The First Line of Defense

(See B. Wachendorf, pp. 22-26, November 2009 Proceedings)

Rear Admiral Brad Hicks, U.S. Navy, former Director, AEGIS Ballistic Missile Defense, Missile Defense Agency and Commander Navy Air and Missile Defense Command—Admiral Wachendorf's assessment of the complex issues arising from President Obama's decision to revamp U.S. missile-defense strategy in Europe should be required reading. He is correct that the Navy will have a much-enhanced role as the first-line of defense against a rapidly growing short- and medium-range ballistic-missile threat.

What he doesn't say, however, is telling, and additional context is needed for insight on the state of Navy BMD. Bottom line up front: the Navy is serious about BMD.

Constrained resources are perennial concerns. But initial additional funding could be forthcoming. The Fiscal Year 2010 Defense Authorization Act includes $23 million for increased buys of SM-3 missiles and another $309 million for alternative European missile-defense systems to which the Navy might have access.

Importantly, Aegis is a global enterprise. By building fleets in common with several allies, the Aegis global enterprise forms a solid foundation for the evolution of allied capabilities. This allows for a sharing of assets, responsibilities, and costs.

Operational implications are being assessed. Admiral John Harvey at Fleet Forces Command is working through myriad deployment schemes, manning scenarios, and other force-structure issues. The key question: how many BMD-ships will meet the U.S. commanders' requirements?

Ultimately, however, the emergence of a full-fledged ballistic-missile defense mission for the Navy is not that dissimilar from the strategic nuclear deterrence mission the Sea Service shouldered in the 1950s. The Navy has met such challenges previously and will do it again, even as other threats emerge in the future that require new missions and capabilities.

What is different today is that the Navy's measured BMD approach has become the linchpin in the President's strategy to craft a "stronger, smarter, and swifter" ballistic-missile defense plan to protect both America and Europe. It provides the foundation on which to evolve the capabilities that the United States and its allies need.

Afghanistan: Connecting Assumptions and Strategy

(See T. X. Hammes, W. McCallister, and J. Collins; pp. 16-20; November 2009 Proceedings)

Lieutenant Gregory G. Gagarin, U.S. Navy Reserve (Retired)—Congratulations on an excellent review of the Afghanistan situation.

I wish someone would review the same war fought by the Soviets, which eventually involved 100,000 troops. The Soviet government wanted access to the Indian Ocean for shipping use to support its agricultural and mining developments in adjacent republics.

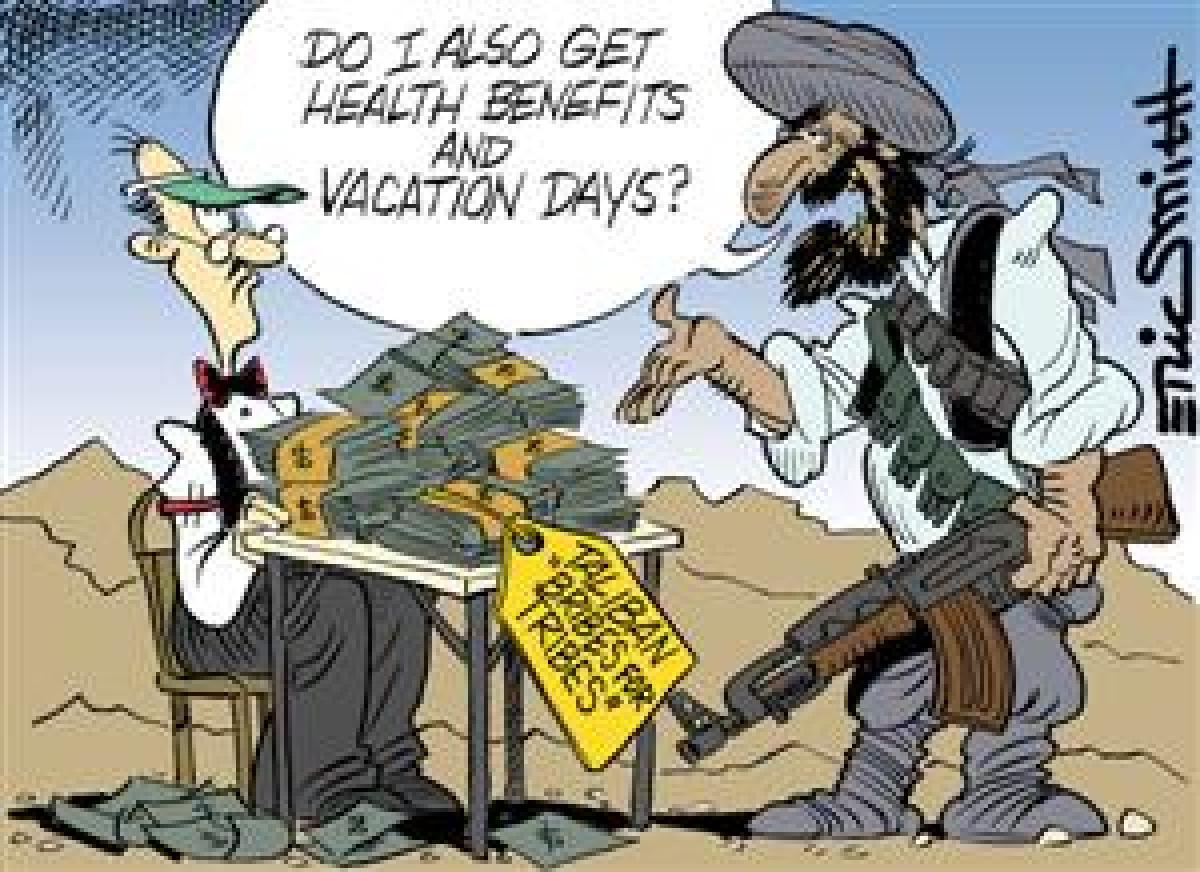

With such a large number of troops the Soviets were able to control most of the major cities, however, some tribes insisted on their independence and all were aided by the Taliban, which the U.S. government supported with arms and ammunition. As their casualties increased, the Soviets withdrew and closed the border. No trade crossed that border and as I understand it, still does not.

Shouldn't our current administration look at the history of this area, with the numerous tribes, variations of Islam, graft in trading, fiefdoms, etc.? It seems that we had a similar situation in our history in the mid-19th century with the numerous indigenous Native American tribes. It took quite a number of boots on the ground to pacify our continent, which topographically is not as severe as Afghanistan. Also, it becomes very difficult to control the illegal trade in opium grown for a considerable profit in Afghanistan. We have been trying to control this in other parts of the world with costly and questionable success.

Today, it seems obvious we should assist Pakistan in controlling their border with Afghanistan and keep the Taliban and other rogue organizations from obtaining nuclear weapons. It's bad enough that to the west of Afghanistan is Iran with its nuclear development program.

Our actions in this part of the world should be guided by a thorough knowledge of its history, morals, and developments. Pakistan and India were under British rule for many years and developed at the expense of a large number of English and Europeans who made their careers living and trading there, supported by their military. With our questionable economy, the occupation of Afghanistan for a number of years should not be considered. After World War II we occupied Japan and Germany and still have considerable interest in both countries. What interest do we have in Afghanistan?

Semper Fortis

(See J. Murphy, p. 14, November 2009 Proceedings)

Captain Larry G. DeVries, U.S. Navy Reserve (Retired)—Thank you, Senior Chief Murphy! Writing that the recent appearance of the phrase "America's Navy-A Global Force for Good" certainly "does not invoke any core motivation" is too kind. Way too kind. How about-it's lousy.

The phrase is about as inspiring as a cold oatmeal sandwich. Could we at least make it "U.S. Navy"?

We need to look no further than the Marine Corps' replacement phrases-"The Few, The Proud, The Marines" for one. Can we hire its PR firm?

The Navy's new declaration is not so much a slogan as a TV ad phrase.

Let's begin a search for a replacement starting with the words "U.S. Navy" followed by "A Global Force for Freedom," or "U.S. Navy: Ready in Peace, Strong in Defense," or "U.S. Navy: Open Oceans, Free Nations," or just "Free Oceans, Open Skies, The U.S. Navy.

As a collective we can do even better.

The Marines' verbal response of "Semper Fi" is part of their culture, who they are, not a TV ad creation. I agree that the Navy should continue to use Semper Fortis. And use it as the Marines do theirs. Slogan use starts at the top. What say you, Navy leaders?

Captain D. L. Rausch, U.S. Navy (Retired)—Huzzah, Senior Chief, Huzzah! The Navy's service identity compass continues to swing, no closer to steadying up than before. Senior Chief Murphy has succeeded in capturing that which no doubt took Madison Avenue's brightest several months and untold millions of marketing and public relations funding to produce in two words: Semper Fortis. Know who you are, never waiver, always strong.

Semper Fortis!

Combating the Managerialist Scourge

(See A. C. Wolfe, pp. 28-32, November 2009 Proceedings)

Dag K. J. E. von Lubitz, Ph.D., M.D.(Sc.)—This is a most needed article in the days when instituting an "MBA Badge" may be worth serious contemplation, and a Twitter grunt substitutes for an intelligent comment. Still, there is no reason to vilify the military unduly. After all, the business world is replete with words like "flank attack," "effect-oriented operations," and "strategy," most of which are sordidly misunderstood, and none that really illuminate the context in which they are used. If further proofs are needed, proceed to CNN's Situation Room, or even better—the very heart of it all—the Command Center, and witness sustained soft-power operations from the media frontline.

In truth, the services pilfer mercilessly the phraseology of business to warm the cockles of barely beating hearts in the uniformed chests of keyboard bashers, while their civilian counterparts pillage military terms and acronyms to add martial vigor to the dull, stilted, politically correct, and largely hypotensive prose they copiously produce. In either case, the true content and meaning need to be desperately sought, typically in vain. In both cases the reader is put firmly to sleep before the ferreting is over. The conclusion of it all is banally simple: Mahan read books, knew his history, and Tacitus was not a stranger to him. The colonel you mention suggested blogs as the source of wisdom instead. Not even very tacitly, at that. Do we need to say more?

Disorder on the Border

(See D. Danelo, pp. 44-49, October; R. Kinsella and W. H. Mattingly, pp. 6-7, November 2009 Proceedings)

Dr. W. Michael Mathes, Professor Emeritus of History, University of San Francisco; Instituto de Investigaciones Historicas, Universidad Autonoma de Baja California, Tijuana—Perhaps as a result of living and working on both sides of the border (California-Baja California) for more than 50 years, with both governments, and also being a professional historian, I find Mr. Danelo's article convoluted, bureaucratic, and evasive of the true problem of contemporary border violence.

Clearly the climate and soil of Mexico has not changed significantly in the past century, and the capacity of the country to produce opium poppies and marijuana has been constant during that period. Nevertheless, until relatively recent years (1960s to the present) the production of these crops was not economically viable because there was little market for their derivatives. However, when the use of drugs extracted from these crops became popular in the economically superior neighboring nation, the United States, a new agricultural market opened, and in many areas production shifted from corn, beans, and other subsistence crops to more lucrative poppies and marijuana. The vastness of northern Mexico made this shift relatively simple, and in many areas large plantations were developed in virtual total secrecy.

This extraordinary leap from subsistence agriculture to high-income cultivation created an economic infrastructure of production, distribution, and marketing on various socio-economic levels. As drug consumption in the United States increased, so did the production of those products demanded by it, along with expansion of their marketing. Because these operations were illegal in both the producing and consuming nations, they provided great opportunity for enormous contraband profits. These profits also permitted the ready subornation of all levels of government empowered to prevent the trade that produced them.

The increase in violence related to this illegal trade has also paralleled the increase in demand for the product, for as the profits increased the competition for a part of them by the producers, marketers, and suborned officials increased and has reached the point that there is only a limited space for these people in the trade—the remainder must be eliminated.

In my lifetime I have witnessed the changes brought about by the United States' demand for drugs along the U.S.-Mexican border, and recall readily the days when the drug trade did not exist, but rather the greatest crime problems we had in trans-border relations were related to U.S. service personnel misbehavior in Tijuana and spring break parties at Ensenada and San Felipe.

Is it too difficult for writers such as Mr. Danelo to recognize the clear parallels between current drug law enforcement and enforcement of alcohol prohibition? Is there a fundamental difference between the violence in Ciudad Juarez and Tijuana and that of Detroit and Chicago during the age of prohibition? Is the fact that a neighboring nation that can produce a product prohibited by its neighbor will do so and market it by contraband? Is there a real difference between alcohol in Canada in 1929 and drugs in Mexico in 2009? The only way to halt violence related to the drug trade (as well as numerous other aspects of crime resulting from it) short of obliteration of thousands of people, from high school peddlers to high ranking government officials, is to legalize the use of drugs, make them as available as aspirin, and remove the profit from the trade, just as the repeal of prohibition halted the violence and crime associated with it.

To be clear, I have never used any illegal substance and have no intention to do so, nor am I a closet drug addict hoping to buy my material at a cheaper price. Rather, I am a realist who would hope to see again the day that peace and tranquility reigns on the border. As I see it, this solution to the problem is so logical that the only reasons it is not instituted are extraordinary ignorance or incredible corruption, or a combination of both factors, in the governmental agencies concerned.

On another lesser point of accuracy, Mr. Danelo appears to be seeking to blame the Second Amendment for border violence. This does not work, in that contrary to his claims, AR-15 type semi-automatic rifles were for sale in the United States several decades prior to the current violence on the border and, while they can be illegally converted to full-auto fire, they are not the weapon of choice of Mexican drug traffickers. Preference is for weapons used by the Mexican armed forces such as M1 carbines, and Heckler and Koch submachine guns, which can be bought or stolen locally, readily concealed, and for which ammunition is readily available through theft. Most of the recent extensive sales of AR-15-type and other semiautomatic rifles in the United States have been due to the fear of legitimate gun owners of increased antifirearm legislation by the current administration, not illegal sales to non-citizens.

Dr. Griffin T. Murphey, DDS—Several inferences were made by Mr. Danelo regarding civilian ownership of guns in the United States and its possible connection to Mexican drug wars. First, the AR-15 has never been restricted to police and military sales. It was first sold to civilians in 1961, nearly a half-century ago.

No one knows what percentage of the Mexican drug cartels' weapons come from America, because Mexican authorities will not allow investigators full access to all of the guns they seize from the cartels. And 68 percent of those seized guns' serial numbers were never submitted to authorities for tracing.

Why? Because of the embarrassing fact that a large number of these weapons come from the Mexican army itself. Estimates of desertion from the Mexican army have been pretty well established at about 20,000 a year. At least one-in-ten (probably more) of these men is taking a weapon with him.

Importation of military hardware not available at U.S. gun shows (I hope USNI readers are well-informed enough to know that live hand grenades cannot be sold in the United States) is also well proven. A grenade recently thrown in a bar in Pharr, Texas, was of Korean manufacture and traced to a warehouse of cartel weaponry in Monterrey, Mexico. It came from Central or South American military stocks.

One official Mexican announcement was of a seizure of over 2,000 grenades. In another case, more than 500 grenades were intercepted being trucked in. Those grenades came from the Guatemalan Army.

It is not reasonable to assume that the Mexican cartels would rely on homemade conversions of U.S.-legal semiautomatic look-alike guns when they can buy the real full-auto weapon from international sources. They are having only minor difficulty shipping the drugs internationally; weapons are cheap and easily shipped. Blaming the U.S. civilian gun market for the violence is unwarranted and not supported by the available evidence.

Why is Digital Camouflage All the Rage?

(See J. W. Hulme, p. 10, October; R. Longshore, p. 84, November 2009 Proceedings)

Captain Christopher Rieber, U.S. Navy Reserve (Retired)—I am in total agreement with Mr. Hulme's comments. I would add that the Navy's blue digital pattern is undeniably great for hiding among all the blue and grey trees on ships. However, it would not be so great when operating on sandy beaches, around land vegetation, or when washed overboard into the ocean.

Commander J. C. Britain, U.S. Navy (Retired)—It is sad it has taken this long for this topic to be addressed in Proceedings or any other military-related periodical that I've read. Mr. Hulme has hit the proverbial nail on the head. The bottom line is that these digital patterns don't hide anything or anyone very effectively. Granted, evaluation of this topic area should be left to real camouflage experts who have to wear these uniforms. While I'm an old veteran Seabee and some may believe unqualified to say anything in this matter, I can still pass a color vision test which is usually the basic ability to see these patterns against slightly different backdrops—and I can see these digital patterns.

They stand out more than traditional camouflage patterns. While the Navy blue digital design may blend better with battleship gray than the old dungarees, that may also be debatable. To better blend in on board ship, grays and blacks may work better, especially during night operations.

Go back to the warriors who must wear these pajamas in combat for an expert's opinion. They have been there and done their combat tours. Consequently, they should have the best appreciation for camouflage reflecting the environment for concealment.

How the Military Supports Homeland Security

(See G. Renuart, pp. 26-31, October 2009 Proceedings)

Colonel Todd Fredricks, U.S. Army—I am a little troubled by the image of disembarked soldiers forming a perimeter around a UH-60 on page 30. It shows a NORTHCOM training exercise involving Soldiers bereft of the principle weapon of their trade in favor of pantomime.

If this is the current status of "train as you fight," then I fear what is in store for our forces in the future.

What's next, artillerymen yelling "BOOM!" when they pull a lanyard, armor training with broomsticks duct taped to the hood of HMMWVs, naval officers paddling around a pond in rowboats . . . ?

An Expeditionary Solution to Somali Piracy

(See J. Lloyd, p. 8, November 2009 Proceedings)

Remo Salta—Although one can admire Lieutenant Lloyd's zeal for wanting to strike at the heart of Somali piracy, it seems doubtful that the current administration, which already has two wars going in Iraq and Afghanistan, will want to risk starting yet another conflict in the Horn of Africa. Furthermore, a direct assault on Somali territory will only inflame tensions with radical Muslims in the area. However, there could be a simple solution to the piracy issue that not too many people are discussing these days. Why not bring back the Naval Armed Guard?

During World War II, the U.S. Navy placed personnel on armed American-flagged merchant ships. Although the program had mixed results, it provided a measure of protection to normally unarmed and defenseless merchantmen. Why not update the program for the 21st century? Place a small but highly trained unit on board American-flagged vessels sailing in dangerous waters armed with a variety of lethal weapons. Give the Naval Armed Guard on board these ships flexible rules of engagement so they can defend themselves with lethal force at the first sign of danger. Once the pirates understand that they will be fired on if they attack an American vessel, they certainly will not waste their time with those ships and seek out softer, more vulnerable targets.

The cost for placing a Naval Armed Guard on board a merchant ship could be paid for by the ship owners. This would undoubtedly be cheaper than hiring a commercial security firm, since the federal government would be supplying the services at cost and wouldn't be seeking a profit. Foreign ports would probably tolerate these ships carrying weapons, since they would be in the hands of U.S. Navy personnel rather than civilians. Since these same ports allow armed U.S. Navy vessels to visit them, why would they object to armed U.S. Naval personnel on American-flagged ships? Further, insurance rates on these ships would go down because their security would be virtually guaranteed by the Navy. Foreign-flagged ships would also want to pay to become American-flagged vessels just so they could qualify for this same protection. During the 1980s, foreign tankers voluntarily changed flags to qualify for American naval protection during the Tanker Wars in the Persian Gulf, so why wouldn't they be anxious for similar protection today?

The size of the Naval Armed Guard unit on board a specific ship would depend on the size of the merchantman. A 90,000-ton oil tanker would have different needs from a 30,000-ton container ship. U.S. Navy warships also could continue patrolling more dangerous trade routes to provide additional support.

Pirates are in the business of making easy money through ransom. They do not want to risk their lives by attacking a merchant ship with trained personnel armed with heavy weapons.