|

2008 General Prize 1st Proceedings Author of the Year |

In the war against Islamist extremists many observers have viewed al Qaeda as a collection of brilliant strategists—adaptable, flexible, culturally sensitive. In contrast, these observers often paint the United States as the opposite—stupid, slow moving, a dinosaur.1

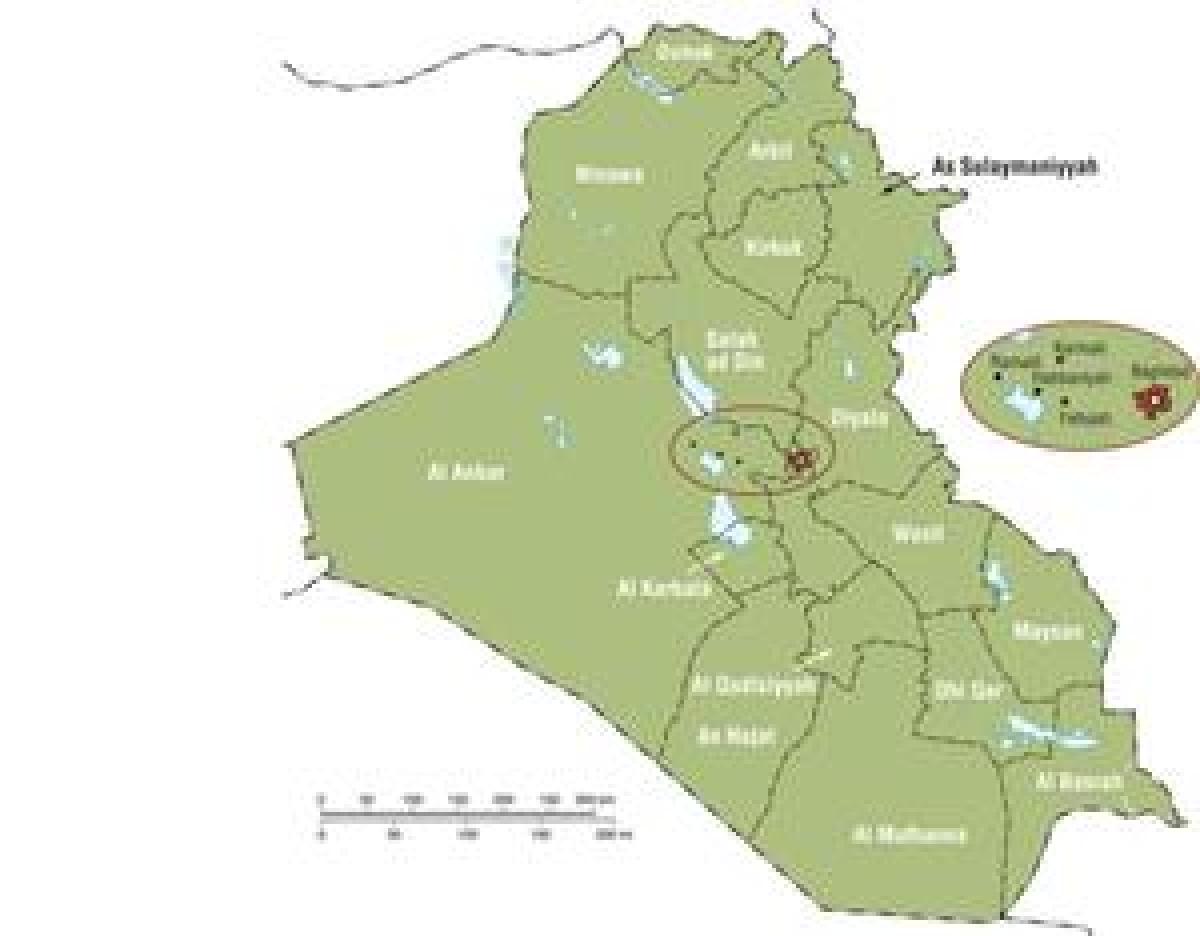

This is not the picture that has emerged, however, over the past two years in Iraq's al Anbar province (and in fact, increasingly across the rest of the country). In al Anbar, al Qaeda in Iraq (AQI) has made a series of tactical and strategic mistakes that Coalition forces were able to use to their advantage. That story has been widely reported in the press. However, the roots of these mistakes deserve more attention, because they indicate fundamental weaknesses in the organization's character and point to broader opportunities in the war.

The Iraqis are a devout Muslim people, their cities teeming with mosques. Over American objections, they wrote into their constitution that Islam is "the official religion of the state and is a basic source of legislation."2 But they are also a practical people who pride themselves on having constructed a modern state. Iraq is not Saudi Arabia, with its religious police and extreme Wahhabi sect. Conflict arose because wherever al Qaeda had influence in Iraq, it imposed a severe form of the Sharia (religious) law that went far beyond what most Iraqis would tolerate.

Some restrictions were merely annoying—forbidding the use of tobacco or requiring men to grow beards. Others were more fundamental. For example, they prevented girls from attending school. (One indicator used by the military to determine insurgent presence was the absence of schoolgirls in a municipality.) AQI imposed this on a society in which large numbers of women had participated in education at the highest levels. Its harsh criminal punishments—beheadings, amputations, beatings—are well known. However, reading about them in the abstract is one matter; seeing your school principal beheaded because he was "un-Islamic," as happened in one village, is another. AQI's lack of respect for Iraqi religious and social customs alienated the population.

Attacks on the Tribal System

Al Qaeda's global goal is to reestablish the Caliphate, a unified Islamic state where a single ruler, the Caliph, successor to Mohammed, has both civil and religious power. Such a society existed, at least in theory, during the early days of Islam.3 But a unified theistic state has no room for petty local powers—the tribal sheikhs. Indeed, al Qaeda abhors the nonreligious patron-client relationship that binds the tribes to their sheikhs. As a result, AQI routinely assassinated sheikhs and worked to undermine the tribal system by substituting its own ideological relationship for the tribal bonds.

The message to the sheikhs was clear: Die, flee into exile, relinquish power, or fight back. Some chose to fight back. Sheikh Abdul Sattar Abu Risha lost his father and three brothers to AQI assassins.4 In retaliation, he established a coalition of sheikhs in the provincial capital Ramadi ("the Anbar Awakening") in fall 2006.5 Other sheikhs followed and had immense impact on the insurgency in the province. Now this movement has not only saturated al Anbar, it has spread across the country. This alignment of sheikhs with the Coalition is particularly ironic because many observers have criticized the United States for its inability to work with tribal leaders. In fact, in contrast with AQI the United States, for all its faults, is a model of tribal diplomacy.

Faced with rising opposition from the tribes, AQI responded with terrorist attacks, which had worked before. In 2005, a group of sheikhs and government leaders in Ramadi banded together as the Anbar People's Council to establish a Sunni presence in the newly elected national government. AQI killed half of the council within a month and drove the rest out of the province. But this anti-tribal effort was a targeted assassination campaign that did not threaten the average citizen. The response in early 2007 was against the population as a whole.

In February a suicide vehicle bomber attacked a crowd outside a mosque in Habbaniyah, killing 40 people. The target may have been the outspoken imam, or it may have been a nearby police station. Whatever the objective, AQI did not apologize for the high civilian casualties. Although such mass casualty events were tragically common in Baghdad, they were unheard of in al Anbar. After all, why would insurgents attack a Sunni population that had supported, or at least tolerated, the insurgency? It appeared that terrorism, even if self-destructive, was AQI's instinctive reaction to challenges.

Attacks against the population continued, with AQI using chlorine—after experimenting with the gas through the fall and winter of 2006—for the added shock of a chemical weapon. As a weapon of mass destruction, however, chlorine was actually a poor choice. Because the gas dissipated rapidly, its effects were small compared with those of the high explosives that accompanied each incident. But gas attacks were designed for psychological effects against an entire tribe. AQI was cutting out the middle ground where most Sunnis had resided—passive support for the insurgency. It was pushing the population into either total submission or total opposition. The population chose opposition.

Inability to Adopt a Hezbollah Strategy

Hezbollah is the Iranian-supported political movement of Lebanese Shiites. Starting with only a militia in the mid-1980s, it has grown to an organization that has seats in the Lebanese government, a radio and satellite television station, and programs for social development. The social programs have been key to its success. In the areas it controls, Hezbollah runs hospitals, collects garbage, operates schools, indeed offers all the services a government would provide. After Israel's attacks in southern Lebanon in summer 2006, Hezbollah acted as the Federal Emergency Management Agency would in the United States, providing shelter to the homeless and rebuilding grants to property owners.

In Iraq, this might have been very effective. Government services were often poor, and AQI had de facto control of many municipalities. In a few areas—Karmah north of Fallujah, for example—local cells tentatively implemented such a strategy in late 2006. But to be effective AQI would have had to reallocate much of its funding from weapons and military attacks into governmental action. Ideologically it just could not do this, never diverting from its military focus. (In contrast, the Shiite militias have often become alternate governments in their neighborhoods.) As a result AQI's linkage to the population has been much weaker than it might have been.

AQI consists mostly of native Iraqis. We know this by tracking detainees, who, assuming we have captured a cross section, are something like 95 percent Iraqis. What has hurt AQI is that many of the top leaders, especially the most visible of them, are foreign. Musab al-Zarqawi, for example, who led the insurgency in its first few years, was Jordanian. Abu Ayub al-Masri, the current head of AQI, is Egyptian. The most visible global al Qaeda leaders, Osama bin Laden and Ayman al-Zawahiri, are Saudi and Egyptian respectively. The notion of foreigners causing so much death and suffering in Iraq to meet their own purposes grates on many Iraqis. Indeed, based on information from captured AQI operatives, intelligence officials now believe that AQI's Islamic State of Iraq is a front to hide its foreign roots.6

Polling in al Anbar shows the depth of feeling against foreign jihadis. Support for foreign fighters is low (under 20 percent), and the sentiment for using violence against them is strong (over 70 percent). In contrast, the local armed resistance had wide support. (The Coalition does not escape this antagonism against foreigners. Its poll numbers are as low as those of the foreign fighters.)7

Inept Expansion Outside Iraq

In 2005 bin Laden directed AQI to expand its attacks outside Iraq. One result was the 9 November suicide bombing against hotels in Amman, Jordan, an attack that seems to have been launched from al Anbar. More than 100 people were injured, and 60 were killed. Most infamously, a wedding reception was attacked, resulting in the deaths of the fathers of the bride and groom. Few Westerners were injured, the victims being almost entirely Jordanian and Palestinian.

Although al Qaeda characterized these bombings as attacks on "centers for launching war on Islam," thousands of Jordanians unexpectedly marched in protest, chanting, "Burn in hell, Abu Musab al-Zarqawi!"8 Al Qaeda is not stupid and stopped such attacks outside Iraq. But the damage had been done. What American diplomacy and outreach had been unable to do, al Qaeda did for us, and that was to turn the Jordanian population decisively against Islamic extremism.9

This inept expansion may have blunted al Qaeda's most powerful weapon against the West—the infiltration of hardened and radicalized jihadis to conduct terrorist missions. Since the beginning of the insurgency, Western observers have expected, and feared, that Iraq would become a training ground and launching base for attacks against the United States and Europe. The model was Afghanistan during the anti-Soviet insurgency. Foreign insurgents received training and combat experience there, and after the war, like bin Laden himself, returned home to cause political and security problems. Indeed, a recent National Intelligence Estimate warns that "al Qaeda will probably seek to leverage the contacts and capabilities of al Qaeda in Iraq."10 But it has not happened yet, and for a good reason.

Every month about 60 foreign jihadis infiltrate Iraq, but for them it is a one-way ticket. Most die as suicide bombers. About 80 percent of suicide bombers in Iraq are foreigners, the Iraqis being reluctant to sacrifice themselves in that way. The rest die in engagements with Coalition or Iraqi forces. It used to be said in al Anbar that the foreign jihadis were the ones who changed ammo magazines in a firefight. In contrast, the Iraqi insurgents would fire one magazine and then withdraw. This made the foreigners very dangerous, but it eventually doomed them. Thus, the feared pool of terrorists has not materialized.11

The Coalition Responds

It is now commonplace to hear how unprepared the U.S. military was for the occupation of Iraq. Despite a decade of citing "full-spectrum capabilities," neither the Army nor the Marine Corps was ready to conduct an effective counterinsurgency campaign. What they were able to do, however, was to improvise and adapt, so that when opportunities presented themselves, the Coalition was able to take advantage of them.

- Engagement with the tribes. Prior to Operation Iraqi Freedom, few military officers outside the Special Forces community thought much about civilian power structures. But when faced with conducting an extended occupation of a tribal society, Marines and Soldiers responded by making contacts with the local communities. Despite allegations to the contrary, U.S. commanders engaged the tribes from the beginning of the conflict.12 In al Anbar these efforts bore little fruit initially, because the sheikhs were not ready to respond. They were angry about the Sunni loss of power and hated being occupied by a foreign power. With AQI's mounting errors, however, the sheikhs' thinking changed, and when it did, the U.S. forces had a relationship to build on.

- Police capabilities ready when the tribes were. AQI fears the local police (and now the "Concerned Local Citizens" groups) far more than the Iraqi Army, because police know the community—who belongs, who does not, who can be trusted, where to get information. Being entirely Sunni, al Anbar lacked the sectarian divides that hurt police forces elsewhere. In conjunction with the embryonic Iraqi government, the United States re-established a police force with equipment, training, and facilities, but through the spring of 2006 recruiting was slow. Only a few thousand joined. When the sheikhs stood up, however, a mechanism was in place to provide immediate local security. Thousands of tribesmen joined the police and were formally trained at police academies so they would not act as undisciplined militias. They then saturated what had once been insurgent neighborhoods. Today, more than 20,000 trained police are in al Anbar, and they have smothered the insurgency.

- United States adopts a Hezbollah strategy. Civil affairs has always been a military capability, but prior to the conflict in Iraq it had been distinctly secondary to warfighting. In Iraq, civil affairs became central. Along with efforts by the Corps of Engineers, the Agency for International Development, and the State Department (through Provincial Reconstruction Teams), civil affairs teams worked to provide the kind of infrastructure services and local governance that had collapsed along with the Saddam Hussein government.

- AQI atrocities widely publicized. Information operations generated great interest during the 1990s, and their proponents foresaw decisive results. However, implementation was much more difficult than expected, as local attitudes proved resistant to outside manipulation. Nevertheless, the basic tools—radio, leaflets, and magazines—were in place so that when AQI committed an atrocity, the Coalition could make sure that the community knew about it. This kept the sheikhs informed as they considered their options and later served to explain the sheikhs' actions to the community and to rally the population to anti-AQI activities.

The confluence of AQI errors, tribal reaction, and U.S. adaptation produced dramatic results: Incidents in the province dropped by 90 percent. With the improvement of the security situation all the key counterinsurgency metrics began pointing decisively up.

Al Qaeda Still a Threat

Al Qaeda is well aware of these weaknesses in its strategies, and people who follow their Web sites report much hand wringing. Osama bin Laden himself has conceded that mistakes were made and exhorts his followers to greater efforts. Outsiders might observe that AQI should alter its behavior to gain adherents. But it can't. The Sharia, the yearning for the Caliphate, the hatred of its enemies, and the global—and hence foreign—leadership define al Qaeda as a movement.

Despite these weaknesses and country-wide reverses, al Qaeda remains a ruthless and dangerous foe. It retains strength inside Iraq and still has broad global appeal. Nevertheless, it has clear and substantial vulnerabilities that the United States has exploited in Iraq and may be able to exploit elsewhere. Past success in capitalizing on these weaknesses should also give the West some encouragement for the long war against Islamic extremism. Just as the Cold War was fundamentally a long-term but winnable ideological struggle, so, too, is this one.

1. See The Nation, on line edition, 11 September 2006.

2. See Constitution of Iraq, 2005, Article 1, section 1, which has many religious references but does also guarantee religious freedom.

3. Technically the Caliphate ended in 1924 when Kemal Ataturk, ruler of Turkey, abolished the Ottoman Caliphate as part of his modernization campaign. However, jihadis hark back to the period of the first four "righteous" Caliphs (633-661) as the Golden Age. For a full explanation, see Mary Habeck, Knowing the Enemy: Jihadist Ideology and the War on Terror (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2006).

4. Because Arabic names do not render easily into English, many versions of his name are used—for example, Abdul Sattar al-Rishawi or Abdul Sattar Buzaigh al-Rishawi. Sattar was assassinated in September 2007 but his coalition of sheikhs continued.

5. This coalition called itself the al Anbar Awakening ("Sahawa al-Anbar" in Arabic). Recently it has started calling itself "Iraq Awakening," indicating broader ambitions.

6. "Terror Leader Exposes Network," Washington Times, 19 July 2007, p. 1; "Al-Qaeda in Iraq Duped into Following Foreigners, Captured Operative Says," American Forces Press Service, 18 July 2007. This information came from interrogation of Khalid Abdul Fatah Daud Mahmud al-Mashadani, a senior AQI operative captured in early July 2007. Al-Mashadani said that the notional head of the Islamic State of Iraq, Umar al-Baghdadi, did not in fact exist and was manufactured to hide AQI's foreign leadership.

7. Al-Anbar Trend Survey April 2007, Lincoln Group, Unclassified, and Final Survey Report Al Anbar IO Survey 11, Sept./Oct. 2006, Lincoln Group, Unclassified, both produced for Multi National Force-West (MNF-W).

8. See for example: "Furious Jordanians Take To Street", CNN Report, 11 November 2005.

9. A similar phenomenon appears to be happening in Pakistan. There, the recent wave of suicide bombers has greatly reduced al Qaeda's popular support, from 33 percent in August 2007 to 18 percent in February 2008. See "Bin Laden Backing Plummets," The Washington Times, 11 February 2008, p. 14.

10. See National Intelligence Estimate: The Terrorist Threat to the US Homeland, July 2007.

11. In February 2008 the Director of National Intelligence, Michael McConnell, testified that fewer than 100 al Qaeda militants had left Iraq to establish cells elsewhere. See "Intelligence Chief Cites Qaeda Threat to US," New York Times, 6 February 2008).

12. See for example, John F. Kelly, "Tikrit, South to Babylon", Marine Corps Gazette, March 2004, pp. 37-42, for a description of early tribal engagement by the military.