Sometimes in the throes of monthly and bimonthly Proceedings and Naval History deadlines, we lose sight of just how much bigger the U.S. Naval Institute is than any or all of us. And the 15 founding members who convened on the evening of 9 October 1873 by the light of oil lamps in the U.S. Naval Academy’s Department of Physics and Chemistry building probably had no idea that the organization would ever be as influential and relevant as it is today.

By 1873, the bloody War Between the States was a distant memory, having ended more than eight years earlier. Sometime that year Commodore Foxhall Parker, a Civil War veteran himself, is thought to have spawned the idea for “a professional forum similar to the Journal of the Royal United Service Institution.” The U.S. Navy had become a mere shadow of its former self (by some accounts going from 700 to 52 ships within five years after the war), and the innovation that helped the Union emerge victorious had grown stagnant. The global effects from what is known today as the Panic of 1873 (a crisis that spawned what was dubbed the “Great Depression” until the depression of the 1930s overtook that label) didn’t help the Navy’s grave shipbuilding situation. The month before the Naval Institute’s first meeting, a series of bank failures closed down the New York Stock Exchange for ten days, and layoffs spread across the country.

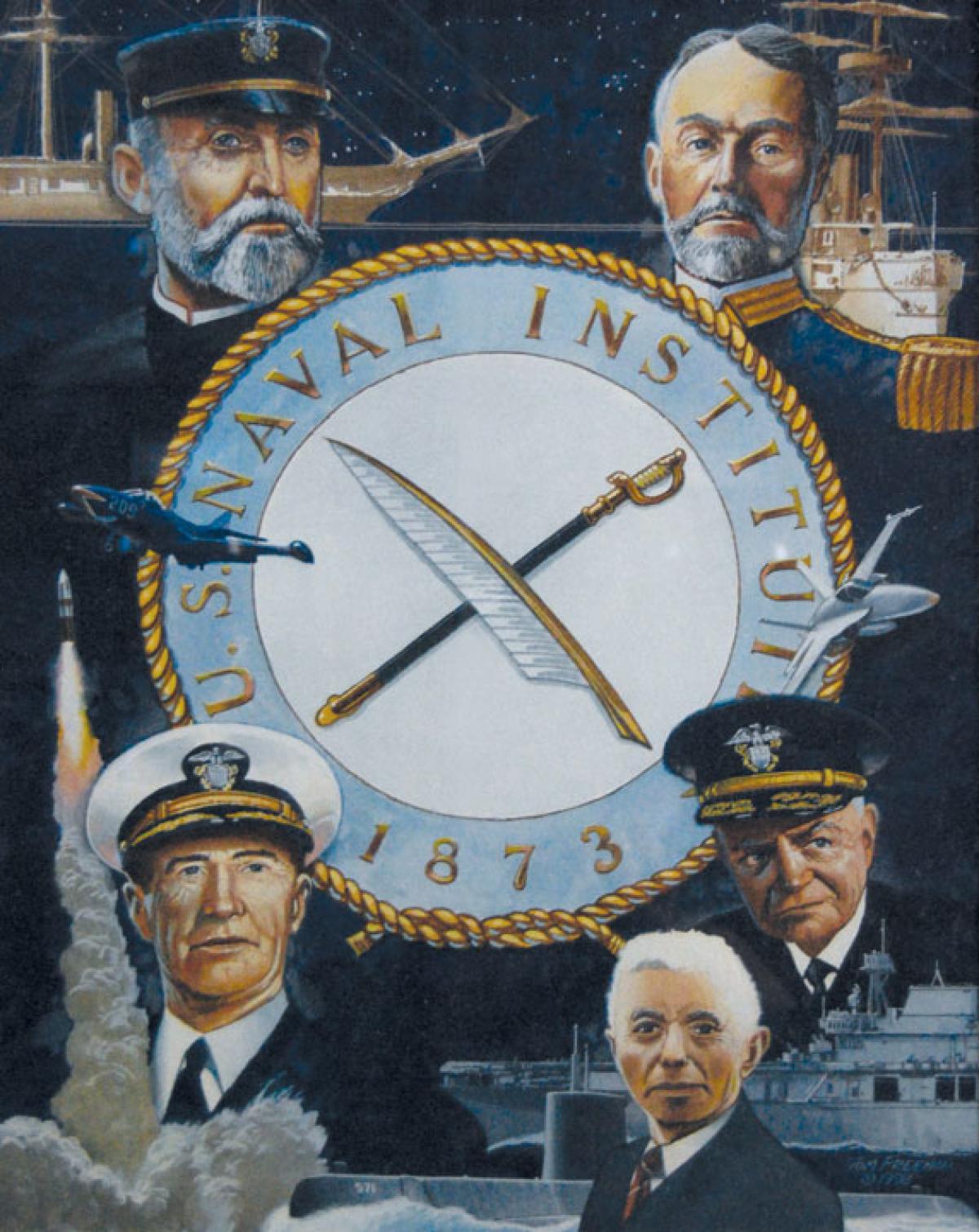

A group of servicemen in Annapolis decided that something needed to be done to reinvigorate and rejuvenate the Sea Services. So under the organizational guidance of Navy Lieutenant Charles Belknap, those original members assembled with their first leader, Naval Academy Superintendent Rear Admiral John L. Worden (pronounced WERE-den, a correction made at a history conference by one of the admiral’s descendants). Worden was best known as the captain of the USS Monitor, the Union Navy’s first ironclad ship that gained fame in the Civil War Battle of Hampton Roads against the former USS Merrimac, which the Confederates had converted to the ironclad CSS Virginia. As fate would have it, one in the group, Commander Samuel Dana Greene, had been Worden’s executive officer and acting commanding officer in the Monitor. The founders also included one Marine officer, Captain McLane Tilton.

The theory that Commodore Parker conceived the idea for this “Society of the Officers of the Navy for the purpose of discussing matters of professional interest” could stem from the fact that Parker himself was the presenter at that first meeting, as he read a paper he had already composed. The topic was the 1571 Battle of Lepanto. The intent may have been to discuss lessons learned from history and apply them to reversing the sorry state of President Ulysses S. Grant’s Navy. While his Lepanto “paper” did not appear in the first volume of what would eventually be Proceedings (it was apparently well received in serial form, published in the Army and Navy Journal), his analysis of the Hampton Roads battle, titled “The Monitor and the Merrimac,” was featured in that initial Naval Institute publication, evidence of the importance placed on the “first battle of the ironclads” to the future of the Navy.

While naval history was prevalent during the presentations and discussions during those early years, and it still is a major part of them today, credit for being the first to confront a real issue and see results was Captain Stephen B. Luce, who read “The Manning of our Navy and Mercantile Fleet” at the Institute’s second meeting in November. It was the first Proceedings article to lead directly to federal legislation for Merchant Marine training, naval apprenticeships, and the opening of the first state maritime school in New York City.

Some young Navy lieutenants who wrote for Proceedings went on to greater things. Ernest J. King, a future Chief of Naval Operations, won the 1909 Prize Essay Contest with a six-point plan to streamline shipboard officer and crew assignments. Three years later, submariner C. W. Nimitz, also a future CNO, proposed to deceive the enemy with “dummy periscopes.”

Thus began a long line of naval thinkers who made contributions that had impact. Through the Spanish-American War, World Wars I and II, the Korean and Vietnam Wars, and Operations Desert Storm, Iraqi Freedom, and Enduring Freedom, the Naval Institute has published enlisted and junior, flag, and general officers, senior government officials, high-level journalists, prizewinning authors, deep-sea and space explorers, filmmakers, and even Hollywood stars and directors with some connection to national defense. Amazingly, the organization has been doing the same thing, as of this month, for 140 years.