I

The Development of the Radio Telegraph

The first man to send a message through the air without wires was Sir Thomas Preece, in 1885. Making use of the inductive properties of an electric current, Preece and a friend set up two long parallel wires in a pasture. When an interrupted current was introduced in one wire, the other wire, a thousand yards away, reacted in a similar manner. What happened was that as the current passed through one wire, it threw out an electric field, which, traveling through the air to the other wire, produced an action in the second wire similar to that which had started the field in the first wire.

As the years passed, Preece improved his apparatus. In the 1890’s he was able to transmit speech across Loch Ness (1¼ miles) through his parallel wires. The great difficulty with Preece’s “wireless” was that it required such space. The parallel wires each had to be greater than the distance to be spanned, and were consequently unwieldy to handle.

Two years after Preece’s first successful transmission, Heinrich Hertz proved the theory of the mathematician Maxwell: that oscillation of a body containing current would set up an electric field similar to that set up by Preece’s long wires. Hertz proved this in the laboratory, transmitting the field a few feet, through the use of two similar balls. It remained for a young Italian, Guglielmo Marconi, to make practical use of the discovery. In 1894, on his father’s estate in Italy, Marconi succeeded in making a transmission, using the earth as one of his poles and an antenna as the other. Once Marconi had started, he expanded his operations with all possible speed. Applying immediately for a British patent, he carried his experiments to England, where by 1895 he had reached the distance of a mile, and by 1899 had sent messages across the Channel. Marconi quickly formed a company, which in ensuing years threatened to get a strangle hold on the radio industry. By 1901 Marconi had further improved his equipment, so that on December 12th, as he sat in a little room in Newfoundland, he heard faintly through the earphones three dots—S in Morse code—sent by an assistant in England! Wireless had crossed the Atlantic.

Marconi was not the only inventor in the field. France had Ducretet, England Lodge, Germany Professors Slaby and Arco, Russia Colonel Popoff, and in the United States were De Forest and Fessenden. But Marconi added business sense to his inventiveness, and, aided by the best equipment available, set out to set up his world monopoly. Probably his greatest rival was the Slaby-Arco Telefunken system sponsored by Germany, which had provided 641 of the 1550 sets in use by 1907.

From the hands of Marconi, the inventive lead passed across the Atlantic as the years went by. In 1906 De Forest invented the audion, which greatly improved transmission. In the same year, on Christmas Eve, the lonely shipboard wireless operators were astounded to hear through their earphones strains of music, and a voice raised in a wavering song. Radio-telephony had been put on the air by Fessenden. However, by the opening of the World War, this stage of radio was still comparatively in its infancy, while the code portion of radio, the radiotelegraph, had seen trans-Atlantic commercial service in October, 1907, and trans-Pacific one month after the war began.

One great practical use of radio in peacetime has been on merchant ships. Before 1900 the British Government had equipped one of their lightships with the new wireless for experimental purposes. Only a few weeks after the installation, the lightship was rammed, but the crew was saved by help from shore, summoned by the new invention. Wireless was quickly adopted throughout the world; by 1910 some 1500 merchant ships were equipped, and during the three years 1909–1911 “the passengers on no fewer than twenty-two shipwrecked vessels . . . owed their lives to the fact that the ships were equipped with a wireless telegraph system, and were consequently able to send out messages for assistance.” In 1906 an international convention was held in Berlin to discuss the question of wireless, and it was here that the call SOS was chosen as the international distress signal, not for any particular meaning, but because of the distinctiveness of the letters in Morse code. (... --- ...) In 1910, the United States passed what appears to be the first national law relating to wireless, when it was ordered that no American or foreign ship carrying fifty or more passengers might sail from a United States port (including the Great Lakes) unless such ship carried radio equipment capable of reaching 100 miles, and at least two operators (or one operator and a member of the crew capable of understanding distress calls).

Another use of radio commenced in 1904, when the Cunard Line issued the first shipboard newspaper, and travelers were thereafter able to carry on their business, even though in mid-ocean. Likewise, as freighters became equipped with radio, it was possible for the head office to order the lowly tramp to a more profitable point of call, even after the ship had left port. The privileges of the captain declined, as he became subject to orders from the air.

II

Radio in Battle

Naval strategy and tactics were changed through Marconi’s invention. While tactics were changed in certain respects, the effect on strategy appears to have been more important.

The introduction of wireless into the world’s navies gave to headquarters what they had always missed: control of the fleet at sea. The possibility of directing the fleet in ticklish situations from national headquarters appealed to the high commands of all navies, and led to the establishment of chains of high-power radio stations by all the great powers. The headquarters of the American chain was the station at Arlington, Virginia, and in advocating this station the Navy said,

The great advantage of such an installation is difficult to overestimate, for with the fleet in reach of the national capital in all parts of the Atlantic Ocean and Caribbean Sea, a much closer and more perfect surveillance may be maintained over matters of international import than has heretofore been possible.

The Navy evidently had in mind such an incident as later happened at Vera Cruz in 1914, when the admiral on the spot declined to contact the Navy Department before occupying the city. As has been said:

Approval of wireless was not yet quite unanimous; there were Admirals and Captains who were unalterably opposed to it, who believed that when a ship was out of sight of land she belonged in the hands of her master, and that orders from the blue were an outrage and an affront to dignity.

In battle, the radio can be a blessing to the admiral. Not only will it enable him to keep better control of his ships than would be possible with semaphore and flag systems, but his direct touch with headquarters will give him access to information which might affect his actions.

The greatest use of radio in warfare has probably been in the field of scouting, and it was so recognized even before World War I. With wireless the scouting force may be flung far over the horizon, where it can pick up information which may be quickly sent back to the main force. This was demonstrated as early as 1900, when scouts of the “B” fleet of the British naval maneuvers were able without delay to notify their commander of the presence of the enemy fifty miles away. The battle of Tsushima, in the Russo-Japanese War, demonstrated this fact for every one to see. The weather was very foggy; the visiblity but five miles. As the fog lifted for a moment, a Japanese scout cruiser found itself practically in the middle of the Russian fleet. It immediately informed the Japanese fleet, all of which received the message, though some units were 150 miles away. Togo immediately dispatched more scouts, who were able to keep him informed by radio of the position of the Russians at five minute intervals. Togo made his dispositions accordingly, and went into battle where and when he desired. “It was through wireless communication alone that it was possible for the Japanese commander to maneuver and place his fleet to enable him to strike the enemy in the most favorable position and under the most advantageous circumstances.” Why the Russians fell into the trap is still unknown, since it was later found that they were in possession of the latest radio equipment; they claimed they heard the messages, but from their brevity thought they were but greetings.

While wireless might prove useful in aiding landing parties in an amphibious operation, it had the disadvantage of enabling the defenders to summon aid more easily from their own forces. Likewise it was felt that supplying ships at sea might be more difficult if it was possible for scouting vessels of the enemy to inform their fleet of the operations. This fact, said Mahan, might require land bases, which would, in themselves, indicate the line of operations.

The great disadvantage in the use of radio, which is still a handicap today, was that its use alone might reveal one’s presence and position to the enemy. Not only may such codes as are used be cracked, but the very presence of wireless messages in the air will enable the enemy to guess that something is happening. By the time World War I broke, radio-direction-finders were coming into existence, which would enable the enemy to pinpoint one’s forces. In addition there is the danger that one’s forces may be spotted by ships of a neutral power, and such information sent over the air to such enemy forces as are in the vicinity. (This, in fact, happened during World War II, when American ships notified the world in general every time they saw a German submarine.)

A great difficulty in the early days of radio was that any time one sent a message over the air, practically any one with a set could pick it up. In the early days, with the spark system and the primitive receivers, there was no selectivity of stations; one could not tune in KDKA or WNBC, to the exclusion of all others. As the years passed, experiments were made in order to eliminate this difficulty; frequency variation was attempted, with some success; but as late as 1914 the equipment in use emitted a signal many kilocycles wide, one signal covering perhaps the whole of the present broadcast band. The Japanese had in 1914, and for many years previously, their own system of “Kaingunsho” of which the details were completely secret. This system enabled “the fleet to preserve absolute secrecy as to position and message;” and the Navy claimed that they used this system in the war with Russia, in particular in the battle of Tsushima. If this is true, we may have an explanation of why the Russians never acted upon hearing the Japanese wireless messages.

R. N. Vyvyan, Marconi’s chief engineer, has summarized the effect of radio on naval warfare by 1914 as follows:

Wireless telegraph had become the eyes and ears of the fleet at sea, and the days of independent action had definitely passed, where an Admiral had to rely on his own judgement as to his operations, and on such information as his fast cruisers could attain with regard to the enemy’s movements or possible intentions. By the time the Great War broke out wireless had completely changed both the strategy and tactics of war at sea. Every fleet was in direct touch with the Admiralty, and every ship in every fleet in direct contact with each other. Concerted action could be taken by different fleets or squadrons out of sight of each other, and the direction of ships, friendly or hostile, could be ascertained.

III

The Race for High Power

As wireless thrust itself upon the international scene, and military and naval writers saw its potentialities in war, governments became increasingly interested in this new method of communication. Radio grew to manhood with giant strides, through the medium, in general, of private companies. The greatest of these companies was Marconi, with control of the most effective patents, and exclusive manufacture of the best equipment. The international cable lines were already in the hands of British companies, and foreign powers saw a method of escaping from this control of their international communications. Marconi, however, had incorporated in Britain, and it appeared that perhaps this new means of communication would also be British controlled. For this reason, more than any other, I believe, other nations entered the race for radio equipment by the method of backing their own companies. Notable in this was Germany, but the other European nations were not far behind. Not until after the World War did the United States follow their lead.

As has been said, Marconi had the best equipment, and secured many contracts with navies of the world. These contracts were restrictive to a great degree, since Marconi would only lease, not sell, his sets. In addition he required a stated sum per set, an annual royalty, and restrictions upon the use of the equipment such that no set could be used for communication with the sets of another manufacturer except in cases of emergency, or in conversing with another warship. Despite these restrictions, the Royal Navy and several others equipped themselves with Marconi apparatus. One large exception was the United States, which refused to deal with Marconi except on the basis of competitive bids and outright sale.

Marconi was not interested in selling to any navy except on his own terms; so the United States went elsewhere for its equipment. This was one large cause of the establishment of the Radio Corporation of America. After the World War, the best method of transmission was by use of the Alexanderson alternator. Marconi attempted to make a deal with General Electric, who had control of the patents of this machine, whereby Marconi would have exclusive use of the alternator for communications in the United States. The Navy got wind of the deal, and communicated the details to President Wilson, who was in Paris. Wilson saw the value of having the United States in the lead in radio and persuaded General Electric to throw over Marconi and set up their own subsidiary. This subsidiary was RCA, which soon gained control of the American radio industry and eliminated Marconi from the American field.

In addition to the sale of radio equipment, Marconi went into the operation of radio communications, both domestic and international. Spanning the Atlantic, he opened commercial trans-oceanic radio service in 1909, in an attempt to cut into the cable business. In the same year he sold his British domestic business to the Post Office, which at the same time bought out Lloyds, thus keeping control of the competition of the inland telegraph lines.

During the same period plans were going forward for the institution of a commercial line across the Pacific, but various governments raised objections, and the plans were dropped. These objections were made because they interfered with the plans of the great governments who were beginning to fondle the idea of great state-controlled world-wide networks. The leaders in this movement were Germany, the United States, and the British Empire.

Various forces in all countries had been working towards such international chains for several years. The British were, in 1906, in favor of helping the commercial companies to extend their operations both on land and sea in order to have a large supply of wireless equipped vessels for use in wartime, with the necessary land stations to support them. At the same time the Admiralty was quietly building up a chain of stations down through the Mediterranean, with high-power transmitters at Gibraltar and Malta.

The American Navy since 1902 had advocated regulatory laws for radio, so that in wartime there would be a method of control of all stations, and there would be a possibility of eliminating the foreign staffs and control of the wireless companies which were invading America.

As far as I have been able to determine, there were no particular restrictions in Germany. However, the Slaby-Arco apparatus which was in general use in that country was almost on a par with the Marconi gear, and it appears that no foreign companies had any opportunity to establish a foothold in the Reich. Events proved that the Germans were not asleep.

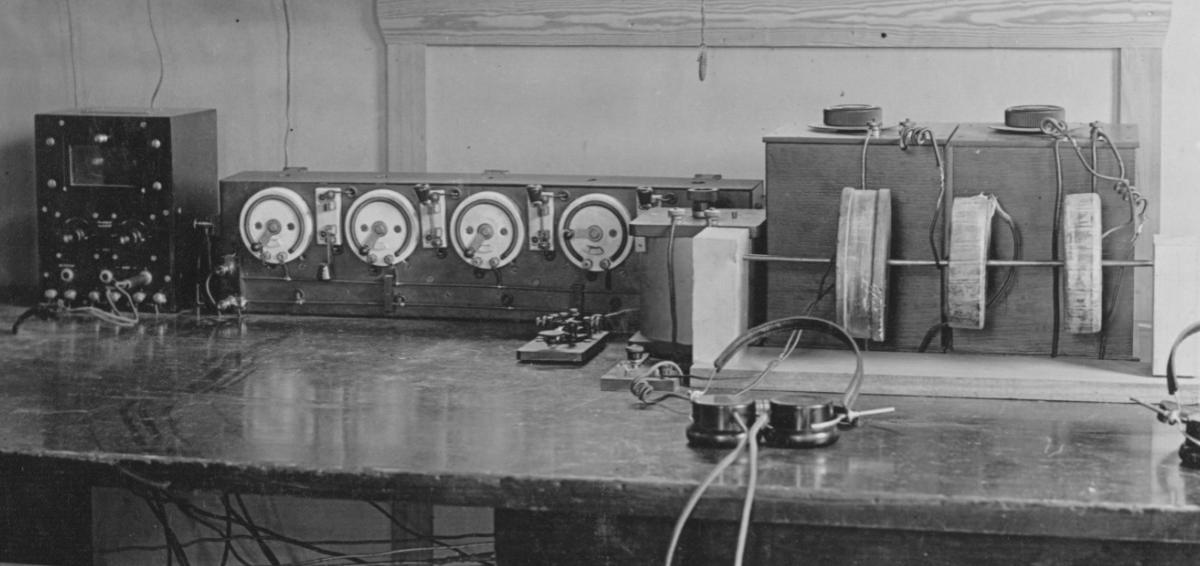

The United States Navy started early to build up chains of radio stations along the Atlantic and Pacific coasts, and in the Caribbean. However, in 1911 it was decided to construct a very high-power station at Arlington, Virginia, right outside of Washington. This station, completed by mid-1912, was the most powerful station in the world. With three towers, one of 600 feet, and the others of 450 feet, it was equipped with a 100 kilowatt spark transmitter of the Fessenden variety and had a range of 3000 miles. In addition to communication with the fleet, the station also broadcast time signals and weather information to ships at sea. During 1913 the Navy, in conjunction with the French Navy, made measurements as to the speed of radio waves and the differences of longitude between Arlington and the Eiffel Tower.

The Arlington station, built at a cost of some $200,000, was but the first of a chain to be built by the Navy. In August of 1912, Congress authorized $400,000 as a beginning appropriation towards the construction of six more high-power stations, to be built in the Canal Zone, on the California coast, Hawaii, Samoa, Guam, and the Philippines. With this chain, no ship of the Navy would be out of touch with Washington unless it were in the Arctic, Antarctic, or Indian Oceans. The chain would, to quote the Secretary of the Navy, “render our fleet independent, to a great extent, of cable lines, and will be an asset of the highest importance in time of war.”

When the war broke out, the Darien station in the Canal Zone was nearing completion, and the station at San Diego was under construction. There were also low-power stations at Honolulu and Cavite. Guam and Samoa had been struck off the list, due to the introduction of the arc transmitter, which occurred when tests at Arlington proved that better results were obtained with an arc machine one-third the size of the 100 kilowatt spark.

The high-power chain was but the main link in the Navy’s communications system. In 1904, President Roosevelt ordered all government stations on the coast to be placed under the Navy Department, and by 1908 there was intra communication up and down each coast. In addition, by extending a chain of ships across the Caribbean to Panama and thence across the Pacific, it was possible to control from Washington the entire Pacific Fleet, including the Asiatic Squadron, by 1907.

As I have said, the British were interested quite early in maintaining their control of the world’s communications. As long as they were able to control communications, in addition to their control of bunkerage, the Royal Navy was supreme. With the introduction of oil, they lost the bunkerage; radio cost them the control of communications.

In 1906 a committee of the House of Commons said,

One essential consideration from the imperial point of view is that as many as possible of the shore stations of the world should be on British territory, and therefore able to be brought in times of emergency under the control of the British Government.

In line with this policy, and with its own interests, the Admiralty from 1908 on spread a slowly increasing chain of high-power stations out from London. One hundred kilowatt stations were established at Portsmouth, Horsea, Cleethorpes, Gibraltar and Malta, with a control station at Whitehall itself.

In 1912 the Government signed a contract with the Marconi company for the construction of a chain of high-power stations which started at London and ran to Singapore, with eventual connections into Australia and New Zealand. The plan further included the tying-in of all Marconi stations in Canada. The contract as signed specified immediate construction at London, Egypt, Aden, Bangalore, Singapore, and Pretoria, for which the Marconi company would receive £60,000 per station, exclusive of cost of sites and buildings, and 10% of the gross traffic receipts for 28 years.

It was necessary for parliament to ratify this contract, and there was long delay in so doing. Some questioned the propriety of permitting a private company to do the work; others protested that the contract would be a strategic gift to aliens, enabling them to build and man the proposed installations.

The Admiralty was most unhappy about this delay. Churchill in the statement on the Navy Estimates in 1913 said that the procrastination had cost the nation dearly, not only in the gaining of a desirable wavelength but in other matters. The defenders of the contract finally won, but not until the 8th of August, 1913, a year before the war broke out. The original plan had called for the completion of the contract in twelve months, but by the time hostilities commenced, only the masts had been constructed in three of the seven stations. Britain was left without her international system of radio.

Without fanfare the Germans began the construction of their international system in 1909. In that year they opened a high-power station at Yap, a tiny island in the Pacific connected by cable to Shanghai, Guam, and Menado (Dutch East Indies). In the following years stations were opened at Rabaul, Nauru in the Marshalls, and Apia in Samoa. In addition they installed a station at Tsingtau (Kiachow) in China. All these stations were in touch with one another, although the distances between averaged some 3000 kilometers. Yap appears to have been an extremely powerful station, as in November, 1913, the cruiser Nurnberg was able to receive its messages at a distance of 6600 miles.

On the other side of the world, the Germans were equally busy. At Nauen in Germany they constructed, in 1912, an extremely powerful station with a 650 foot tower. At the same time they scattered stations throughout their colonies in Africa. In Togoland, at Kamina, they built a station which stayed in continuous touch with Monrovia, Liberia, where three cables from South America came to shore.* Other stations were erected at Windhuk (German South West Africa), in German East Africa, and in Kamerun. Nauen was in continuous contact with Togoland, and often with Windhuk (4500 nautical miles).

In the United States, the Telefunken Company, the German agent, built a powerful station at Sayville on Long Island, which was used by them to good advantage until the United States entered the war.

The Germans had an excellent reason for building this world-wide chain. They knew that as soon as war was declared, the British would cut all the cables, which is precisely what happened. This would have left Germany completely isolated from the rest of the world telegraphically and would have seriously hampered her operations abroad. So while the British fought with the Marconi Company, and the construction of the Imperial Chain was delayed by a year, Germany quietly built up its chain. The Germans paid about three times as much as the British, and offered a better subsidy, but when the war broke, the Germans were ready. They had their trained staffs strategically spotted in neutral countries, and some six hours before war was declared, orders went out over the German network for all German ships to get into a neutral port at full speed. Thus Germany saved her shipping from the Royal Navy.

IV

Radio at War

In the years before the World War, radio had tests in certain other conflicts which took place around the globe. In its first use, in naval warfare, wireless helped the Royal Navy’s blockade of Delagoa Bay during the Boer War, where it enabled cooperative action though the ships were out of sight of each other.

It was in the Russo-Japanese War that wireless entered the naval scene as a full fledged weapon. The role of radio in the battle of Tsushima has already been told. Mahan comments upon this as follows:

. . . Togo could await Rozhestvensky where he did, at anchor, because wireless assured him of the shorter line in order to reach the point of interception. Could he have known of the enemy’s approach only through a scouting system which, though itself equally good, was dependent upon flags or lights for transmitting information, he might have had to keep nearer the line of the enemy’s route, at the probable disadvantage of remaining at sea. This does not affect the well-recognized, ancient, strategic principle of the value of interior lines, but it does seriously modify its application.

A problem of an entirely different sort also arose in this war—the problem of how to handle war correspondents equipped with wireless. The naval scene was overrun with representatives of the presses of the world— American, British, French, German, and others. In addition there were naval forces in the vicinity who had their own systems, the Russians with main stations at Port Arthur, Chifu, and on the Kwantung peninsula, and Japan with her main station in Korea. And remember that this was in the days before the great selectivity of the present day, in the days when practically anyone within range could read one’s signals throughout the band.

The New York Times and London Times had rented the dispatch boat Haimun, which they fitted up with wireless equipment of the De Forest make in communication with a shore station at Wei-Hai-Wei. The correspondent for the London paper has told his story, and it appears that for some time he roamed about the battlefields, picking up information here and there, and sending it by radio to Wei-Hai-Wei, where it was cabled to London. He made a practice of following the Japanese fleet, sending information out every time they attempted to block a channel, get into battle, and what not.

As might be supposed, such actions led to official displeasure. The Russians were perhaps the most violent. At one point one of their warships halted the Haimun for questioning by a shot across the bows. It appears that the radio operator aboard the Haimun immediately contacted Wei-Hai- Wei, asking them to notify the British fleet, which was anchored there. This was promptly done; the British commenced to get up steam; the Russian evidently was equipped with radio; it overheard the conversation between the Haimun and Wei-Hai-Wei; it left immediately in the opposite direction.

According to James of the Times, the Japanese were the cause of the cessation of the Haimun’s activities, for “the Japanese naval and military authorities recognized that the existence of a possible channel of leakage of military secrets presented a flaw in their plan of campaign.” They put such strict restrictions on the boat’s operations that it was no longer profitable to maintain the vessel.

It remained for the Russians to stir up the really great controversy. Early in the war Alexieff, commanding in the Far East, issued the following statement:

In a case in which neutral steamers having on board correspondents who might communicate war news to the enemy by means of perfected apparatus not being yet foreseen by existing conventions would be arrested near the coast of Kwantung or in the zone of operations of the Russian fleet, the correspondents will be looked upon as spies, and the steamers furnished with wireless telegraphy seized as prizes of war.

This proclamation appears never to have been enforced, but it stirred up much controversy in Europe and the United States, the majority of it in ill-will toward the Russians. The wording of this proclamation is probably the reason the Royal Navy got up steam so fast when the Haimun was stopped by the Russians. James never mentions the Russians; he says that the Haimun just kept away from them, as they were inclined to be unpleasant.

The result of all this unpleasantness about correspondents is that the press now gets carefully prepared releases, or, if lucky, some member is allowed to accompany the naval vessel into battle. But the days of correspondents’ dispatch boat are probably history.

In 1912 war broke out in the Balkans, and, while neither side was well equipped with wireless, neutrals promptly sent warships to the scene to protect their nationals. These ships were well equipped, and so great was the traffic that it became necessary to hold a meeting and apportion certain hours of the day to the ships of each nation.

In 1914 the United States engaged in a quasi-war with Mexico, and wireless played a large role in the conflict. Practically all the telegraph lines were down; the ships off the coast of Mexico were out of touch, except for wireless. Commercial communications had come to a standstill within Mexico, and the Navy stepped in. For several years, the Navy had been authorized to set up radio communications, as long as said system did not interfere with any private companies. As a result, practically every Navy land station, and all Navy vessels, acted as commercial radio stations. In Mexico this paid off, as the Navy filled in for the Mexican telegraph service. On the West Coast, a chain of ships was established up the coast to San Diego; in the Gulf, construction was rushed on a station at the mouth of the Rio Grande. However, the fleet on the East Coast was in almost direct contact with Washington, and all commands came from the Navy Department (theoretically).

So radio passed through its growing pains, until it stood ready with the airplane and submarine to change the face of battle.

V

Wireless Weapons

With the radio as a means of communication proved feasible, the thoughts of inventors turned to radio as a means of remote control. Only now, as the century reaches midpoint, and the experience of two world conflicts is behind us, has this use of radio reached maturity. But experiments in radio control commenced soon after Marconi made his first transmissions.

By 1901 Cecil Varicas of England claimed to have a successful radio-controlled torpedo which was only one-third as expensive to manufacture as the standard Whitehead torpedo and almost equally efficient. Experiments continued in other navies, the French generally taking the lead, until in 1914 the American, J. H. Hammond, produced what appeared to be the ultimate.

Hammond’s torpedo was in reality a wireless-controlled boat, which operated at high speed and was controlled from a shore station. In tests Hammond was able to guide his missile by radio impulses as far as the eye could see, in practice to a distance of eight miles. The vessel traveled at a top speed of 33 knots and was extremely responsive to its controlling signals, which were effective to fifty miles. The Coast Artillery Corps of the Army was most intrigued by the weapon, but the Navy also demonstrated interest. There was, however, the possibility of the operations signals being jammed, a stumbling block which plagued all early inventors of radio-controlled devices.

In the field of mines, radio-control was also attempted, and by 1914 the Italians claimed to be able to explode mines from a distance of 2500 feet, though the mines were fifty feet under water and 450 feet from shore. In the same year, another Italian announced that he had perfected a device to explode powder at a distance by means of radio. This caused quite a stir among military circles, but appears to have been untrue.

In the air, as far back as 1897, there was a patent granted for a radio-controlled dirigible, but the field seems to have been abandoned upon the introduction of the airplane. Communications with airplanes were generally unsuccessful before the outbreak of World War I, for the vibration and noise prevented satisfactory reception. However, in 1912, it was made possible for an airplane to send messages to the ground, and use was made of this invention in the World War.

When war broke out in 1914, the navies of the world had taken the fullest possible advantage of the wireless method of communication. The major warships of all nations were furnished with the latest and most efficient equipment available. Figures are difficult to obtain as to the exact number. It is known that at the end of 1913 some 435 ships of the Royal Navy had wireless sets installed, and that 200 ships of the United States were also equipped. As far back as 1907, 140 German warships had the Slaby-Arco system, as did 126 Russian naval craft.

Unfortunately, the desires of the navies did not always coincide with the wishes of the people, as represented in their legislatures. The story has been told of how Germany won the race for world-wide high-power chains; but in addition to the British failure, neither the Russian chain across the Siberian North nor the French chain through Africa was completed, though both were under way, as was the American.

Germany entered the war with the advantage of a long lead in the field of international communications by radio. Not until late in the war was this lead curtailed, as the Allied troops captured the German stations and succeeded in cutting Germany off from the rest of the world. Radio has played a role in world politics and strategy since its invention, but never has it equalled its importance as in the early part of the World War, when it saved Germany her shipping.

By 1914 radio had grown from a mere scientific toy to an article of commercial and military value. It proved during that conflict to be as revolutionary as the new inventions of the airplane, tank, and submarine.

VI

The Rise of Radio in the United States Navy

The United States Navy had, during the early years of the twentieth century, five points of policy which were followed at all times. The policy appears to be still in force today. The five points which have guided the Navy are:

1. To keep the Naval Radio System, especially in the fleet, in a more advanced stage of development and efficiency than that of any other possible potential opposing fleet for service in the event of war.

2. To insure the maximum protection to life and property at sea.

3. To make the United States self-sustaining as a nation in radio with respect to its industrial, technical, and operational features, so that the radio requirements of the Navy, the Army, and our national interests in general could be met by American manufacturers with American labor instead of having to import radio equipment from foreign countries to meet our national needs.

4. To remove the disadvantages of unsatisfactory trans-oceanic cab'e services of non- American ownership and operation by the utilization of transoceanic radio service of American ownership and operation.

5. To make the United States as independent in radio as it is in political matters.

Radio first made an entrance into the United States Navy in 1899, when, at the request of the Navy Department, Marconi installed some of his equipment for tests on three American warships. In this year also, wireless was first mentioned in the annual reports of the Department.

The annual report for 1901 recommended the trial installation of Marconi rigs on several warships and also related that several officers were being given introductory instruction in radio at the torpedo school in Newport.

These sets proved unsatisfactory, and in 1901 the Department sent three men to Europe with instructions to investigate the various sets which were then in use and to bring back the better ones for further tests in the United States. The annual report stated that the Navy was going slowly in the matter of radio, because of the extravagant claims which were being made by the inventors of the several types of equipment then in use.

In 1902 the men returned from Europe, and after three months of experimentation, it was decided that the German Slaby-Arco system was the most satisfactory of the foreign sets. This equipment was installed on several ships, but in the maneuvers of that year, the American De Forest equipment was also found very satisfactory. The Navy became increasingly interested in radio, and the annual report requested that more men be assigned to this field, pointing out that foreign nations were paying much more attention to this new form of communication than was the United States. It was in this year also that the Navy first pleaded for government control of wireless, pointing out the difficulties which would arise from the anarchistic situation then existing.

In 1903 the Navy founded an operator’s school at the New York Navy Yard, and the annual report stated that thirteen men were in training there. In addition seven ships had been equipped, and five shore stations established. This was the year that the Navy informed Marconi of its terms, and all equipment purchased was of the De Forest or Slaby-Arco design.

As radio had grown up in the United States, various government agencies had established their own networks, and interdepartmental strife became quite severe. The Navy, Army, Weather Bureau, Treasury, and Department of Commerce were all fighting for control of the wireless. The Navy’s position was that the Navy should have control of all government stations on the coastline, and should man these stations with their own personnel, so that in wartimes the operators would be familiar with the various procedures, codes, and so forth. The Navy did not care to rely on civilian operators and promised to give the other departments what service they needed. In 1904 President Roosevelt set up an interdepartmental board to iron out the problem. The board eventually came out with the following recommendations concerning the Navy:

1. The Navy should equip and install a coastwise chain of radio stations on all coasts, insular possessions, and in the Canal Zone.

2. Naval Stations equipped with wireless should transmit, free of charge, all weather information.

3. All vessels receiving the above weather information were requested to submit to the Weather Bureau, at no charge, all weather information.

4. Naval radio stations were to give free message service to ships at sea, provided such service did not interfere or compete with commercial companies.

These recommendations were ordered into effect by the President at the end of July, 1904, and had a far-reaching effect. Though not strictly law, they exercised a great influence upon the growth of Navy radio, and the growth of radio in the United States, for they committed the Navy to a giant wireless system of its own, therefore paving the way for government expenditures and a great market for American manufacturers.

By mid-1904 the Navy had 18 shore stations, and 33 ships (including nine in the Asiatic Squadron) equipped with wireless. One year later there were 23 shore stations and 44 ships equipped. In this year (1905) the Navy first commenced the regular transmission of weather information and time signals, and also began the long distance records that have marked the history of Navy radio. Washington was able, during one evening of the year, to converse with the battleship West Virginia, when that ship was in the Gulf, over 1000 miles away.

1906 saw the completion of the West Coast chain of Navy radio stations, tying in the entire coast in a relay system as the East Coast was already tied. In the same year Navy radio proved its usefulness in a national emergency, when it proved the only means of communication from earthquake stricken San Francisco. But the year had its bad points too, for it saw the emergence of the amateur, or “ham,” as a menace to naval communication by radio. The dry-dock, Dewey, in its trip across the Atlantic was in constant communication with the mainland, but several of the messages were well scrambled by some high school boys with the aid of an old Morse key, a broken incandescent lamp, and a few dry batteries.

In 1907 occurred the introduction of radio-telephone into the Navy, as all the ships which went on the Around-the-World cruise were equipped with an apparatus capable of some ten miles. Wireless was also used by the fleet in contacting the various escorting squadrons which met it upon its arrival in foreign waters. By 1907 all the battleships and most cruisers were equipped with radio, with 39 shore stations in support, four of which, Colon, Guantanamo, San Juan, and Key West, were of reasonably high power. The United States led the world in the number of shore installations.

Transpacific communication was established in 1908, and the Connecticut, en route from Hawaii to New Zealand, was able to exchange messages with Point Loma—a distance of 2900 miles. Wireless became truly a means of communication, as over 51,000 messages were received by Navy installations. In the same year the Navy requested Congress to pass legislation regulating radio.

1909 saw the Navy launching out into the higher frequencies, as the Salem and the Birmingham carried on tests with Brant Rock on their cruise across the Atlantic. Efforts were made to enlist interest in radio from the Naval Militia. The New York wireless school expanded to 235 students.

Portable equipment for landing parties was experimented with in 1910, and further experiments were carried on with stability under battle conditions, as it was found that heavy gunfire threw off the wireless sets then in use. The use of radio by naval personnel was the subject of General Order Number 82, which said that only official business was to be carried on with naval equipment; the Navy later regretted that this order was not enforced strictly.

Alaska was the site of expansion of Navy radio in 1911, as a station was built at Kodiak, and three more were started. Emphasis was again placed on portable equipment, and in June the contract was signed for the great installation at Arlington.

1912 was a big year for Navy radio, as the Office of the Superintendent of the Radio Service was established, and by the Radio Act of 1912 the Navy became a commercial system, in competition with Marconi and the other foreign systems. Arlington was completed, and the rest of America’s high-power chain contracted for. Twenty-seven stations were in construction in the Philippines, most of which were to be under Navy control. Radiotelephone proved successful in some degree, as a Navy transport succeeded in contacting a shore station in California 1300 miles away. Most of the ships were equipped with radio, and 45 shore stations were in operation. Wireless transmission was successful from an airplane at Mare Island. Harvard set up a radio school to which the Navy sent students.

In addition to making Navy radio commercial, the Act of 1912 removed the thorny “ham” from the Navy’s side. In the hearings, the Navy testified as to the interference caused by the amateur, citing the example of the destroyer Terry, which sent distress signals from off Bermuda. Though the operators at the Brooklyn yard were able to pick up the SOS, “ham” interference was so great they were unable to hear the ship’s position. The amateurs, in their turn, replied

... by reading transcripts of conversation which they had picked out of the air, between naval officers, or sometimes between officers and women—cheap gossip, intrigue, assignations, amatory trivia, stuff which caused more red faces in the Navy than it had known in many a day. . . .

However, the Act was passed which limited the activities of the amateurs, and since then the Navy and the “hams” have been on friendly terms.

In 1913 the cruiser Salem made a trip across the Atlantic, carrying on continuous contact with the United States. This was the first thorough test of the state of radio communications in the Navy. Distance records before were but flukes, as was the communication between Key West and Cairo, 7000 miles, which occurred in the same year. Also in 1913 the Navy established the Naval Radio Laboratory in the Bureau of Standards, whence later came many improvements.

1914 saw radio of great use in the Mexican troubles, and the installation of equipment capable of transmission half-way round the world at San Diego and on the Flagships. Some 200 ships of the Navy had equipment, and shore stations were in operation in the following places all over the world: Portland, Maine; Portsmouth; Boston, Cape Cod, Nantucket Light Ship; Newport; Fire Island, New York City; Philadelphia; Annapolis; Washington; Arlington; Norfolk, Diamond Shoals Light; Beaufort, Frying Pan Shoals Light; Charlestown; St. Augustine, Jupiter, Key West, Pensacola; New Orleans; Bremerton, Tatoosh, North Head; Cape Blanc; Mare Island, Eureka, Farralons, Port Arguello, San Diego; San Juan; Guantanamo; Colon, Porto Bello, Balboa; Honolulu; Guam; Cavite, Olongapo; Peking; St. George and St. Paul in the Pribilofs, Unalga, Dutch Harbor, Kodiak, Cordova, and Sitka.

By the outbreak of the World War the United States was among the first rank powers in the radio world.

*During the war, until captured, this station continually sent instructions to German agents in South America.