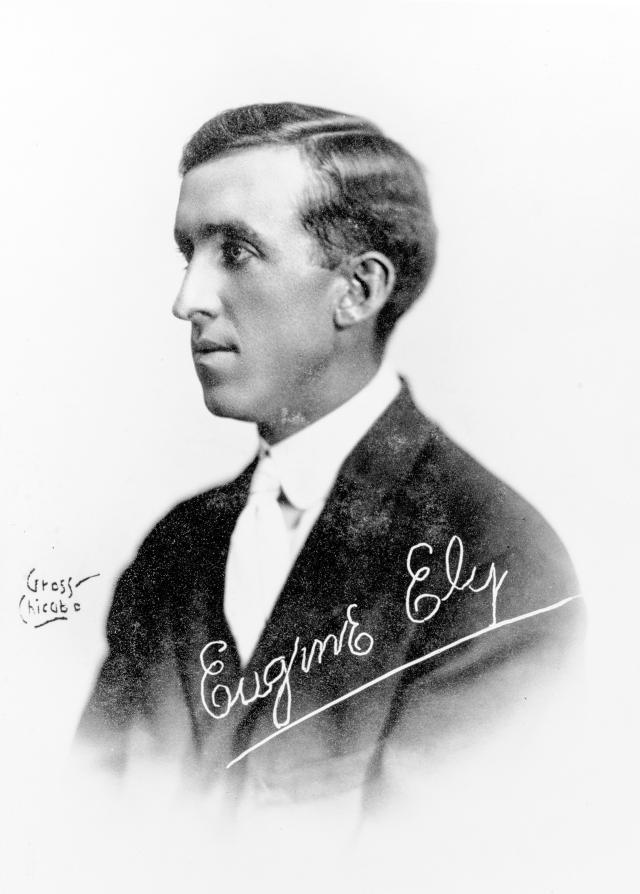

Tucked away in a corner of the Smithsonian's vast Air and Space Museum in Washington, D. C., is a small exhibit honoring Eugene B. Ely (1886–1911), the first man to land on and take off from a naval vessel. His flying career lasted only 18 months, yet he thrilled thousands and registered several solid achievements which in 1933 won him a posthumous Distinguished Flying Cross.

Ely grew up in Davenport, Iowa, attended local schools, and was graduated from Iowa State University. Mechanically inclined, he was attracted to automobiles and soon became an expert driver. Road races and work as a chauffeur took him to San Francisco where he worked for some months as an auto salesman. After marrying a local girl named Mabel Hall, he moved to Oregon.

Early in 1910, a Portland auto dealer, E. Harry Wemme, purchased a Curtiss biplane and became an agent for Curtiss products in the Northwest. Wemme, however, was afraid to fly, so Ely offered to try—and smashed the plane. Embarrassed by this turn of events, Ely bought the wreck, repaired it, and within a month had taught himself to fly. Following numerous flights in the Portland area, in June 1910 Ely set out for Canada to do exhibition work on his own. After successful appearances in Winnipeg, he moved south to Minneapolis for a flying meet which proved to be a turning point in his new career, for there he met Glenn Curtiss and several of his associates.

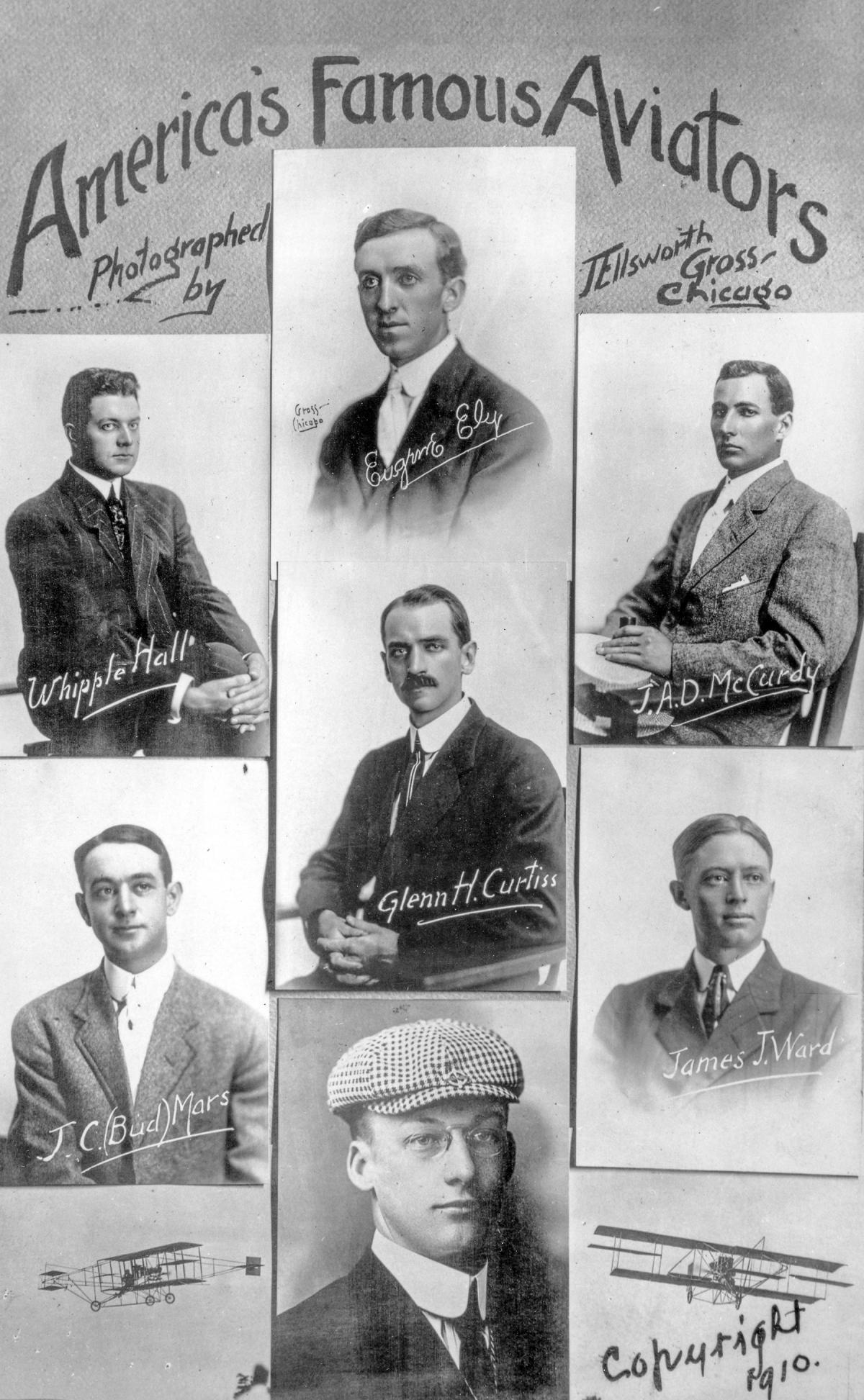

Curtiss, always on the lookout for new talent, was greatly impressed with Ely and quickly signed him on as a member of his exhibition team. As a result, in July, Ely appeared with other Curtiss flyers at Sioux City and in Omaha. He also returned to Canada for a few days and crashed while trying for the third time to fly from Winnipeg to Portage La Prairie. He recovered and accompanied the Curtiss team east to Rochester, New York, and in late August participated in a highly publicized meet held at Sheepshead Bay on Long Island where dazzled onlookers saw five planes aloft at the same time.

In September, the Curtiss team appeared at air shows in various cities in Michigan, Illinois, Virginia, and New York—all in an effort, of course, to promote Curtiss planes and to prove them superior to those being produced by rivals such as the Wright brothers. During the first week in October, Ely participated in yet another meet in Chicago. On the 5th, he received his official federal pilot's license (No. 17). Four days later, Ely set out to capture a $25,000 prize offered by The Chicago Post and The New York Times to anyone who could fly between those two cities. The first day he covered only 11 miles and the next day 20, taking him to Gary, Indiana. Discouraged by constant engine trouble, he gave up there.

This was undoubtedly a hard blow, for Eugene Ely was an ambitious young man eager to prove himself. Until he became a flier, he had been something of a drifter, unable to launch a solid career. During the next few weeks, he recouped some of his self-esteem by competing successfully with many of the biggest names in American aviation at New York's Belmont Park.

Then, in mid-November, Eugene Ely got his first big break. Two months earlier, Captain Washington Irving Chambers, often called the "father of naval aviation," had been detached from command of the battleship Louisiana and told to keep himself informed on aviation matters. Chambers was soon in contact with Curtiss and Ely, and the latter evidently offered to fly from the deck of a warship. Chambers replied that he had no money for such an experiment but agreed to provide a ship if Ely would try.

On the afternoon of 14 November—a gloomy Monday filled with low clouds, fog, and intermittent rain showers—Eugene Ely climbed into a Hudson Fulton Flyer mounted on a small platform on the deck of the scout cruiser Birmingham in Hampton Roads, Virginia. (This was the same 50-horsepower aircraft that Curtiss had piloted from Albany to New York City on 30 May 1910, a feat which won him a $10,000 prize.) The runway was 83 feet long, which meant Ely could travel only 57 feet before taking off. The five-minute flight was a success…but just barely. The plane plunged downward as soon as Ely cleared the Birmingham's bow, its wheels dipping into the water before rising. His goggles covered with spray, Ely was unable to tell where he was heading. As soon as he wiped his goggles, he saw a stretch of beach and decided to land, scrapping plans to circle the harbor and touch down at the Norfolk Navy Yard.

Although the U. S. Navy had no money for Eugene Ely, someone else did. Captain Chambers, an eyewitness to this flight and delighted with the results, immediately contacted John Barry Ryan, head of the U. S. Aeronautical Reserve. Ryan, son of financier Thomas Fortune Ryan, had offered a $500 prize to the first reservist who made a ship-to-shore flight. Although Ely was not a reservist, Chambers quickly brushed that requirement aside. He convinced Ryan to make Ely a lieutenant in the Aeronautical Reserve and award him the $500. In return, Ely presented his splintered propeller to Ryan as a memento.

Meanwhile, the Curtiss team spent the remainder of the year in the southeastern states, appearing in Norfolk, Raleigh, Columbia, Birmingham, Jackson, and New Orleans. During the Christmas holidays the fliers participated in a Los Angeles meet and then moved north to San Francisco where Eugene Ely would score his greatest triumph.

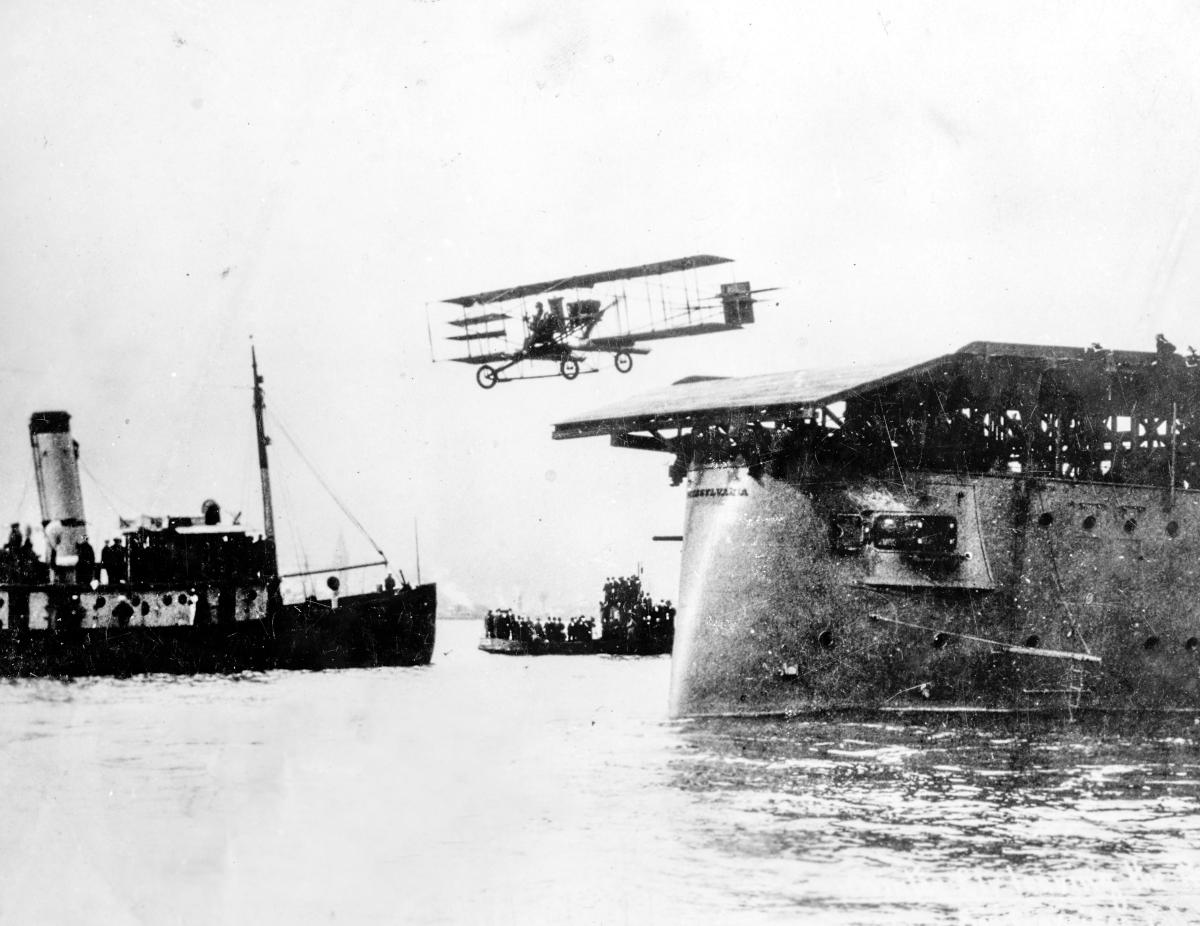

Throughout much of January 1911, the San Francisco area was caught up in a frenzy of "air" fever. Nearly every day, new records were set at the Army's Selfridge Field as planes dropped live bombs, scouted out a theoretical enemy, and received wireless messages while aloft—all for the first time in history. Yet it was Ely who stole the show. On the morning of 18 January, 70 years ago this month, he took off from Selfridge Field, flew 13 miles to a group of warships in the bay, and came to rest on a special platform (127 feet long, 32 feet wide) on the deck of the armored cruiser Pennsylvania. His Curtiss pusher, as the Air and Space Museum exhibit demonstrates, was stopped by hooks which caught ropes stretched across the platform. This mechanism, essentially the same scheme practiced today, was devised by Hugh A. Robinson, an experienced circus performer, who had used ropes in this fashion to arrest the progress of an auto in which he performed a loop-the-loop.

Ely was mobbed by scores of well-wishers and cheered by hundreds of sailors. The Pennsylvania's skipper, Captain C. F. Pond, proclaimed his feat "the most important landing of a bird since the dove flew back to the ark." (Naval experts who watched were also impressed, if less eloquent, and the following day an editorial in The San Francisco Examiner stated unabashedly: "Eugene Ely Revises World's Naval Tactics.")

An hour after his landing, Ely took off and flew back to Selfridge Field as thousands lined San Francisco Bay to watch his progress. According to the pilot's personal account, published in The Examiner on 19 January 1911, only once—as he rose above the fleet among screeching sirens—did he almost lose control of his aircraft . . . "for the first time in my life, the feeling that I had actually done a great thing came over me."

Actually, Ely seems to have treated the whole affair in a rather nonchalant fashion. Shortly after landing at Selfridge Field and just before being carried off by a mob of enthusiastic soldiers, he told a reporter, "It was easy enough. I think the trick could be successfully turned nine times out of ten."

Not everyone was impressed with what Ely had done. Aero, a British publication, printed this brief, scathing observation on 25 January 1911.

"This partakes rather too much of the nature of trick flying to be of much practical value. A naval aeroplane would be of more use if it 'landed' on the water and could then be hauled on board. A slight error in steering when trying to alight on deck would wreck the whole machine."

The papers of Captain Chambers at the Library of Congress reveal that Ely's flights for the Navy were part of a carefully calculated campaign to obtain more meaningful employment. On 30 January 1911, Ely wrote to Chambers from San Diego concerning the Navy's plans for the future.

"There will probably be an experimental station and some one who is competent will be needed to carry on the work.

"If you will let me know how to go about it, I shall try to be the one selected. Mr. Curtiss has proved that an aeroplane can rise from the water and we knew before that on[e] could alight without trouble. I have proved that a machine can leave a ship and return to it, and others have proved that an aeroplane can remain in the air for a long time, so I guess the value [of] the aeroplane for the Navy is unquestioned.

"Let me hear from you soon and oblige,

Yours Sincerely

Eugene"

Ten days later, Chambers replied, congratulating Ely on his spectacular success in San Francisco but expressing his regret that no specific job was available. The captain said he expected that the Secretary of the Navy would soon assign planes and spare parts to certain ships, just as he now apportioned boats, anchors, etc. This was preferable, Chambers cautioned, to getting a congressional appropriation which would encourage lobbyists to force their "crank" machines onto the Navy. He conceded that in a year or so experimental flying stations might be established at Annapolis, Charleston, and San Diego, and "you may rest assured that we will keep you in mind."

In a somewhat different vein, Captain Chambers added this word of caution:

"I understand you made some very risky flights out there at San Diego and I want to give you the advice of a friend to cut out the sensational features. I don't want to hear of you meeting the fate of those other fine fellows, Johnstone, Hoxsey and Moisant.

"Please remember me most cordially to Mrs. Ely and say that I expect her to continue keeping her eye on you for our sake and for the sake of aviation."

A few weeks later, Ely's father wrote to the Secretary of the Navy, also seeking a position for his son: "I am very anxious to connect him, if possible, in some way with the navy or army in his line of business." The reply he received from the Assistant Secretary expressed keen admiration for his son's work, but no job was available.

Ely spent the next five months at various meets and exhibitions throughout the West. He took time out to help train a squad of California National Guardsmen interested in aviation and to assemble a new military plane Curtiss was delivering to the U. S. Army at Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio. During these weeks, all very profitable to both the Curtiss organization and Ely, the young airman raced with autos and motorcycles and circled Oregon's capitol dome (the first man to do so). Ely's most memorable appearance, however, was at Reno on 4 July. Some 35,000 people—the governor, Indian chiefs, cowboys, miners, and skeptical old-timers—turned out to marvel at his exploits.

In August, Ely entered a $5,000 race between Gimbel's stores in New York and Philadelphia, but was forced down in New Brunswick, New Jersey, by a clogged fuel line. Following more appearances through the Northeast, during which time he first began to carry passengers, early in October he traveled home to Davenport to perform before friends and neighbors. According to The Des Moines Register, young Ely had already accumulated "a comfortable fortune"; but, when asked about retiring, he replied philosophically, "I guess I will be like the rest of them, keep at it until I am killed."

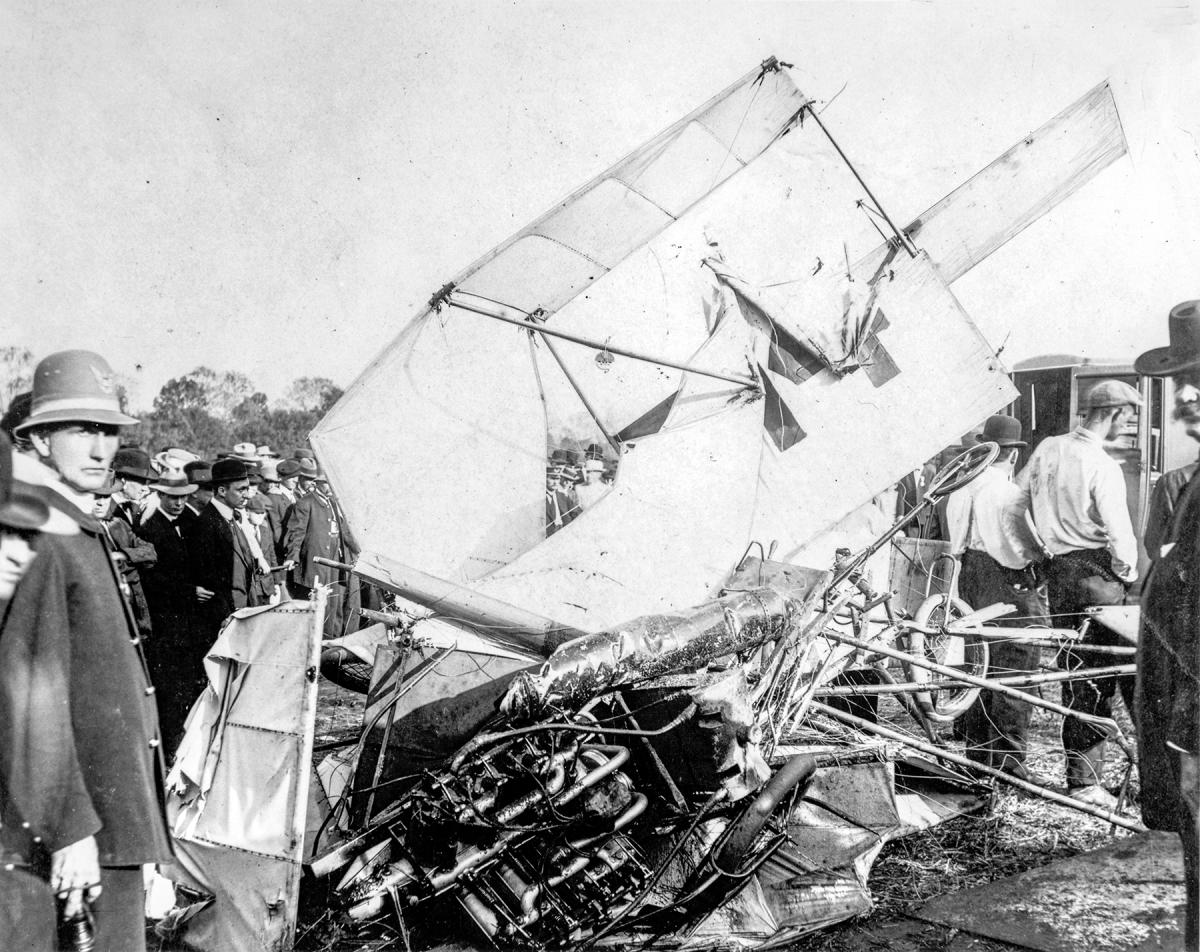

On 19 October, before 8,000 delighted spectators at the Georgia State Fair Grounds in Macon, Ely plunged his plane toward the earth. But, instead of leveling off and coming out of the dive, the craft continued downward. Ely was able to jump clear, but his neck was broken, and he died a few minutes later. As he himself had predicted, he "kept at it" until he was killed. Yet by contemporary standards, Eugene Ely was no reckless, daredevil barnstormer. He was a careful, conscientious flyer who, unfortunately, on this occasion simply misjudged his distance from the ground. According to The New York Times, this was the 101st recorded death in aviation history, a list which began in 1908 when Army Lieutenant Thomas E. Selfridge (for whom San Francisco's Selfridge Field was named) was killed at Fort Myer, Virginia, while flying with Orville Wright. Four Europeans died in 1909, 32 people in 1910, and 99 in 1911.

There is in this tale a note of sadness, not just because Eugene Ely's life was so short, but because he obviously was a very intelligent individual who could have contributed much more than he did to early aviation.

It is quite clear that Eugene Ely was eager to quit the merry-go-round of noisy crowds, hotel rooms, long train rides, and risky flights. A year of cheering and adulation was enough. He wanted to settle down and do some serious research concerning the future of aviation. But in America in 1911, that was impossible since neither private nor public money was much interested in flying machines. The French government was spending $240,000 a year on aviation competition, the Russians were contributing $100,000 to underwrite an air tour, and more than $1 million in prize money was being offered at various European meets of one sort or another. As The New York Times observed on 1 June of that year, America was "apathetic" toward aviation. At that time, by country of license, France far outdistanced all nations in air activity, having 339 registered pilots. Other countries followed in this order: Germany 43, England 39, United States 18. In short, since the United States government had no money for aviation and the public generally still thought air travel much too dangerous, the only way Eugene Ely could continue to fly was as a member of the Curtiss exhibition team, thrilling gawking throngs in town after town as he looped and dove toward the ground. His final dive, if this account from the 28 October issue of Aero is accurate, ended on an especially bitter note.

"The crowd was uncontrolled and fought about his machine for several minutes after the fall. During the struggle Ely's tie, cap, and other articles of clothing disappeared."

The man who pioneered flattop aviation deserved better than that, much better.

Data on Ely are very limited. Among the best sources are an unpublished, four-page biography filed with five scrapbooks of photos in the Photographic Section of the Naval Historical Center, Washington Navy Yard, Washington, D. C., issues of The New York Times and The Des Moines Register (1910–1911), and copies of various early aviation publications such as Aero of Sr. Louis.

See Air Scout (December 1910) for a thorough account of Ely's flight off the Birmingham. A copy of the article can be found in the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics (AIAA) Papers, Library of Congress, Box 27.

The first five pages of The San Francisco Examiner (19 January 1911) were devoted to stories and pictures of Ely's historic flight from the Pennsylvania. Ely's personal impressions were reprinted in the Marine News (October 1933). A copy of this reprint can also be found in the AIAA Papers, Box 27.