On the morning of 24 October 1944, in a pair of Hellcat fighters, Commander David McCampbell and his wingman, Ensign Roy Rushing, scrambled from the flight deck of the USS Essex (CV-9) to repel a formation of 40 inbound Japanese aircraft. Rushing had a full load of fuel, but McCampbell had been forced to take off before his tanks were full. Undetected by the enemy, the two lone Hellcat pilots were able to position themselves above and behind the Japanese. As one of the enemy fighters began lagging behind the formation, McCampbell pounced like the lion who focuses its attack on the straggler from the herd. Diving down, he waited until he could see the bright red "meatball" insignia contrasting sharply with the olive-drab fuselage of the Japanese fighter. Then, easing the stick back to reduce the angle of his dive and centering his target in the gunsight, McCampbell squeezed the trigger. The Hellcat shuddered noticeably as it coughed out a spray of deadly .50-caliber incendiary rounds. Tracers painted a path to the target, and the plane exploded, then plummeted from the sky. Rushing and McCampbell each downed another fighter before the Japanese even realized they were under attack.

As McCampbell headed straight for the next nearest fighter, he opened fire, but this time he faced an adversary rather than a victim. Glaring tracers flashed past him as the enemy fought back. At a relative speed of nearly 400 knots, the two opponents passed by one another in an eye-blink flash. Neither dropped from the sky.

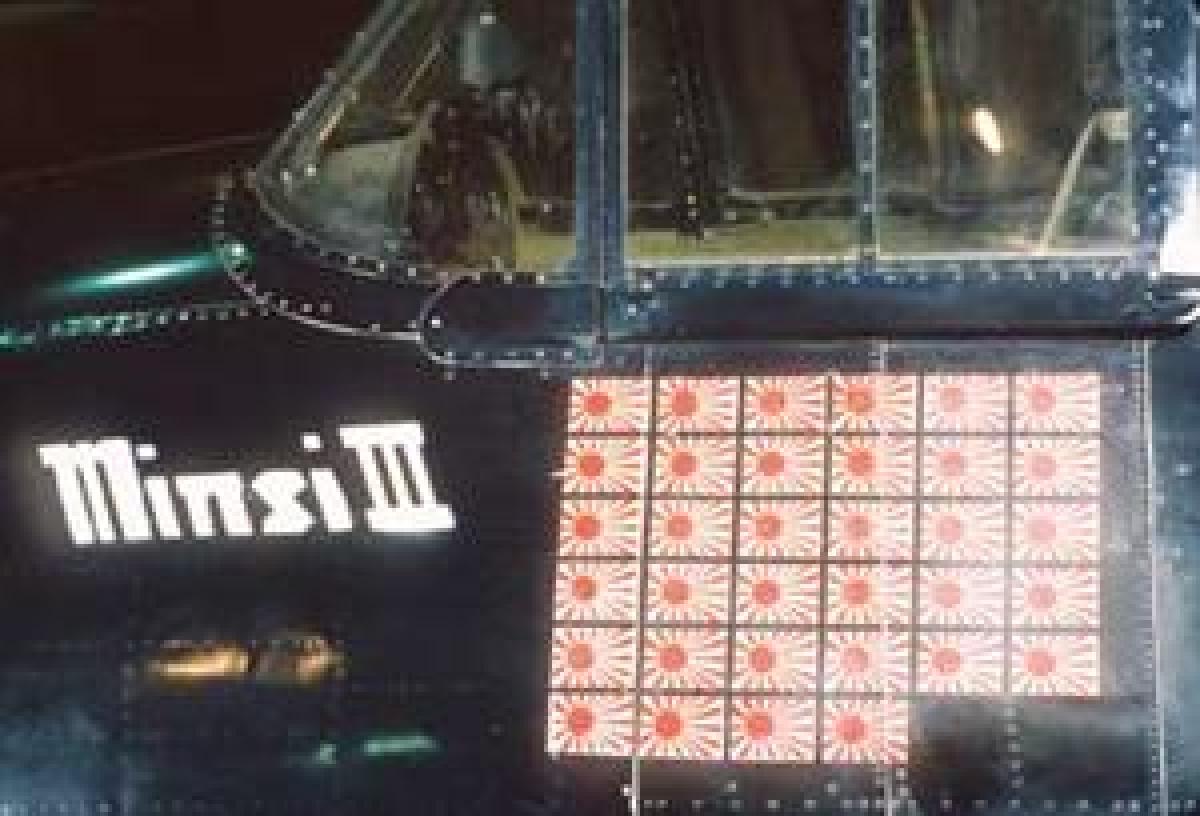

By now, more Americans had joined the fray, and a wild mêlée ensued. Unfortunately, McCampbell's fuel was running out and he noted a number of ugly black holes in his wings where enemy rounds had scored hits. But McCampbell's aircraft was not adorned with 21 Japanese flags because he was in the habit of heading for home when the going got tough.

Swooping back into the chaos, he soon downed another enemy aircraft. Then another. And another. And yet another. And. . .Eventually, both McCampbell and Rushing were out of ammunition, and McCampbell's fuel was now dangerously low, so the two at last turned back toward the Essex.

As they approached the U.S. formation, one of the American ships in the task group mistook the two Hellcats for Japanese aircraft and opened fire. Five-inch rounds began detonating nearby, and McCampbell and Rushing descended to just above the wave-tops, jinking violently back and forth in fuel-consuming maneuvers to avoid being hit by the "friendly" fire. Then several American fighters joined in, diving down on the two lone Hellcats, who by now had nowhere to go but into the sea. At the last possible moment, the American fighters realized their mistake and broke off the attack.

With his fuel gauge hard left, McCampbell finally reached the Essex, but found her flight deck fouled by launching aircraft. Fortunately, the two men were able to land on the USS Langley (CVL-27). And it was none too soon, as McCampbell's engine coughed and died before he had a chance to shut it down.

But it had been a fruitful mission in which history had been made. McCampbell had confirmed kills on an incredible nine aircraft (with two probable, but unconfirmed, additional kills), and Rushing had splashed another six—a record that has never been equaled.

Commander David McCampbell

By Lieutenant Commander Tom Cutler, U.S. Navy (Retired)