It was a beautiful day to be at sea on 20 July 1960 as the USS Observation Island (E-AG-154) barely moved on the sparkling waters off Cape Canaveral under the bright blue dome of a cloudless sky. Nearby, two other ships—the destroyer USS Gearing (DD-710) and the submarine rescue vessel Kittiwake (ASR-13)—also lolled on the placid waters, waiting for history to be made.

Suddenly, less than a mile from the Observation Island, the glassy sea was shattered as a great geyser erupted from the depths, and a large cylinder leaped into the air trailing fire from its base. Sailors watched in awe from the nearby ships as the first Polaris missile ever to be launched from a submarine climbed into the heavens, leaving behind a trail of smoke and a lot of old ideas and pessimistic predictions.

Less than five years before, naysayers warned that such a feat was impossible, that there were too many problems and not enough solutions. They pointed out that a submarine was too unstable a platform for launching ballistic missiles, that nuclear-tipped missiles could never fit into a submarine, that accurate navigation and targeting from beneath the sea was impossible, that the rapid influx of water that would replace a submarine-launched missile would quickly sink the submarine, and a host of other show-stopping difficulties.

But in the USS George Washington (SSBN-598)—the submarine that successfully launched the missile that day—was a factor that the pessimists had failed to consider when formulating their gloomy assessments. Exchanging congratulatory back slaps and enthusiastic handshakes with the sub’s crew members and others in his team was Rear Admiral William Francis Raborn Jr., known to his friends as “Red.”

A U.S. Naval Academy graduate in the class of 1928, Red Raborn proved himself in combat during World War II and successfully held a number of commands, including two aircraft carriers. But these impressive achievements pale in light of his most important contribution to the nation’s defense.

While the development of the Polaris missile and the submarines to launch them involved countless numbers of people, Raborn was the driving force that made these incredible achievements possible, coordinating many diverse elements to solve the myriad problems that stood in the way of success.

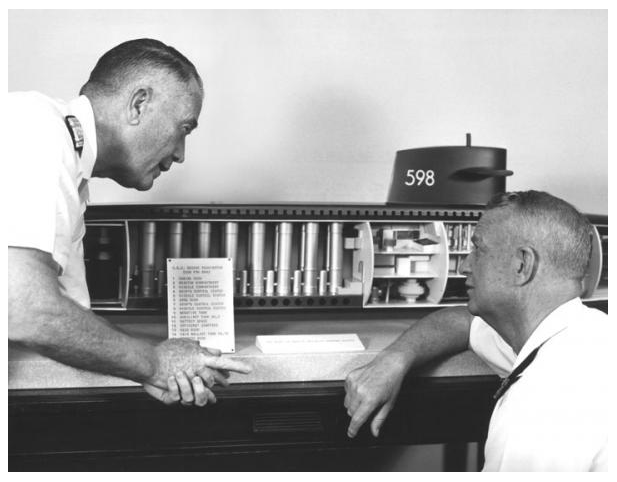

Rear Admiral William F. "Red" Raborn (left) discusses a model of the Navy's first Fleet ballistic-missile submarine USS George Washington with Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Arleigh Burke in 1959. Burke had handpicked Raborn to oversee the submarine-launched missile program. U.S. Navy/U.S. Naval Institute Photo Archive

Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Arleigh Burke had handpicked Raborn to head the “Special Projects Office” in 1955, tasking him with achieving interim capability by 1963 and to be fully operational by 1965. Raborn beat that daunting schedule by five years with the first deterrent patrol under way by November 1960. He had successfully detached the Navy from early attempts (in conjunction with the Army) to accommodate liquid-fueled Jupiter missile technology at sea, opting instead for the less-developed but more promising solid-fuel technology. He also bypassed the planned forerunner of a surface-launched missile and went directly for a submarine launch. Much of his efficiency came from his adoption of PERT (Project Evaluation and Review Technique) methods to greatly streamline the research-and-development stages of the program; those pioneering methods formed the basis of the “Critical Path Method” still used today in many major development projects.

Largely overshadowed by the contemporary and vastly more colorful Hyman Rickover, Raborn is largely forgotten and rarely included in pantheons of naval heroes. Yet his contributions to the Navy and to national defense are among the most important of the modern era, because his leadership provided a vital component to the nation’s nuclear triad at a time when the best hope for survival and ultimate victory in the Cold War was deterrence. It is difficult to imagine an American superpower “fighting” the Cold War without the deterrent capacity offered by Polaris (and later Poseidon) missiles and submarines, and it is equally difficult to imagine these vital components without Red Raborn.