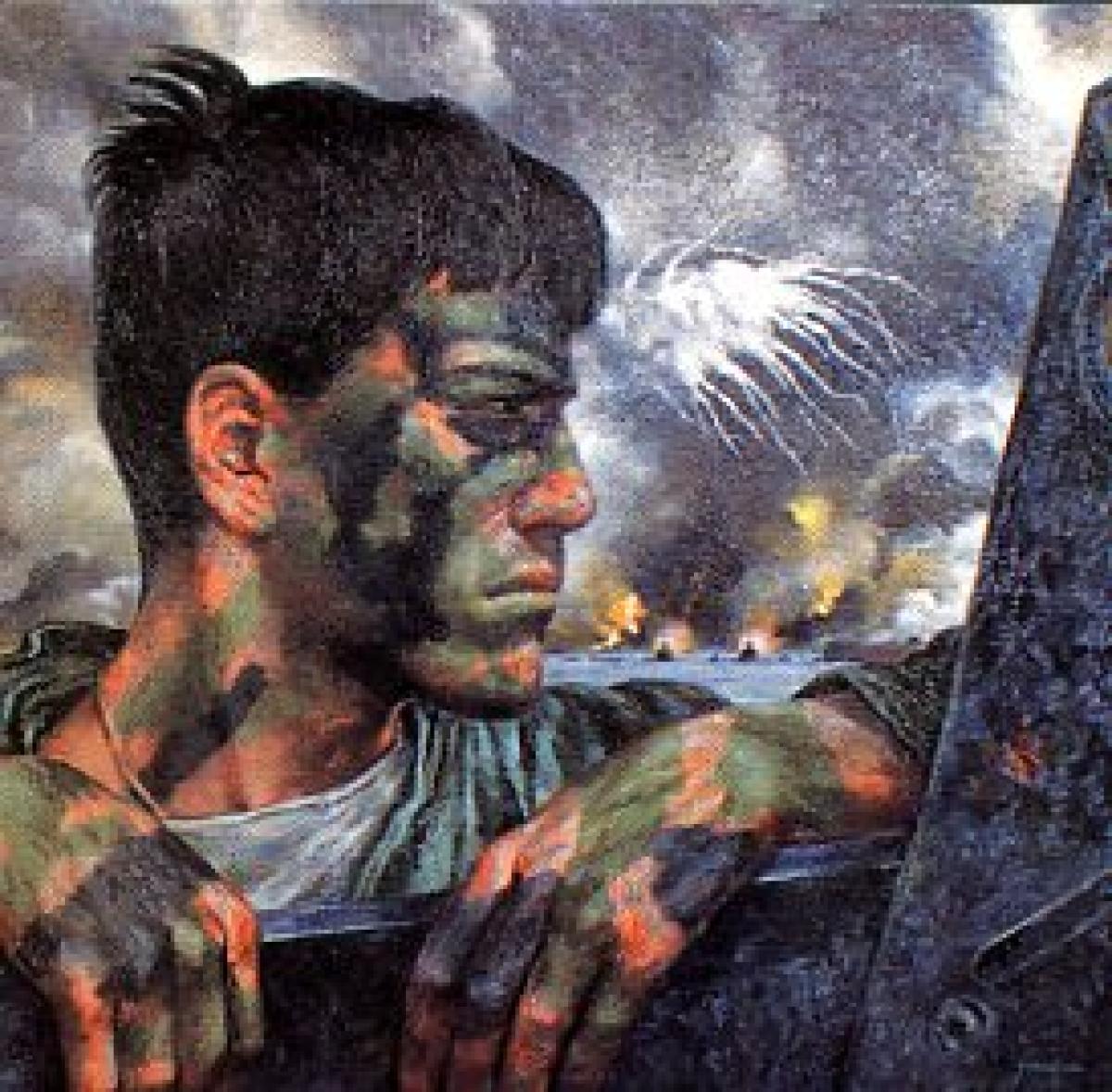

One of the most controversial operations of World War II in the Pacific was the 1944 invasion of Peleliu. A military historian has analyzed the circumstances and the personalities involved, trying to answer a question that has nagged veterans such as the one pictured here for more than 54 years.

Few World War II veterans of the 1st Marine Division and the Army's 81st Division ever made sense of the awful sacrifices it cost to wrest Peleliu from a stubborn foe entrenched in the badlands of the Umurbrogol, a moonscape known as "Bloody Nose Ridge." Many survivors consider Peleliu's worst legacy to be that their fleet commander, Admiral William F. Halsey, Jr., had recommended canceling the landing at the last moment—only to have the suggestion rejected by Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, commanding the Pacific Fleet and the Pacific Ocean Areas (CinCPac/CinCPOA). Nimitz has since been excoriated for this decision. "CinCPac here made one of his rare mistakes," observed Samuel Eliot Morison in 1963. Three decades later, naval historian Nathan Miller described the event as "Nimitz's major mistake of the war."

Yet Nimitz made few rash decisions in 44 months as CinCPac/CinCPOA. He picked discerning staff officers, sought the advice of tactical commanders, and hearkened to his outspoken boss, Admiral Ernest J. King, Commander-in-Chief, U.S. Fleet (CominCh), and Chief of Naval Operations. How did Nimitz reach his decision about Peleliu, and upon what information did he base his judgment?

The 72-hour period during 12 to 15 September 1944, essentially the three days leading to D-Day at Peleliu, was a time of significant westward movement by U.S. forces. As one attack force converged on Peleliu and Angaur in the southern Palaus, another embarked in Hawaii for Yap and Ulithi in the Western Carolines, the second phase of Operation Stalemate, and yet a third amphibious unit advanced on Morotai in the Moluccas. Complex as they were, each operation had the principal objective of paving the way for even larger campaigns soon to follow—MacArthur's return to the Philippines, Nimitz's conquest of Formosa or (as some planners were beginning to suggest) Iwo Jima and Okinawa.

The key players were scattered widely. King and the other Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) were engaged in the Octagon Conference in Quebec with their British counterparts and Sir Winston Churchill. Nimitz held forth in his headquarters in Pearl Harbor. General Douglas MacArthur, counterpart to Nimitz as commander-in-chief of the Southwest Pacific Area (CinCSowesPac), sailed with the Morotai invasion force. And Halsey, less than three weeks in command of his newly designated Third Fleet, strode the flag bridge of the USS New Jersey (BB-62) in the throes of indecision.

Halsey had just arrived in the Philippine Sea, linking up with Vice Admiral Marc A. Mitscher, commanding the fleet's principal striking element, Task Force 38. Mitscher reported the results of air raids conducted by his fast carriers throughout Mindanao, scheduled to be MacArthur's first major objective in the islands in late fall, following Peleliu and Morotai. Mitscher told Halsey the lack of Japanese opposition had rendered the mission useless.

Mitscher's report surprised Halsey. He had assembled the Third Fleet in the Philippine Sea to cover Nimitz's two Stalemate task forces and begin setting the stage for MacArthur's Mindanao landing. Halsey expected a hard fight for air supremacy throughout the Philippines. Perhaps Mindanao had been a fluke. But Mitscher then launched 2,400 sorties against the central Philippines during 12 to 13 September with similar results—scant opposition and little evidence of front-line enemy air units.

At that point, Halsey's forces extracted a downed U.S. aviator from Leyte. In an interview with Halsey, the pilot said that the natives who had rescued him told him that the Japanese were not in Leyte in force. The island was ripe for invasion.

Halsey knew the 11th hour had come for Operation Stalemate. He also knew the complex campaign had already gathered its own momentum under Vice Admiral Theodore S. Wilkinson, Commanding Task Force 31, with its joint-service III Amphibious Corps destined to hit Peleliu on 15 September and its U.S. Army XXIV Corps slated to seize Yap and Ulithi on 3 October.

Halsey sought the advice of his chief of staff, Rear Admiral Robert B. ("Mick") Carney, and his newly appointed chief of staff for fleet administration, Commander Harold E. Stassen, the former three-term governor of Minnesota. As Stassen recalled the debate: "Halsey was sobered by the significance of what he was recommending. We had our marching orders, now we were asking the Joint Chiefs to change their script."

In June, Halsey had gone out on a limb by expressing his personal belief to the JCS that any amphibious campaign against Peleliu, Angaur, Babelthaup, or Yap (the Stalemate objectives) would be prohibitively costly, contribute little to MacArthur's return to the Philippines, and constitute an unnecessary detour on the road to Tokyo. Neither Nimitz nor King supported Halsey's view, and Operation Stalemate kept its destiny. Halsey knew Nimitz and King would suspect him of trying to reopen that issue at this late date.

"The clincher was the report of the rescued aviator," said Stassen. Halsey concluded that if Leyte was indeed ripe for invasion, then the Mindanao campaign was superfluous and therefore the pending seizure of the heavily defended Palaus no longer essential. Halsey then authorized Stassen to release two Top Secret messages.

Halsey's first message (COM3RDFLT 130230Sep44) went to Nimitz, MacArthur, and King. "Downed carrier pilot rescued from Leyte informed by natives no Nips on Leyte," Halsey reported, adding "Planes report no military installations except bare strips on Leyte."

Halsey used the first message to set the stage for the real bombshell (COM3RDFLT 130300) to Nimitz, King, and MacArthur. "Am firmly convinced Palau not now needed to support occupation of Philippines," wrote Halsey. "Western Carolines not essential to our operations (except Ulithi) .... Believe that Leyte fleet base can be seized immediately and cheaply without any intermediate operations. ... Suggest that Task Force 31 could be made available by CinCSowesPac if Stalemate II canceled."

This was heady stuff. Cancel Stalemate entirely, except the seizure of lightly defended Ulithi Atoll, scratch Mindanao, move the Leyte campaign to front burner—in effect, accelerating the entire Pacific campaign plan by months—and offer Wilkinson's III Amphibious Force (a Nimitz asset) to MacArthur for the Leyte job. Interestingly, Halsey never used his oft-quoted prophesy about Peleliu—"I fear another Tarawa"—in any of these pre-D-Day messages. Those were postwar words.

The date was still 12 September in Pearl Harbor when Nimitz received Halsey's messages. His reaction remains lost to history. His flag lieutenant, H. Arthur ("Hal") Lamar, recalled no flashes of stormy impatience, as Nimitz rousted his key advisors for a council of war. He knew time was short.

As commander of a million-man force, Nimitz proved to be an exceptional judge of the character and potential of his principal lieutenants. By picking such resourceful tactical commanders as Raymond Spruance, Halsey, Mitscher, Kelly Turner, Holland Smith, and Roy Geiger, Nimitz could afford to keep his eye on the big picture. In time he became an accomplished strategist. A partial insomniac, he converted his sleepless hours after 0300 into careful study of his charts of the Western Pacific.

Halsey's message required Nimitz to face two chief issues. Operation Stalemate took top priority because of its immediacy, but the bigger strategic issue was the accelerated invasion schedule for the Philippines. Nimitz had the authority to decide the fate of Stalemate—re-shuffling the Philippines sequence would require MacArthur's considered input and a JCS resolution.

Stalemate, especially the first-phase assault on Peleliu, needed an immediate resolution. It was not simply a matter of turning around the troop transports. Rear Admiral George H. Fort, commanding the Western Attack Force, already had committed shore-bombardment ships, dive bombers, minesweepers, and underwater demolition teams to the battle. Frogmen were in the shallows, shoreward of the reef, attaching explosives to moored mines and antiboat obstacles.

Nimitz rendered his decision to Halsey in three terse sentences (CINCPAC 130747Sep44 to COM3RDFLT, info King and MacArthur): "Carry out first phase of Stalemate as planned. Am considering eliminating occupation of Yap.... In any event will occupy Ulithi as planned...." Minutes later Nimitz sent a message to MacArthur (CINCPOA 130813 to CINCSWPA, info King and Halsey) advising that "if occupation of Yap is eliminated, 24th Corps, including 7th, 77th, and 96th Divisions . . . would be potentially available to exploit favorable developments in the Philippines. Your view on this and COM3RDFLT's 130300 requested."

With MacArthur en route to Morotai under radio silence, his chief of staff, General Richard K. Sutherland, quickly mustered his advisors in Hollandia, New Guinea, eager to project the views of the Southwest Pacific Area into the debate. Meanwhile, watch officers in the Pentagon forwarded each of the messages from Halsey and Nimitz to Quebec for delivery to King. Halsey had foreseen the flurry of top-level activity. His recommendations, he admitted later, "in addition to being none of my business, would upset a great many apple carts, possibly all the way up to Mr. Roosevelt and Mr. Churchill."11

The Joint Chiefs made no specific mention of Peleliu, but picked up quickly on Halsey's other proposal to cancel Yap and use those sizable forces to augment an accelerated invasion of Leyte. "Highly to be desired," they signaled to MacArthur on 13 September. Sutherland soon responded in MacArthur's name, first dispensing with Halsey's intelligence coup—"report by rescued carrier pilot incorrect according to mass of current evidence"—but concurring with the cancellation of Yap and Mindanao. Sutherland's rambling discourse in his name was likely too much for MacArthur, who broke radio silence one day later with a cryptic message in his emphatic style: "I am prepared to move immediately to execution of K2 [Leyte] with target date October 20th."

MacArthur's message was dramatic enough for aides to break the Joint Chiefs away from a formal dinner in Quebec the night of the 14th. In 90 minutes the two admirals and two generals agreed. Their enabling message to Nimitz and MacArthur, "Octagon 31-A," compressed the Pacific War strategy by two full months—a nice evening's work.

But Peleliu remained on the boards. The JCS may have purged Operation Stalemate of its mission to Yap, but the requirement for forcible seizure of the southern Palaus did not change. Indeed, at the same time the Joint Chiefs disrupted their dinner in Quebec, the assault elements of the 1st Marine Division were just crossing the line of departure at Peleliu, discovering to their horror that an abbreviated naval gunfire bombardment hardly had dented Japan's vicious matrix of anti-invasion weaponry.

So, what did Nimitz know about Peleliu? Why cancel a two-division assault on Yap and retain a similar-sized assault on Peleliu and Angaur? One set of clues may exist in a pair of messages released by Nimitz on 13 September during the lull between his early-morning signals to Halsey and MacArthur and his receipt of the first JCS response. Nimitz took the time to share with Halsey a bit more of the theater commander's perspective on the Palaus. The purpose for seizing Peleliu, Angaur, and Ulithi, he wrote, "include[s] not only support of occupation of Philippines, but also completion of neutralization of highway and support of advances into Formosa-Luzon-China coast area and operations against objectives to northward." Nimitz then sent a personal message to King, stating "The occupation of Palau and Ulithi are of course essential and it would not be feasible to reorientate the plans for the employment of the Palau attack and occupation forces as rapidly as Halsey's 130230 appears to visualize."

Nimitz added a zinger. If MacArthur hesitated to employ the proffered 24th Corps, "it may be possible to take Iwo Jima in mid-October using the Yap force." The Eastern Task Force then loading in Hawaii was huge—more than 100 amphibious ships, escorted by 21 destroyers, a 50,000-man landing force. Coupled with the fast carriers of Mitscher's Task Force 38, "the Yap Force" may well have succeeded in taking Iwo Jima four months ahead of schedule. But King did not bite, MacArthur quickly claimed the Yap Force, and Iwo Jima would have to wait its bloody turn.

Historians often have assumed that Nimitz retained Peleliu because of his personal assurance to MacArthur, in the presence of President Franklin D. Roosevelt at the Pearl Harbor "Summit" of 26 July 1944, that he would seize the island on 15 September to coincide with MacArthur's capture of Morotai, thus facilitating the westward passage of the Philippines invasion force. Yet Operation Stalemate had taken its final wrinkle, including reaffirmation of DDay, weeks earlier. That Nimitz intended to land on Peleliu on 15 September should have been nothing new either to MacArthur or Roosevelt at Pearl.

Nimitz's personal reasons for deciding to retain the Peleliu landing can be deduced only by hindsight. We can safely rule out, it seems, factors of self-doubt, resentment toward Halsey's initiative, or callousness toward the likely costs. Nimitz's style of hands-off leadership would encourage exactly the kind of initiative that Halsey had just demonstrated. Nor did any evidence surface of callousness in Nimitz's character, according to those who knew him intimately. As Hal Lamar, his personal aide throughout the war, stated afterward: "This used to hurt him very much, but I've heard him say to me, `This is going to cost me ten thousand people.' . . . He hated to know that he was issuing an order that would mean the loss of so many lives." Similarly, in one of his few surviving letters to his wife, Nimitz wrote from Iwo Jima of the "spite mail" he received from grieving parents, admitting "I am just as distressed as can be over the casualties but don't see how I could have reduced them." He was waging a grim war. Indeed, Nimitz's amphibious drive across the central Pacific ultimately incurred 100,000 American casualties.

Analysis of Nimitz's Peleliu decision within the context of his total performance in the protracted war suggests four likely contributing factors: a political sensitivity to fragile "Home Front" morale, loyalty to King, his own sense of strategic priorities, and overconfidence

Nimitz probably sensed that Halsey's message had come too late for Peleliu. Japanese gunners on Peleliu that day had shot U.S. Navy carrier aircraft out of the sky. Their swimmers this night were boldly laying new mines in the boat lanes cleared earlier by underwater demolition teams. Nimitz knew if he broke contact at this point, he would be handing the Emperor of Japan a priceless propaganda gem and creating a political disaster for President Roosevelt.

Among these four factors, Nimitz's close relationship with King likely proved most crucial. They had not always seen eye-to-eye on the necessity of invading the Palaus, but a sharp memo from King on 8 February 1944 (after the initial success of the Marshalls campaign) spelled out for Nimitz his objectives for the remainder of the year. "Central Pacific general objective is Luzon," said King, "[which] requires clearing Japs out of Carolines, Marianas, Pelews [sic]—and holding them." This strategy, King argued, would cut the Japanese lines of communication to the Dutch East Indies and protect the flank of MacArthur's forces advancing to Mindanao.

A month later, Nimitz went to Washington to provide this same rationale to the Joint Chiefs, the Joint Staff Planners, and President Roosevelt. Nimitz's memorandum, "Sequence and Timing of Operations, Central Pacific Campaign," contained King's earlier words, then added Nimitz's own views on the importance of Ulithi as a fleet anchorage in the westward drive, which would require the neutralization of nearby Yap and thus the seizure of the Palaus (Peleliu or Babelthaup). Nimitz suggested a November landing. The Joint Staff planners upped the ante, recommending a September date and declaring the capture of Palau to be "essential to an invasion of the Philippines and an assault on Formosa" as a main naval base, citing the Palaus' airfields, sheltered anchorages, staging areas, and water depth sufficient for a floating drydock to be brought forward from Espiritu Santo.

The Joint Chiefs then issued strategic guidance to MacArthur and Nimitz concerning the forthcoming Pacific campaigns. They set a target date of 15 September for the Palaus and specified the objective: "to extend the control of the eastern approaches to the Philippines and Formosa, and to establish a fleet and air base and forward staging area for the support of operations against Mindanao, Formosa, and China."

Peleliu could have been had for the asking in March. A light force of Imperial Navy antiaircraft gunners comprised the island's principal defense. But Nimitz's bold success in the Marshalls—leapfrogging first to Kwajalein, then all the way west to Eniwetok—caused consternation among Imperial General Headquarters. For the first time, the Japanese began pulling units from their elite Kwantung Army defending Manchuria against the Soviet Far Eastern Army to face the U.S. threat in the Central Pacific. On 10 February 1944, the 14th Division received orders to leave its positions along the Nonni River above Tsitsihar. By June the buildup of Imperial Army forces in the Palaus caused Nimitz enough concern to abandon Babelthaup and concentrate instead on the smaller islands of Peleliu, Angaur, Yap, and Ulithi. King would not take kindly, Nimitz sensed, to further tinkering with Stalemate's objectives. In short, Nimitz and King had hammered out their plans for the Palaus campaign over an intense seven months.

On a personal level, Nimitz likely determined that he had a clearer concept of the strategic situation in the Pacific than did Halsey. Halsey's galvanic messages provided good rationale for accelerating the Philippines and bypassing thorny Yap, but Nimitz found nothing in the fleet commander's report that tempted him to cancel Peleliu.

During his sleepless hours, as he studied the maps and charts of the Palaus, Nimitz surely saw compelling reasons to wrest their control from the enemy. The Japanese maintained at Koror the headquarters for all their Pacific islands mandated by the old League of Nations. Kossol Passage, to the north, was a decent protected anchorage. If Babelthaup was too large and defended too heavily, Peleliu was certainly a suitable alternate objective because it was smaller, could be invested by the task force, and had a first-class airfield. Nimitz could readily see that seizing Peleliu would remove all these Japanese capabilities from the board and bottle up tens of thousands of troops on Babelthaup and throughout the western Carolines, including Yap. As Nimitz had been testifying for months, U.S. forces might be able to take Ulithi without Yap, but it could not be done without first taking Peleliu. Possession of Peleliu's airfield—and construction of a heavy bomber strip on the flat terrain of nearby Angaur—would permit Nimitz to support MacArthur, suppress Yap, protect Ulithi, and project reconnaissance and bombing missions far to the northwest as well.

Here, the factor of overconfidence likely weighed on Nimitz's decision. Arguably, he could have assigned one of Mitscher's carrier task groups to spend the rest of the war rendering the Palaus toothless from the air, but Nimitz believed it to be a more efficient use of his assets to seize, occupy, and defend Peleliu with his veteran landing force. Where Nimitz's earlier assault landings at Tulagi, Gavutu, and Tarawa had been executed at painful cost against fiercely resisting rikusentai (Japanese special naval landing forces), his principal opponents in the Marshalls and Marianas had been units of the Imperial Japanese Army, good fighters but led poorly in those battles. Ill-advised, grandiose Japanese counterattacks at Saipan and Guam had served only to accelerate the U.S. victories against an otherwise hidden and deadly enemy. At Tinian, the most recently executed landing before Stalemate, the Marines had seized the island in nine days, inflicting a casualty ratio of four-to-one against the defenders.

Throughout the war, Nimitz kept posted over his desk a small sign whose lead question asked "Is the proposed operation likely to succeed?" Based on what he knew and assumed on 13 September 1944, the imminent invasion of Peleliu had every likelihood of success at an affordable cost.

The resulting carnage at Peleliu doubtlessly shocked Nimitz as it did the amphibious force. And while tactical errors were committed by senior Navy and Marine officers who should have known better, the greatest shortfall of the campaign proved to be unsatisfactory combat intelligence.

Theater intelligence teams published the precise enemy order of battle at Peleliu weeks in advance, but Nimitz, Halsey, and the Western Attack Force were served poorly by the omission of two critical enemy factors. No one knew that they would be facing one of the best-trained, best-led infantry regiments in the Imperial Army; or that in Colonel Kunio Nakagawa the Marines would fight against a commander surpassed only by Iwo Jima's Tadamichi Kuribayashi as their most redoubtable opponent of all time, a colonel with such an eye for terrain and such a gift for close combat that the Japanese government promoted him posthumously to lieutenant general. Nor did anyone appreciate the fact that the Japanese had just modified their counter landing tactics. The Japanese at Peleliu would introduce the U.S. invaders to cave warfare, deep positions arrayed in honeycombed echelons, a new war of attrition. The tortured terrain of the Umurbrogol provided a perfect setting.

Into this lethal landscape came an overconfident landing force, whose assault numbers barely equaled the defenders (much less the three-to-one ratio found necessary for success in earlier operations), whose operational reserves were too few and committed too readily to lower priority missions against Angaur and Ulithi, with preliminary naval gunfire support reduced nearly to Tarawa levels, and with insufficient tank and mechanized flame-thrower assets. That the Marines and Soldiers eventually prevailed under these conditions is a tribute to their small-unit leaders and individual riflemen. That the bulk of the fighting was conducted at such close ranges that the Marines, to cite one example, expended 116,000 hand grenades, is not surprising. Nor is the fact that the operation cost 9,600 casualties and took ten weeks to complete.

Halsey's reaction to Nimitz's decision was muted. On D-Day at Peleliu he wrote his commander ("My dear Chester . . .") expressing delight at "the prospective speed-up of the war," but avoiding mention of the Palaus. As the battle progressed, Stassen recalled Halsey discussing the high casualties and wondering if he should have made one final effort to persuade Nimitz to cancel Peleliu, "but then he concluded it was too bad, that they had `pushed it to the edge' and gotten as much concession from Nimitz and the Joint Chiefs as they had a right to expect."

Halsey visited Peleliu on 30 September, 15 days after D-Day, appalled at what he saw and shaken by a near miss from a Japanese mortar shell. A week later he downplayed the experience in brief mention at the end of a routine letter to Nimitz, saying: "Peleliu and Angaur were the usual thing on recent visit. The interconnecting caves in the hills, with many entrances and exits, and various connecting tiers was a new phase. It is a slow progress in digging the rats out. Poison gas is indicated as an economical weapon."

Nimitz did not visit Peleliu, the only major beachhead he skipped. Nor did he engage in public discourse when Halsey declared the campaign an unnecessary mistake in his outspoken postwar memoirs. Nimitz's sole retrospective consists of a 1949 note to historian Philip A. Crowl in which he cited two purposes for seizing Peleliu: "first, to remove from MacArthur's right flank, in his progress towards the Southern Philippines, a definite threat of attack; second, to secure for our forces a base from which to support MacArthur's operations into the Southern Philippines."

Bloody Peleliu lasted longer than the other two most desperate assaults in Marine Corps history—Tarawa and Iwo Jima—but it produced the fewest visible strategic benefits. Many veterans became more outspoken as the years passed. Said former Marine mortarman Eugene B. Sledge in 1994: "I shall always harbor a deep sense of bitterness and grief over the suffering and loss of so many fine Marines on Peleliu for no good reason."

Yet Peleliu was not devoid of redeeming values. Ulithi became a superb advance naval anchorage for the Iwo Jima and Okinawa invasion fleets. A Peleliu-based search plane found the forlorn survivors of the sunken cruiser Indianapolis (CA-35) in August 1945. Capture of Peleliu effectively bottled up some 43,000 other Japanese troops in the neighborhood without a fight. And the tactical lessons in cave warfare learned at such cost by the III Amphibious Force proved invaluable in the struggle for Okinawa a half-year later. In fact, the 1st Marine Division's masterful use of tanks, flame-throwers, siege guns, and close air support during its fierce battles for Awacha Pocket, Wana Draw, and Kunishi Ridge made a world of difference in the Okinawa campaign.

Lacking all this hindsight, Nimitz made the best decision he could with the information available at the time. The subsequent unpleasant surprises and terrible costs were painful to bear, but the result was a clear victory. Nimitz succeeded in driving another stake into Imperial Japan's heart, a chilling warning that U.S. forces could prevail despite the most ingenious of defenses and skillful of island commanders—even on a bad day.

Colonel Alexander, an award-winning author and historian, is grateful to Scott C. Anderson, Isao Ashiba, Lieutenant Commander Jon T. Hoffman, U.S. Marine Corps Reserve, Mary C. Hoffman, Commander H. Arthur Lamar, U.S. Naval Reserve (Retired), Bunichi Ohtsuka, the Honorable Harold E. Stassen, Paul Stillwell, Paula Ussery, and Peleliu survivor Ei Yamaguchi for their assistance in preparing this article.