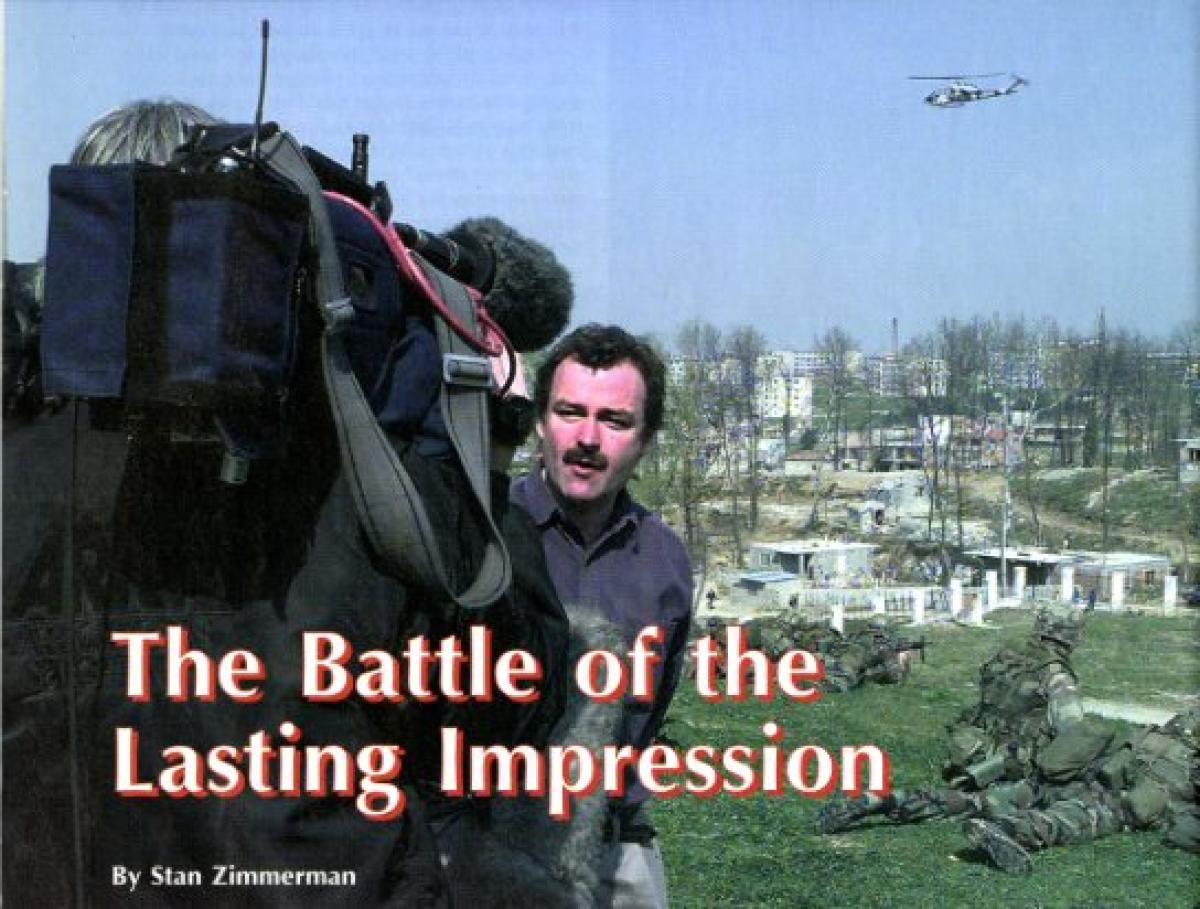

With their growing power to sway public opinion, the media have become part of the military strategists' decision cycle. To use this relationship wisely - this news team is reporting from the U.S. embassy complex during evacuation operations in Albania - the Navy must understand and appreciate the press as never before.

We are living in a new era. Naval power has grown in scale and scope until individual conference rooms or entire societies can be obliterated by strikes from the sea. And just as naval power has grown, so has the power of the press to sway critical individuals and mass populations. Even as military strategists labor to move inside an opponent's decision cycle, the news media have become part of both their decision cycles - arguably, an even more powerful position.

In times of crisis, national leaders turn to the Cable News Network to augment (and check) their intelligence resources. The proliferation of real-time, all-news outlets-television, specialized e-mail editions, and the Internet-will only increase the depth and detail of information and misinformation available.

With the shift to stealth in naval and airborne platforms, military demonstrations in the future will be forced to use the press release instead of the port call to deliver a political message. Submarine-launched cruise missiles can demolish with impunity an enemy's ability to wage modern war, but for this capability to retain value as a deterrent, the threat must be communicated and believed, not only by the opponent but also by domestic populations.

This type of communication is an aspect of information warfare defined in classical terms as "white propaganda," because the source is unambiguous. It is a new environment for the military, and a new national security role for the press. For the Navy to use this relationship wisely, it must understand and appreciate the press as never before.

On the Front Lines

Traditional news reporting is a trade, much like carpentry or pipe fitting. Apprentice reporters are called "cubs," and cubhood usually is a wrenching experience. Before it's over, the young reporter will witness some of the ugliest sides of human life. The first murder scene, the first interview with a rape victim, and later the first crooked cop, the first feet of clay on a public figure these are milestones along the way to journeyman status.

Most practitioners remain journeymen, toiling at small and medium-sized broadcast and print operations, chumming with cops and politicos, grousing about who covers this year's flower show. Some cover the Navy at the local level.

Some graduate to bigger cities, and the best end up in Washington—the journalism capital of the world. They continue to chum the cops and politicos, only on a grander scale. A very few of them are assigned to cover the Navy.

In addition to the traditional career path, Washington offers another approach. Folks with fresh journalism degrees disregard the advice of their mentors to begin their careers in the hinterlands, and instead they jump directly into the D.C. press corps, usually for small and specialized publications. They lack the seasoning and balance of journeymen reporters, and when assigned to cover the Navy, they represent a special problem because their small publications are mined for "tips" by others serving more general audiences.

Regardless of their publication or experience, most reporters work as skirmishers, operating alone under loose control. When they find a hard-hitting story - a schwerpunkt, in military parlance - they call in the regular troops by writing or broadcasting it. These regulars are the reporters of the national press corps; they are supported by field producers and anchors, fact-checkers and photographers, editors and extensive morgues, and hefty expense accounts for helicopters, satellite links, and other tools.

Behind the skirmishers and the regulars lies the heavy artillery-the perceptions of Congress and the public. The power of a story lies in the mind; until it is acted on, a story is only a collection of words and images. It is in the mind where we find the crucial battleground of information warfare.

The Penchant for Secrecy

There is a widespread perception in the Navy today that the press is the enemy. Rough treatment in stories about the Vincennes (CG-49) and the Iranian Airbus, the turret explosion on board the Iowa (BB-61), and the Tailhook gauntlet have scarred the service's public reputation for integrity. It is natural to view the agent throwing the punches as hostile.

Good reporters develop keen intellectual senses during their cubhood, and refine them throughout their career. Some call it a "nose for news," and others call it their "BS meter." One obvious scent is hypocrisy. When folks especially powerful folks-say one thing and do another, reporters detect a story.

On 7 March 1990, two senior admirals came before the House Armed Services seapower subcommittee to testify about the Navy's submarine program. The three-star read his statement and answered questions. Then the subcommittee chairman turned to the four-star, who spoke his first words at the hearing: "I'd like to have it closed." Press and public were escorted from the room. On 14 June, the same four-star, speaking before the Naval Submarine League, said, "The role of attack submarines needs to be better understood."

The admiral did testify publicly before the seapower subcommittee in July, but only after the General Accounting Office had published a blistering attack on the Seawolf (SSN-21) program. In August, Defense Secretary Dick Cheney cut the program in half, and in January 1992, he killed it. The same admiral called the decision "a fatal blow."

When admirals will fight publicly for what they believe in only under extreme pressure-in this case, criticism and then cancellation of a major program-it is difficult for the press and public to understand what the admirals believe and why. It also makes their public statements appear self-serving. Even short-term victory can lead to long term defeat.

In October 1993, in the aftermath of Tailhook, Secretary of the Navy John Dalton scrapped with Chief of Naval Operations Frank Kelso. Secretary Dalton wanted Admiral Kelso to resign. Admiral Kelso went over Dalton's head to save his job. "The Secretary of Defense overruled me," Dalton said. Admiral Kelso's term was truncated five months later when he resigned-for health reasons but he left behind the perception that he was hounded from office by the press. He also left behind a perception that senior admirals play by their own rules.

Admiral Kelso was replaced by Admiral Jeremy "Mike" Boorda in April 1994. The same month, Admiral Stan Arthur was picked to be Commander-in-Chief, Pacific. Admiral Arthur never made it, sacrificed on the altar of political expediency when he refused to let an unqualified aviation candidate continue training. Because the candidate was a woman in the post-Tailhook era, Admiral Arthur's decision caused his nomination as CinCPac to be withdrawn, and a long career punctuated by heroism was truncated.

Admiral Boorda's career, too, was cut short-by suicide only minutes before a scheduled press interview regarding his right to wear awards for combat service.

Three four-star admirals brought low by the press? Or were they brought low by their own actions as revealed by the press-or in the case of Admiral Arthur, by the actions of others under press pressure?

The Undercurrent of Intrigue

The media have punished the Navy in the past decade. Some go so far as to see a military-style campaign under way to discredit the nation's oldest uniformed service. In a sense, they may be right-but for the wrong reasons.

From the mid-1980s until well into the Tailhook episode, the Navy played a disingenuous game with the press. One writer in these pages called it "winning the battle of the first impression." His logic depended on an immediate response using a plausible cover story; it then depended on the rush of other news to wipe the story from public attention. "Put a good face on it and it will blow over" might sum up the strategy.

Thus, we have a gay battleship sailor bent on revenge suicide on board the Iowa, an Iranian F-14 "diving" at the Vincennes, and "boys will be boys" manning the Tailhook gauntlet. None of these initial explanations withstood the scrutiny they deserved and received.

For those who don't follow the news closely, these "cover stories" remain intact. For those who care about public events, the outcome was much different-the Navy was not telling the truth, probably knew it was not telling the truth, and wasn't to be trusted.

This was not just a problem for Navy public affairs; mendacity began to percolate through the Navy-industry sector. In March 1990, as part of his Major Aircraft Review, Defense Secretary Dick Cheney visited the St. Louis facility where the Navy's stealthy A-12 medium attack bomber was under development. Workers rounded up every major part they had made for the A-12, and pushed them together on the shop floor. Landing gear was brought in from the subcontractor. Virtually every part was defective, orange and red tags stuck all over them. All the tags were removed, and when Cheney walked through the A-12 facility, he was greeted by what appeared to be a virtually complete aircraft. It was a Potemkin village, pure and simple.

Only weeks after his visit, Secretary Cheney testified before Congress that the A-12 was on time and on track. In subsequent court testimony, he said of his visit to St. Louis: "It was an upbeat presentation, and the program was going forward and in good shape."

Congress knew nothing of the ultra-secret program. It had only the word of the Defense Secretary. And that word - as we now know - was wrong. Secretary Cheney didn't lie; he just didn't know any better. He had been deceived by two major defense contractors and any number of naval officers and civilian leaders, including, as the record shows, the Secretary of the Navy, who remained silent as Secretary Cheney crawled out on a rotten limb.

One month after his congressional appearance, the bough broke. Secretary Cheney was told on 1 June - by the contractors, not the Navy - that the A-12 program was far over cost and far behind schedule. He was forced to go back to Capitol Hill and change his story. As a result, not only did Secretary Cheney want to know what was going on inside the Navy, now Congress did, too. Both launched investigations-and the program was terminated.

The political impact of the A-12 debacle will linger. As one congressional staffer put it at the time, "We have a lot of new people here [on Capitol Hill], unscarred by those past scandals over toilet seats and hammers. This is a million times worse, and it's going to be remembered."

Profiting from the Mistakes

In the past decade, the Navy has waged information warfare against the American press, the Pentagon bureaucracy, Congress, and the public at large. As evidenced by its battered reputation among these same "targets," it is clear that the Navy has lost the campaign.

One example of the depth of this defeat came from a focus group hosted in 1990 for the Naval Recruiting Command. When presented with 100 pictures of men and asked who likely would be sailors, the focus group picked "four geeks, a bartender, and a homosexual on the beach," said the director of the command. "We don't have an image."'

There are profound differences between the cultures of the Navy and the media. Because there cannot be "order and discipline" in the ranks of a free press, the Navy must adapt its tactics-and perhaps even change its culture-in response to the demands of information warfare.

Credibility is crucial. A Marine on patrol must trust the man on point, just as a sailor must trust his colleagues at a faraway warfare center to devise safe munitions. Mendacity is a corrosive, and permeates swiftly down from the highest ranks. "Gosh, if the Secretary of Defense can mislead Congress, why should I tell my chief about this?"

Navy Secretary John Dalton says repeatedly, "Integrity is a readiness issue." If you can't trust your shipmate, your captain, your admiral, how can you fight?

For many in the Navy, the safe response has been no communication at all, in a sense abdicating the battlefield. For years, senior admirals declined interviews with the press, but this has begun to change. "There is a significant fear of the press here, and I think we have to get rid of it," one senior admiral said in a recent interview. "When I came to Washington, I decided not to talk to the press. In the last two years, I've changed my mind. We've got a story to tell, and I think we ought to tell it."

The effort already has begun. There are more embarkations available for reporters. Interviews are easier to obtain. Information is more accessible via electronic bulletin boards, official newsletters, and web sites. This is commendable, but there is more to be accomplished before the decade of disaster is undone.

Reporters should be allowed inside nuclear shipyards. It is difficult to sustain the claim of "crown jewels" when the view comes from outside a chain-link fence. Commanders should seek out "the enemy" by holding regular press calls, perhaps on a not-for-attribution basis, to meet the men and women who cover their bases, their squadrons, their laboratories or divisions. The news media - specifically the reporters who cover the Navy - are the conduit for the explanation of sea power to the American public and the world at large. Their improved understanding will spread.

It would be useful to include reporters who demonstrate knowledge of naval matters in war games as players, and allow them to write about their experiences. Seminars open to the press and public on such topics as antisubmarine warfare, fundamentals of naval operations, or aspects of naval research are feasible; many such seminars today are classified, although participants say most of the material presented isn't.

An orientation for reporters new to the Navy beat - something as basic as a handout or as complex as a night school, college-level course - should be organized. A public information officer should be eager to meet the newest reporter on the Navy beat, and to offer him something tangible - a list of contacts, a table of organization, a Navy fact book, a story idea. Corporate press relations folks do it all the time.

It is vital that the Navy offer to increase the depth and breadth of communication with the news media, to further understanding on both sides. If nobody shows up for the press call or night school, so be it. The Navy can say it tried. Burned bridges should be rebuilt with opportunities, but it will take time, patience, and tenacity.

New Press Roles and Responsibilities

The press, too, must adapt to the new realities of information warfare. One role is personified by Edward R. Murrow reporting from the rooftops above a heavily bombed, burning London, defending-even urging on the fight against fascist tyranny. Although an icon for generations of reporters, Murrow was as much a propagandist as Frank Capra, director of the "Why We Fight" series.

Or is the future role to be that of the disinterested observer, the quiet fellow in the back with no dog in the fight, notebook at the ready-the dispassionate reporter of every scrap available regardless of consequence? How do we prepare the polyglot press for its growing importance in the emerging and already-powerful field of information warfare?

For starters, military reporters should be qualified to follow the troops. Each combat element - paratroops, submarines, aviation, etc. - should be allowed to establish a short training course to qualify reporters who wish to accompany soldiers and sailors into harm's way. Americans expect and deserve reporting from the front. Predigested press pool dispatches and in-theater press conferences are poor substitutes for frontline reporting.

Commanders are naturally loath to put a reporter in danger, but for a combat correspondent, that's where the stories are, and that's where-by hook or by crook-the best reporters will gravitate. Commanders should accept this fact, and prepare for it.

Qualifying reporters in peacetime-in ejection seat procedures, weapon safety, fieldcraft, damage control, emergency breathing, SCUBA, parachuting - satisfies many objectives. The training will expand personal contacts between reporters and "operators" - as opposed to military bureaucrats - allowing reporters to understand that the most important people in the military don't operate from swivel chairs. By being honed themselves, they will gain an appreciation of how sharp is the end of our spear.

It will increase a field commander's confidence that he will not impede his mission or endanger the lives of his men and women by taking a loose cannon on board. And it will allow the synchronization of the equipment needed for the reporter to file his story. Technicalities like satellite link frequencies, message formats, routing instructions, and digital compatibilities all can be checked and streamlined, so reporters can move their stories with minimal interference to the warriors.

Military-style training is rugged, and should be. Such a qualification process can separate the capable from the incompetent, the dedicated from the wannabes, the professionals from the armchair critics. Today's military requires technically proficient, agile fighters; should we accept less from the military press corps? By qualifying, reporters enhance their credibility with their readers as well as with the military, and they earn the logistical and communications support they will require when it's time to do the dangerous and dirty work of war correspondency.

There are no honest brokers in information warfare. It is not a "fur me or agin me" environment, because information is widely diffused in our data-rich society. It is what operators do with this information-what it leads them to believe and act on-that closes the decision loop. A reporter broadcasting from a hostile capital is no less a resource than a satellite photograph or the intelligence report of a mole.

We are at the infancy of information warfare. The Navy's experience of the last decade is a case study of trial and mostly error. The leadership needs to devise a better strategy. When the Chief of Naval Operations goes on television someday to warn a foreign leader that a fleet of submarines is prepared to make him pay, we don't want the leader - or the anchorman - saying, "Oh, it's just those Navy guys again."