For the escorts of Battle Group Foxtrot, preparations for the 18 April 1988 Operation Praying Mantis began in the southern California operating area ten months earlier. From this first underway period as a unit, the Battle Group Commander, Rear Admiral Guy Zeller (Commander Cruiser Destroyer Group Three), had insisted on a rigorous set of exercises to prepare for the upcoming tour on station in the North Arabian Sea (NAS). Initially, the ships drilled hard at interpreting rules of engagement (ROE) and at devising means to counter small high-speed surface craft (e.g., Boghammers) and low, slow-flying aircraft—both of which abound in and around the Persian Gulf. We later added exercises stressing anti-Silkworm (an Iranian surface-to-surface missile) tactics, boarding and search, Sledgehammer (a procedure to vector attack aircraft to a surface threat), convoy escort procedures, naval gunfire support (NGFS), and mine detection and destruction exercises.

We practiced in every environment-in the Bering Sea during November, throughout our transit to the Western Pacific and Indian Ocean, and on station in the NAS. During the battle group evolution off Hawaii in January, we executed a 96-hour Persian Gulf scenario, with a three submarine threat overlaid. We conducted live, coordinated Harpoon missile firings in southern California and off Hawaii, dropped Rockeye, Skipper, and laser-guided bombs (LGBs) on high-speed targets off Point Mugu and Hawaii and drilled, drilled, drilled. By late March, each ship had completed dozens of these exercises, and we were considering easing the pace and working on ways to make the exercises more interesting, as the day approached when the Forrestal (CV-59) battle group would relieve us. Such philosophic discussions ended abruptly when the USS Samuel B. Roberts (FFG-58) hit a mine on 14 April.

Four battle group ships en route to a port call in Mombasa were turned around, and the USS Joseph Strauss (DDG-16) and USS Bagley (FF-1069) raced north, refueled from the USS Wabash (AOR-5) and steamed through the Straight of Hormuz at more than 25 knots to join teammates, the USS Merrill (DD-976) and USS Lynde McCormick (DDG-8). They, and their Middle East Force (MEF) counterparts, the USS Simpson (FFG-56), USS O'Brien (DD-975), USS Jack Williams (FFG-24), USS Wainwright (CG-28), USS Gary (FFG-51), and USS Trenton (LPD-14) repositioned at high speed as the plan was developed. In the NAS, the USS Enterprise (CVN-65) closed to within 120 nautical miles of the Strait of Hormuz. Her escorts, the USS Reasoner (FF-1063) and Truxtun (CGN-35), were stationed to counter the potential small combatant threat in the Strait, and the air threat from Chah Bahar.

On 16 April, I flew with Lieutenant Commander Mark "Micro" Kosnik—my one-officer "battle micro staff"—from the Enterprise to Bahrain at the direction of Commander, Joint Task Force Middle East (CJTFME), Rear Admiral Anthony Less, to assist in planning and executing the response. We were joined on the flagship, the USS Coronado (AGF-11), by the MEF Destroyer Squadron Commander and began working on the plan with the CJTFME staff and other players. The objectives were clear:

- Sink the Iranian Saam-class frigate Sabalan or a suitable substitute.

- Neutralize the surveillance posts on the Sassan and Sirri gas/oil separation platforms (GOSPs) and the Rahkish GOSP, if sinking a ship was not practicable.

There were also a number of caveats (avoid civilian casualties and collateral damage, limit adverse environmental effects) to ensure that this was in fact a "proportional response."

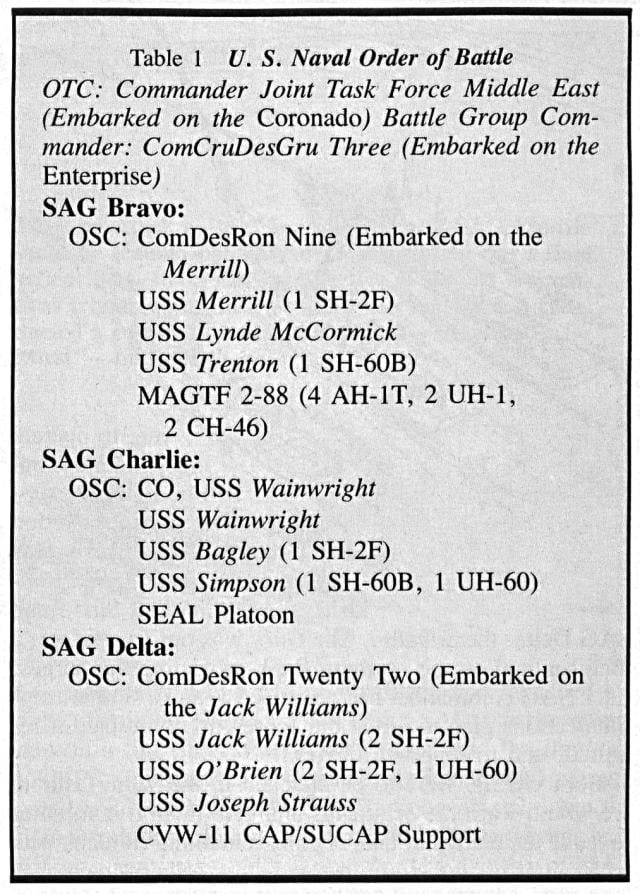

It was a long night, but by 0330 on 17 April we had developed a plan. We formed three surface action groups, each containing both battle group and MEF ships, that were to operate independently but still be mutually supportive. Surface Action Group (SAG) Bravo was assigned Sassan (and Rahkish), SAG Charlie, Sirri, and SAG Delta, the Sabalan. The Gary was our free safety, a lone sentinel on the northern flank protecting the barges. Each SAG commander had an objective and a simple communications plan to direct our forces, to coordinate if required, and to report to CJFTME.

Both GOSPs were to be attacked in the same fashion: we would warn the occupants and give them five minutes to leave the platform, take out any remaining Iranians with naval gunfire, insert a raid force (Marine reconnaissance unit at Sassan/SEALs at Sirri) on the platform, plant demolition charges, and destroy the surveillance post. Colonel Bill Rakow, Commander of Marine Air-Ground Task Force (MAGTF) 2-88, and I developed a plan to coordinate NGFS and Cobra landing zone preparatory fire and discussed criteria for committing the raid force, which included the possibilities of die-hard defenders, secondary explosions, and booby traps.

At first light, as SAG Bravo approached the Sassan GOSP, the Trenton began launching helos, including the LAMPS-III from the Samuel B. Roberts, which we used for surface surveillance. The GOSP appeared unalerted as we came into view from the southwest and turned to a northerly firing course- our gun target line was limited by a United Arab Emirates oil field three nautical miles south of Sassan and a large hydrogen sulfide tank on the northern end of the GOSP. H-Hour was set at 0800; at 0755, we warned the Sassan GOSP inhabitants in Farsi and English.

"You have five minutes to abandon the platform; I intend to destroy it at 0800."

This transmission stimulated a good deal of interest and activity among a growing group of Iranians, milling about on the roof of the living quarters. Several men manned their 23-mm. gun and trained it on the Merrill about 5,000 yards away, but many more headed for the two tugs tied up alongside the platform. One tug left almost immediately, and the other departed with about 30 men on board soon afterward. The VHF radio blared a cacophony of English and Farsi as the GOSP occupants simultaneously reported to (screamed at) naval headquarters and pleaded with us for more time. At 0804, we told the inhabitants that their time was up and commenced firing at the gun emplacement. This was not a classic NGFS mission; I had decided on airbursts over the GOSP to pin down personnel and destroy command-and-control antennae, but to avoid holing potential helo landing surfaces.

At the first muzzle flash from the Merrill's 5-inch mount 51, the Iranian 23-mm. gun mount opened up, getting the attention of the ship's bridge and topside watchstanders. The Merrill immediately silenced the Iranian gun with a direct hit, and encountered no further opposition. After about 50 rounds had exploded over the southern half of the GOSP, a large crowd of converted martyrs gathered at the northern end. At this point, we checked fire and permitted a tug to return and pick up what appeared to be the rest of the Sassan GOSP occupants. Following this exodus, the Merrill and the Lynde McCormick alternated firing airbursts over the entire GOSP (less the hydrogen sulfide tank), and we watched the platform closely for any sign of activity but saw none. As this preparatory NGFS progressed, Colonel Rakow and I selected 0925 as the time to land his raid force. Ina closely coordinated sequence, the ships checked fire, Cobra gunships delivered covering fire, and the UH-1 and CH-46 helos inserted the Marines via fast rope. It was a textbook assault, and I caught myself stopping to admire it. Despite some tense moments when Iranian ammunition stores cooked off, the platform was fully secured in about 30 minutes, and the demolition and intelligence-gathering teams flew to the GOSP. About two hours later, 1,500 pounds of plastic explosives were detonated by remote control, turning the GOSP into an inferno.

Meanwhile, the fog of war had closed in periodically. First, a United Arab Emirates patrol boat approached at high speed from the northwest. We evaluated it as a possible Boghammer—a popular classification that day. It could be engaged under the ROE, but we just identified it and asked it to remain clear. Later, we reconstituted SAG Bravo and headed north to attack Rahkish GOSP, for no ship had yet been located and sunk. A Cobra helo crew, our closest air asset, evaluated a 25-knot contact closing from the northeast as a warship. This quickly took shape as a "possible Iranian Saam FFG," and the Merrill made preparations to launch a Harpoon attack. We then asked for further descriptive information and ultimately for a hull number. The contact turned out to be a Soviet Sovremennyy-classDDG. The skipper, when asked his intention, replied with a heavy accent, "I vant to take peectures for heestory." We breathed easier. Shortly after that, SAG Bravo was instructed to proceed at full speed to the eastern Gulf, in response to Boghammer attacks in the Mubarek oil field. That ended our participation in the day's fireworks.

At the Sirri GOSP, the sequence of events began essentially the same way they did at Sassan. SAG Charlie gave warnings on time, most of the occupants departed on a tug, and the Wainwright, Bagley, and Simpson commenced fire about 0815. Sirri was an active oil-producing platform, however, and one of the initial rounds hit a compressed gas tank, setting the GOSP ablaze and incinerating the gun crew. Thus, it became unnecessary to insert the SEAL platoon.

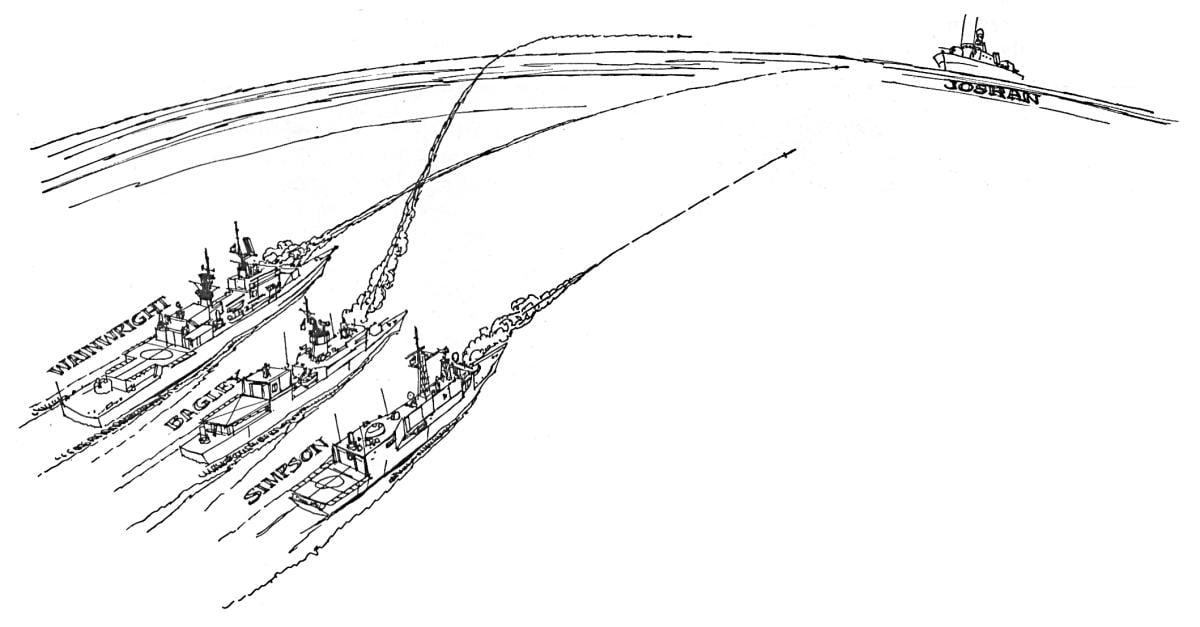

With the primary mission accomplished, SAG Charlie patrolled the area. About three hours later, they detected the approach of an Iranian Kaman patrol boat, which the Bagley's LAMPS-I identified as the Joshan. As the patrol boat closed, the SAG commander repeatedly warned the Iranian that he was standing into danger and advised him to alter course and depart the area. When his direction was ignored, the U. S. commander requested and was granted "weapons free" by CJTFME. He then advised the Joshan:

"Stop your engines and abandon ship; I intend to sink you."

After thinking this communication over, the Joshan's CO apparently decided to go out firing and launched his only remaining Harpoon. The three SAG Charlie ships, now in a line abreast at 26,000 yards, and the Bagley's LAMPS simultaneously detected the launch and maneuvered and launched chaff. The Harpoon passed down the Wainwright's starboard side close aboard (the seeker may not have activated) and was answered by a volley of SM-1 missiles from the Simpson and the Wainwright. Four missiles fired; four hits. An additional SM-1 (a hit) and a Harpoon (a miss, probably resulting from the sinking Joshan's sudden lack of freeboard) were fired, and the patrol boat was eventually sunk with gunfire.

SAG Charlie had still more opportunities to modify the Iranian naval order of battle when an F-4 made a high-speed approach just prior to the sinking of the Joshan hulk (SAG Bravo also detected approaching F-4s, but those dove to the deck and departed as they reached SM-1 range). The Wainwright is SM-2 equipped. As the F-4 continued to close, ignoring warnings on both military and internal air defense circuits, the SAG Commander fired two missiles and hit the Iranian aircraft. Only the pilot's heroic efforts enabled the Iranians to recover the badly damaged aircraft at Bandar Abbas. At this point, SAG Charlie was through for the day, as well.

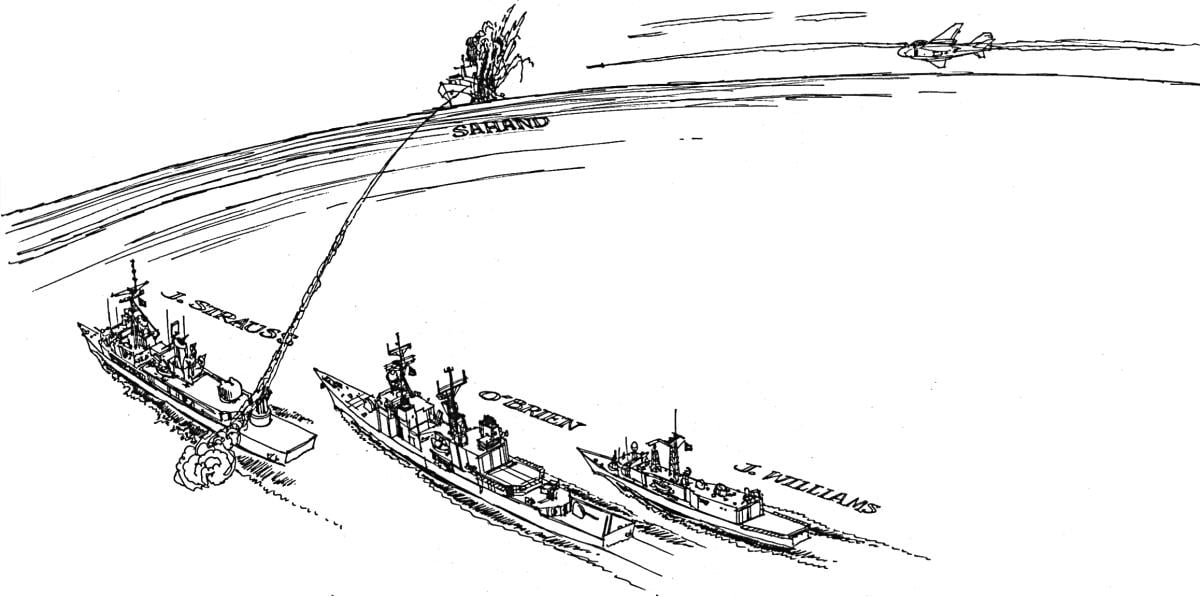

For SAG Delta, it had been a frustrating night and day of following up intelligence leads and electronic sniffs as they tried to locate the Sabalan. Various reports had held her in port or close to Bandar Abbas with engineering problems. The tempo picked up when the U. S. civilian tug Willy Tide and a U. S. oil platform were attacked by Iranian Boghammers near the Saleh and Mubarek oil fields. The Joseph Strauss provided initial vectors that assisted the A-6s in locating and destroying one of these high-speed craft and chasing the others onto the beach at Abu Musa Island. Following this successful tactical air engagement, an Iranian Saam-classfrigate, the Sahand, was discovered proceeding southwest at high speed toward the Mubarek and Suleh fields, perhaps as part of a preplanned Iranian response to the GOSP attacks. Another CVW-II A-6 detected her when it flew low for a visual identification. Pursued by antiaircraft fire, the A-6 evaded and reattacked with Harpoon, Skipper, and a laser-guided bomb. This brought the Sahand dead in the water as SAG Delta closed on the position at high speed. The Joseph Strauss conducted a coordinated Harpoon attack with the A-6's wingman, achieving near-simultaneous times on target in the first-ever coordinated Harpoon attack in combat.

Although this was the SAG's final participation in the day's attack on Iranian forces, their location in the crowded waters of the Strait of Hormuz-closest to the Bandar Abbas naval base and airfield-led to several tense moments. Reports of Iranian Silkworm antiship missile firings and the apparent presence of targeting aircraft caused the SAG to fire SM-1 missiles at suspected air contacts and in several other near engagements. Because of the concentrated efforts of both Battle Group Foxtrot and SAG Delta assets—with special credit going to the E-2C and F-14 aircrews—however, there were no blue-on-blue or blue-on-white engagements. These results reflect an extraordinary degree of discipline on the part of ship and air crews, as well as a bit of good luck, in this area jammed with so many oil platforms, neutral naval and merchant ships, small craft, and civilian aircraft.

As the sun set on 18 April, all objectives of Operation Praying Mantis had been achieved. There were no civilian or U. S. casualties, and collateral damage was nil. The Iranian war effort had been struck a decisive and devastating blow. Tactics and procedures that had been honed over the previous nine months had been dramatically validated, but a number of lessons were (re)learned which should be reviewed by commanders in future "proportional responses" of this sort. They include:

- KISS: Keep It Simple, Stupid. Simple plans, with clear objectives and a minimum of interdependence and rudder orders from higher authority are most effective.

- Force Integration: Pairing up disparate forces (e .g., at least one MEF and one battle group ship in each SAG; co-locating SAG and MAGTF commanders) is essential in a joint—or multiple task group—operation.

- Surface Surveillance: Air assets, fixed wing and helos, are essential to force protection, targeting, and battle damage assessment. Visual identification is almost always required; especially in areas with high white and blue shipping densities.

- "Proportional" responses. Classic contingency plans do not contain such options and should. The order to respond will leave little time to plan and collect intelligence.

- Linguistic support: The Farsi linguist was indispensable; both in communicating with the Iranians and in gleaning intelligence from clear radio circuits.

- GOSP destruction: This was not classic NGFS since the goal was to clear the platform, not destroy it. Their distinctive construction makes shooting off platform legs a non-starter and a waste of ammunition (we fired 208 rounds total at both Sassan and Sirri). Airbursts were effective for this mission but mechanical time fuse ammunition was in short supply.

- Warnings: Warning an armed GOSP—or worse, a warship—prior to opening fire may register high on the humane scale, but it clearly ranks low in terms of relative tactical advantage. We should rethink this requirement.

- Missile performance: SM-1 in the surface mode worked very well (five fired; five hits), which is better than my earlier experiences. With its high speed, it should be the weapon of choice in a line-of-sight engagement. Harpoon performance was good, and its use as a "stopper"—even at relatively short range and in proximity of other shipping—was validated.

- Fog of war: Karl von Clausewitz was right; it is always there. Commanding officers need to think through, talk through, and exercise in as many scenarios as possible with their watch teams. There is no cookbook solution to the problem of deciding when to shoot and when to take one more look first.

Most of us believe in the deterrent value of sea power and hope that by such strength we will successfully avoid conflict. Should deterrence fail, however, and hostilities occur, each of us wants to be there to act swiftly and decisively. Such was the opportunity presented to the ships and aircraft of Battle Group Foxtrot and the Middle East Force on 18 April 1988, and their crews did themselves, and all Americans, proud.