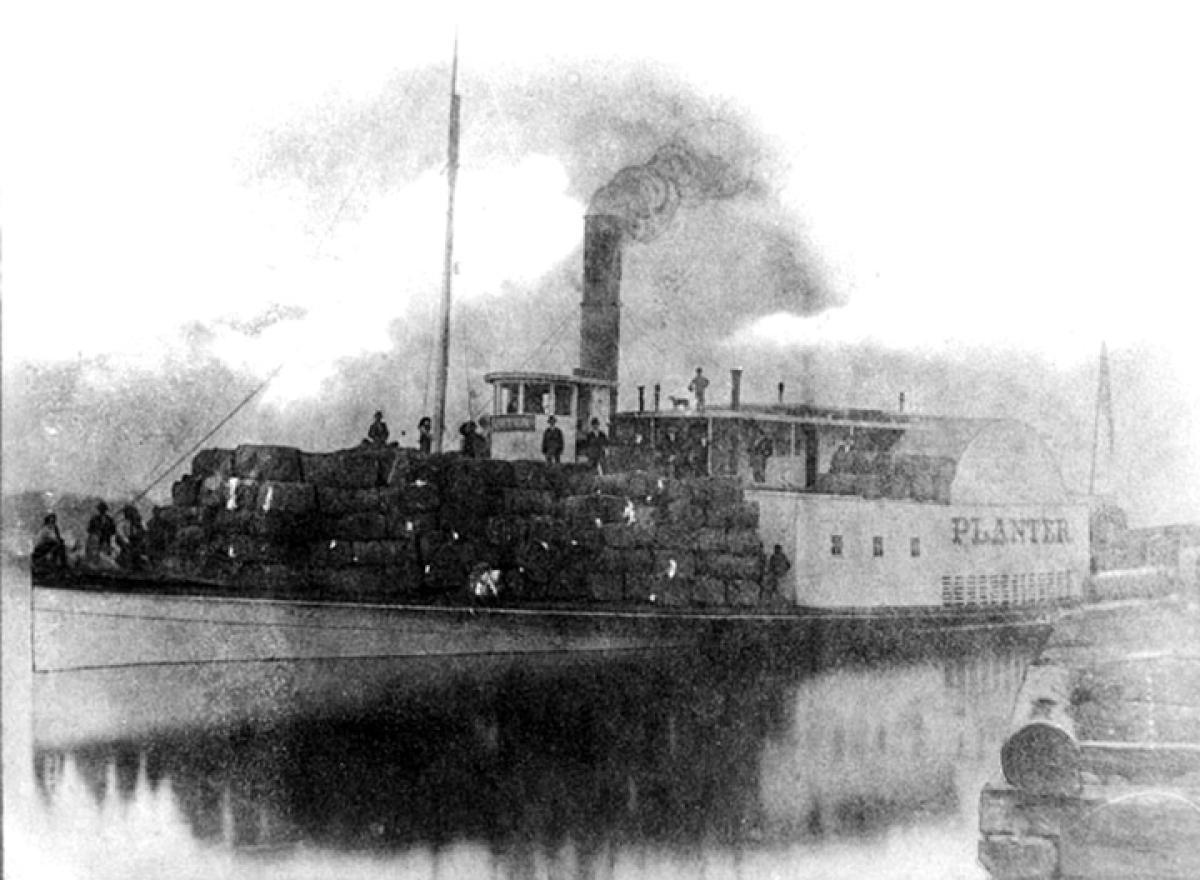

Robert Smalls was born a slave on a South Carolina plantation, and when he turned 12, his master sent him to Charleston to hire out. Smalls worked at various jobs, sending most of his earnings back to his master. He eventually married a hotel maid, also a slave, and in 1861 was hired as a deckhand on the former cotton steamer Planter, then serving as a military transport for the Confederate Navy. He soon proved his worth and was promoted to “wheelman” (actually a pilot, but as an African-American he was not permitted to hold that title).

On the night of 13 May 1862, while moored at Southern Wharf in Charleston Harbor, all three of the Planter’s white officers ignored regulations and went ashore, leaving Smalls and the other slave crewmen alone on the vessel. Smalls waited until 0300, then executed a plan he had been preparing quite some time. After donning the captain’s uniform, he quietly got under way and headed for another wharf, where his wife and children and the families of other members of the crew were waiting. When all were embarked, Smalls pointed the Planter’s bow toward the sea . . . and freedom.

Before they could make good their daring escape, the slaves had to run past five Confederate forts—including the infamous Sumter—and safely navigate through a number of minefields. Armed with the Confederate recognition signals that the careless officers had left behind, Smalls was able to pass the forts without incident, and because he had helped lay the mines, they proved to be no problem either.

Once clear, Smalls steered for the nearest Union Navy blockading ship, the Onward, and hoisted a white bed sheet to prevent being fired on. As he drew near the Federal ship, Smalls raised his hat high in the dawn’s early light and said, “Good morning, sir. I have brought you some of the old United States’ guns, sir!” And indeed he had. Not only was the Planter carrying slaves to freedom and Confederate codebooks, she was loaded with armaments and supplies intended for the Rebel forts. The information that Smalls brought with him about harbor defenses and the like also later helped Union forces capture some key positions in the area.

Smalls not only achieved freedom for himself and the others, but was awarded a healthy sum of prize money as well. But more significantly, he also helped to dispel some of the stereotypical beliefs held by many who felt that blacks were incapable of such daring. The New York Daily Tribune asked, “What white man has made a bolder dash, or won a richer prize in the teeth of such perils during the war?” Two weeks after the escape, Smalls met with President Abraham Lincoln, and the meeting apparently helped persuade the President and Secretary of War Edwin Stanton to permit black men to serve in the Union Army.

Smalls again served as the Planter’s pilot—this time for the Union Navy—and he eventually became her captain. After the Civil War, Smalls purchased the house in which he had been a slave and served as a member of the South Carolina House of Representatives and Senate, eventually moving on to serve as a U.S. congressman.