Every year hundreds of marine mammals are transported by air. This is done for a variety of purposes. While removal from their home environments and transporting is stressful for the animals, travel by air is least harmful.

Globally, airfreight companies and many major airlines offer transit services for a wide variety of animals. Elephants, cattle, horses, and whales are some of their larger “passengers.” In almost every case, flying is preferred to other forms of transport.

In the United States, the governing law is the Marine Mammal Protection Act (MMPA) of 1972 (as amended over the years). Through a permitting process, the MMPA carefully regulates the import and export of marine mammals. The basic intent is to ensure healthy populations of species as well as education of the public.

The permitting process for whales, dolphins, seals, and sea lions is the responsibility of the National Marine Fisheries Service of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (part of the Department of Commerce). The Department of the Interior’s Fish and Wildlife Service has a similar responsibility for other marine populations. Finally, the overall permitting process is monitored by a third federal agency, the U.S. Marine Mammal Commission.

The highest-visibility shipments of marine mammals are those involved with restocking marine-themed amusement parks and aquariums. Surplus animals are moved between parks throughout the world. Two thirds of these theme-park marine mammals were actually born in captivity.

In addition to captive-born specimens, there are those captured in the wild to add to the populations of the theme parks and aquariums. The MMPA stipulates that wild-caught animals cannot come from threatened, endangered, or depleted species.

At the larger marine parks, trained dolphin, seal, and whale shows are very popular with the public—and very profitable for park owners. Unfortunately, there have been allegations of animal abuse that in some cases have led to death and injury for the park personnel who handle these creatures.

There are about 200 marine parks, aquariums, and zoos in the United States that have some marine mammals in their collections. Most assert they are committed to animal conservation and education, and there are governmental regulations as well as voluntary industry standards to monitor care and health.

There are also more than 30 active U.S.-based animal-welfare organizations that want to protect marine mammals from capture and exploitation. Internationally, there is an even larger community of animal-rights groups with the same goals.

It is a difficult situation for parks and marine aquariums that house marine mammals. In general, marine parks offer entertainment while aquariums offer educational experiences. But the distinction is not clear-cut. People who may never have the opportunity to see a marine mammal at close range now have the opportunity to view and learn about them in an aquarium.

The world’s single largest marine mammal population manager is the U.S. Navy’s Marine Mammals Program. It began in 1960 in San Diego and became a “black program” shortly thereafter, only to be declassified in the early 1990s; by the end of that decade the Navy’s animal population was over 140.

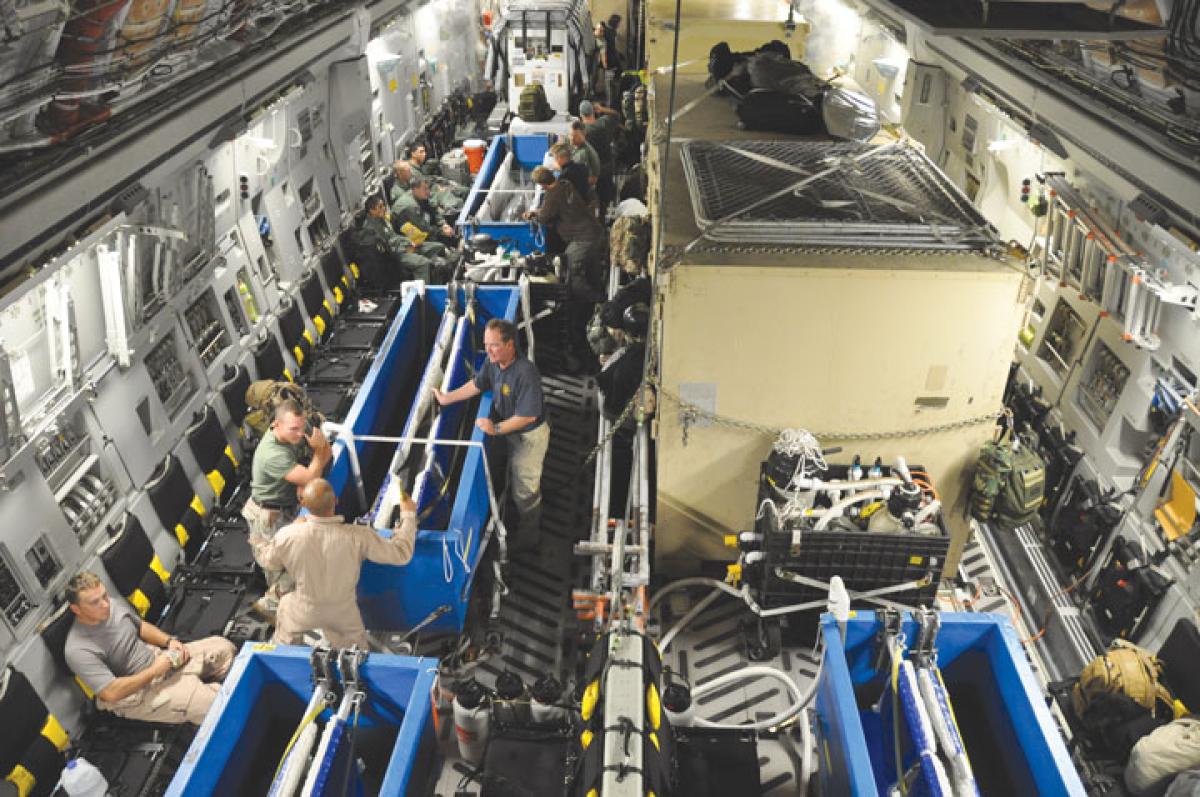

The primary species used in the Navy program are the bottlenose dolphin and the California sea lion. Organized into five teams, they specialize for specific tasks such as mine hunting, seaport protection from underwater swimmers, and ordnance/object recovery. Through use of boats, ships, helicopters, and aircraft, the teams are deployable with only 72 hours’ notice.

The first major deployment of the Navy’s trained marine mammals was during the Vietnam War; since then, they have been put to work in many parts of the world. Despite the protests by animal-rights advocates, national-security requirements are a legitimate reason for the Navy to maintain this capability.

It is clear that the dialogue between the parks, aquariums, the Navy, and animal-rights advocates will continue for some time. However, there is some moderation in sight. It has been reported that the Navy will be phasing out the mammals program in favor of robots over the next few years. Also, some marine parks have closed, so there will be decreasing demand for captured animals. Public criticism has also resulted in the reduction of large marine mammal populations at some of the parks.

But the fundamental disagreements may never be resolved until the last large marine mammal leaves captivity. That is unlikely.