On 15 February 1944, an armada of U.S. Navy ships arrived at the Japanese-held Green Islands. High-speed transports (APDs) lowered landing craft filled with soldiers, and the boats then surged toward their designated beaches. The vessels were American, but the assaulting troops were New Zealanders. Operation Squarepeg—the largest amphibious operation undertaken by the New Zealand Army in World War II—had begun.

The Green Islands, also referred to as the Nissan Islands, lie just south of the equator and 80 miles northwest of Bougainville. The group’s largest feature is Nissan, or Green, Island, which is really an oval atoll (this is likely the origin of the operation’s codename—“a square peg in a round hole”). The thickly jungled islands were home to about 1,150 Melanesians, most of whom lived on Nissan.

In January 1942, the Japanese seized the Green Islands for use as part of a network of barging stations linking their major South Pacific bastion of Rabaul, New Britain, with their troops on Buka and Bougainville. However, apart from breaking this supply chain, there were other reasons the islands attracted Allied attention.

Recapture of the islands would complete the encirclement of Rabaul. Taking off from the Green Islands, flight time for aircraft attacking Rabaul would be roughly halved. Moreover, the creation of a PT-boat base would facilitate the interdiction of Japanese supply barges. Admiral William F. Halsey Jr., Commander, South Pacific, was keen to maintain the momentum of Allied forces’ northward advance, and his superiors, Admirals Ernest King and Chester Nimitz, approved a plan in January 1944 for the invasion of the Green Islands.

Concerns, Force, and Convoy

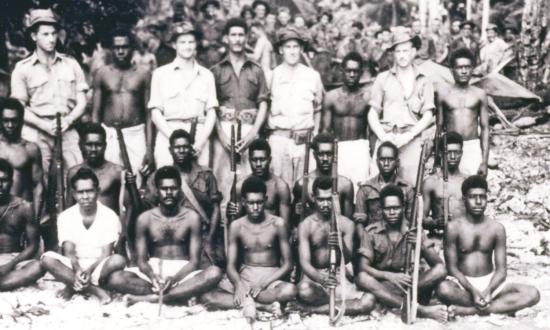

The plan had numerous drawbacks: With Rabaul only 117 miles away, the invasion was a high-risk venture, and a vigorous Japanese reaction was expected. A second factor was the Allies’ lack of information about the islands. This latter concern was dealt with by launching a 31 January commando raid on Nissan Island that involved New Zealand soldiers escorting specialists who examined the hydrography, beaches, and terrain and concluded that the operation was feasible (see “Raiders of the Green Islands,” June 2020, pp. 34–40).

Third Amphibious Force commander U.S. Rear Admiral Theodore S. Wilkinson would command Squarepeg’s amphibious operation. Allied leaders assigned units of Major General Harold Barrowclough’s 3 New Zealand Division—14 Brigade, 3 NZ Divisional Headquarters, and supporting elements—to be the attacking force. By this stage of the war, the Kiwis were combat experienced, proficient in landing operations, and accustomed to working with the U.S. Navy.

The Americans contributed a miscellany of ground support units, including three Naval Construction Battalions (Seabees), one Argus unit to establish and man radar and communication stations, and two Acorn units to operate and maintain an airfield and seaplane base. But the most significant U.S. contributions were warships and transports.

The various units taking part in the invasion, as well as their equipment, heavy weapons, and food supplies, had to be embarked from their locations mainly on Vella Lavella, 250 miles southeast of Nissan, and Guadalcanal. Above all, water supplies had to be transported because of the islands’ lack of potable water. D-Day was set for 15 February, with H-Hour at 0630.

Most of the slower vessels of the invasion’s initial echelon–5 landing ships tank (LSTs) and 12 landing craft infantry (LCIs)—set out from Vella Lavella on D-2 Day, 13 February, while the operation’s 8 APDs (converted flush-deck destroyers) departed Vella on D-1 Day. A further two LSTs, six landing craft tank (LCTs), two small coastal transports (APCs), three minesweepers, two LCI gunboats, and numerous small craft joined the convoy. While each transport unit was escorted by destroyers, Task Force 38—the light cruisers USS Honolulu (CL-48) and St. Louis (CL-49) and five destroyers—covered the convoy’s advance.

One of the oddities of the convoy was the deployment of barrage balloons tethered by steel cables to the giant LSTs. These were designed to snag low-flying Japanese aircraft, or at least make it difficult for them to attack the ships. Unlike their land-based counterparts, the balloons had special fins enabling them to move smoothly with the vessels.

A Bloody Valentine’s Day

At 1916, sundown, on 14 February, six Aichi D3A “Val” dive bombers attacked Task Force 38. The St. Louis, targeted by two of the planes, was desperately zigzagging at 27 knots when they released their bombs. One plane’s three bombs were near misses on the ship’s starboard bow. Two of the second Val’s bombs were near misses off the port quarter, but its third one hit near the cruiser’s no. 6 40-mm gun mount, penetrated the deck, and exploded in living quarters, killing 23 sailors and wounding 20, many seriously.

A resulting fire in the 40-mm shell clipping room was quickly extinguished, as were electrical fires. But damage to the ventilation system resulted in the aft engine room being evacuated due to extreme heat and smoke. Later, smokescreens were laid around the wounded ship, which made evasive maneuvers in anticipation of further attacks. Fortunately, these did not eventuate. It is a testament to the skill of her damage control teams and crew that the St. Louis was able to control the fires and continue functioning. None of the task force’s other ships were damaged in the attack, and after completing her escort mission, the St. Louis would retire to Florida Island’s Purvis Bay for repairs.

At first light, 0645 hours, on 15 February, as the first wave of assault landing craft from the APDs was heading toward its beach, more Val dive bombers appeared and attacked the convoy near the entrances to Nissan Island’s lagoon. Of the 15 aircraft, only six were seen to drop bombs, and these caused only minor damage. Kiwi soldiers on board ships cheered as antiaircraft fire and Allied fighters drove off the dive bombers. Some six Vals were believed shot down.

Orchestrated Landings

Planners had intended for the minesweepers to precede the landing craft, clearing any mines around the lagoon entrances. However, the minesweepers experienced mechanical problems, which delayed them by 40 minutes. To avoid a snarl up, it was decided that the landing craft would simply take the risk and proceed into the lagoon. Fortunately, there were no mines, and the Japanese had not targeted the entrances with artillery.

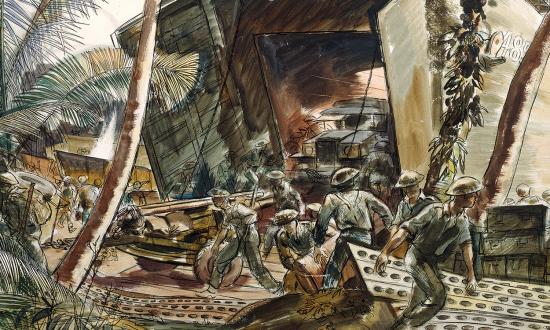

A series of carefully choreographed landings then took place. The first wave of landing craft made its way to Blue Beach on the lagoon side of Pokonian Plantation. The craft landed their troops and were off the beach by 0655. At 0740, these same boats landed a second wave of troops across the lagoon at Red and Green Beaches, Tangalan Plantation. Next, the LCIs entered the lagoon at 0755, and after they beached on Blue, Red, and Green Beaches, troops disembarked down ramps on either sides of the craft. Soon after the LCIs were off the beaches, the LSTs beached on Blue, Red, and Green. Finally, LCTs arrived and offloaded tanks and artillery.

The New Zealanders of 30th Battalion had landed on Blue Beach, while 35th and 37th Battalions had come ashore on Green and Red Beaches, respectively. To the invaders’ pleasant surprise, their landings were unopposed.

As Sergeant William Laurence and his men struggled to get their Bofors antiaircraft gun through the surf, he noticed three onlookers in jungle-green uniforms but without insignia. He vigorously suggested that they help pull the gun ashore. The three complied. Later, to Laurence’s surprise, one of the men introduced himself as Brigadier Charles Duff, Royal Artillery, and said that Major General Barrowclough sent his compliments. Laurence then realized that Barrowclough had been another of the trio who had helped out.

In the planning for Squarepeg, Barrowclough had sought a force multiplier in case the Japanese struck back. He decided to land armor—3 NZ Division’s Tank Squadron equipped with Valentine tanks. Eight were landed on Nissan midmorning of D-Day. The Tank Squadron’s Major Arthur Flint recalled that orders were given that the Valentines were to support the infantry in their advance inland. He went 150 yards up a track to reconnoiter. Suddenly, everyone in the vicinity dove for cover because of movement up ahead, and a Japanese attack seemed imminent. “After a minute the ‘sighting’ came down the track and turned out to be a Seabee with a theodolite over his shoulder and busy surveying. We were not sorry.”

The Kiwis were amazed at American ingenuity. Frank Cox, a tank commander, recalled that he saw “one LST, heavily loaded, stuck fast on the beach trying to back off. Bulldozers were tried with no success. A U.S. Navy destroyer was called up which sailed past at full speed creating a huge wash which ran up the beach and back again taking the LST with it.”

Having landed, soldiers and Seabees began the backbreaking task of unloading supplies and equipment. The invaders later dug in for the night. However, there would be no rest; Japanese planes flew over at regular intervals dropping bombs.

The Push Inland

There had been no contact with the Japanese defenders on the first day, but uncertainty remained, and it seemed that they were biding their time. Patrols set out, trekking through the jungle, but still no contact occurred. Where was the enemy?

On 17 February, after a Japanese barge had been sighted on Sirot Island, it was decided to send a small force of infantry to investigate. Artillery pounded the island and then a reinforced company of 30 Battalion landed. To their horror, the Kiwis discovered that the enemy had set up machine guns in the dense jungle and were all but invisible. A firefight erupted with the Japanese fighting to the last man and in the process killing five New Zealanders and wounding three. The 21 defenders had sold their lives dearly.

The next day, 37 Battalion soldiers cleared the northern part of Nissan Island. The lack of Japanese resistance led to a severe misjudgment of enemy strength in the southern part of Nissan, where patrols from 35 and 30 Battalions were close to linking up. While they were clashing with only single or small groups of defenders, on 19 February a Japanese soldier sent a message to Rabaul: “We are charging the enemy and beginning radio silence.” The Kiwis’ patrolling forestalled an organized assault, but the Japanese were determined.

Fight at Tanaheran

The New Zealanders had patrolled through the dense bush near Tanaheran Village without incident when on 20 February Captain J. F. B. Stronach was searching for a suitable spot nearby for 14 Brigade’s headquarters. All seemed quiet until a shot rang out. Thinking they were dealing with an isolated straggler, the men in Stronach’s platoon began to comb the area. To their consternation, intense rifle and machine-gun fire erupted, and two Kiwis quickly were wounded. The fusillade continued, joined by mortar fire, pinning down the soldiers.

Stronach’s liaison with Tank Squadron dispatched a message, and two Valentines made their way to Tanaheran. Arriving at the battlefield, the tankers learned that one soldier had been shot and was either dead or wounded and left where he fell. A plan was devised: Four Vickers machine guns would provide covering fire while the Valentines advanced to recover the casualty.

Although the Japanese at Tanaheran lacked antitank weapons, they had resoluteness in spades. Tanks have vulnerabilities, especially limited vision in close terrain. Snipers began firing at the tanks’ periscopes and destroyed four or five of these, blinding the crews. Vickers machine guns and the Valentines began raking the areas where they thought the Japanese were with bullets and high-explosive shells. A Japanese sniper fatally shot one machine gunner in the head.

Two more Valentines arrived and began firing at the Japanese. A pair of the tanks then recovered the casualty, a wounded soldier. Because of the dense jungle terrain, which rendered tank movement extremely difficult, with the real danger of the vehicles throwing a track and being rendered immobile, the Valentines prudently withdrew.

At 1345 Major A. B. Bullen’s D Company, 30 Battalion, arrived on the scene, relieving Stronach’s platoon as fighting with the virtually invisible Japanese continued. Late in the afternoon, Bullen realized there was nothing left but to launch an assault before nightfall. Three-inch mortars softened up the defenders, and then the infantry went in. The Japanese fought desperately in small groups taking maximum advantage of coral rocks and the jungle. As the New Zealanders advanced, a wounded Japanese soldier placed a grenade on his stomach and committed suicide. A sniper mortally wounded Captain P. R. Adams, and defenders killed four other Kiwis and wounded seven.

Some Japanese managed to escape from Tanaheran and attempted to flee in a canoe. A PT boat intercepted them a mile or two offshore. Two of the Japanese opened fire but were killed by one of the PT boat’s gunners. A third Japanese soldier who was badly injured was captured.

While the fight at Tanaheran had been raging, Admiral Halsey and various high-ranking officers arrived at Nissan’s lagoon by PBY-5A Catalina flying boat. The South Pacific commander conferred with Barrowclough, and having satisfied himself, he and his party left several hours after landing.

Subsequent fighting took place on Pinipel and smaller nearby Sau Island. While organized resistance ended on 23 February, there were still Japanese holdouts; a Kiwi soldier had a shock when a bullet hit two feet away from where he was shaving. Once the Green Islands had been secured, remaining Japanese soldiers had no good options. Surrender was unthinkable (although a few Japanese were captured after being disabled), they could not get off the islands, and the only remaining alternatives were suicide or a slow death from jungle diseases and starvation.

Squarepeg’s Consequences and Costs

The immediate result of seizing the Green Islands was that the supply chain was broken to some 20,000 Japanese soldiers on Bougainville, Choiseul, and Buka Islands, and they were left to surrender or starve. Japanese plans to hold a defensive perimeter and launch strategic counterattacks were frustrated.

New Zealand casualties in Squarepeg amounted to 10 killed and 21 wounded. The American invaders suffered 3 killed and 3 wounded, not including the St. Louis’s losses. For the Allies it was a relatively light casualty rate, but that was no consolation to the wounded and the families of those who were killed. Japanese casualties are hard to estimate; many defenders chose suicide by jumping over cliffs into the sea. An official New Zealand history of the Pacific war puts the number of Japanese killed at 120.

Barrowclough, as the commanding general on the Green Islands, was in the unusual position of being in charge of not only his own soldiers, but also Americans. He exercised this command in such a way that the relationship with the Americans was harmonious. One of them he became acquainted with was a young U.S. Navy lieutenant assigned to South Pacific Combat Air Transport Command—Richard Milhous Nixon, who played chess with Barrowclough during his sojourn on the islands. While Nixon would be elected U.S. President, Barrowclough, after leaving military service, became Chief Justice of New Zealand.

With Nissan secured, Seabees quickly built an airfield, with fighter and bomber runways, and a base for PT boats. Until the end of the war, Rabaul received regular bombing raids from U.S., Australian, and New Zealand air forces. Arguably, the bombing campaign is one of the forgotten instances of interservice and international cooperation.

In endorsing Admiral Wilkinson’s report on Squarepeg, Admiral Halsey stressed how well the Kiwis and Yanks had worked together: “The entire Green operation was thoroughly planned and was executed with the utmost precision and team play. . . . From conception to completion I consider that [it] was a remarkably fine combined operation in every sense of the word.”

The Green Islands became a backwater as the war moved northward. The Kiwis handed over control of them to the Americans on 29–30 May 1944 and were returned to New Zealand. Due to an acute civilian manpower shortage at home, 3 NZ Division was later disbanded.

Today, getting to the Green Islands is difficult, but its people are friendly and welcoming to visitors. The islands have lapsed again into oblivion, but the echoes of the Pacific war still reverberate there.

Sources:

Commander Task Force Thirty-One, War Diary, February 1, 1944 to February 29, 1944, RG 38, National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, MD (hereafter NARA).

Commander Third Amphibious Force, Seizure and Occupation of Green Islands, 15 February to 15 March 1944, RG 38, NARA.

Oliver Gillespie, New Zealand in the Second World War, 1939–1945: The Pacific (Wellington: War History Branch, R. E. Owen, Government Printer, 1952).

Reg Newell, Operation Squarepeg: The Allied Invasion of The Green Islands, February 1944 (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co, 2017).

Henry I. Shaw and Douglas T. Kane, History of Marine Corps Operations in World War II, vol. 2, The Isolation of Rabaul (Washington, DC: Historical Branch, Headquarters, USMC, 1963).

USS Honolulu, War Diary for February 1944, RG 38, NARA.

USS St. Louis, War Diary for February 1944, RG 28, NARA.