On 19 February 1996, I heard that a wonderful young officer, Lieutenant Commander John “Stacy” Bates, his back-seater, and three civilians on the ground had been killed in an aircraft accident involving the F-14 Tomcat. Shortly after I received the news of his death, I was able to read a transcript of the Secretary of Defense’s follow-on press conference. At least twice in the transcript, a “Topgun mentality” was mentioned, as if to define Stacy Bates by implying a cavalier and dangerous attitude toward the operation of tactical aircraft. My purposes are twofold: To help people understand just who Stacy Bates was, and what motivated him; and to define what the true “Topgun mentality” means to me and to carrier naval aviation.

Details surrounding the aircraft accident will be forthcoming soon. I want to believe that it had nothing to do with a lack of concentration or a cavalier attitude, as some pundits already are claiming. From the recent F-14 accident involving Lieutenant Kara Hultgreen, the interested and informed segment of the public is aware of the process through which the Mishap Investigation Report is constructed. There will be a Judge Advocate General’s investigation conducted in the Bates case, as well. Most of us in naval aviation have abiding trust in the expertise and objectivity of the Mishap Board. Its members will spend hundreds of hours poring over records and data from the accident site, attempting to reconstruct the final seconds of this fatal flight. Until the report is completed, there will be a great deal of conjecture about what may have happened. Most of it will be negative; these days, that seems to be the conventional drift whenever the subject is carrier naval aviation.

As a naval aviator, presently attached to a deployed battle group staff, I am qualified to comment on both this accident and the larger picture of naval aviation—owing to my association with the mishap crew and its squadron and my desire to see continued success for naval aviation in the years ahead. After nearly 20 years of flying the Tomcat during eight carrier deployments I have been close to and personally involved in similar mishaps, and those involved in them—and feel well-qualified to discuss this particular one.

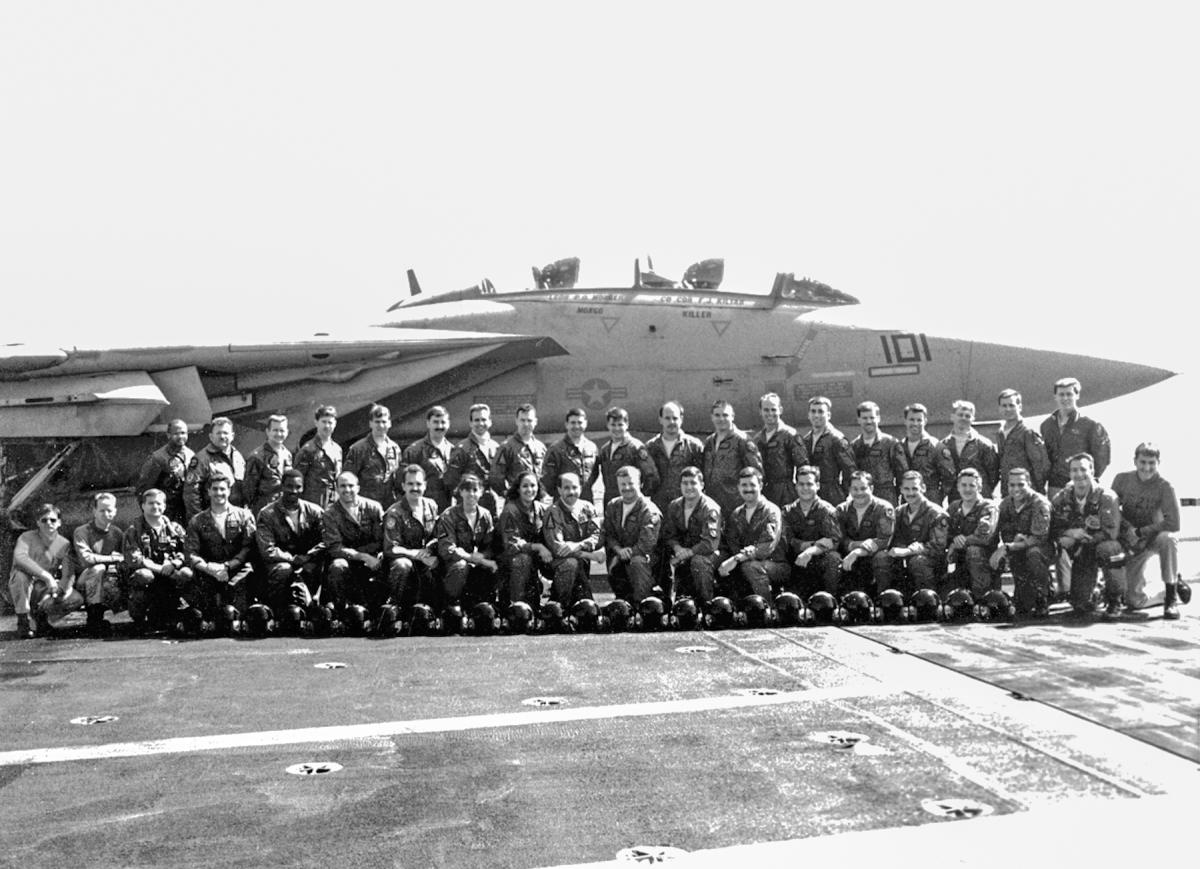

I first came to know Lieutenant (junior grade) Stacy Bates in 1986, when he checked into his first squadron as a radar intercept officer. He was a talented, enthusiastic, and committed gentleman, singularly loyal to the command and to the U.S. Navy. I followed his career through pilot transition and his return to Naval Air Station Miramar in 1992. At the time, as the Commanding Officer of VF-213 (the "Blacklions”), I was intent on bringing the most talented and dedicated aviators and technicians I could find into the command. I asked Stacy and his wife Christina to join the squadron. My direct association with Stacy continued through my change of command, in March 1994. While he served in my command, Stacy established himself as everything I had hoped for. Although he was, essentially, in his first tour as a pilot, his experience as a carrier aviator and his desire to be the very best possible Tomcat pilot were evident every day, both on the ground and in the air. He absolutely was the hardest-working junior officer in the entire air wing. No one pushed himself harder. He was one of a kind—both as an officer and an aviator.

In carrier aviation, there are “natural” aviators and there are those who must work extremely hard to become as good as they can be. Often, the natural aviators are not the best ones; they work less hard than the less-gifted ones to reach the same goals—and they can get complacent. Stacy, on the other hand, was the kind of aviator who worked with exceptional diligence and who far exceeded the capabilities of many natural aviators. In fact, I saw a lot of myself—as a young F-14 pilot—in Stacy. Stacy worked tirelessly to establish himself among the very best through strict attention to established procedures and rules. He was not a maverick; he was simply a young man trying to be the best in a highly competitive community that scrutinizes each member every day—and seldom lets its pilots rest on their laurels.

To attach a negative “Topgun mentality” label to any of these splendid aviators is a grave injustice, but such labels have been freely attached ever since Tailhook ’91. The scars of this Tailhook debacle will take a generation or more to heal. Every individual who even attended the convention has been tagged with some derisive version of the ‘Topgun mentality.” I often have been asked to explain the circumstances of and events leading to the crisis of faith caused by the Tailhook incident. I also have tried, unsuccessfully, to understand how carrier aviation could go—in one short year—from the peak of post-Desert Storm accolades to the valley of post-Tailhook floggings that the community has received and continues to receive.

Every fledgling carrier aviator understands that he is held to a much higher standard than the college fraternity brothers he may have lived with a year or two before he became a naval aviator. Acceptable norms of behavior on some campuses are not accepted in naval aviation, and never have been. A molding process must take place to ensure that every young aviator lives up to those higher standards and this process takes a measurable amount of time. The troubles at any Tailhook convention, including the one in 1991, usually stemmed from the conduct of a small fraction of officers, most of whom had never been deployed at sea; they were still in training to become aviators, and were waiting for their opportunity to prove themselves in the community. The accomplished fleet aviator, on the other hand, has been tempered by close calls with disaster and a self-scrutiny defined by a certain loss of naivete and born of tests of will, of concentration, and of stamina. A certain, indescribably effective, molding process has taken place.

With Stacy Bates, no molding was required. He was the epitome of a carrier naval aviator from the very start. Most carrier aviators who have been to sea are subdued and thoughtful, compared to the young men who are still just earning their wings. And Stacy was one of the subdued, thoughtful ones. The few who are not part of that mold are real aberrations.

Many may look at Stacy’s earlier loss of an aircraft and say that he should not have flown again. Let me assure you that there are many highly successful carrier aviators—current and retired—who have at one time or another lost an F-14 Tomcat. Loss of an aircraft—unless it occurs through gross or premeditated negligence—never has meant immediate condemnation of the mishap crew. Traditionally, the F-14 has been a demanding aircraft to fly, both around the carrier and in combat training. The Tomcat has a number of dangerous stability characteristics, and if it is not flown with the utmost care and attention the result can be tragic. The very few aviators who have blatantly disregarded the dangers of a highly maneuverable and dynamically unstable fighter aircraft or who have broken the established rules of aviation conduct—and have thereby lost an aircraft—have not been allowed to continue in naval aviation.

What, then, is the real “Topgun mentality?” I was fortunate enough to spend seven months as a Topgun instructor at the Navy Fighter Weapons School in 1982–83. To be a part of the institution that was so successful during the Vietnam War in training fighter aircrews was a real honor. Never have I been associated with a more professional, highly talented, intensely dedicated group of aviators. For three-year tours, 14–16 hours a day, often seven days a week, the staff instructors literally struggled to perfect the lectures and training regimen for the fleet aviators.

The standards expected of every Topgun instructor, and consequently of each student, remain higher than those of any other organization in aviation—or the entire Navy, for that matter. I have never been as inspired, nor do I expect I ever will be again. This is the essence of the Topgun mentality as I—and many others who have been a part of this community—see it.

The objective, and essence, of the Navy Fighter Weapons School is to create leaders who can return to their commands to teach other aviators, both junior and senior, to meet the Topgun standards. The Navy Fighter Weapons School continues to be the envy of every other military training organization, and it maintains quality by accepting only the very best students for the six-week course of instruction.

Stacy Bates was selected to attend that course of instruction, and he subsequently returned to his command to instruct other aviators about the current threat and how to defeat it decisively. No doubt, Stacy was the hardest-working student in the Weapons School for some time, and his diligence truly defines the Topgun mentality.

Every day of the year, on every carrier deployed overseas, there are nearly 300 young aviators on six- month deployments, braving extreme conditions, night arrested landings with no divert field in the middle of the Indian Ocean or North Atlantic, where the deck can pitch 30–40 feet in a cycle. Yet the leadership still launches the aircraft, and the young men and women launch without question, because that is what they are expected to do. In fact, they revel in the challenge of it all. As George Will has observed in his commentary on carriers at sea, most Americans do not realize the personal sacrifice, the danger, and the potential combat that each carrier naval aviator faces every day of a six-month deployment.

This lifestyle does demand an individual who must have supreme confidence in his own abilities, yet maintain a high respect for the aircraft he flies, and the conditions through which he has to operate the aircraft. It also creates a bond among these warriors that is not experienced in many other walks of life. Yes, there has to be a sense of purpose for an individual to want to make a career of this. He does it for love of flying, for the camaraderie of his associates, and for the love of his country. This is the true Topgun mentality, the one Stacy Bates acquired so early on in his professional life.

Admiral J. M. Boorda, the Chief of Naval Operations, recently remarked about the mishap:

1996 to date, even with this tragic mishap included, is safer than any (year) we’ve experienced. So, even as we mourn our loss, even as we work through what must be done, it is important to remember that. I’m not telling you this to lessen the impact of this mishap . . . nothing can do that. Instead, I’m telling you this because I want you to know that Naval Aviation is a professional outfit, competent and capable and that even as we work through this, we must remember that fact.

The future will not change. Carrier naval aviation will always produce young men of the caliber of Stacy Bates. The nature of the warrior will always differ from other subcultures in our society. In time of peace, you can modify that culture. In time of war, the culture will return to its centuries-old demeanor of self-reliance, absolute courage under fire, and a certain acceptance of feelings of immortality and callousness, as defenses against its potential losses in combat. Preparation for combat must continue to instill some of those virtues, and they are indeed virtues. To those who believe that today’s training is being stripped of those virtues, let me assure you that today’s combat aviator is better trained and more highly competent in every mission area than even five years ago, and still possesses the spirit of a brave heart and an indomitable will to win that these virtues instill in him.

For those of us in the community, recent damaging events have failed to diminish our respect for the institution of carrier naval aviation. More important, they have caused us to demand more of ourselves to ensure and strengthen the integrity of the community that so many of us hold so dear to our hearts. The community never wants to have to apologize for the actions of a very few, ever again.

In the truest sense of the meaning, the Topgun mentality is a positive force—the one which will ensure that carrier naval aviation not only survives, but prospers.