The Arctic Ocean is the smallest and shallowest (maximum depth, 16,400 feet) of the five oceans. It contains 22 percent of the world’s continental shelves, which comprise almost a third of the Arctic’s seafloor. Those shelves begin at the shoreline, and their outer edges are in water depths from 330 to 650 feet.

The Arctic region is warming more that twice as fast as the rest of the planet. Its ocean is losing permanent ice cover, making more area accessible for longer periods of time. Some estimates state it will be ice-free in the summers within two decades.

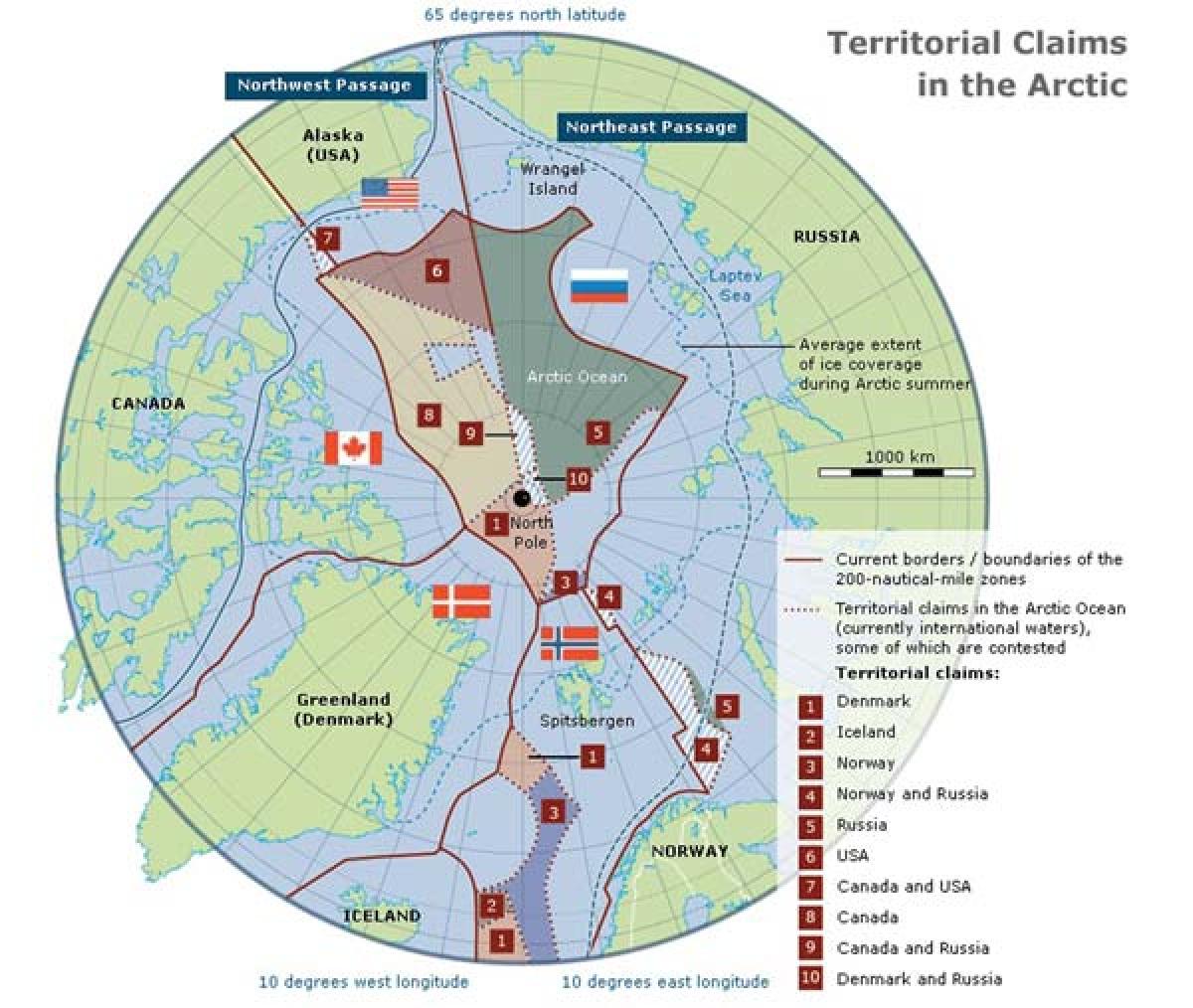

There is an Arctic Council made up of the five nations that border the Arctic Ocean: Russia, Canada, the United States, Norway, and Greenland (an autonomous province of Denmark). The other Arctic non-coastal states of Sweden, Finland, and Iceland also are members. The council is intended to help coordinate member activities and resolve territorial claims in the region. Other nations, such as China, Japan, and South Korea, plus the European Union, have asked to join the council as “permanent observers.”

The United Nations Convention on Law of the Sea, signed in 1984, gives coastal states certain rights within an adjacent 200-mile-wide Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). Among those rights are resources development, maritime traffic monitoring, enforcement against illegal activities, and conservation. While the United States is not a signatory to this treaty, it does generally follow its provisions for continental-shelf activities.

The 200-mile EEZ limit applies to the ocean waters and the seabed; the seafloor limit can extend well beyond that distance, perhaps as much as an additional 200 miles. This added area is termed “The Extended Continental Shelf” (ECS). According to the U.S. Geological Survey, this vast expanse could contain 90 billion barrels of undiscovered oil and up to one third of the world’s natural-gas deposits.

Coastal nations making ECS claims are required to undertake scientific surveys and present their data to the U.N. Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS). This must be done within ten years of their signing the Law of the Sea treaty. The commission then either will approve the claim or request that more data be presented. While not a treaty signatory, the United States is also working on expanding into the ECS at six areas worldwide. The U.S. ECS program is led by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

The galvanizing event in the Arctic Ocean “Race to the North” took place in August 2007. Two Russian Mir submersibles dove 13,980 feet to the “real North Pole” on the floor of the Arctic Ocean and planted Russia’s flag there. That coincided with the Russians’ extended, but not approved, claims to a much greater seafloor area that could include the North Pole. Almost immediately, Denmark (via Greenland) and Canada made similar claims to larger ECS parts of the seafloor out toward the Pole. All those claims are yet to be approved by the U.N.’s CLCS.

Russia already has the world’s largest EEZ—up to 980 miles wide while the global average is about 50 miles. With the Arctic Ocean’s shrinking ice cover, Moscow is making billion-dollar infrastructure investments along the Siberian coast. If Russia’s enhanced coastal-shelf area claims are approved, it will greatly add to the resource wealth of the country’s offshore regions.

The international focus on use of the Arctic Ocean is not only political; it also relates to activities such as fishing and maritime commerce. The majority of the world’s fishing grounds are on continental shelves. A more accessible Arctic will help add that 22 percent to the larder.

A seasonally ice-free Arctic Ocean can cut shipping distances between Asia and Europe by about one third as compared to the Suez Canal route. Russia’s Northeast Passage would be the preferred path, as it is doubtful Canada will permit an international shipping route through its environmentally sensitive Northwest Passage.

The race north is on. New resources will add to our collective wealth if the politics do not get in the way.