Second Prize, General Prize Essay Contest

d and Axis powers cemented the technological innovations of the preceding interwar period and marked a revolution in military affairs. The technologies that shaped the war—submarines, air power, and armor—had been around since World War I. The architectural linkage of existing technologies and tactics in novel ways produced a doctrinal shift in the way war was fought.1 The militaries leading the changes in particular fields—the Japanese and Americans with carrier aviation, the Germans with armored warfare and undersea warfare, or the British in electronic warfare, for example—also reshaped their service cultures and identities. Those defense organizations, in striking parallels to the present day, managed to innovate during this period “in spite of low military budgets and considerable antipathy towards military institutions in the aftermath of the slaughter in the trenches.”2 The changes were wrought by bold officers with prescient visions of the future against a conservative bureaucracy. Lieutenant Hugh Williamson, a British aviator, recorded after his failed attempt to convince the British Admiralty to build an aircraft carrier in 1912:

Prior to the First World War, the navy had had no war experience for a very long time; and a long peace breeds conservatism and hostility to change in senior officers. Consequently, revolutionary ideas which were readily accepted when war came, were unthinkable in the peacetime atmosphere of 1912.3

What the U.S. Navy lacks today is not the technology, but the ability to grasp the full potential of autonomous systems and how they could reshape how we steam, clean, operate, and fight. Equally important is the awareness that our adversaries can and are exploiting them as well. Autonomous systems have the potential to transform the American naval officer from a technical battle manager to a cognitive warrior—once we expand our definition of autonomy. Under the present framework, broadly outlined in the Unmanned Systems Integrated Roadmap, autonomy is limited solely to unmanned systems, with an emphasis on intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance operations.4 All the systems proposed are outside the lifelines of our ships. Autonomy can and should be much broader than this, and fits better on a spectrum of human/machine interaction than in a tidy, limiting definition. Coupled with the notion that advanced warfare is proceeding into the cognitive realm, we shall consider this marriage as “omnispatial” warfare.

Identity Crisis

Historically, nations build navies to project power far from their shores, protect maritime commerce, and defend the nation. Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Jonathan Greenert’s Sailing Directions, a concise summation of the U.S. Navy’s strategic trajectory and missions, reflects that heritage. Admiral Greenert asserts that the Navy’s core responsibilities and mission are to “deter aggression and, if deterrence fails, win our Nation’s wars. . . . With global partners, protect the maritime freedom that is the basis for global prosperity.”5 That statement usually manifests itself in the presence of a competing power and builds the foundation for the Navy’s identity and service culture. A close look at the writings of naval commanders during World War II reflects the Navy’s identity at such a time: Defeat the Axis powers at all costs. Stories abound of officers turning their ships toward the enemy, whatever the odds, to press home the attack. Then, during the Cold War, our naval identity coalesced around two broad themes: the carrier battle groups and their likely slugfests in the North Atlantic and Mediterranean, and the relationship between submarines and strategic deterrence, both in hunting the Soviets and sending our own warheads to sea. The drumbeat of combat readiness and naval tactics in defeating the Soviet Union pervaded our naval culture. The Soviet Union provided a focus against which the Navy could assess its readiness.

Following the fall of the Soviet Union, the focus on combat evaporated, and our leaders found themselves able to relax a bit from the rigors of maintaining combat readiness. The floodgates opened, with greater emphasis on other matters, such as new theories, and a proliferation of Navy missions. In a striking parallel, noted naval historian Andrew Gordon relates the slow decline of British naval power in the second half of the 19th century and early 20th century under similar circumstances. Without major competition at sea, the Royal Navy began to adopt greater regulation and reliance on signals as a means to replace the retiring leaders with combat experience. The empirical evidence of how to win in the Nelsonian era had been traded for untested theory. Meanwhile, new technologies—sail to steam, larger guns, fire control, torpedoes—were changing the face of battle. After nearly a century of stultifying bureaucracy, many British senior officers were so used to rigidly controlled maneuvers from the top down that when the big test for the Grand Fleet came at the 1916 Battle of Jutland, the British could not match German tactical efficiency and too many Royal Navy battlecruisers met spectacular ends.6 The U.S. Navy, now three generations removed from leaders with significant naval-combat experience in World War II, Korea, and Vietnam, is arguably in an eerily similar predicament to the Royal Navy when it entered World War I.

The absence of a naval peer competitor since the Soviet collapse in 1991 has created a crisis of identity for the Navy. With no adversary fleet to measure against until the recent rise of China, the Navy has lurched from one mission to the next as very broadly expressed national objectives dictated, developing systems and weapons to fill niche capabilities in a struggle to remain relevant. The war on terrorism did nothing to shape a new, singular naval identity. Our forces spent 13 years in support of land operations. Our sailors went ashore and our ships bombarded targets—a vital aspect of our service to the nation, but not the core purpose of a navy in the sense of Mahan or Corbett. Those deployed continued conducting peacetime missions: freedom-of-navigation patrols, foreign port visits, intelligence collection, and suppression of piracy and smuggling. The way we saw ourselves and how we would fight had still not evolved beyond the sudden end of the Cold War. The weapons, missions, and the way we operate have not changed appreciably, despite the steady increase in “sloganeering,” as retired Marine Lieutenant General Paul Van Riper so aptly terms it.7 Current concepts, such as Air-Sea Battle, simply pair our current, shrinking capabilities to overcome a current threat. The necessity to “fight tonight” created a mindset that could be catastrophic in the future without a reconsideration of how the Navy can be used to better achieve our national objectives in the coming age of robotic warfare.

The growth of the Chinese navy, the resurgence of an old foe in Russia, and myriad other naval threats worldwide lead down several paths that could potentially result in our own Jutland. Worse yet, daily communication from naval leaders to the Fleet indicates their emphasis, such as preventing sexual assaults and alcohol-related incidents. These areas are immensely important for individual and unit readiness, but conspicuously absent is a concomitant clarion call for Fleet combat readiness. The Navy has sloganeered our core responsibility of fighting and winning our nation’s wars into the tenets of Warfighting First, Operate Forward, and Be Ready.8 Sailors and officers likely do not fully grasp the daily, tactical-level implementation of these tenets, which is the crux of our identity problem. Compounding this is the growth of disparate warfare communities within the Navy with no methodical, explicit connection to the Navy’s core identity. The solution lies in a strong effort to unite the naval forces paradoxically under a new focus on autonomy.

Autonomy and Its Systems

Autonomy and autonomous systems are far from new. Only the shortsighted correlation of autonomous systems with unmanned systems has created the false sense that we are in the opening stages of a new and different revolution in military affairs. Stepping back to a far broader definition, autonomy can be defined as the automation of a specific function. In the Age of Sail, for example, attacking other ships required making physical or near-physical contact with your ship in order to board Marines or pour broadsides into the enemy hull. The invention of torpedoes was an automation in that regard, replacing a primarily human-driven evolution with a new, lethal machine. It had the same end result, sinking an enemy ship, but without the need for close-quarters combat. We continually invent new weapons and sensors to automate formerly human functions and gain greater range in achieving mission accomplishment: Radars extended the search range and accuracy in scouting, hard-to-detect submarines enabled surprise in attack, and steam engines fundamentally altered naval maneuver.

Not all automations were technological. Continuing the historical parallel with the Royal Navy, Nelson’s promulgation of fighting instructions and frequent discussions with his captains created an operational identity and yielded greater unit-level autonomy: initiative without retribution. Nelson and his captains grasped one overriding British strategic goal of destroying the French fleet, even when it had superior numbers. This, coupled with the simultaneous reduction in communications, gave greater autonomy to his captains and enabled his fleet to win smashing victories over French forces at the Battles of the Nile and Trafalgar.9 A well-defined identity and autonomy in command gave the British the decisive advantage.

Thus, autonomy and initiative deserve a broader treatment than the Navy now gives them. Most current programs involving autonomous systems follow the Unmanned Systems Roadmap 2013–2038, which focuses on off-board unmanned systems. These systems are often designed to reduce the risk to human operators or provide a greater or more durable capability than a human system could provide. But these programs simply relocate the human operator farther from risk, erroneously conflating unmanned with autonomous. This mindset curtails the benefits of autonomous systems. It is the logical fallout of our corporate thoughts on autonomous systems, which see unmanned systems operating at discrete levels of autonomy instead of considering the possibility of an autonomous spectrum. The Defense Science Board chastised the Department of Defense for this view in 2012, stating that the studies on levels of autonomy “are counterproductive because they focus too much attention on the computer rather than on the collaboration between the computer and its operator/supervisor to achieve the desired capabilities and effects.”10

‘A Better Grasp’

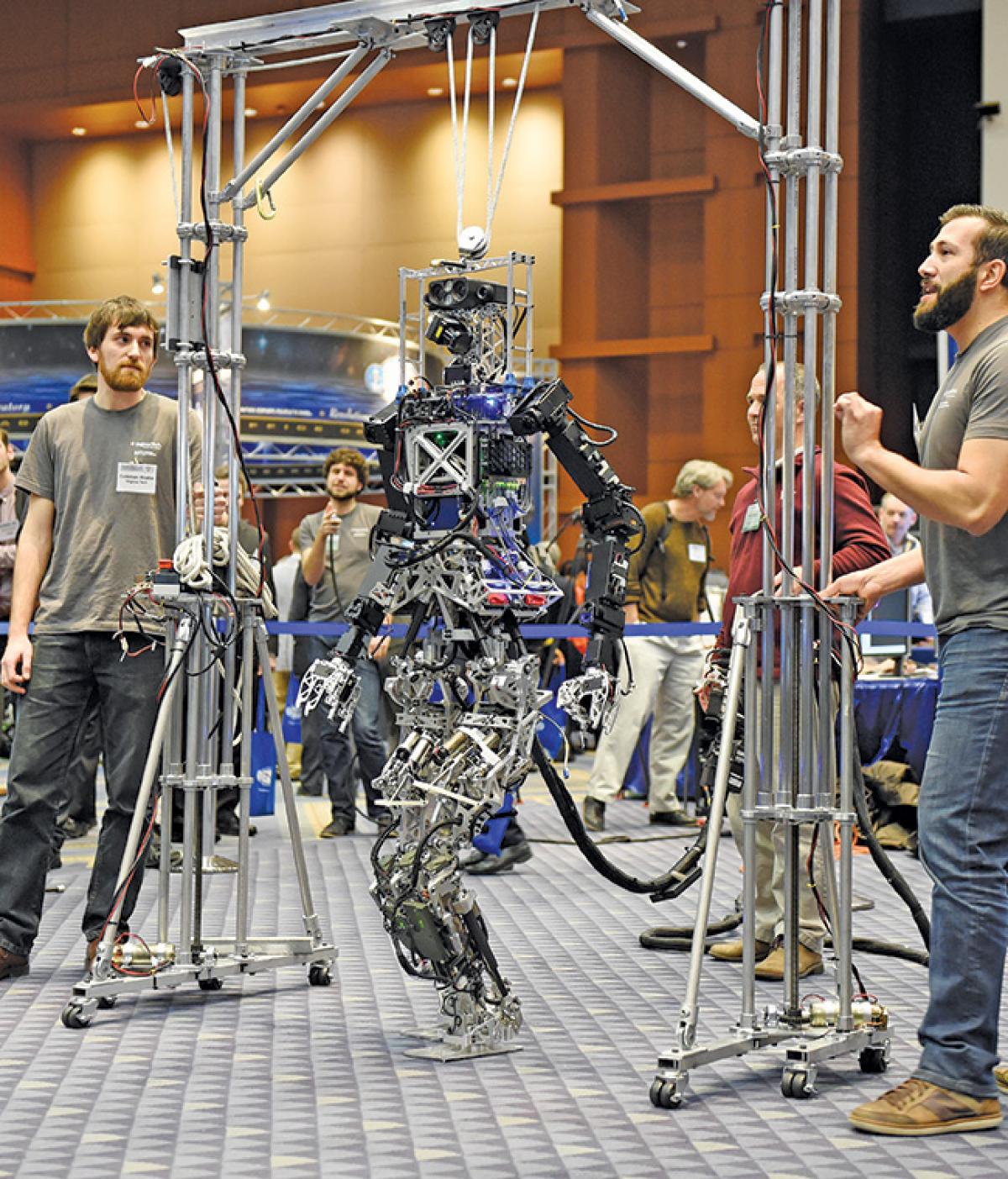

Autonomous systems in the Navy must be treated in a way consistent with the Defense Science Board’s recommendation. Computers and technology have the potential to free our officers and sailors of the cognitive burdens that slow our decision-making while simultaneously giving our leaders a better grasp of the situation. The nascent field of cognitive computing holds the promise of giving individual commanders the sum total of naval experience at their fingertips, with the ability to analyze new information and think as humans do. John Kelly and Steve Hamm relate a similar concept of cooperation between doctors at the Cleveland Clinic and IBM’s Watson computer in battling cancer, with extraordinary results.11 Additionally, technology provides a way to potentially liberate the sailor from the endless dull, dirty, and dangerous jobs that come with maintaining a vessel of war. It seems a simple stretch to have a modified iRobot Roomba vacuuming robot cleaning the decks or a larger autonomous system freeing sailors from “cranking” in the scullery to clean dishes, for example.

Away from the ship, autonomous systems need not conform to a discrete level of autonomy. They should aid commanders in executing the various warfighting functions: command-and-control, maneuver, fires, intelligence, logistics, and force protection.12 Autonomous, unmanned systems have the ability to fundamentally alter how to approach these areas of warfighting. The possible examples abound: cheap, optionally expendable swarms for force protection, optionally manned surface vessels, predictive decision aids to assist in swift action, and so much more. Former Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel viewed these technologies as key areas of future DOD investment.13 The question should never be if an unmanned system can replace an existing system, but rather, can the autonomous system complement manned systems to help the commander do his or her job better. The best advances would allow our commanders to focus on warfighting instead of the minutiae of task-steps that must be performed to fulfill it. Delivery of payloads for maximum effect at the unit level should be the foremost concern—victory depends on it.

Battlespace(s)

For thousands of years, humans fought each other on the ground or riding the waves. In looking for new ways to defeat conventional forces, naval innovators took to the undersea and air domains, in the 1700s and 1900s, respectively. Now we have entered the electromagnetic, information, and cyber domains in the quest to achieve our objectives. Periodically, nations have articulated operational strategies with the express intent of changing minds. While this statement could be brushed off as the logical conclusion of a well-performed center-of gravity analysis, the real objective behind these operational strategies—strategic air power, effects-based operations, psychological operations, and many other temporarily fashionable strategies—is to expand the battlespace into the cognitive domain. However, few have gone so far as to call an adversary’s mind a tactical-operational level center of gravity. If they did, the operational strategy to eliminate it rested solely in the physical domain, generally with kinetic operations.

Colonel John Boyd, the mastermind behind the observe-orient-decide-act (OODA) loop, came the closest to identifying cognitive warfare as a unique domain.14 Success in battle, at all levels, lies in the relative difference between our and our adversary’s OODA loops: Speed up ours and slow down theirs. With the expansion of warfighting effects into non-kinetic realms, the time is ripe to articulate what warfare in the cognitive domain must look like. The sum of operations, whether aimed for cognitive, asymmetric, or more traditional effects, represents a shift in the Clausewitzian, subjective nature of war. Let us call it omnispatial warfare.

As the Latin roots reveal, omnispatial warfare means conducting warfare across all domains simultaneously to achieve the objective. No longer will electromagnetic or cyber effects be solely supporting actors to kinetic means. Mutually enhancing tactics and operations carried out simultaneously in all of the domains represent a new, broad, and difficult front to counter. At the grand strategic level, this represents a whole-of-government approach to shape the conflict from beginning to end and has historical precedent. However, applying a similar concept at the tactical or operational levels of war is relatively new. What could omnispatial war look like?

At these levels, advances in information operations and cyber warfare make the future particularly exciting. Expert employment of electromagnetic maneuver warfare can create dizzying effects on the adversary’s tactical picture, by nullifying his resources for precision navigation, communications, and intelligence gathering. Offensive cyber operations can cause major equipment damage, data poisoning, and potentially even allow for cyber-commandeering of an adversary’s ship, aircraft, or command-and-control capabilities. Cheap, optionally expendable systems will help an individual unit commander create his or her own tactical swarm, whether for attack or force protection.

The point of all this? Create enough chaos and confusion in the right places, upon the right people, at the right moment, to significantly slow or stop their intended actions. Should the conflict turn hot, the expansion of non-kinetic effects and use of kinetic means would present multiple challenges for enemy commanders at all levels, overwhelming their brain capacity for rational decision-making. Psychologists understand this as cognitive overload. Our future officers and sailors, through autonomous systems, will become cognitive warriors, able to employ a variety of tools across multiple domains to achieve superiority and victory on the battlefield.

Achieving the Omnispatial Vision

Omnispatial warfare lies at the nexus of the Navy’s identity and autonomous systems. Grasping the nexus will not be easy amid significant bureaucratic inertia. Bureaucracies tend toward doing what they know how to do and reject ideas or new operational ways and means that threaten their established norms. The naval service is no exception. For the Navy to emerge from the doldrums of identity and embrace fundamental change in how we fight, the Chief of Naval Operations and his trusted staff must make a significant investment of political and real capital to chart a new course with two broad thrusts.

First, the Navy must make autonomous systems ubiquitous. To understand the limits of current efforts that consist of a mere handful of test systems spread across the Fleet, consider some basic facts. The littoral combat ship (LCS) has a payload capacity of 180–210 tons, depending on the variant. The joint high-speed vessel (JHSV) can carry 600 tons. By comparison, a single Insitu ScanEagle unmanned aerial vehicle weighs a minuscule 0.022 tons, and a Bluefin Robotics 12S unmanned underwater vehicle tips the scales at 0.213 tons. The orders-of-magnitude difference between the weight of the unmanned systems and the payload capacities, strictly in a qualitative sense, indicates just how many of these vehicles a single LCS or JHSV, for example, could carry. Quantity now becomes a quality all on its own. The CNO’s wise emphasis on payloads over platforms reveals just how powerful a ubiquity of unmanned systems could be for the Navy and the nation.15 But to see and exploit the advantages, the Navy must start fielding autonomous systems rapidly and in large numbers. Encourage officers and sailors, not contractors, to use them by giving them new tasks and learn from them. Give the Fleet easier and widely distributed avenues to communicate ideas on how technology could help them do their jobs better—automating some of their workload. Allowing today’s officers and sailors to problem-solve in this fashion will produce a cadre of future leaders who are able to think creatively and critically, which are the qualities needed for omnispatial warfare.

Second, the Navy must enhance the art of strategic communication to the Fleet. Service culture is shaped by daily engagement from senior leaders. Every sailor understands the issues surrounding alcohol-related incidents and sexual assaults because our leaders reinforce them almost daily. The Navy must initiate an even greater effort to make every single sailor understand that warfighting is our core mission. Our foremost responsibility to the nation is to be combat-ready. That is the message to be driven home on a daily basis. Strategic communication is not easy. It requires synchronized, cascading messages from the top. It cannot be reduced to sloganeering, as messaging is apt to become in the digital age. Imbuing every sailor with a sense of shared identity and a single goal—readiness for omnispatial warfare—constitutes the best force multiplier. Many of our greatest combat leaders throughout our history recognized and harnessed this to achieve success. We can do so again.

Bureaucratic inertia must not impede a transformation into the robotic age. To regain a sense of our former selves, the Navy must wholeheartedly embrace the panoply of autonomous systems, from which a new warfare identity can emerge. The identity will grow from the idea that our sailors and officers are not technical battle managers, but cognitive warriors, capable of delivering effects omnispatially against an adversary across the spectrum of conflict. What an asset to our nation that will be.

1. Terry Pierce, Warfighting and Disruptive Technologies (New York: Frank Cass, 2004), 16.

2. Williamson Murray and Allan Millett, Military Innovation in the Interwar Period (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 3.

3. Geoffrey Till, “Adopting the Aircraft Carrier,” Military Innovation in the Interwar Period, Williamson Murray and Allan Millett, eds. (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 192.

4. U.S. Department of Defense, Unmanned Systems Integrated Roadmap FY2013–2038 (Report 14-S-0553), 1, http://www.defense.gov/pubs/DOD-USRM-2013.pdf.

5. U.S. Department of the Navy, “CNO’s Sailing Directions” (2014), http://www.navy.mil/cno/cno_sailing_direction_final-lowres.pdf.

6. Andrew Gordon, “Military Transformation in Long Periods of Peace: The Victorian Royal Navy,” The Past as Prologue, Williamson Murray and Richard Hart Sinnreich, eds. (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 150–169.

7. Scott Willis, Alex Vlack, and Peter Tyson, “The Immutable Nature of War,” Public Broadcasting Station NOVA, 4 May 2004.

8. “CNO’s Sailing Directions.”

9. Wayne P. Hughes Jr., Fleet Tactics and Coastal Combat (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2000), 55.

10. The Role of Autonomy in DoD Systems (Washington, DC: DOD Defense Science Board, 2012), 4.

11. John E. Kelly and Steve Hamm, Smart Machines: IBM’s Watson and the Era of Cognitive Computing (New York: Columbia University Press, 2013).

12. U.S. Marine Corps, Marine Corps Operations (MCDP 1-0), B-3.

13. Sandra Erwin, “Hagel: DoD Will Invest in ‘Game Changing’ Technologies,” National Defense, 16 November 2014.

14. John R. Boyd, “Destruction and Creation,” http://www.goalsys.com/books/documents/DESTRUCTION_AND_CREATION.pdf.

15. ADM Jonathan Greenert, USN, “Payloads over Platforms: Charting a New Course.” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings, vol. 138, no. 7 (July 2012), 16–23.