Captain Mohsen Rezaian was piloting his fully loaded Iran Air Airbus airliner through 13,000 feet on a routine Sunday morning flight across the Persian Gulf to Dubai, when a burst of shrapnel ripped off the left wing and tore through the aft fuselage.

We shall never know Captain Rezaian's last moment, but in that instant before oblivion he may have looked in horror out his left window and thought that the stub of flapping aluminum and severed hydraulic lines where the wing had been was the result of some sort of structural defect.

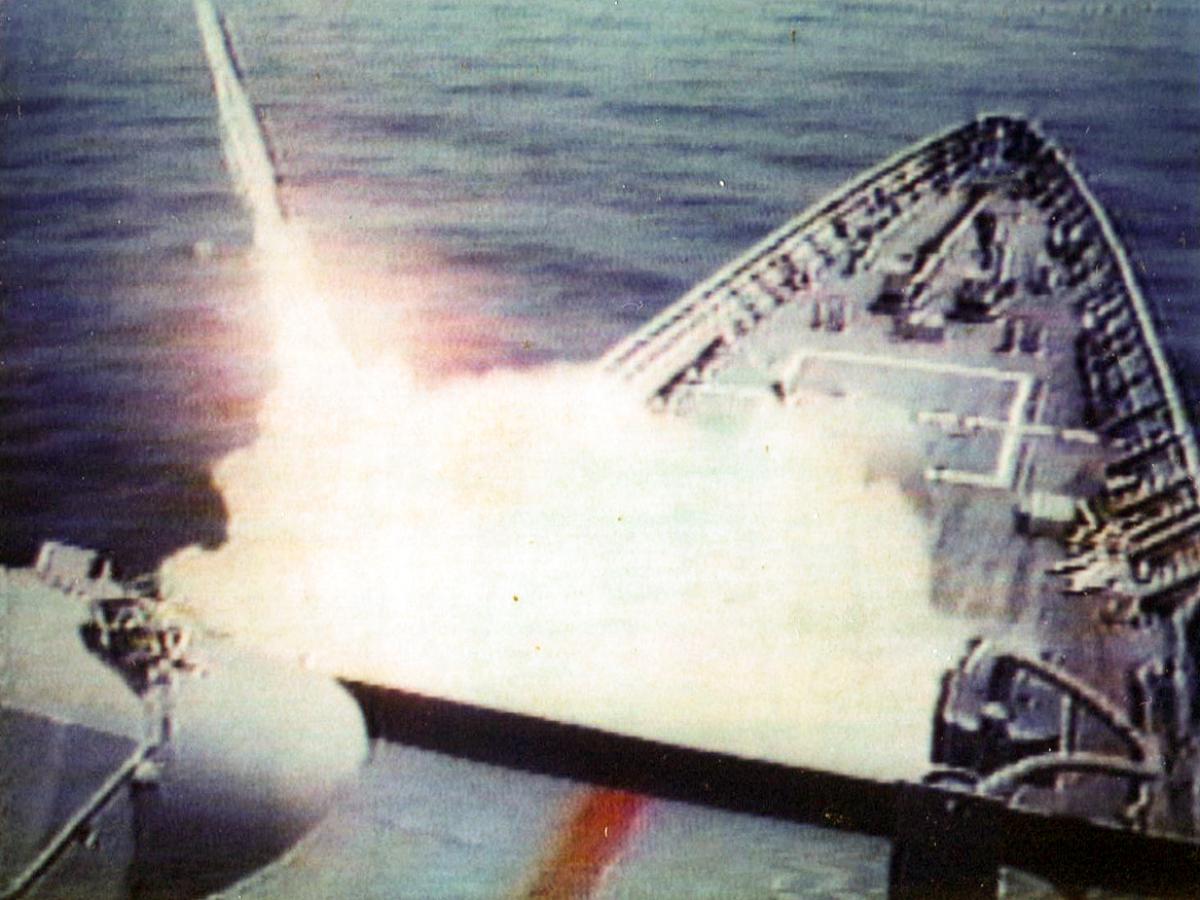

It is doubtful that he ever saw the two fiercely burning points of light streaking up at his airplane, the Standard missiles launched by the cruiser USS Vincennes (CG-49).

It is also doubtful that Captain Rezaian ever heard the warning messages broadcast by the Vincennes, or by the frigate USS Sides (FFG-14), about 18 miles from the cruiser. The two ships were broadcasting on military and international air distress frequencies, and during the busy climb-out phase of his flight, Captain Rezaian likely was monitoring the approach control frequency at Bandar Abbas, where he took off seven minutes before, and air traffic control at Tehran Center.

If he had been monitoring the distress frequencies, the American-educated Captain Rezaian, although fluent in English, might not have known that the warning transmissions were intended for him. Indeed, as the Navy's report to the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) would later state, only one transmission made by the Sides just 40 seconds prior to the Vincennes' missile launch, was clear enough that it could not have been mistaken as being intended for another aircraft.1

Besides, Captain Rezaian's Mode III transponder, the civilian equivalent of the military's "identification friend or foe" (IFF) electronics, was broadcasting the unique code of a commercial airliner.2

Flying at a speed of about six miles per minute, the Iranian pilot had no way of knowing that moments earlier he had crossed the 20-mile point where Captain Will Rogers, the skipper of the Vincennes had announced to his crew and to other U.S. naval elements in the area, that he would shoot if the Iranian aircraft did not change course. Captain Rezaian could not have guessed that by now his lumbering A-300 Airbus had been evaluated in the Vincennes as a diving Iranian F-14—the spearhead of a "coordinated attack" from the air and from gunboats on the surface—and that Captain Rogers had given him an un spoken momentary reprieve by waiting until the airliner was 11miles from the Vincennes before he authorized the firing of the ship's SM-2 antiaircraft missiles.

As torn aluminum and 290 bodies from the shattered airliner rained down on the waters off Qeshm Island, the pieces fell into place for Captain David Carison, who as a commander then was skipper of the frigate Sides. This curious track number 4131, designated an Iranian F-14 by the Vincennes, simply had not behaved like a combat aircraft.

Indeed, as Captain Carlson would learn minutes after the Airbus plummeted into the water, the electronic specialists in the Sides' combat information center had correctly identified the aircraft's commercial transponder code at virtually the same instant that the Vincennes fired her missiles.

Captain Carlson recalled their exclamations: "He shot down COMAIR [a commercial aircraft]!"

To Captain Carlson, the shootdown marked the horrifying climax to Captain Rogers' aggressiveness, first seen just four weeks before.

The Vincennes had arrived in Bahrain on 29 May and got under way for her first Persian Gulf patrol on 1 June. On the second day of this patrol, the Vincennes was on the scene when an Iranian warship (the frigate Alhorz) had stopped a large bulk carrier (the Vevey) and had dispatched a boarding party to search the merchantman for possible war material bound for Iraq. Although it was within the Iranian skipper's rights to do so under international law, this appeared to be the first search-and-seizure of the Iran-Iraq War.

Simultaneously, the Sides was transiting out of the Persian Gulf to rendezvous with an inbound merchant vessel for a routine escort mission. Then-Commander Carlson had arrived on board the frigate by helicopter only four days earlier to relieve Captain Robert Hattan. Both men were in the Sides' combat information center (CIC).

As the Sides approached the scene, it appeared to Captain Hattan that the Vincennes was too close to the Iranian frigate. "Hattan didn't like the picture. We were not at war with Iran, and Hattan understood the need to deescalate a situation whenever possible," Captain Carlson would later relate.3

Nevertheless, the situation soon deteriorated when the Vincennes took tactical control of the Sides.

Captain Hattan recounted that "Rogers wanted me to fall astern of the Iranian frigate by about 1,500 yards. I came up on the radio circuit and protested the order from the Vincennes. I felt that falling in behind the Iranian [warship] would inflame the situation."

Captain Carlson added: "This event has to put in its proper context. Less than two months earlier, half the Iranian Navy was sunk during operation Praying Mantis, and our government had been making strong statements about America's determination to protect neutral shipping. Now what does the Iranian skipper see? He's conducting a legal board-and-search and here's an Aegis cruiser all over him. Next, an American frigate joins the action. Incidental to all this, Hattan knew that a U.S. reconnaissance aircraft was scheduled to fly over the area, which the Iranian might well detect on his air search radar. Hattan also knew that two other U.S. warships were behind us leaving the Persian Gulf. The Iranian captain would be seeing all sorts of inbound blips on his radar scopes, and he was alone."

"It was not difficult for Hattan to envision the Iranian skipper's apprehension that he was being set up. On top of that, let us just say that Sides' position relative to the Iranian warship was not tactically satisfying," Captain Carlson said.

Tensions increased. The Iranians, clearly skittish, fired warning shots at a civilian helicopter flying overhead with an NBC television crew on board.

"Hattan was very concerned that Rogers was going to spook the Iranian skipper into doing something stupid. He wanted out and recommended de-escalation in no uncertain terms," Captain Carlson said.

The higher headquarters at Bahrain, designated Joint Task Force Middle East, agreed and detached the Sides from the Vincennes' control and, in addition, ordered the cruiser to back off and simply observe the Iranian warship's activities.

This account stands in sharp contrast to the version in Captain Rogers' Naval Institute book, Storm Center, where he paints himself as the soul of caution. Captain Rogers described the incident as occurring during his second patrol, on 14 June, not 2 June, when he was barely into his first patrol. "Sensitive ground was being broken; no one wanted to escalate the problem," Captain Rogers wrote.4

Captain Carlson, who relieved Captain Hattan as commanding officer of the Sides, observes: "This confrontation happened on 2 June, and if anyone should get credit for cooling off a hot situation, it's Captain Hattan."

In a telephone interview, Captain Rogers agreed that 14 June is in error and 2 June will be used in subsequent editions of his book.

To Captain Carlson, it is not just a minor clerical error. "Rogers moved the June 2nd incident to the 14th and took credit for de-escalating the situation. But if the story is told as it actually happened, then Rogers comes across as a loose cannon on his first patrol. A junior four-striper [Hattan] had to set him straight and calm things down. The Alhorz incident was the beginning of all the concern about his ship," Captain Carlson said.

Although this incident was the genesis of the "Robocruiser" monicker hung on the Vincennes by the men on board the Sides, it was not mentioned in the formal investigation of the shootdown or in any of the subsequent testimony of senior naval officers to the public. The implications of the aggressiveness Captain Rogers displayed on his first Persian Gulf patrol were glossed over.

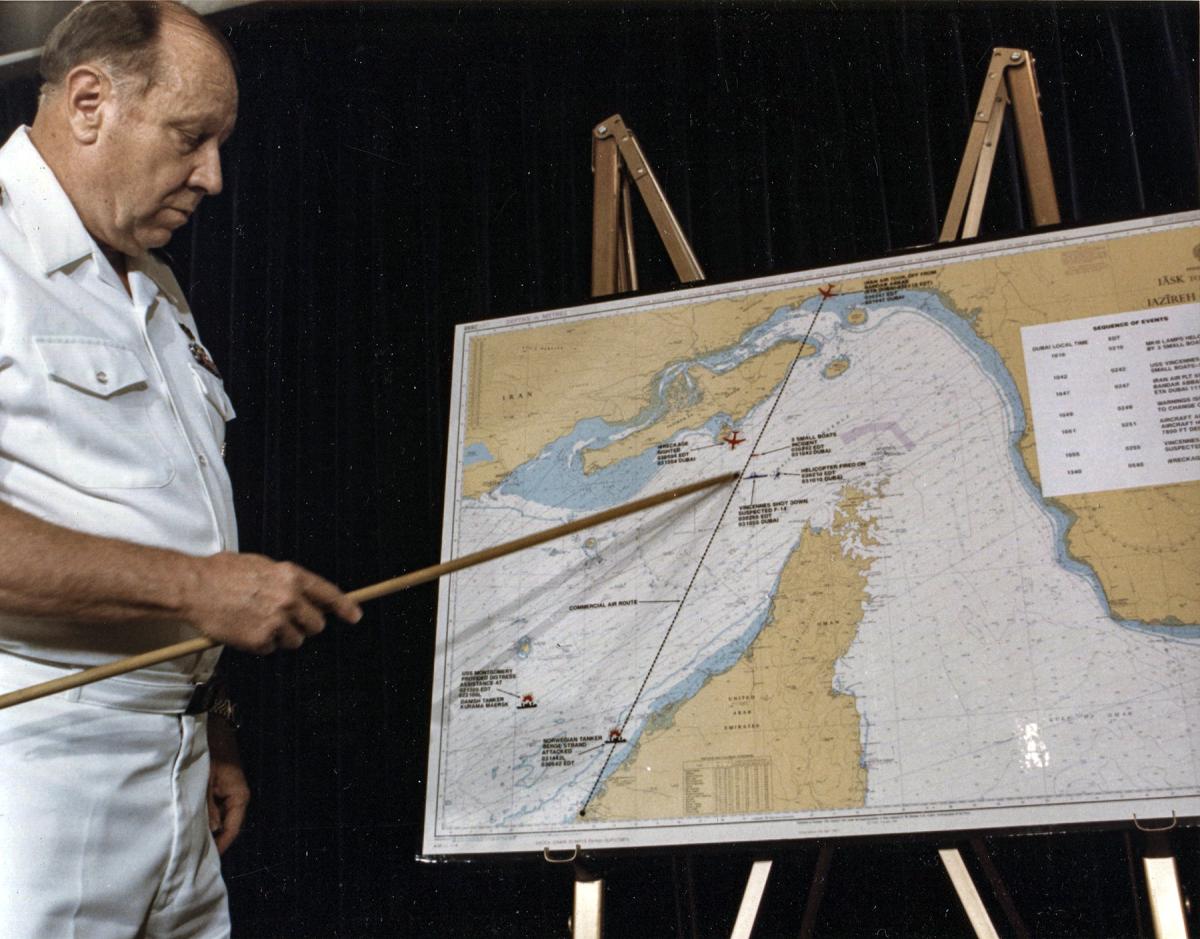

On the morning of 3 July, Captain Carlson and his men in the Sides' combat information center had a close-up view of the fateful train of events leading up to the shootdown of the Airbus. Unlike the USS Elmer Montgomery (FF-IOS2), the third U.S. warship involved in the events that day, the Sides was equipped with the Link-11 data link. This electronic system enabled the Sides and Vincennes computers to exchange tactical information in real time. Although they were 18 miles away, Captain Carlson and his watch officers had a front-row picture of virtually the same information that Captain Rogers saw on the large-screen displays in the Vincennes.

Shortly after sunrise, the Sides was on her way back through the Strait of Honnuz to rendezvous with another merchantman scheduled for a U.S. Navy escort through the narrow strait and into the northern Arabian Sea.

Over the radio, personnel on board the Sides heard reports from the Elmer Montgomery of Iranian gunboats in the Strait of Hormuz and in the vicinity of merchant shipping. "Montgomery reported sounds of explosions. There was vague discussion of some action taking place. Not much, but we were told by the surface staff [Commander Destroyer Squadron (ComDesRon) 25 in Bahrain] to increase speed and close the Vincennes’ position as fast as possible.”

Captain Carlson recalled, “Within minutes we got told, in effect, ‘Nah, that’s it, resume your normal speed.’ Fifteen minutes passed, maybe half an hour. Again, the word came down to the Sides to crank up speed and join the Vincennes. This order, too, was soon canceled.”

“I’m down in my CIC now, thinking, ‘Gee, this is starting off as kind of a fouled-up day, isn’t it?’ And then, lo and behold, the message came over the radio from Captain Rogers to the staff [DesRon 25] that his helicopter had been shot at,” Captain Carlson said.

Earlier, at around 0720, Captain Rogers had launched his helicopter with orders to fly north and report on the Iranian gunboat activity.

Also acknowledging the information, according to Captain Carlson, was the staff of the Commander, Joint Task Force Middle East, Rear Admiral Anthony Less. Admiral Less’s staff was on board the USS Coronado (AGF-11) at Bahrain. Captain Dick McKenna, commander of DesRon 25, and his staff were located on board the USS John Hancock (DD-981), at the Sitrah Anchorage in Bahrain.

“I smelled that something wasn’t good here,” Captain Carlson said. With good reason. Under the rules of engagement in effect at the time, the Vincennes’ helicopter, piloted that morning by Lieutenant Mark Collier, should not have been flying close enough to be threatened by the light weapons on the Iranian small craft. If Lieutenant Collier was in danger, it was because he was not following the rules: to approach no closer than four miles.

In a letter published last August, in the wake of a Newsweek magazine cover story on the incident, Lieutenant Collier wrote that he was never closer than four miles from the Iranian craft. However, that letter is at variance with Lieutenant Collier’s sworn testimony to the investigators, in which he conceded that he had closed to within two to three miles of the Iranian craft.5

In fact, when the investigating officer asked Lieutenant Collier, “You were actually inside the CPA [closest point of approach] that you were told not to go inside, is that correct?” Lieutenant Collier replied, “Yes, sir.”

With the report that the Vincennes’ helicopter had taken fire, Captain Carlson ordered his crew assigned to small-arms details topside.

“I was in CIC, and I remember my tactical action officer, Lieutenant Richard Thomas, saying, ‘My god, the Vincennes has really cranked up the speed here.’ You could see it, the long speed line on the scope. ‘Where the hell are they going?’ I was wondering,” Captain Carlson said.

When this question was posed in a telephone interview with Captain Rogers, he replied, “I wanted to get him [my helicopter] back under my air defense umbrella. That’s why I was heading north.”

This rationale raises questions. The Vincennes’ helicopter could dash away from danger at 90 knots, three times the speed of the advancing mother ship and, in addition, Captain Rogers already had control of the airspace his helicopter was occupying, some 19 miles distant given the extended range of his anti-air warfare weapons.

In fact, in the 3 August 1992 Navy Times, Captain Rogers offered a different explanation for his decision to press north. “Because of the bad atmospherics, any time the helo was farther than 15 miles, we lost contact,” he said.6

Captain Carlson recounted that “Rogers then started asking for permission to shoot at the boats. We already knew the helicopter was okay, and if the boats were a threat, you didn’t need permission to fire.”

Finally, after what Captain Carlson described as a couple minutes of “dickering” on the radio between Captain Rogers and the Joint Task Force staff in Bahrain, the Vincennes’ skipper was given permission to shoot.

“My executive officer [Lieutenant Commander Gary Erickson] and I were standing together; we both went like this,” Carlson said, pointing both his thumbs down. “It was a bad move. Why do you want an Aegis cruiser out there shooting up boats? It wasn’t the smart thing to do. He was storming off with no plan and, like the Biblical Goliath, he was coming in range of the shepherd boy,” Captain Carlson said.

Captain Carlson directed Erickson to go to the bridge and to sound general quarters. “On the way out, Gary asked, ‘What’s your worst concern?’ And I remember saying I was afraid that we might have to massacre some boats here,” Captain Carlson said.

“I mean, they were not a worthy adversary. Take a look at my ship, with a chain gun, 50-caliber machine guns, a grenade launcher, and a 76-mm. gun—all this against a guy out there in an open boat with a 20-mm. gun and a rocket-propelled grenade launcher. You’d rather he just went away,” Captain Carlson said.

The Sides continued to track the Vincennes whose speed line indicated high speed. At 0920 the Vincennes joined with the Elmer Montgomery and took the frigate under tactical control. The two vessels pushed north, with the Elmer Montgomery maintaining station off the Vincennes'port quarter.

On board the Vincennes, a team of Navy journalists recorded events as seen from the cruiser's bridge on a video camera. On the videotape, the Vincennes' executive officer, Commander Richard Foster, informed the combat information center, "We've got visual on a Boghammer," a reference to the Swedish-built boats operated by Iran's Revolutionary Guards. The camera zoomed in to an Iranian boat, which appeared dead in the water and floating between the Vincennes and Elmer Montgomery as they raced by.

The two U.S. warships held fire. They were headed for bigger game, the blips on the surface search radar indicating many more Iranian boats in the distance. According to the data later extracted from the Vincennes’ computers, it appears to have been a stern-chase situation, where the Iranian boats were headed toward the safety of their territorial waters.

As shown by the Vincennes’ videotape, the two American warships passed a second Iranian gunboat, this one to starboard of the cruiser. The boat’s crew can be seen relaxing topside. Hardly threatening behavior and the Iranians appeared not the least threatened by the passage of the U.S. Navy cruiser.

Yet at this moment, at 0939, Captain Rogers asked for permission to fire at Iranian gunboats he described as “closing the USS Montgomery and the Vincennes.”7

On the Sides, Captain Carlson was mystified. As he recounted in my interview with him: “Rogers’ actions didn’t make any sense on at least two levels. First, if he was bent on retaliation [for the shooting at his helicopter], why was Rogers waiting for a second demonstration of hostile intent? He could have engaged the boats he was pursuing at his convenience. Second, if the situation was so threatening, why ask for permission to fire? Under the rules of engagement, our commanders did not have to wait for the enemy to fire; they were allowed to exercise a level of discretion.”8

When he was asked about all this apparently unnecessary effort to obtain permission to fire, and the time it might consume, Captain Rogers offered a variety of reasons. To this writer, he stated, “It was engrained in our training to ask the boss.”9 However, on an ABC Nightline broadcast the evening of 1 July 1992, Captain Rogers related, “Time is a demon here. If I [sic] have a long time to sort things out, you are going to take more time to look at this, and more time to look at that. But when you don’t have time, you basically take what you have and…at some point in time you have to make the decision.”10 Yet in an interview later that month, Captain Rogers told a Navy Times reporter, “It’s always a good idea, if you have the time, to ask for permission.”

At about 0940, the Vincennes and Elmer Montgomery crossed the 12-mile line into Iranian territorial waters. There is no mention of this crossing in the unclassified version of the official report of investigation.11

According to the investigation report, at 0941 Captain Rogers was given permission to open fire. Note, he was now inside Iranian territorial waters and ready to engage boats that had not fired at him.12

From the data extracted from the Vincennes’ Aegis combat system, the Iranian gunboats did not turn toward the cruiser until 0942—after Captain Rogers had been given permission to fire. Time 0942 is the vital piece of information that destroys the myth that the Vincennes and Elmer Montgomery were under direct attack by a swarm of gunboats.

The time the Iranian gunboats turned was duly recorded by the Aegis data tapes, but it was not contained in the investigation report. Not until four years later, when Admiral William J. Crowe, U.S. Navy (Retired), the former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs, testified to the House Armed Services Committee on 21 July 1992, did this significant datum come to public light.13

Assuming his recollection is correct, Admiral Crowe said, “We actually know that they turned around toward Vincennes at time 42.” But Admiral Crowe then diminished the significance of what he just revealed by hastening to tell the congressmen, “I won’t confuse you with these times and so forth.”

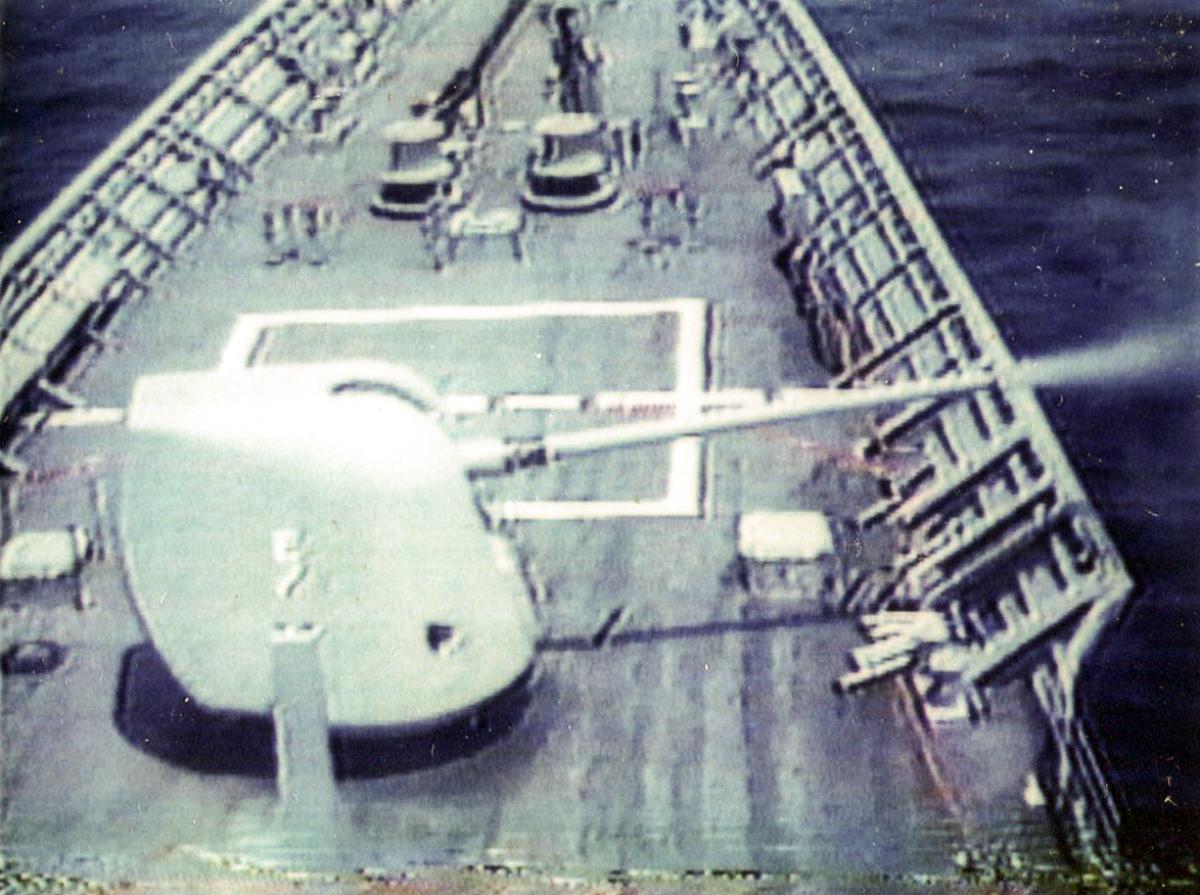

At about 0943, the Vincennes’ forward five-inch gun mount commenced to lob shells at the Iranian gunboats.14

From the videotape recorded on Vincennes’ bridge that day, the gunboats, seen as mere specks in the distance, returned fire; they did not initiate the shooting. The Iranian gunboats’ light weapons were greatly outranged by the heavier ordnance on the Vincennes, and the spent shells from the Iranians’ weapons fell harmlessly as a brief line of splashes in the water, hundreds of yards short of the Vincennes, and fully 45 seconds after the Vincennes’ first rounds were fired.15

At 0947, Captain Rezaian pushed the throttles on his Airbus to take-off thrust and began rolling down the runway at Bandar Abbas.16

On board the Sides moments later, the tactical action officer (TAO) informed Captain Carlson, “Captain, we have a contact. Vincennes designated this contact as an F-14 coming out of Bandar Abbas.” The contact was assigned track number 4131 by the Sides, and through Link-11 the Vincennes, following the same contact as track 4474, dropped that number and adopted Sides’ track number.17

Captain Carlson recalled, “I was standing between my TAO and weapons control officer. I asked, 'Do we have it?'"

"Yes, sir, we've got skin, it's a good contact," was the reply, indicating that electronic energy transmitted by the Sides' air search radar was bouncing off the plane.

"I glanced at it," said Captain Carlson, "It was around 3,000 feet, 350 knots. Nothing remarkable, so I said to the ESM [electronic support measures] talker, any ESM [emissions]?"

"No, sir. She's cold nose. Nothin' on her."

"Okay, are we talking to him?"

"Captain, we've gone out over the IAD [International Air Distress] and MAD [Military Air Distress], and so has Vincennes. We are trying every net with this guy, and so far we have no response," was the reply.

"Okay, light him up," Captain Carlson ordered. He explained that it was standard practice to illuminate Iranian military aircraft with missile fire control radar as a warning for them to turn around.

"When you put that radar on them, they went home. They were not interested in any missiles," Captain Carlson recalled.

"But this contact didn't move. I looked at the console again. More altitude. More speed. Got any ESM?" Captain Carlson asked.

"Nothing."

"And he's still not talking?"

"No, sir, we're getting nothing out of him."

"I evaluated track 4131 verbally as not a threat. My TAO gave me a quizzical look, and I explained, 'He's climbing. He's slow. I don't see any radar emissions. He's in the middle of our missile envelope, and there is no precedent for any kind of an attack by an F-14 against surface ships. So, non-threat," Captain Carlson recalled.

As Captain Carlson and his tactical action officer were evaluating an Iranian P-3's activities on the radar scope, they overheard Captain Rogers' transmission, announcing to higher headquarters his intention to shoot down track 4131 at 20 miles.

Captain Carlson was thunderstruck: "I said to the folks around me, 'Why, what the hell is he doing?' I went through the drill again. F-14. He's climbing. By now this damn thing is at about 7,000 feet. Then, I said in my mind, maybe I'm not looking at this right. You know, he's got this Aegis cruiser. He's got an intelligence team aboard. He must know something I don't know."18

On the Vincennes the picture was different. Captain Carlson knew that from Captain Rogers' perspective the presumed F-14 would pass almost directly overhead. What he did not know was that the watchstanders might also have been telling Captain Rogers the contact was diving.19

"Rogers saw it as a threat because he supposedly was being told it was diving. As I was going through the drill again in my mind, trying to figure out why I was wrong, he shot it down," Captain Carlson said.

"Then I found out that my guys back in the corner had evaluated the IFF [identification friend or foe] and had determined that it was a commercial aircraft. They were horrified."

"And this is where I take some responsibility for this mess. If I had been smarter, if I had said it doesn't smell like an F-14, and pushed for a re-evaluation, and if my guys had come forward, saying that's an IFF squawk for a haj [Islamic pilgrim] flight, I might have been stimulated to go back to Rogers and say, 'It looks like you've got COMAIR here."

"But I didn't do it, and the investigators walked away from that," Captain Carlson said.

In his book, Captain Rogers said that at 0953, just before he authorized missile firing, he again requested verification of the IFF code being broadcast by track 4131 as that of an Iranian military aircraft. "This was reaffirmed," he wrote.20

The information on the transponder emissions is unambiguous, however. According to Admiral Fogarty's report of investigation, "The data from USS Vincennes' tapes, information from USS Sides and reliable intelligence information corroborate the fact that TN 4131 was on a normal commercial air flight plan profile…squawking Mode III 6760, on a continuous ascent in altitude from take-off at Bandar Abbas to shoot down."21

The number in the 6700-series indicated it was a commercial aircraft.

Both Captain Rogers and Captain Carlson had this information.

"I told the investigators that I believed there was sufficient information, had it been processed properly, to have stopped this thing from happening. And that point is never addressed in their report," Captain Carlson said. And Captain Carlson has a theory about this curious avoidance.

"Why do they walk away? Because if you want to hang Dave Carlson, you've got to hang Will Rogers. And if you want to hang Will Rogers, then the question is going to be why was he doing this shit in the first place? That means you've got to pull the rope and hang Admiral Less for giving him permission," Captain Carlson said.

"And worse than that, you would then have to go back in front of the American people and say, 'Excuse me, folks, but the explanation you just got from Admiral Crowe, the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs, saying that this was a justifiable action, and that the Vincennes was defending herself from an attack, cannot be supported by the facts,’" Captain Carlson said.

All this, of course, would have come out if information available within days of the tragedy had been made public.

The U.S. Navy's reluctance to face weeks of scandalous media attention was matched by what we might surmise as a certain political hesitancy against full disclosure. The Vincennes affair occurred four months away from the 1988 Presidential election. Then Vice President George Bush had gone before the United Nations on 14 July and declared, "One thing is clear, and that is that USS Vincennes acted in self-defense…It occurred in the midst of a naval attack initiated by Iranian vessels against a neutral vessel and subsequently against the Vincennes when she came to the aid of the innocent ship in distress."22

As it came to pass, none of this was true.

However, the truth of the matter would have given the Democratic candidate for President, Michael Dukakis, ammunition to embarrass George Bush.

There were good reasons for spinning the story in a way that put the Iranians in the worst possible light.

Further, a court martial might have raised many ugly questions about crew training, and more questions about why Admiral Less, with one of the most important and sensitive commands in the world, was not equipped withLink 11 for real-time access to vital tactical information. Add, too, questions about command selection. And ultimately, full disclosure would have led to bedrock questions about professional ethics. For example, what is the obligation of a serving officer like Captain Carlson, an eyewitness to an event, to speak up when the facts as he sees them cast doubt on the "official" story? Indeed, what is the obligation of higher authority to own up to a mistake?

Instead, an incomplete investigation was blessed. Captain Rogers was left in command of the Vincennes and, in fact, he and key officers were rewarded with medals for their conduct. As an added fillip, all hands aboard the Vincennes and the Elmer Montgomery received combat action ribbons.

The investigation left gaping holes in at least four elements. They could be labeled the four T's—of time, tactics, truth, and television.

Time: Admiral Fogarty's investigative report and the approving endorsements dwelt at great length on the confusion and pressure of events in the five minutes precedingCaptain Rogers' order to launch missiles at the Airbus, but none of the senior leaders commented on the actions that created the time pressure. Captain Rogers had been cruising at top speed for fully 30 minutes into the fray. If he had proceeded more slowly, Captain Rogers could have purchased more time to sort out the tactical situation on the surface, and perhaps to resolve a second ambiguous track (110 miles away but descending) which he wrote later in his book was a factor in his decision to shoot.23

"We weren't leaning on our toes trying to create a problem," Captain Rogers told this writer.24 However, the course and speed records for his own ship suggest otherwise.

Tactics: By all accounts Captain Rogers' Aegis cruiser was dispatched hurriedly to the Persian Gulf to counter the threat of Iranian Silkworm antiship missiles. With its 1,100-pound warhead, a 23-foot Silkworm launched from the beach would have severely crippled or sunk any ship it hit. Aegis was the shield.

Instead of positioning his ship to best deal with the Silkworm threat, and to manage the air picture, Captain Rogers stormed into littoral waters. Moreover, he was allowed to hazard this prime asset by higher authority. Admiral Fogarty's report does not question these key matters of tactical judgment, although they are relevant to the employment of Aegis-capable ships in future coastal operations.

Truth: Admiral Fogarty's investigation accepts the testimony of console operators in the Vincennes' combat information center who said the supposed F-14 was diving. However, one officer, Lieutenant William Montford, who was standing right behind Captain Rogers and testified that he never saw indications that the aircraft was descending. At about 0951, Montford warned Captain Rogers that the contact was "possible COMAIR."25

The Aegis data tapes agree with his view. Beyond doubt, the console operators' electronic displays showed the aircraft ascending throughout. Admiral Fogarty chalked up the disparity in the statements of the majority to "scenario fulfillment" caused by "an unconscious attempt to make available evidence fit a preconceived scenario." He offered no opinion regarding the veracity of the console operators' statements.26

Admiral Fogarty's report also noted that the Iran Air Airbus took off to the southwest, although at least four people in the Vincennes'CIC testified that it took off in the other direction, toward the northeast—another major contradiction that is left unresolved.27

Captain Rogers' recollections also contain inconsistencies. Case in point: His discourse on the mysterious track 4474. Recall that the Iranian Airbus was briefly designated as 4474 by the Vincennes.

Captain Rogers claimed that a Navy A-6 flying more than 150 miles away was entered into the Naval Tactical Data System by the destroyer Spruance (DD-963) on patrol outside the Persian Gulf, using the same track number, 4474.28

According to Captain Rogers' explanation, this track was passed that morning to HMS Manchester, and through automatic exchange of data among shipboard computers the track appeared on the Vincennes' display screens at just about the same time the supposed Iranian F-14 (now track 4131) was 20 miles from the Vincennes.

The reappearance of track 4474, Captain Rogers claimed, added to the perception of an in-bound threat and contributed to his decision to shoot.

But Captain Rogers wrote in Storm Center, and Admiral Fogarty’s report confirms, that he decided before it was 20 miles away to shoot down the inbound Iranian aircraft. If track 4474 did not reappear on the screen until it was 20 miles away, then by definition track 4474 could not have been a factor pushing Captain Rogers to make his initial decision to shoot.

Television: After the engagement, the Navy camcorder crew boarded one of the Vincennes' launches to assess damage to the cruiser. The close-up views of the starboard side of the hull, where Captain Rogers told Admiral Fogarty’s investigators shrapnel or split bullets had struck the ship, are revealing.

Yes, there are dents and scrapes. Most look like the normal wear and tear that would result from the hull rubbing against objects pier-side. There are shallow craters in the steel, but at the deepest point, where one would expect that the strike of a bullet would leave bare metal, the paint is in pristine condition.29

Not shell craters. Mere dents. It appears that Admiral Fogarty displayed little interest in confirming Captain Rogers’ damage report for himself. After all, the Vincennes was tied up at Bahrain during the inquiry.30

The videotape shows more, such as the navigator on the bridge announcing to the officer of the deck that the Vincennes was crossing the 12-mile line demarcating Iran’s territorial waters en route to the open waters of the Persian Gulf after the engagement.

The totality of information now available suggests that Captain Rogers “defended” his ship into Iranian territorial waters, and when the air contact appeared, he blew the call.

What has happened since?

Captain Rogers retired in August 1991, and to this day insists, “At no time were we in Iranian territorial waters.”31 “I think it’s a problem of semantics,” he said in a 2 July 1992 appearance on the “Larry King Show” to publicize his book.32

Call it spin control. Call it a denial psychosis. Call it what you will, the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) report of December, 1988, clearly placed the Vincennes well inside Iran’s territorial waters.33

Captain David Carlson has written and spoken out publicly criticizing Captain Rogers’ account of the tragedy.

“Captain Rogers has got the whole force of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and of the United States Navy supporting him,” Captain Carlson said.

“I will be silent as soon as someone else in the Navy stands up for what really occurred,” Captain Carlson declared.

Although Carlson has not received a scintilla of support from the top echelon, he has received numerous letters from fellow officers. Some are rather illuminating, such as this extract:

“…I came in contact with Capt. Rogers while he was enrolled in the Commanders’ Tactical Training Course at Tactical Training Group, Pacific. At the time, I was the Operations Evaluation Group Representative to the staff. As such, I assisted…instructors…in the training wargames…Capt. Rogers was a difficult student. He wasn’t interested in the expertise of the instructors and had the disconcerting habit of violating the Rules of Engagement in the wargames. I was horrified, but not surprised, to learn Vincennes had mistakenly shot down an airliner,” he wrote.34

The top military officer involved in the Vincennes affair was Admiral William J. Crowe, the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs. His five-page endorsement of Admiral Fogarty’s investigation put the rap on Iran for allowing its airliner “to fly directly into the midst of a gunfight.”35

Admiral Crowe’s accusation begs the question: How could the pilot, or the air traffic controllers at Bandar Abbas, possibly have known of the surface engagement under way?

When the Newsweek magazine cover story on the Vincennes affair appeared last July, headlined “Sea of Lies,” Admiral Crowe, now retired, was called to testify before the House Armed Services Committee. Again, he placed much of the blame on the Iranians. Admiral Crowe also trashed the Newsweek story for its “slim evidence” and “patently false charges of cover-up.”36

But if not a “sea of lies,” the official story is hardly a river of truth. The full body of evidence is anything but slim. It includes Admiral Fogarty’s investigation, the separate report to ICAO, ships’ logs, dozens of interviews, and the 38-minute video recorded by the Navy camcorder crew, just to itemize some of the evidence.

Admiral Crowe conceded in his 21 July 1992 appearance before the House Armed Services Committee that the Aegis tapes pulled from the Vincennes definitely showed her crossing into Iranian territorial waters, and the time was known to the second.

Admiral Crowe declared that under the right of innocent passage the Vincennes had de facto clearance to enter Iranian waters. Innocent passage? Captain Rogers wasn’t passing anywhere. And if not innocent passage, then did he have the right under hot pursuit to pass through the 12-mile line? He was not already engaged. He was not under imminent threat. Indeed, according to the annotated supplement to the Commander’s Handbook on the Law of Naval Operations, for hot pursuit to apply the initiating waters. Neither of Admiral Crowe’s conditions apply.37

Indeed, the pursuit appears to have started at about 0916, when the Iranian boats were at least seven nautical miles away.38 Visibility was four nautical miles, at best. Sitting low in the water, looking into the haze, the boats’ crews would likely have not even been aware initially of the haze-grey cruiser bearing down on them.

Representative Larry Hopkins (R, KY), questioning Admiral Crowe, asked, “Do you find any fault…with what Captain Rogers did under the circumstances?”

Admiral Crowe answered that he did not find “malperformance of a criminal nature.”39

The subtlety of this point apparently slipped by Representative Hopkins and his colleagues, but Admiral Crowe’s remark should raise eyebrows among naval professionals. What he said, in effect, was that Captain Rogers cannot be held accountable because he was not criminally negligent. Yet under military law a commander can be held accountable for a non-criminal act—a major different from civil jurisprudence.

A retired Army colonel who attended the hearing was surprised and disappointed by Admiral Crowe’s testimony.

As part of a four-page commentary on this hearing, he wrote: “Graduate seminars of my day would mine the admiral’s words to prove our Navy is too dangerous to deploy…”

I see a sole winner in the Navy’s present struggle. It is not the nation, but the Air Force’s contractors. I shudder, not at paying for the hardware that will come, but for the piper who waits near the door,” this colonel concluded glumly.40

And this remark came from an officer who knows how vital the Navy’s role in littoral waters will be in coming years. Indeed, the latest maritime strategy document, issued 1 October and titled “…From the Sea,” redirects the Navy’s Cold War focus on open-ocean combat with a now-nonexistent Soviet fleet to “littoral or ‘near land’ areas of the world.”

The Vincennes affair is more relevant than ever as a vivid example of the kind of military-political gymnastics in which the Navy may be engaged in coming years. It is important for the Naval Service and for all Americans to look at the events that July day five years ago objectively, and to learn, especially since Iran continues to be demonized as a threat to stability in the region.41

Basic facts are still in dispute. The full text of Admiral Fogarty’s investigation merits declassification, and especially the geographic track files of the vessels and air contacts involved. Indeed, the secrecy still surrounding the Airbus shootdown only serves to conceal ethical and operational weaknesses from ourselves.

1. “Failure to Communicate,” Time, p. 30, 30 December 1988.

2. “Formal Investigation Into the Circumstances Surrounding the Downing of a Commercial Airliner by the USS Vincennes,” by Rear Admiral William M. Fogarty, USN, 28 July 1988, pp. 28, 32, and 47. Hereinafter referred to as the Fogarty Report.

3. Personal interview with Captain David Carlson of 23 June 1992 and confirmed by telephone interview with Captain Hattan 29 June 1992.

4. Storm Center, by Captain Will Rogers and Sharon Rogers, Naval Institute Press, 1992, p. 88.

5. In his July 1988 sworn statement to Admiral Fogarty’s investigation, Lieutenant Collier conceded he was in violation of the Rules of Engagement (ROE) prohibiting a closest point of approach of less than four miles and that he was in fact one-to-two miles closer. In a subsequent letter to the editor of Newsweek magazine, published 3 August 1992, Lieutenant Collier denied ever being closer than four miles to the gunboats. The conflicting statements by Lieutenant Collier and Captain Rogers, most recently on NBC’s “Unsolved Mysteries” (air date 17 February 1993), where he said he was directed to come to the aid of the Elmer Montgomery (contrary to all evidence in the Fogarty Report), are further reason for declassifying the geographic track files of the aircraft and vessels involved that day.

6. “Vincennes: New Allegations, New Denials,” by David Steigman, Navy Times, 3 August 1992.

7. Fogarty Report, p. 25.

8. Carlson interview, as confirmed by a separate telephone interview on 29 June 1992 with Commander Gary Erickson.

9 Telephone interview with Captain Will Rogers, USN (Ret.), of 29 June 1992.

10. Transcript, ABC News Nightline, “The USS Vincennes: Public War, Secret War,” air date 1 July 1992.

11. “Sea of Lies,” Newsweek, 13 July 1992, p. 31.

12. Fogarty Report, p. 25.

13. Transcript, Admiral William Crowe, USN (Ret.), testimony to House Armed Services Committee (HASC), 21 July 1992.

14. Fogarty Report, p. 25.

15. U.S. Navy videotape, as reviewed by author.

16. Fogarty Report, p. 6.

17. Carlson interview. See also Fogarty Report, pp. 30, 31, and 34. See also Storm Center, pp. 12 and 117.

18. Carlson interview.

19. Fogarty Report, pp. 35, 40, 43.

20. Storm Center, p. 16.

21. Fogarty Report, p. 8.

22. “Bush: Iran Must Share Blame in Jet Downing,” Chicago Tribune, by Timothy McNulty, 15 July 1988, pg. 1.

23. Storm Center, p. 13. According to the Fogarty Report, the range was 110 nm. In his book, Captain Rogers claims this contact was 180 miles distant.

24. Rogers interview.

25. Fogarty Report, p. 34.

26. Fogarty Report, p. 45.

27. Transcribed testimony of witnesses to Fogarty investigation.

28. Storm Center, p. 117.

29. Author assessment.

30. Fogarty Report, p. 26, “CO, USS Vincennes stated that…shrapnel and/or spent bullets impacted to starboard bow,” but the investigating team did not personally confirm Captain Rogers’ assessment, although as he indicated in his book the cruiser was anchored at Bahrain throughout the investigation.

31. Rogers interview.

32. Transcript, CNN, “Larry King Live,” air date 2 July 1992.

33. The ICAO report of December 1988 was based on navigation data provided by a team of U.S. naval officers.

34 Personal letter to then-Commander Carlson dated 10 September 1989.

35 Admiral Crowe endorsement to Fogarty Report dated 18 August 1988, p. 3.

36 Transcript, Admiral Crowe testimony to HASC, 21 July 1992.

37 Annotated Supplement to the Commander’s Handbook on the Law of Naval Operations, NWP 9 (Revision A), FMFM 1-10, 5 October 1989, Washington, D.C., Chapter 3, Section 3.9.1.

38 Fogarty Report, p. 25.

39 Transcript, Admiral Crowe testimony to HASC, 21 July 1992.

40 Colonel Carl Bernard, U.S. Army (Ret.), personal note to author dated 22 July 1992.

41 Seminar, “The Clinton Administration and the Future of U.S.-Iran Relations,” 14 January 1993, Washington Vista Hotel, sponsored by the department of Middle Eastern Studies, Rutgers University, Richard Cottam, James Bill, et. al., speakers.