In combat, there are two types of aircraft: friend and foe. Rules of engagement may provide definitions of friend and foe, but the question that operators must answer is how do you actually tell the good guys from the bad guys? The increasing speed, maneuverability, and firepower of the aerial threat leave little or no margin for error in identification. For years, the burden of proof that an aircraft is friendly has rested with the aircraft itself. Failure to prove itself friendly will almost certainly result in its being evaluated as “hostile” and engaged. Thus, over the years visual techniques, prearranged flight profiles, and auto- responsive electronics systems have been developed and used by aircraft to prove that they are friendly. Even so, tactics, techniques, and technology are not foolproof; friends do get shot down from time to time.

On 3 July 1988, the guided- missile cruiser Vincennes (CG- 49) evaluated a radar contact as a hostile Iranian military aircraft. The Vincennes engaged and destroyed the contact with a pair of surface-to-air missiles (SAMs). The target proved to be a civilian airliner, Iran Air

Flight 655 en route from Bandar Abbas to Dubai; a scheduled flight in an established commercial airway. Some 290 persons from six different nations were on board; all were killed. Why was it evaluated as foe?

With the tense atmosphere that already existed in the Vincennes' s operating area before the action, coupled with the demands of the action itself, there should be no question that the Vincennes's crewmen—in particular those in the CIC who knew the most about what was occurring—were under stress. The investigating officer concluded in the formal report that “combat induced stress on personnel may have played a significant role in this incident.”1 History suggests that the investigating officer has understated this conclusion; that even the most disciplined forces are at some point in their combat experience subject to stress and its effects on their actions.

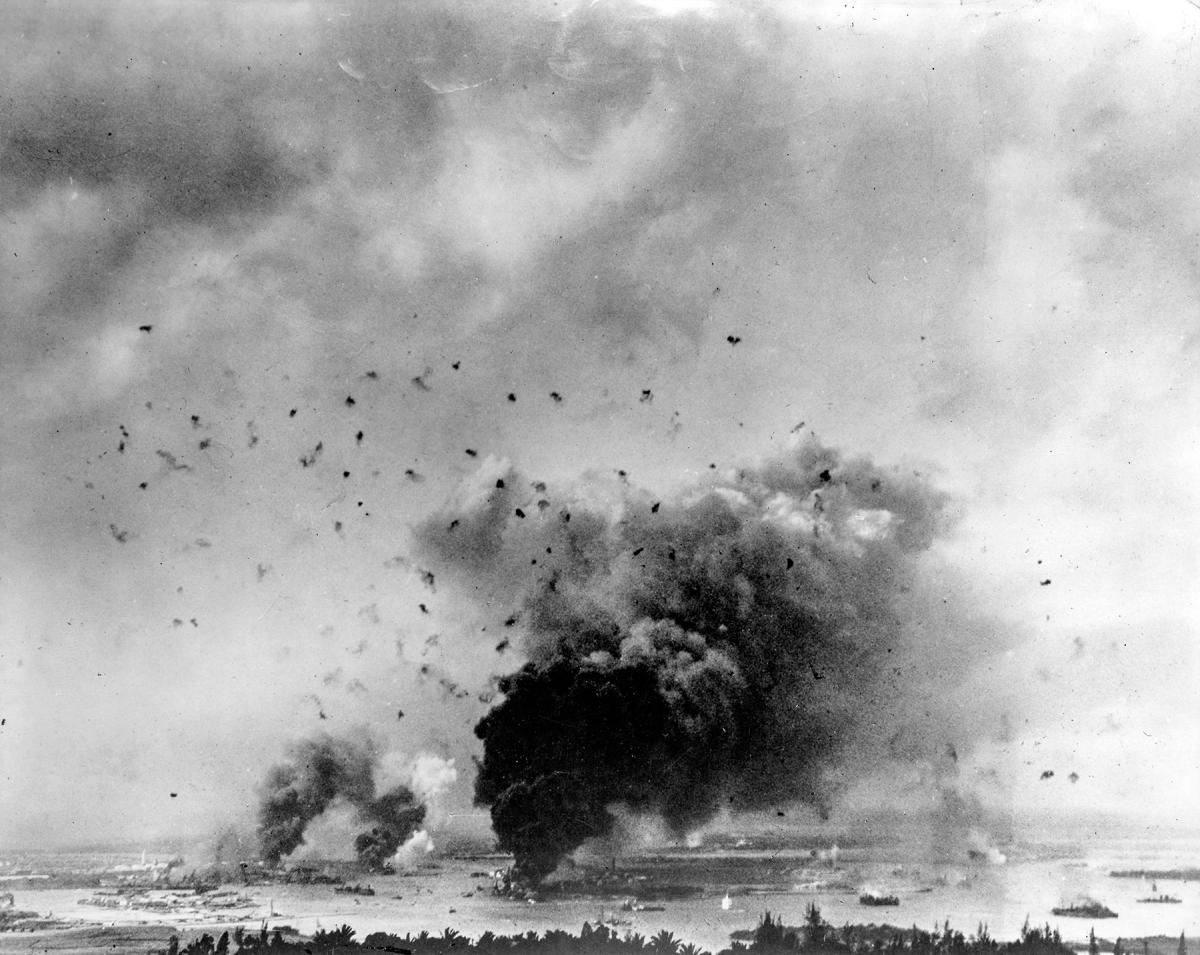

On the day that Japan bombed Pearl Harbor, a flight of 12 B-17 Flying Fortresses was scheduled to arrive in Hawaii from the continental United States. Indeed, when the Japanese attackers were first detected approaching Hawaii, they were evaluated as those B-17s making their approach to the islands.

The U. S. bombers had the misfortune to arrive over Oahu at the height of the first Japanese attack. The B-17s were immediately attacked by Japanese fighters and, even though they were visible from the ground, by U. S. antiaircraft batteries. This was the first of many friend versus friend engagements in World War II that can only be attributed to stress under fire. Such incidents—which included air- to-air, air-to-surface, surface-to- air, and surface-to-surface engagements—were not limited to that war. They occurred in the Korean and Vietnamese conflicts, as well. But one World War II engagement during the Allied invasion of Sicily in July 1943 is particularly germane to this discussion.

On the night of 11 July, after attacking U. S. ships off the Gela beachhead throughout the day, German bombers attacked the U. S. Seventh Army landing area and the supporting fleet anchorage in force, using strings of parachute flares to help them pick their targets. U. S. Navy gunners, firing heavy barrages, engaged these bombers even though they could not see their targets, which were obscured by altitude and the glare of the bombers’ flares.

Later that evening, at 2230, both the fleet and the Army antiaircraft batteries ashore detected what they believed was another inbound German raid. This time, however, the raiders were coming in low, only a few hundred feet above the water.

The exhaust flames from their engines were clearly visible to the air defenses ashore and afloat. More than 5,000 guns of various calibers opened fire, hitting a number of planes, which crashed into the beachhead and adjacent waters. The gunners, observing that some of the raiders were dropping parachute- suspended objects suspected of being antishipping mines, attempted to detonate them by gunfire while they were still in the air.

Not until one of the aircraft crashed close to a U. S. Navy destroyer was it discovered that the low flying “raiders” were, in fact, 144 U. S. C-47 transports carrying 2,000 paratroopers of the 82nd Airborne Division.

A total of 23 transports were destroyed, six before their embarked troopers could jump, and 37 were badly damaged. In the end, 229 paratroopers were killed, wounded, or missing.

This tragedy happened in spite of major, high-level attempts to ensure the safety of the transport aircraft and their embarked troops. General George S. Patton, commanding the U. S. Seventh Army, directed that all units concerned be advised when and where the airborne reinforcements would arrive. Major General Matthew Ridgway, commanding the 82nd Airborne, flew from North Africa to Sicily to ensure that Patton’s warning order had been properly disseminated. General Ridgway had previously been assured by Navy commanders that his aircraft would not be fired upon by the fleet if they flew along a specified corridor along the beachhead. This is the route they flew, displaying the proper amber recognition lights, but some units failed to get the word.

General Dwight D. Eisenhower, then-supreme allied commander noted in his post mortem comments that the route the transports were directed to fly “followed the actual battlefront for 35 miles; and the antiaircraft gunners on ship and shore had been conditioned by two days of air attacks to shoot [on] sight.2

It is likely, therefore, that the gunners would have fired at the transports even if they had received General Patton’s warning- The transports’ arrival hard on the heels of a German raid virtually guaranteed the hostile reception that they received. Under stress, the gunners saw what they expected to see.

After an investigation of the Gela disaster had been completed, General Ridgway wrote that the responsibility for it was “so divided, so difficult to fix that no disciplinary action should be taken.3 Similarly, the investigating officer of the Vincennes incident recommended that “no disciplinary or administrative action should be taken against any US naval personnel associated with this incident.”4

General Ridgway added one other thought concerning the tragedy at Gela: “[Such] losses are part of the inevitable price of war in human life.” If the commitment of armed forces to an area of conflict lasts long enough, payment will come due- Leaders, then, must weigh whether the commitment is worth the price.

1. Investigation Report: Formal Investigation into the Downing of Iran Air Flight 655 on July 1988,” Department of Defense, p. 51

2. Robert Wallace and the editors of Time-LifeBooks Inc., World War II, The Italian Campaign (Alexandria, VA: Time-Life Books, 1981), p. 26.

3. Ibid., p. 26.

4. “Investigation Report,” p. 51.