David Robinson was a towering figure on the NBA’s San Antonio Spurs—and not just because he is 7 feet, 1 inch tall. As a U.S. Naval Academy midshipman, he won college basketball’s two most prestigious awards (the Wooden and Naismith awards) and made All-American. Nicknamed “The Admiral” because he’d gone to the Academy, he was drafted as a center for the Spurs. But former Lieutenant (junior grade) Robinson credits his days as a Midshipman—and the two years he spent on active duty as a Civil Engineering Corps (CEC) officer—for imbuing values that would play well on the court for the rest of his career. Here’s his story.

Okay, I played basketball at the Naval Academy, so it’d be easy to see how my experiences in uniform helped me when I turned pro and became a center for the San Antonio Spurs. But the truth is, that’s only a part of it. The time that I spent on active duty as a CEC officer has loomed large in my life all these years as well.

As a matter of fact, I think about all my time in uniform as a single unit. I applied to the Naval Academy because it offered the best of two worlds: it had one of the country’s best engineering schools, and I could play Division I basketball. My dad had been in the Navy, as a chief sonar technician. The decision was easy.

I was fortunate enough to succeed in basketball, but I was just as proud of having done well in mathematics and science, which took a lot of studying and hard work. When I received my commission in 1987, I was sent to the CEC Officer School at Port Hueneme, California.

Under a special program, I served two years on active duty, most of it as resident officer-in-charge of construction at the Naval Submarine Base at King’s Bay, Georgia, and then left the Navy as a lieutenant (junior grade) to go to the Spurs. I spent another four years in the Naval Reserve, attending meetings and summer training.

Between my Academy days and my time on active duty, the Navy taught me several things that shaped my approach to basketball, business, and family life. The number-one lesson was the importance of teamwork. Out in the civilian world, people usually worry about themselves. In the military, if you don’t look out for one another, it might cost lives.

Being able to work as part of a team is a rare asset in professional sports. The Spurs won two NBA championships when I was there, and two more after I became an owner. Our coach, Greg Popovich, was a U.S. Air Force Academy graduate who understood the importance of teamwork. His main catchphrase was, “Keep pounding on the rock.” You can hit it 99 times without a crack, but on the 100th blow, it will break into pieces.

Having been in the Navy also helped me understand what a great opportunity—and a blessing—it was to be playing in the NBA. Although I’d done well on the Academy’s team, I acquired a feeling of responsibility that I had to succeed—for the team, the coaches, and the fans. I didn’t take anything for granted.

At an NCAA tournament, Brent Musburger, the CBS sportscaster, nicknamed me “The Admiral” because I was playing for the Naval Academy, and the moniker stuck through my 14 years in the NBA. It was awkward to be called that while I was still a midshipman, but it all changed when I turned pro. My teammates always thought it was one of the best nicknames.

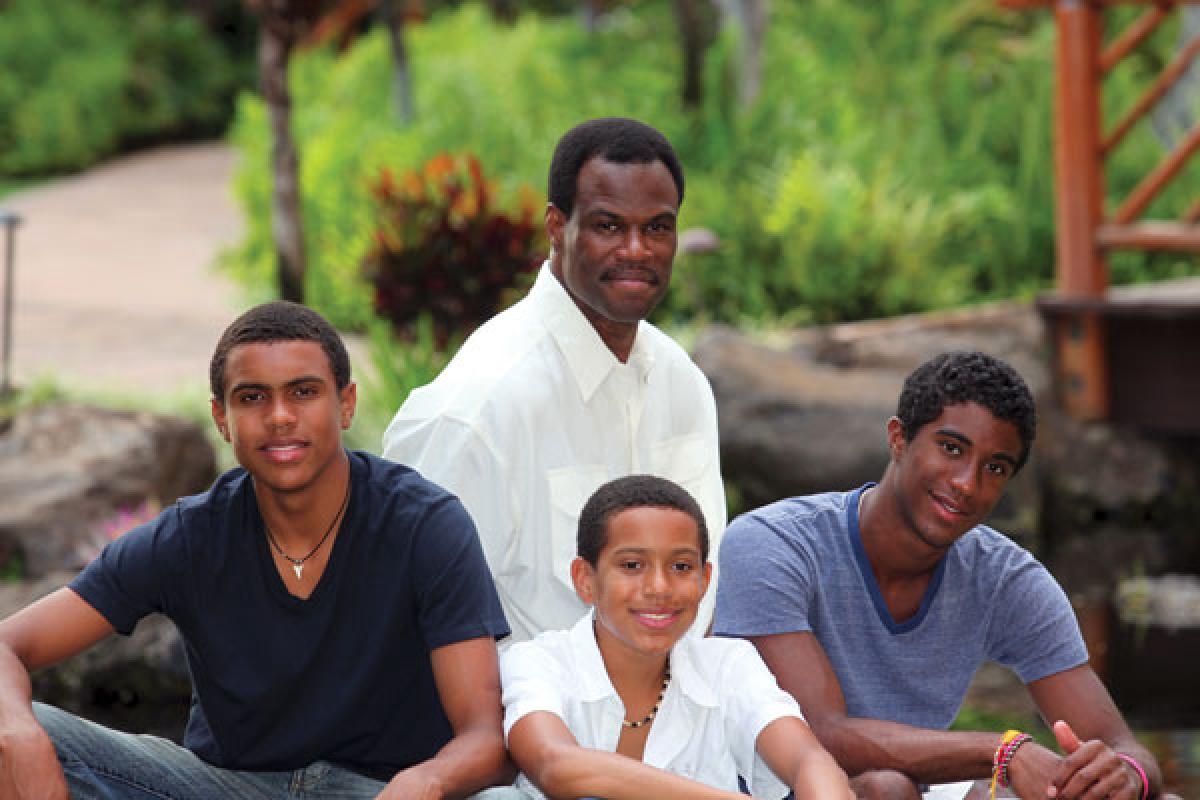

The military gave me a foundation for being a better parent, as well. No, we didn’t have close-order marching in our house, but I sometimes played drill sergeant to our three boys. Now, when I look at them, I realize they’re very well organized and on the right track. Much of that is my wife’s doing, but the Navy also played its part.

Some of the routines that became second nature to me in the Navy have stuck with me all these years. I never had to salute anyone on the Spurs, but out of habit, I did stand at attention, with my thumbs touching the seams of my basketball uniform, when the national anthem was played—a mechanism that drew wide comment from the fans.

For me, it was more than a gesture. I took those moments to think about how proud I was to be an American, and the sacrifices many African-Americans made to gain the rights I enjoy today. I never stood there fidgeting during “The Star-Spangled Banner.” I’d been trained to stand straight out of respect for the nation. I still do today.

My attachment to the Navy has stayed with me since my retirement from the Spurs. I’ve served on the Naval Academy Foundation board. And two of my sons, now in high school, are considering applying to service academies. My brother graduated from the Naval Academy in 1993, and my cousin is on course to be a 2011 graduate. We’ve got quite a family history here.

One of the most satisfying things has been keeping track of my classmates. One of my old roommates is the chief executive officer at a chain of fitness centers. Another runs a factory for a motorcycle-manufacturing firm. A third, who served as a secretary for the Joint Chiefs of Staff, invited me to visit Iraq and Afghanistan last year. Naturally, I said yes.

Would I have done as well or made it as quickly in the civilian world if I hadn’t served in the military? I really can’t say. But I do know that the experience imbued me with values and practices that have had a major impact on my life, my career, and my family, and all of it to the good. Take it from “The Admiral”—Go Navy.