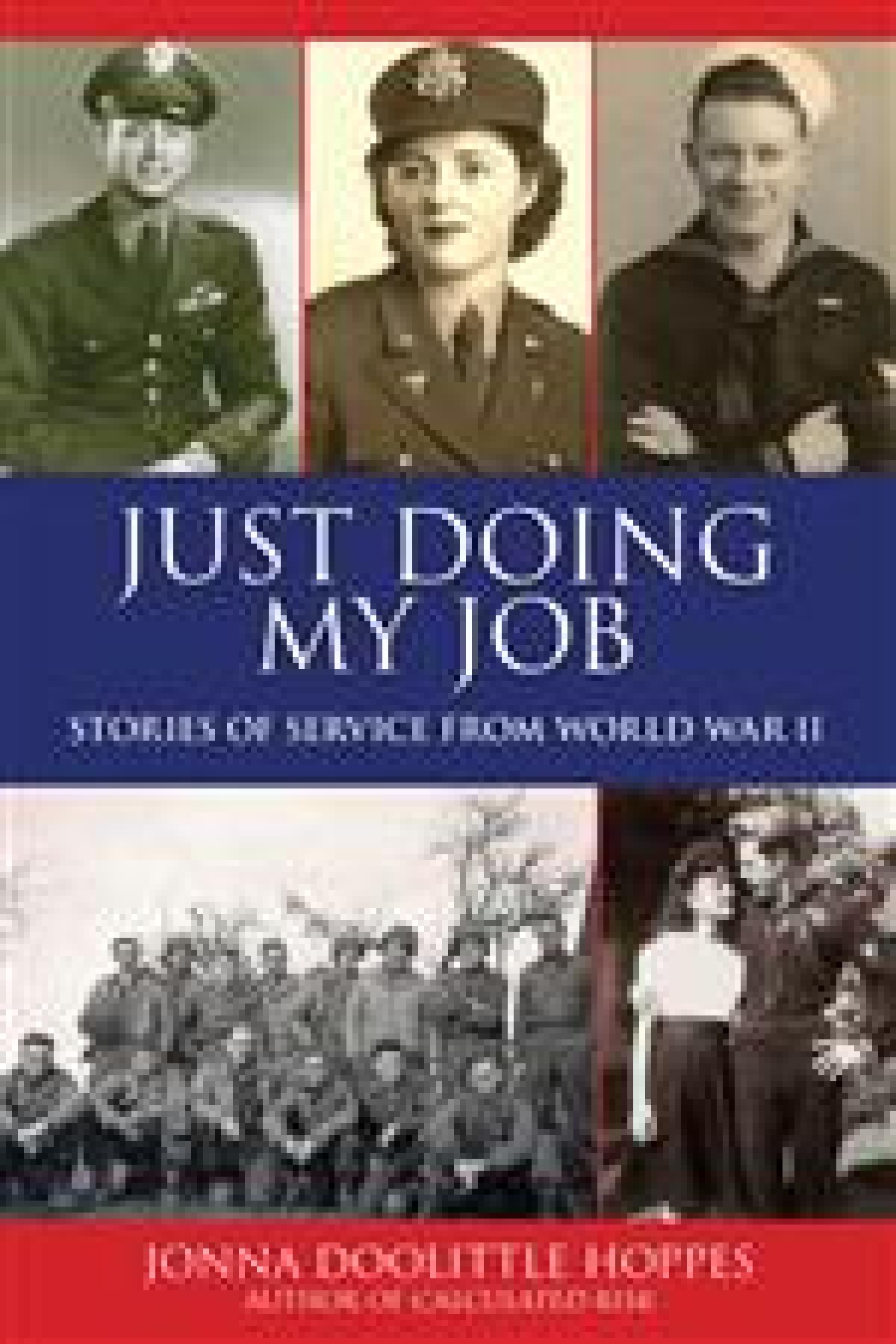

Just Doing My Job: Stories of Service from World War II

Jonna Doolittle Hoppes. Santa Monica, CA: Santa Monica Press, 2009. 344 pp. Illus. Bib. Index. $24.95.

From Soldiers and spies to factory workers and nurses, these are tales of ordinary men and women who served us well during America's costliest war. Everyone featured herein made sacrifices that are almost incomprehensible today, when even the 9/11 attacks have faded from our feeble public memory.

Bonnie Gwaltney could have been the model for "Rosie the Riveter." She worked at Douglas Aircraft, driving rivets into bomb bay doors eight hours a day, six days a week. As soon as the war ended, she noted that the "amazing opportunities women enjoyed in the workplace were pulled away as quickly as they'd been given. It was a long time before a lot of women started working again." Even so, she enjoyed traveling and supporting the war effort. "I was happy to do my part."

Dick Hamada was a Japanese-American soldier who served with the Office of Strategic Services. After training and a crash language course in Burmese, he was flown deep behind enemy lines. Initially, he doubted Kachin Ranger estimates of the number of enemy killed on a patrol. But when they "quickly pulled 20 enemy ears from their knitted pouches," he became convinced.

Jonna Hoppes surveyed the wartime experiences of 19 men and women for this book, and readers will surely appreciate her exceptional work.

Diesels for the First Stealth Weapon: Submarine Power 1902-1945

Lyle Cummins. Wilsonville, OR: Carnot Press, 2007. 756 pp. Illus. Notes. Bib. $55.

At first glance, a historian would find this to be an exceedingly abstruse book. Nevertheless, it tells a story of naval engineering that even I could comprehend. The author, Lyle Cummins, presents the information from A to Z methodically and fills the volume with illustrations of submarine diesels from their origins to the advanced stages of World War II.

Early chapters explain the work of various nations on diesel submarines. French scientists developed their first sub in 1904, but the British Admiralty's request for a reliable sub diesel in 1906 was not fulfilled for seven years. By August 1914, the German navy had "a decided advantage in the reliability and durability of the diesel engines powering them." No doubt Germany's edge paid dividends in both world wars.

The book covers U.S. submarine development dating from 1897. By 1909, the Navy had ordered six diesel-powered subs from Electric Boat Company, and Chapter 12 goes on to specify the ten diesel-powered subs designed between the world wars. Interestingly, Cummins notes that until 1940, Italy led the world in the number of commissioned subs: 115.

The author explains in great detail the introduction of locomotive diesels to our Navy. Three engine types finally reached the contract stage: one of American origin, one borrowed from German aircraft diesels, and one that turned out to be an ill-suited adaption of a German battleship engine. "By joining forces with commercial engine manufacturers the U.S. Navy got its submarine diesel and the builders their locomotive diesel."

Diesels for the First Stealth Weapons, a huge coffee-table volume, is obviously geared for the technical audience. But it is also worthwhile for the layman who strives to understand engineers.

Aboard the Farragut Class Destroyers in World War II: A History with First-Person Accounts of Enlisted Men

Leo Block. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2009. 240 pp. Illus. Gloss. Notes. Bib. Index. $39.95.

Here are compelling stories of Sailors who served on the eight Farragut-class destroyers before and during World War II. Commissioned in 1934-35 as improved four-stack destroyers, they had a length and beam of 341 by 34 feet, five 5-inch guns as main armament, and a cruising radius of 5,830 nautical miles at 14.8 knots.

The book delineates the destroyers' original complement of 162 officers and men. The CO was a lieutenant commander, and ship's company was organized in four main departments: gunnery, deck, communications, and engineering. The author also relates the facts of life in the Navy of that era, including that four-letter words were routinely used in normal conversation with other enlisted men"but not with officers."

When Pearl Harbor was attacked, Radioman 2nd Class Lloyd Gwinner of the Dewey (DD-349) related that, "At 7:55 on this Sunday morning all hell broke loose on this island outpost." Seaman 1st Class John Mooney of the Macdonough (DD-351) saw aircraft strafing them. He was scared to death, "but anxious for the opportunity to fire back."

After the Pacific typhoon of late 1944, Electrician's Mate 1st Class Frank Larson of the Aylwain (DD-355) wrote, "Lost two men. . . . Our ship rolled 73 degrees. . . . Three ships not heard from in the storm." On a lighter note, Seaman 2nd Class George Hatton of the Worden (DD-352) remembers liberty in New Caledonia. Although not a drinker, he downed a magnum of champagne. Upon leaving, "I stood up, over went the table, broken glasses. Proprietor (was) paid more than adequate for damages."

The author served in the Macdonough. Beyond his combat service, he can be proud of writing an enjoyable tale of very good men who served in good ships.

Spies for Hire: The Secret World of Intelligence Outsourcing

Tim Shorrock. New York: Simon & Schuster Paperbacks, 2009. 451 pp. Afterword. Notes. Index. $16.

According to the author, 70 percent of the U.S. intelligence budget goes to private companies working for the CIA, NSA, and other agencies. Thus the publisher sees this book as a guide to companies of the "new Intelligence-Industrial Complex," such as Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman, and Raytheon.

Spies for Hire provides a summary of that complex. It looks at Booz Allen Hamilton and the role of retired Vice Admiral J. Michael McConnell, views the history of intelligence outsourcing, examines key intelligence agencies, and surveys companies that depend largely on intelligence contracts for revenue. Finally, it deals with domestic intelligence as related to the private sector and reviews the process of congressional oversight.

Shorrock estimates that more than 80 percent of the nation's intelligence budget falls under the DOD. After 9/11, the intelligence czar created by way of legislation was given "enormous powers." As reorganization progressed, Secretary of Defense Robert Gates, for one, became "comfortable with the extent" of intelligence outsourcing.

In his conclusion, Shorrock proposes that the 9/11 attacks created a mix of patriotism, chauvinism, fear of the unknown, and war profiteering that fed into a "corporate demand for new markets and fresh sources of capital and profits." He criticizes the Bush administration for its advocacy in 2002 of "a common ideological framework for the long struggle ahead."

The book's strength lies in its exposure of fairly recent government-business collusion. But it lacks historical perspective; I found no mention of massive collaboration during the New Deal of the 1930s, or earlier use of the Pinkerton Agency for spying and union-busting in the 1890s. The Bush administration did not invent these sorts of shenanigans.