indonesia. While China and Indonesia do not contest territory in the South China Sea, China’s nine-dash line overlaps with Indonesia’s Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), resulting in a maritime boundary dispute. This has led to periodic confrontations. For instance, on 23 June 2010 two FLE ships blocked efforts by several Indonesian naval vessels to detain crews from three Chinese fishing trawlers operating in the rich “southwest fishing grounds” (4–6°N, 109–112°E).13

The incident that took place in March 2013 is much less well documented by Chinese sources. One authoritative article simply states that FLE “successfully rescued one Chinese fishing vessel and nine fishermen that had been detained by an armed Indonesian ship.” A firsthand Indonesian account unearthed by Australian Defence Force Academy researcher Scott Bentley indicates that the Indonesian Coast Guard vessel Hiu Macan 001 detained the crew of a Chinese fishing trawler operating in Indonesia’s EEZ. As the vessel was returning to Indonesia, YZ-310 caught up—demonstrating the practical value of her speed—and demanded that the Chinese detainees be released. Citing “consideration for the safety of his crew,” the captain of the Hiu Macan 001 submitted to the Chinese demands. In this act of coercion, YZ-310 appears to have jammed the communications of the Indonesian vessel, isolating her crew from any possible support.14

In an interview given two years earlier, YZ-310 skipper Chen Lu explained the attitude necessary to rescue Chinese fishermen attacked or detained by foreign forces. “Rescuing Chinese fishermen is a contest of nerve (danliang). In many cases, our weapons cannot compare with those of the adversary. But I always believe that justice is on our side.” This, of course, is an oversimplification. FLE vessels have explicit action plans for such contingencies. Moreover, Chinese skippers are not alone out there. Chinese MLE vessels conducting “rights protection” operations are in frequent contact with commanders ashore. Images and video footage captured by on-board cameras are transmitted directly to command centers in Guangzhou and Beijing. In the words of one FLE officer, this information “is provided so superiors can conduct real-time command.”15

The next few months, which would be YZ-310’s last with FLE, were equally busy, if less dramatic. In late April 2013 the vessel departed Sanya, Hainan, for another sovereignty patrol to the southwest fishing grounds. In May, YZ-310 arrived at James Shoal, located within Malaysia’s EEZ. While floating above the feature, which is submerged beneath at least 60 feet of water, an “investigation group” from Sansha City (Woody Island) held a ceremony. Led by Mayor Xiao Jie, they declared their willingness to use their “lives and fresh blood” to defend their country’s “sovereignty and dignity” and to use their “wisdom and sweat to build a beautiful and affluent Sansha.” Though Mayor Xiao and his colleagues could not have known it then, YZ-310 would someday be asked to play a much more direct role in helping them realize these ambitions.16

Oblivion . . . and Resurrection?

In July 2013, China formally established the China Coast Guard (CCG). This meant the dissolution of FLE, CMS, and two other MLE organizations, whose personnel and assets were “integrated” into the new agency. The need for reform of China’s fragmented MLE system had been recognized for well more than a decade; now the Chinese government, under new leader Xi Jinping, would actually attempt it.

The reform was not good for FLE, or its famous ship. Since the CCG would fall under the authority of the State Oceanic Administration and the Ministry of Public Security, FLE would be uprooted from its place in the Ministry of Agriculture, its senior officers relegated to lesser roles in the new bureaucracy. Now a part of the CCG, YZ-310 could no longer claim any superlatives. She was a single ship within a fleet that would soon to expand to colossal size, with individual vessels as large as 12,000 tons.

For all these reasons, the “integration” of YZ-310 into the CCG meant her retreat from the public eye. She was painted with CCG colors and given the pennant number 3210. In July 2013, she joined CCG-3368 and CCG-3175 (both formerly CMS) on a mission to Scarborough Shoal. They had been sent to relieve two other cutters that had been blocking Philippine access to the feature for more than a month. Chinese journalists covering the mission remained on board CCG-3368, their reports hardly mentioning the most illustrious member of the flotilla.17

From May to July 2014, the China National Offshore Oil Company (CNOOC) navigated an oil rig (CNOOC 981) to disputed waters southwest of the Paracel Islands. Vietnam immediately responded by sending a number of coast guard and fishing vessels to contest its presence. To protect the rig, China deployed dozens of vessels of its own, the majority being elements of the CCG. CCG-3210 participated in its defense. However, only the Vietnamese cared to notice this.18

By 2015, Chinese policymakers had made other plans for CCG-3210. The CCG had grown to such immense proportions that it no longer really needed the vessel. But Sansha did. In mid-2012, officials upgraded the administrative status of Sansha (population approximately 1,000) to a municipality and gave it an energetic mayor with a strategic vision. Sansha City is responsible for administering great swaths of space within the nine-dash line, including the Parcels, Scarborough Shoal, and the Spratlys. Like other coastal “cities,” it needed its own MLE forces. Given its geography, these forces had to be large and capable.19

In May 2015, CCG-3210 was shorn of her coast guard colors, stripped of her guns, and delivered to Sansha City authorities. She was given a ghoulish new name: Sansha City Comprehensive Law Enforcement Number 1. Official accounts listed her as 320 feet in length, suggesting, if true, that during her refitting she lost more than just her dignity.20

Her first mission was a banal event. On 24 May she departed Woody Island for Macclesfield Bank, where she cracked down on Chinese fishing vessels violating the annual fishing moratorium, replenished a CCG vessel there on patrol, and surveyed fisheries resources. Senior leaders from Sansha, including Mayor Xiao Jie, were on board for the mission and posed for numerous photos, despite suffering from seasickness. A day later she departed for Wenchang in Hainan. Notwithstanding this modest beginning, Chinese sources clearly indicate that in her new incarnation YZ-310 will be expected to play a role in China’s “rights protection” struggle in the South China Sea and that Sansha authorities aspire to patrol the Spratlys.21 Now that she has once again become the most advanced cutter in her service, we may expect that her civilian owners will ask her to seek glory through combat with foreign aggressors, and that Chinese reporters will be asked to chronicle these exploits. The history of this ship is far from over.