Introduction

The writer has been hoping for a long time that some of the many really expert destroyer commanders would write about some of the results of their experiences and observations of handling destroyers.

Finally in sheer desperation, perhaps with the idea of "starting something," some observations of three rather busy years handling and watching others handle them under many and varied conditions have been jotted down. These notes are not intended as a treatise on "How to Handle Destroyers"; they are simply a few observations concerning some of the mistakes often made.

It must be remembered that no two vessels handle alike; also, that no two men will handle their ships exactly the same. No fixed rules can be laid down, and it is not the writer's desire to have these remarks considered as such. After all, experience is the best teacher, but it is hoped that these notes may be of value to the new men coming to command destroyers.

The handling of a destroyer alongside a dock or alongside other vessels is to most destroyer men a never-failing source of fascination. A destroyer is a light vessel, very much affected by the wind, which has an effect on the high bow like that on the jib of a sailing vessel; a vessel of high power; swift; quick to answer the rudder; with fairly small turning circle; and withal so delicate that a little misjudgment may quite easily result in torn plates, a mowing down of your own or another's stanchions, bent gun training gears, damaged torpedo-tubes, damaged propeller guard, or propeller.

And never are the conditions exactly the same! How many times the young skipper, exasperated by what he thinks is a landing not 100 per cent seamanlike, exclaims, "Now why in the name of all that's holy didn't the darned stern swing in as it usually does!" It is so easy to overlook one of the many little points, as wind, eddy currents, etc., a forgetfulness that may mean overtime work for the repair gang.

When many destroyers are based on a port, it becomes necessary for a great deal of this kind of ship handling, and experience has shown that under such conditions there will be a good many cases of minor damage. Our destroyer repair ships overseas will testify that the hull and upper deck fittings are frail structures, judging from the way they had to work to keep the destroyer on the job.

Different Destroyer Types

Before proceeding with an account of the mistakes commonly made, it would be well to examine some of the points wherein the several types of destroyers differ, in regard to maneuvering qualities.

The vessels before the 700-ton class are not considered in this article.

1. Triple Screw 700- and 750-Ton.—These have small fast moving screws, small turning leverage and small backing power.

In order to turn in a short space it is best to use the rudder and get way on, shifting rudder when dead in the water. The kick of the "inboard screw" backing as it churns when started is of great assistance.

The wind effect on the high bow of these destroyers is most marked, especially when backing.

The twin-screw boats have better turning leverage, but have the disadvantage of less backing power than later boats.

2. Thousand-Ton Destroyers with larger and slow moving screw, greater turning leverage and greater backing power, can ordinarily be turned in a very small circle, using one screw ahead and the other backing. They turn best with a little ahead motion of the ship. The wind has less "jib effect" on these on account of the high boat skids aft.

3. Twelve-Hundred-Ton Destroyers having more power are still easier to handle, but care must be taken to use this power judiciously, in order not to start ahead or astern with a rush. It has also been noted that one must anticipate a little, for a signal from the bridge does not result in a reversal or starting of the engine as quickly as in the smaller ones, and when they do start, as one captain said, "You know it." This slowness of starting may apply to only a few of the boats, for another captain says that you get the effect of a reversal or change of engines very quickly.

The destroyers of the latest design should be particularly easy to handle, on account of their cut-away stern. This makes them very sensitive to rudder changes. Their deeper draft when loaded will make them less susceptible to the wind, which is a bugbear to most destroyer men, when it cannot be used to help. It may be remarked that the officer of the deck and steersman will have to be very much on the job when running before a quartering sea, due to excessive yawing, especially in shallow water.

Reasons for Mistakes

- Insufficient knowledge of the maneuvering qualities of the ship; how wind and tide effect its handling, and how to make allowances therefore.

- Use of excessive speed.

- Use of too little power.

- Lack of confidence; indecision.

- Insufficient or improper use of lines.

The remarks in this article are chiefly applicable to vessels of the "1000-ton" type, except where a certain type is specifically mentioned.

Insufficient Knowledge

The knowledge of how ships will act under varying conditions is one which cannot altogether be learned from books, tactical data, or the thorough analysis of the effect of the rudder and screw in Knight; these should all be studied, but before one can become an expert at handling his ship a certain amount of experience must be had to round out his knowledge.

The quickest way to turn, in point of time, is at a fair speed, both engines ahead, and with full rudder. The slowest is with practically no way at all, one engine ahead, the other astern.

Therefore, desiring to get around in the shortest time, you should turn with as much headway as possible, consistent with safety. Ordinarily, to turn in a limited space with boats of the 1000-ton class, it will be found best to so regulate the speed that the effect of the engine going ahead is a little greater than that of the engine going astern. And, moreover, the more power (not speed) the quicker the turn.

But with the lighter 700- and 750-ton boats, especially those with the Parsons' installation, it will be found that it is almost impossible to turn in a limited space without surging back and forth, and the continuous backing of one screw while the other is going ahead is hardly worth while, unless wind conditions are such as to help push the bow around. With these boats, the effect of the rudder is greater than screw current or sidewise pressure of the screw, as long as the ship has way; so that it is best not to shift the rudder, when the inboard screw is reversed, until the ship has lost all headway. An exception may be noted here that when the inboard screw first goes astern, an appreciable kick of the stern is felt which decreases as the headway is diminished. So it often may be found convenient to keep one engine going ahead, and to start and to stop the inboard engine (going astern) from time to time. When the outboard engine starts ahead, the screw current acting on the rudder tends to diminish the turning effect of the rudder, due to ship moving ahead, and you must be prompt to shift the rudder.

A big factor with these boats is the lack of power. If you have only two boilers lighted, especially when you are just getting under way, any continued work with one engine backing and the other going ahead will soon kill your pressure, and you may find yourself adrift, not under control.

If it is necessary, due to vessels, buoys, etc., to gain distance astern while turning in a limited space (handling a "1000-tonner" or greater) the following point must be remembered: The rudder should be shifted when headway is lost; but, when going ahead after backing, the rudder should be shifted (or better yet brought amidships) when the "outboard screw" is started ahead.

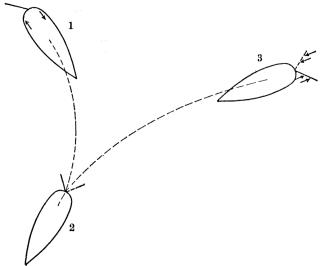

In Diagram "A" a destroyer at (1) , with right rudder, port screw ahead, starboard backing, turns quite well. Then port engine is stopped, speed of starboard engine (backing) is increased. When dead in the water, rudder is shifted. Ship will turn, but not as much as when going ahead, because the effect of screw current is not so great. Now in position (3), if port engine is started ahead, it will be found that the screw current acting against the left rudder will tend to throw the stern to starboard, nullifying what you want to do. On the other hand, if the rudder is immediately shifted, the pressure of the water due to the ship's sternboard will also tend to throw the stern to starboard.

Therefore, in this case, it will probably be found best to put the rudder amidships until sternboard is checked, then give right rudder. Or, put rudder amidships, go ahead standard or full both, give right rudder immediately, and as soon as sternboard is checked, slow down to safe working conditions. This is a good example of the use of power, as differentiated from speed, a subject that will be touched later.

Be sure and know the right time to back in making a landing. A landing made when headway is checked too soon, or too late, is not a pretty landing, but it is better to check it too soon, rather than overrun. A little experience will show when to slow, in making the approach, when to stop, and when to reverse. For example, a certain type of boat, making a straight or parallel landing, may have the engines slowed to one-third four lengths away, stopped when stem is one-half length from where stern is to be, backed two-thirds when stern is half a length from its proper position, and engines stopped when headway is nearly checked.

The effect of the wind should be carefully studied. If wind is quite fresh and parallel to the dock or ship you are going alongside of, be sure you do not get your bow canted either way. If bow is canted outward, it will be nearly impossible to make a good landing. If is canted towards the dock or ship you run serious risk of doing damage. This is the most frequent cause of damage to other destroyers and your own. For the wind blows the bow in more and more, and if headway is still carried, the anchor or bill board will make a clean sweep of your neighbor's stanchions. In some cases, if you back hard enough, the stern may go in and the bow out, due to pivoting, but more likely the bow will . come in, you will gather sternboard, and your neighbor will be raked worse than ever. And you may leave your anchor on her whaleboat davits. Best thing to do is not to attempt to get out clear. Use the engines to stop headway, get out some lines quickly; hold her there and let her swing parallel. This will localize the damage, at any rate. Then you can tell your brother captain you will send your blacksmith and carpenter over to repair the damage. This last is an important bit of etiquette that should not be forgotten by young destroyer skippers!

The effect of the wind is strongest when the ship is backed, and is most marked in the 700- and 750-ton classes. They will back dead into the wind. The bigger boats tend to seek a heading with wind on the quarter. This is due to the high forecastle of the former; while the latter have boat skids or other top hamper more nearly amidships. In narrow quarters it is very dangerous to lie dead in the water with wind abeam. You should have room ahead, for if you try to twist her without getting way on, you will be confronted with a wearisome and often impossible task.

If the wind is onshore, be sure and keep well off, and keep the bow a bit further off than the stern, as the bow will come in much quicker.

If the wind is offshore, a certain amount of speed is necessary in order to make a good landing, and springs must be used. A method of coming alongside under such conditions when a parallel approach is impossible will be treated later.

The current will not have the effect of the wind in blowing off the bow, but it plays an important part, and often is not setting the way you think it is. It is especially difficult to judge when making a slip, for the chances are the current is nil inside the slip, or there even might be an eddy current inshore, opposite to the direction of the current offshore. The coal slips at the navy yard. New York, the slips at the torpedo station at Newport, and the old dock at Pensacola, are examples of where eddy currents may be encountered. Careful judgment and experience are necessary.

The question of what the ship will do with one or both screws astern is not well understood by many captains, and a better knowledge will not only avoid damage by knowing when not to back, but also knowing how to back may give one the opportunity to make some very pretty landings.

Always leave the dock or ship by going ahead if possible. The ship is under much better control when going ahead, and the engines are better able to give you what you want. If you back away, the bow may pay off toward the dock or the vessel alongside, for, as has been remarked, the ship is more at the mercy of the wind, etc., when backing than when going ahead. Furthermore, the initial "kick" of the engines going astern may not be equal, causing the ship to cant one way or the other.

The "kick" comprises two elements: (1) The sidewise pressure of the blades deepest immersed (very noticeable when the screw churns on first starting); and (2) the pressure of the screw current on the hull. The first has the strongest effect and it diminishes when the ship gathers sternboard.

In going ahead you should not give much rudder to swing the bow out, for the stern will come in fast, and your propeller guard may leave a long mark on your neighbor. In some cases it will even be necessary to shift the rudder, to swing the stern out, in order to avoid fouling the anchor chain or buoy of your neighbor. If there is a slight tendency of wind or current setting you down on your neighbor, often a good bit of speed is necessary.

If conditions are better for backing, it is best to get away quickly in most cases, in order to obtain some steering effect of the rudder and to minimize the effect of the wind. If you are between two other boats, back both engines at a good rate, say two-thirds, or even full speed, to get the ship started. The wash of the screws will carry the sterns of both neighbors away and you will come away clean. Needless to say, slow down to a safe speed as soon as you are clear.

If the harbor is rather crowded, having backed away, but clear astern, it might be well to continue backing until you have plenty of room to turn. Only, be careful about crossing the bows of vessels at anchor. When going astern be careful how you use your rudder. A quick shifting of the rudder while you have sternboard may result in the rudder taking charge, on account of the pressure of the water on it, with a probability of a jammed steering gear, and perhaps a damaged steering engine.

Do not forget that when going ahead with full rudder you do not make ground to the side immediately. The ship, though turning, will range along its original direction of motion, and may even be set initially to the other side, due to the kick off of the stern, for the stern starts first, not the bow. We all know this truth, but occasionally forget it in the business of maneuvering.

In any maneuver try always to have an alternative in case your planned maneuver goes awry. A good habit of mind is to keep thinking, "Now if such and such a thing happens, what should I do?"

Under certain conditions do not hesitate to use an anchor to assist your landing. In a crowded harbor with a strong breeze or gale blowing, when you cannot get pointed into the wind to make a parallel landing alongside another boat, it is by far the best scheme to assist your turn by means of an anchor. Drop it so that you use as little scope as possible without dragging, and at such an angle as to be able to use it to keep the bow from crashing into your neighbor. Do not think it "bad seamanship" to use an anchor when it will prevent damage.

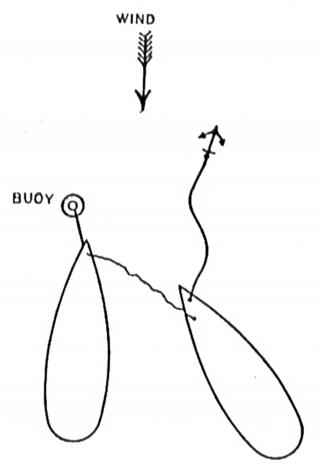

Diagram "B" shows that it is possible to use anchor and bow line to assist in turning by heaving in or checking both judiciously, at the same time using the engines to assist in turning. Be careful not to drag the anchor. This is most likely to occur when the ship is broadside to the wind. It is better to veer somewhat at that time and heave in when the heading is about as shown in sketch. When the stern is in far enough, and your lines are out, the ship may be heaved ahead to break out the anchor.

One captain turned his ship by getting out a bow line to the stern of another boat, let the ship swing to the wind and current, cast off and came alongside very nicely.

Do not forget, too, that your ship does not handle the same in light conditions as she does deeply loaded. This will be particularly noticed if there is any wind; your leeway will be greater in light condition.

Speed

By speed is meant actual way through the water. You may often signal full speed on your engine-room telegraphs, if it seems best, but do not continue it long enough to get up much speed.

Speed is a good thing to use, only, (1) when you have to, and (2) when you have lots of room. Even in these cases do not use more than necessary.

If something goes wrong in a crowded harbor, such as jammed rudder or engine disabled, you will be harder pressed to win through without damage, if you habitually use high speed.

The same reasoning applies, with more emphasis, in making a landing, especially alongside another boat, or when there is something ahead, as in making a slip.

The ideal way to make a landing is to use only enough speed to be sure your ship is under control. This speed will depend on circumstances, as some of the examples already given serve to show.

I have observed that the longer an officer commands a destroyer, the more he reduces the speed of his approach. Nearly every destroyer captain will remember a period in his career when he loved to make spectacular flying landings. Very likely he "got away with it," but with longer experience he grew wiser, and was content to play safe.

And in this connection, if you misjudge your landing and see that you cannot avoid hitting, be sure to get the way entirely off the ship if possible; get out a line and hang on until you have swung. If one destroyer noses into another in coming alongside, an attempt to twist her around will almost invariably result in scraping along leaving a long trail of devastation behind. If you see you are going to be set against the corner of a dock, take your damage in one place, rather than to extend it for 15 or 20 feet or more along the side.

Power

Often in an emergency a captain may take half-hearted measures to avoid collision or damage. Or, in turning, he unnecessarily delays by use of too little power. If he were the only one entering harbor it would not matter much, but usually boats will be entering harbor in divisions or flotillas, and others will be delayed. Most of us know how exasperating it is to lie to at the harbor entrance, waiting for the chap ahead to get straightened out and in his berth.

Inasmuch as most destroyers have plenty of power, it may as well be used, only be sure not to get too much way on the ship.

Thus in turning in a limited space, it is foolish to ring up one engine one-third ahead and the other one-third astern, when you have enough power to ring standard ahead and two-thirds astern, changing either engine if too much headway is obtained. Then you will get around quicker and the speed through the water will be no greater.

Here are two ways of handling the engines of a ship turning in a limited space, the methods of two different officers—and there are nearly as many methods as there are destroyer captains. It will be assumed that the ship is turning to starboard:

First Method.—Start with port engine two-thirds ahead, starboard backing two-thirds. Then do not touch starboard telegraph at all; vary port engine only, shifting it to one-third ahead or standard ahead as much as is necessary to keep from forging ahead or astern too much.

Second Method.—Starboard engine back one-third; port engine ahead two-thirds. When ship gains too much headway, shift to two-thirds back on starboard engine; one-third ahead on port engine. Shift to the original setting when you gather too much sternboard. Continue like this, making no other changes except necessary rudder changes. In this case the command may be simply "reverse." There is little possibility of giving the engine-room the wrong signals.

Take your pick, or choose your own method

It must be clearly understood by the throttle men just what the captain wants when he rings the engine-room telegraphs. A certain go ahead speed should be established as a maneuvering "standard speed," say 18 knots (15 knots will probably be better for 750-ton destroyers). Then you have one-third speed, six knots; two-thirds speed, 12 knots; full speed, 23 knots (five knots greater than standard, which is often designated for full speed in destroyers).

It is more difficult to base backing speeds on revolutions, and most destroyers have designated pressures for one-third, two-thirds, and full speed astern. No arbitrary pressures can be given, but the backing pressures of the ship should be so arranged that with one engine backing one-third and the other ahead one-third, the ship will move very slowly ahead.

A very important point arises in this connection. The throttle men may do one of two things when a backing signal is received: (1) Open throttle wide so that gage registers the designated pressure immediately, then throttling to keep the pressure there; or (2) he may open it gradually until the gage registers the desired pressure.

Of these, to ray mind, the first is preferable in maneuvering, though perhaps the second is better from an engineering point of view.

However, in maneuvering, the kick given by the engine churning when first started back is often of exceedingly great help to the ship handler, and that effect is greatest if the throttle is opened wide at once. Furthermore, the result of a given signal is more apt to be the same to-day and to-morrow, a most desirable thing. For if the engines perform differently at different times, when the same signal is rung, the captain will truly have a terrible task to "learn by experience."

Lack of Confidence

This hardly needs discussion, it is so evident, as in everything we undertake, that confidence is half the battle.

In passing, it may be remarked that of two officers of equal ability starting out with their first commands, if one has the luck to make a perfect landing under difficult conditions, on his first attempt, he will usually continue to make good landings; whereas the other may slip up, knock down a few stanchions, dent in his bow, or knock a hole in the dock, and it will take a long time for him to get to normal.

Use of Lines

It is not within the scope of this article to go into details of how to handle the lines under all circumstances. But the proper handling of lines in connection with the proper handling of engines and rudder is the truest test of a seaman.

The most useful lines are the forecastle spring and the after spring. Next to this a breast to the capstan, and a breast aft, the latter to be made fast only when the ship is sprung in, or worked in by the engines, to the proper position.

The main thing is to obtain intelligent cooperation between the captain and the officers or men in charge of lines. To this end the latter should be indoctrinated so that they will know what to do without the necessity of signals or of bawled out orders.

When a "parallel" landing is to be made, under good conditions, the smartest method is for the captain to hold all lines on board until the ship is nearly abreast her proper position (and nearly dead in the water), toot a whistle, throw out all lines simultaneously on this signal, order engines secured, turn over the securing of the ship to the executive officer—and go below.

But when conditions are such that a certain amount of work must be done to get the ship alongside, the people handling the lines must know what the captain wants. An improper use of lines often will get things badly mixed up.

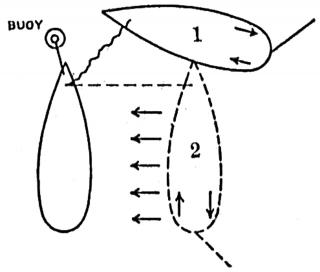

The following method of getting alongside a dock or vessel, when it is impossible or inconvenient to make a "parallel" landing, is especially good in landing when an offshore breeze is encountered. Having once tried this method the writer has used it continuously, and considers it a very pretty way of making a landing:

Proceed fairly directly to your assigned berth, and get your bow close enough to get out a line as in Diagram C, position (1). Keep this line entirely slack and twist the ship around to a heading parallel with the dock or ship with the engines, starboard engine backing say two-thirds, port ahead two-thirds, and rudder full right. Change one of these engines in order to prevent going ahead or astern. It's easier to remember what you are doing if you only use one. When you are about parallel, (your bow will have paid off by this time) take line to the capstan and heave round. Then by proper manipulation of the engines (starboard backing, port ahead) and the line, the ship will breast bodily in crab fashion, and all that will be necessary at the last will be to get out more lines and secure. When you are parallel, the power of the engines must be reduced, as they kick the stern in faster than the capstan can pull the bow in. When about lo feet away, stop everything, otherwise you will come in with a decided bump.

This same method may be used in getting away from a dock against an onshore breeze if there is a buoy or something to run a line to.

Handling at Sea

This does not properly come within the scope of this article, and so will not be discussed at length. However, emphasis should be placed upon the tremendous amount of leeway a destroyer will make when there is a strong wind. If the wind is ahead your speed will be cut down a little, perhaps as much as lo per cent in a strong breeze, and a great deal more in a gale. Most of this is probably due to the sea, however. With the wind about abeam or a little forward of the beam, you may find yourself 40 or 50 miles to leeward of your dead reckoning course in 24 hours. With the sea on the quarter, however, the ship will yaw so much, the stern being pushed to leeward, that the leeway may be counterbalanced, and you may even find that you have crept slightly to windward. No rules can be laid down concerning this, for it depends on the character and period of the sea, in addition to the strength of the wind.

With a rather heavy sea dead astern one would think the ship would be driven farther than the dead reckoning would give. This may often be the case, but to a much less extent than we would suppose. This may be due to the climbing up hill and down hill a destroyer would do under these conditions.

In Heavy Weather

Here are the different courses of action open to a destroyer forced to heave to in a heavy gale:

- Head into sea, or with sea two points on the bow, at the lowest possible speed, lee screw making more turns than the weather screw, to keep the ship from falling off.

- Take the position the ship would naturally take, engines stopped or moving slowly ahead.

- Sea astern or slightly on quarter, "running before it" at fair rate of speed.

- Sea astern or slightly on quarter, engines turning just enough to keep steerageway.

Every time two or three destroyer captains begin to discuss bad weather and how the ship should be handled in a hurricane, you will hear two or three different expressions of opinion, based on actual experience.

So my opinion based on experience in two well-known howlers, one January, 1912, 500 miles off the Atlantic Coast, the other in December, 1917, several hundred miles northwest of Cape Finistere, is only my opinion, and is in no way authoritative. And both times the boat was of the "flivver" type, i.e., 700- or 750-ton boats. But it is believed that the same remarks will apply to the larger boats.

Now as to the first course of action (lying to, heading into the sea): With speed sufficiently reduced the ship will ride quite well, though pitching violently and occasionally taking a sea. If you head dead into it you are likely to duck under an exceptionally steep wave and ship a huge sea. It is better to keep about two points off. But it is necessary to maintain a certain amount of speed to steer, and the greater the force of the wind the greater the speed necessary. And the greater the speed, the more seas will be shipped, and the more the ship will pound. In my one experience of trying this method the ship was pretty badly damaged.

Nearly all the destroyers doing convoy work had broken frames forward, the result of pushing the ship against heavy seas. This is a different condition from that under discussion the necessity of staying with the convoy in the war zone making it necessary frequently to steam into a sea at too great a speed in ordinary rough weather. But the same liability to damage exists in heavier seas and with more moderate speeds.

The second course (lying to in a natural position), while safe enough, as far as danger of swamping is concerned, is so utterly uncomfortable and hard on the personnel, due to violent rolling, as to preclude it from consideration, even if there did not exist the danger of rolling out the masts, smoke-pipes, and perhaps even rolling the boilers out of their saddles. As a matter of fact, destroyers have shipped heavy seas in this position. A sea sweeping across the deck of a destroyer is not a pleasant thing.

There remains, then, "running before it," and "lying to" with bare steerageway, sea astern or on the quarter.

Perhaps I have never given the former (running before the sea) a good trial. In the storm of December 17, 1917, on the Reid, lying to with sea astern, an increase of speed caused greater yawing, with threatened pooping, and we slowed down very soon.

We found it best to keep the sea a trifle on the quarter, in which position, with the use of oil, we rode beautifully. The ship yawed a bit, and the fantail was splashed with spray, but no dangerous seas broke on board. In some kinds of heavy seas, a destroyer can doubtless run at good speed, but I believe that, all things considered, it is safer when riding out a "storm sea" to steam as slowly as possible.

We tried heading into the sea, and did not fare very badly, but after shipping one or two seas it was decided to turn again, and keep the sea on the quarter.

With a destroyer there is no sense in waiting for a propitious time to turn, for a turn of 180 degrees in a heavy sea is a long operation. If done at slow speed, however, she will probably bob up over the sea like a cork, but she will be well shaken up, during the operation, and there is always the danger of being swept by a sea.

The Reid sustained her greatest damage when speed was increased in order to turn and avoid a ship suddenly sighted a short distance ahead. This increase was from about six knots to about 12 knots. When the sea was nearly abeam, one wave swept over the deck, taking with it various items, such as boats, chests, potato lockers, etc., also, worst of all, our engine-room ventilators. A second sea coming over went down these openings, resulting in an engine-room half filled up, water entering lubricating oil tank (having broken the gage glass) and directly afterwards hot bearings.

After this we had to keep the ship dry, and it was necessity that forced us to continue with the sea astern and continue using oil, which was of great value in preventing breaking seas.

Every destroyer captain should be very familiar with the "Laws of Storms," and should practice forecasting the weather. With Knight and the "Sailing Directions" for the particular locality at hand, one can develop into a first-class weather prophet, depending of course on your station, for the weather in some parts of the world is more difficult to understand than in others.

I have been told that a number of years ago two British destroyers went through a harrowing experience in weathering a typhoon in the China Sea. Their experience and lessons drawn therefrom were written for an English publication as being of great interest to the public, and especially to seamen.

But a careful reading of the article showed that these boats had entered the edge of the typhoon, had run out, and then were caught again when it recurved, this time passing through the center of the typhoon, encountering terrific winds and seas. The point of this is, that if they had been more familiar with the characteristics of cyclonic storms, they would have avoided the worst part of their experience.

An Example of Different Ways of Handling a Destroyer

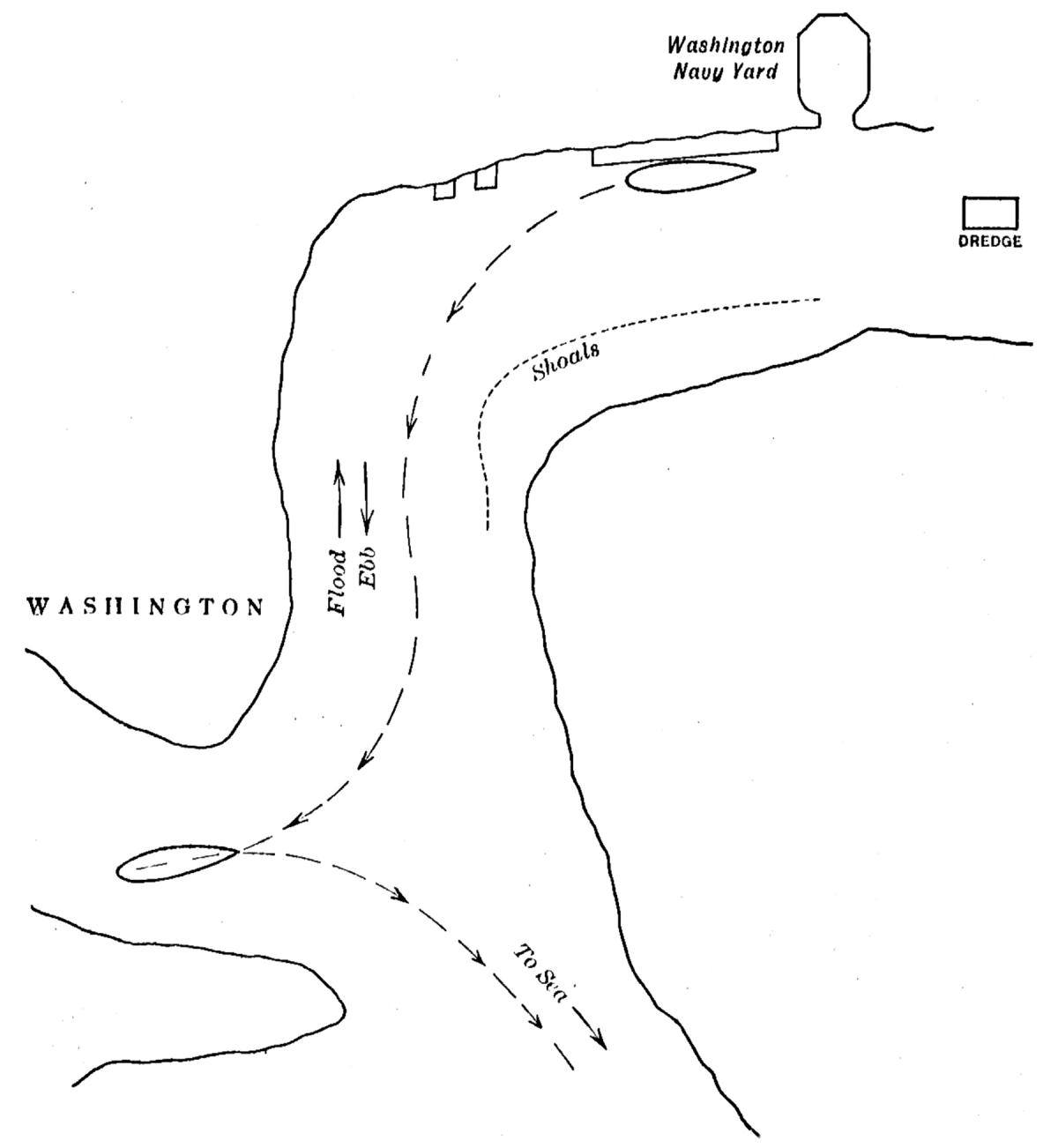

Diagram "D" shows roughly the Anacostia and Potomac rivers, and the Washington Navy Yard. It was quite easy here to make a landing, but somewhat difficult to get away. Type of destroyer: Coal-burning, 700-ton type. The nature of her duty was such as to make it necessary to reduce the time wasted in mooring and unmooring to a minimum.

The ordinary method of "shoving off" depended on the tide. If it was ebbing, the bow was allowed to go out a little, engines started ahead, and when clear the ship was twisted around, ready to proceed down the channel. If on a flood tide, the stern was allowed to go out a bit, the ship backed clear and then turned. This was more difficult, and it was usually necessary to make a complete 180-degree turn, on account of the flood tide carrying the ship upstream. It must be remembered that this was a "700-tonner" and required surging back and forth, shifting the rudder, and working pretty hard to get around. A "1000-tonner" would have had less difficulty in turning.

A better scheme was to wind the ship at the dock. This was not difficult, especially with a flood tide, for then the stem could be held fast against the dock, until nearly around, then the ship backed enough to clear before going ahead.

With ebb tide it was not difficult, except that more care had to be taken to keep the propellers and rudder from touching the dock. In general, the current did practically all the work in this case, the engines only being used to keep the stern clear of the dock.

The next method tried was to wind the ship upon arrival. Coming in on a flood tide, the stem was placed against the dock and held fast, the tide, assisted by "twisting" with the engines, turning the ship end for end. This permitted a "clean get away," when it was time to go.

The last method was to back away from the dock, and, steering by engines and rudder, backing into the Potomac River, where it was only necessary to go ahead and down the river. This is shown by dotted lines.

These various operations were timed, and it was found that the last method saved several minutes.

Conclusion

Most of the foregoing remarks on the handling of destroyers are concerning "the little things that everybody knows," but in nine out of ten cases of damage or poor ship handling these little things are responsible. This article is not based on theoretical considerations, but on actual happenings.

It need not be assumed that a destroyer captain must analyze the forces at work while he is maneuvering his ship, or to have any "rule-of-thumb" methods. More likely, if he has gained some degree of expertness by practice, he will develop a sixth sense; he will handle the ship by the "feel" of it, as it were.

It may be remarked that in handling a destroyer it is best to take station where you can see the water close to the side. In this way you can judge your speed much better than by watching the beach or another ship.

Finally, be sure to give your junior officers, especially the executive officer, a chance actually to handle the ship under good conditions. In this way they, too, will get the "feel of the ship," and when the necessity comes for them to handle the ship in your absence they will have some degree of confidence to help them.

Remembering that there are many different ways of doing it, do not insist on their doing it exactly your way, and do not "butt in" except to avoid disaster. It is much better to talk over the whys and wherefores afterwards. I doubt if even the most phlegmatic "mate" could do well under the fire of his captain's criticisms.