In mid-1943, as the Allies advanced up the Solomon Island chain, the tempo of air operations increased with strikes at targets in Japanese-held territory. It was inevitable that Allied aircrews would be forced down behind Japanese lines. After ordeals of fire and water, seven American aircrewmen would find sanctuary on Mono Island in the Treasury Islands group. Their story is an epic of survival, courage—and incredible luck.

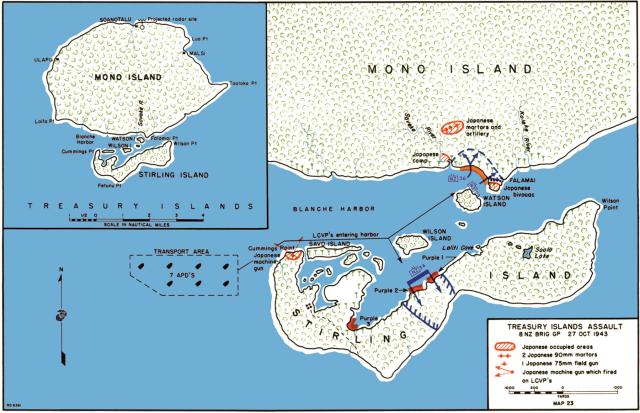

The Treasury Islands group is part of the Solomon Island chain. The two main islands are Mono and Stirling. Mono is mountainous and round, roughly four miles north to south and six miles in an east-to-west direction. Thick jungle covers most of the island. During World War II, it was home to some 150 islanders, with the main village of Falamai in the south. The islanders subsisted on fishing and gardening.

A mile to the south across Blanche Channel is Stirling Island, about three miles long by one mile wide, flat, and covered in dense forest. The Treasury Islands had been the focus of Methodist missionary activity in the prewar period, and the population was staunchly Christian.

The islands had been seized by the Japanese in 1942 and were lightly garrisoned by seven soldiers of the Imperial Japanese Navy Special Landing force, essentially naval infantry. The garrison’s treatment of the islanders varied between elements of benevolence and brutality. Although they did not understand the titanic struggle between Japan and the Allies, the islanders were generally pro-Allied.

Peck’s Men

The first Allied aircrew to wash up on the Treasury Islands were survivors from a downed U.S. Navy TBF Avenger. On 16 June 1943, the plane—piloted by Lieutenant (junior grade) Edward Peck, with Ensigns Jesse Scott and Stanley Tefft as crew—had taken part in a nighttime flare-dropping mission over Kahili. The Avenger’s engine was hit by flak and caught fire. Tefft took a shrapnel hit in his left shin. The plane crash-landed to the south of the Japanese-held Shortland Islands.

The aircrew boarded a rubber raft and began rowing south for Allied-held Vella Lavella. With Tefft suffering immensely from his wound, the wind and waves defeated their efforts, and they decided to try for the Treasury Islands.

En route, the raft attracted the attention of gray sharks, which followed uncomfortably close. Peck whacked one persistent shark on the nose with an oar, and thereafter it stayed out of the oar’s range. On the second night, this shark gave up and went in search of other prey.

When daylight came on 19 June, the aircrew made landfall on a beach on the south side of Stirling Island. They hid their raft. Peck left Scott and Tefft and walked onto a small beach, where he met two islanders. He tried to tell them that he was American, but a misunderstanding arose. A few days previously, a Japanese pilot had crashed in the same area and had been taken by the islanders to the garrison. Likely, the sunburnt Peck looked like an olive-skinned Japanese pilot. The islanders ran off to tell the Japanese garrison of his presence. The Japanese immediately sent out a patrol.

The aircrew had split up and gone exploring. Tefft saw Japanese soldiers and took cover, but he had left a hatchet on the beach, which the Japanese found. Narrowly avoiding capture, he squatted in the jungle for four hours before swimming a mile down the beach and rejoining his comrades. The aircrew decided that being on Stirling was too dangerous—and that they would have a better chance of survival on the larger island of Mono. Late that night, they launched their raft, rowed to a secluded bay on the north side of Mono, and found a cave, where they laid low and rested.

On 24 June, they decided to risk contact. Following a track to Malsi, they came across a group of 30 islanders. Peck warily approached them, his hands held out in peaceful greeting.

To his amazement, he received a “British salute” and greetings of “Good morning.” The islanders took the airmen to a cave and hid them.

Laying Low in Jungle Caves

But the danger had not passed. Orders had been given to 64 Japanese soldiers from Bougainville not to return until they had “disposed” of the man who had been spotted. While one group of islanders kept the search party busy by leading it all over Mono, another group guided the Americans deeper into the interior to a well-hidden cave. After 14 days of fruitless search, the Japanese gave up, with the islanders assuring them that if the Allied pilot turned up they would tell the Japanese.

Taking fearful risks, the islanders moved the aircrew periodically around the island. They provided the fugitives with food, clothing (including a purloined pair of Japanese underpants taken from a washing line), and mosquito nets. The Americans’ uniforms disintegrated in the tropical conditions, and they adopted whatever clothing was given to them. Being in non-military uniform would have provided the Japanese with a reason to execute the Americans as spies if they had needed one.

The Japanese sent another 24-man search party that combed Mono but without success. Then, on 30 June 1943, the Allies took Rendova, and the Japanese reacted by withdrawing all but the seven-man garrison from the Treasury Islands.

The Americans and the islanders came from vastly different worlds, but there was an important basic commonality between the aircrew and their hosts: religion. Christian hymn-singing and religious services banded them together.

Tefft, meanwhile, continued to suffer. A thorn in his right leg had become infected; on 5 July, he became feverish, and movement was difficult. The islanders provided him with their own medicinal remedy, and his condition improved.

More ‘Guests’ Drop In

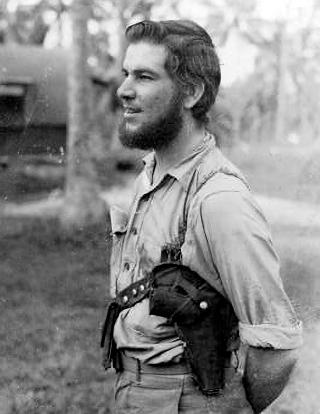

The next American “guest” to arrive was 24-year-old Second Lieutenant Benjamin King of the 339th U.S. Army Air Forces Fighter Squadron—the epitome of an aggressive fighter pilot. On 17 July 1943, King had been flying his P-38 Lightning as fighter escort for U.S. bombers attacking Kahili Harbor at Bougainville. King shot down two Zeros, but other Zeros attacked, damaging his plane’s instruments, wing, and engines. With the aircraft critically damaged, King decided on a water landing.

He landed the plane, which began to sink rapidly as the Zeros made strafing runs. A bullet grazed King’s head. Then the Zeros left, and King discovered to his relief that he had a rubber boat, which he inflated and began rowing in the direction of Mono Island. Four days later, he landed in heavy surf, and islanders helped him ashore. They took him to a house deep in the center of Mono, where he met Peck’s men. He was able to give them the good news: The New Georgia Campaign had begun, and the Allies were only 75 miles away.

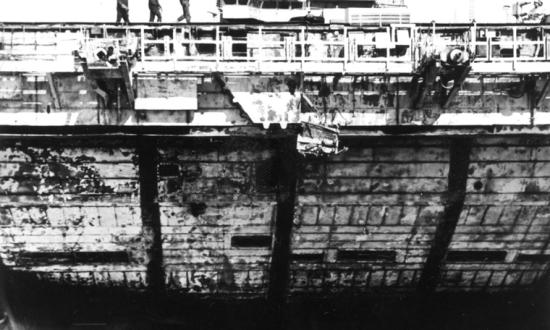

On 18 July, a TBF Avenger crewed by pilot Ensign Joe Mitchell, Aviation Ordnanceman First Class Chauncey Estep, and Aviation Radioman Third Class Dale Dahl of U.S. Navy Escort Scouting Squadron 26 was involved in an attack on Kahili. After dropping his bombs, Mitchell realized the left landing gear had locked into place, slowing his plane down. Attacked by a Japanese fighter, the Avenger’s wings and fuselage were badly shot up. Fuel began leaking profusely, and Estep was wounded in the right thigh.

Mitchell successfully landed the plane on the ocean, and the three crew members clambered into a rubber life raft and began rowing. On the morning of 21 July, the aircrew attempted to land on what they discovered later was Stirling Island, but their raft capsized in the heavy surf. After salvaging what they could and hiding the raft, the men began exploring.

They came across an islander who offered to help them. He rowed across Blanche Channel to Mono and returned with other islanders in canoes. They told the aircrewmen that they would wait until nightfall and then take them to the other Americans on Mono. In the early hours of 23 July, the men were rowed to Mono and united with their fellow countrymen. There was some disappointment on Mitchell’s part, because he had hoped to meet a Coastwatcher, who would facilitate a return to Allied lines.

The increased number of downed aviators placed a strain on the islanders’ resources, but they unstintingly provided food, water, and support. They attended to the wounded, who began to recover.

To Play Safe or to Attempt Escape?

The idea occurred to the seven Americans that they could surprise the garrison, kill the Japanese, steal their launch, and sail to Allied lines. This proposal met with objection from the village chief, Ninamo. He saw that there was a balance of power with seven Japanese and seven Americans. He was acutely aware that the killing of the garrison would have prompted a murderous response from the Japanese. The idea was nixed.

Meanehile, the Americans became divided. Scott and Dahl thought it better to hunker down and wait for rescue. The others wanted to get off the island and try to get to Vella Lavella. They devised a plan to lash the two rubber rafts together and paddle for Allied lines. Straws were drawn for the four positions on the rafts. King, Peck, Mitchell, and Tefft were chosen. They made the attempt on 20 August but were defeated by rough seas and high winds.

Worryingly, Japanese soldiers arrived from the Shortland Islands on 25 August, and the garrison now totaled 150 men. The Japanese began to move across the island in an unpredictable way, and the aviators’ chances of discovery ramped up.

On 13 September, another escape attempt was made. Ferried out into Blanche Channel by the islanders, the Americans boarded their two lashed-together life rafts and began paddling vigorously. They witnessed dogfights in the sky and attracted the attention of a Royal New Zealand Air Force Hudson, which dropped supplies that, unfortunately, could be not recovered.

That night, hearing a lone PBY-5A Catalina, the Americans lit their makeshift kerosene signal lamp, which was spotted by the plane’s pilot, Lieutenant Fred Gage. He circled the raft and dropped flares.

He knew that the adverse sea conditions and limited visibility posed a significant risk to his seaplane. Standing orders required rescue landings to receive the prior approval of the squadron’s commanding officer. Gage radioed for permission—and was told the officer was at the movies.

Gage asked his crew if they should land anyway, and they all agreed. Visibility was poor, and there were swells of five to six feet. Gage skilfully landed the seaplane and taxied to within 150 feet of the rafts. The weary but relieved aviators paddled to the seaplane and clambered aboard. Takeoff was difficult, but the seaplane got airborne.

Gage then received the message from his commander: “You are not to land under any circumstances.” Gage replied: “Sorry, skipper, we have already landed and have the survivors. We are on our way back to Guadalcanal.”

Three Still Stranded

The four rescued men were in relatively good condition, and they provided useful intelligence on the Treasury Islands. They also disclosed the arrangements they had made with the three remaining aircrewmen on Mono for rescue: A “Black Cat” (PBY Catalina) would drop a flare the night before rescue by PT boat, submarine, or seaplane. The trio would light a signal fire at Lua Point to give the all-clear then stand by to be picked up there.

According to plan, on 18 September a flare was dropped, but the Japanese in the vicinity thought they were about to be bombed and took to the jungle. The rescue was thwarted. The islanders kept close watch on the Japanese and moved the trio around. A second flare was dropped on 20 September, and the trio lit a signal fire but got no response. A third flare was dropped on 25 September, but, to the Americans’ anguish, Japanese soldiers were busy installing a telephone line at Lua Point, and rescue was impossible.

On 1 October, the remaining castaways spotted a Catalina, but they were suspicious the Japanese might have captured the the PBY and were flying it as a ruse to draw them out of hiding. The islanders told the trio that a PT boat had been seen on the western side of the island, but the Americans were skeptical, because Lua Point was on the eastern side. Another flare was seen, another signal fire was lit. But then a breathless islander arrived and warned that the Japanese had seen the fire, and a patrol was on its way. The islanders whisked the Americans deeper into the jungle. And as more Japanese reinforcements arrived, the chances of discovery rose exponentially.

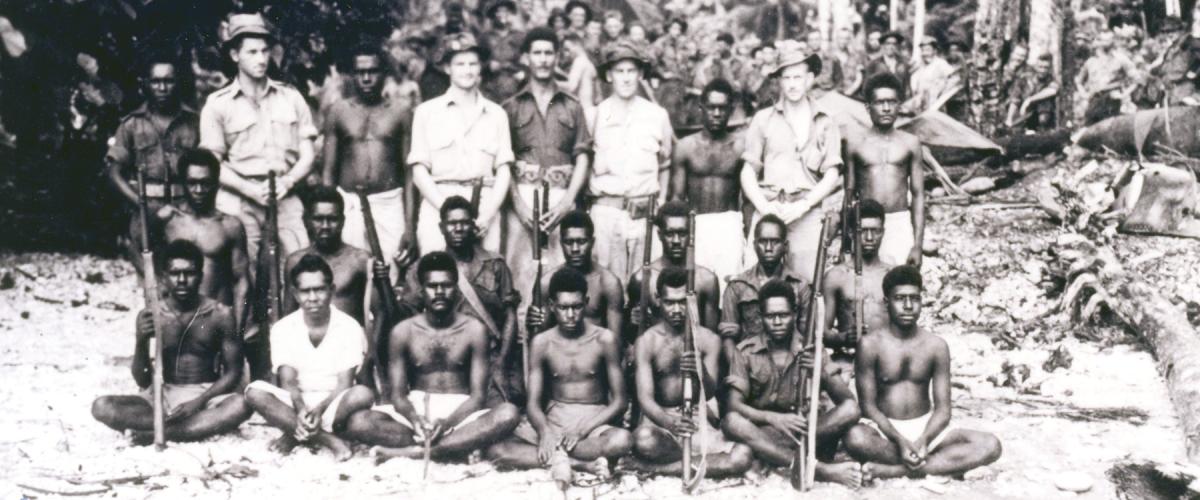

Meanwhile, it had been decided that the Treasury Islands would be seized as a diversionary operation to draw Japanese attention away from the U.S. invasion of Bougainville at Empress Augusta Bay on 1 November 1943. The task of taking the Treasury Islands was given to 8th Brigade, 3rd New Zealand Division, and the date was set for 27 October. Since there was no Coastwatcher on the Treasury Islands, a small reconnaissance party led by Sergeant Bert Cowan, a New Zealand intelligence specialist, was sent in.

With him were U.S. Army Air Forces Corporal Benjamin Franklin Nash, who had inveigled his way into the Coastwatcher organization, and Sergeant David Ilala and Warrant Officer Frank Wickham, both of the British Solomon Islands Defence Force. The plan was to land the party by a large native canoe offloaded from a PT boat. They would spend 24 hours on Mono, carry out investigations, and be picked up by PT boats at midnight.

The PT boat duly delivered the patrol; the canoe surged through the surf and landed with a “bang crash.” The patrol struggled to drag it ashore. At daylight, Cowan made contact with the islanders. He recalled that “they were pleased to see us and gave us breakfast.” They told him about the three stranded Americans. Cowan, whose orders were to gather information and not waste time on the survivors, nonetheless agreed to meet them.

Informed of the party’s landing, Jesse Scott, one of the remaining three, feared a trick and had his pistol ready. The islanders brought Cowan to meet Scott. Now the stranded men were jubilant—but were not yet out of danger.

Liberation Day

Cowan completed his information-gathering mission with aid from the islanders and the three Americans. The patrol laid low during the day, and as midnight approached, preparations were made for extraction.

Cowan’s party got into their canoe and, along with accompanying islanders in their canoes, rowed a mile offshore at midnight. It was pitch black; there was no sign of the PT boats. Cowan dreaded being in open water at daylight. However, his luck held, and contact was made with the PT boats. The group—including the stranded aviators—boarded the boats and headed for the safety of Vella Lavella. They were then flown to Guadalcanal, medically checked, and found to be in good physical condition. They had an intelligence debriefing and provided useful information for the forthcoming invasion.

They also discovered why the repeated rescue attempts had failed: Chauncey Estep noticed that, on the map of the Treasury Islands in the intelligence room, Lua Point was shown on the wrong side of the island. A mistake in mapmaking had placed their lives at risk.

The invasion took place on 27 October 1943 and was successful. Falamai Village was devastated by an explosion of Japanese ammunition stored in the church. Fortunately, the islanders had been tipped off by Sergeant Cowan, who had landed a second time just prior to the invasion. The islanders had fled to the safety of Mono’s caves.

The Treasury Islanders celebrate 27 October in each year as their Liberation Day. Family of the seven aviators have visited and expressed their gratitude for the help given to the stranded Americans. And to this day, an enduring bond exists between the islanders and their guests.

Sources:

Eric Bergerud, Fire in the Sky: The Air War in the South Pacific (New York: Basic Books, 1999).

Bert Cowan interviews with author, 28 August 2001, 10 March 2002, December 2005.

Oliver A. Gillespie, The Pacific: New Zealand in the Second World War (Wellington, NZ: War History Branch, Department of Internal Affairs,1952).

HQ 8 Brigade, “Reports on Treasury Island, Recce to Mono Island, Sgt WA Cowan,” n.d., WAII DAZ151/9/5, Archives New Zealand, Wellington, NZ.

Walter Lord, Lonely Vigil: Coastwatchers of the Solomons (New York: Viking, 1977).

Reg Newell, Operation Goodtime and the Battle of the Treasury Islands, 1943: The World War II Invasion by United States and New Zealand Forces (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2012).

LTJG Edward Peck, USN, “Medical report on Survivors Marooned on a South Pacific Island,” n.d., author’s collection.

“Report of the Occupation of the Treasury Islands, Wilkinson to Nimitz, 10 November 1943,” WAII EA187/19/7, Archives New Zealand, Wellington, NZ.

Jesse Scott correspondence with author, 6 November 2001, 9 February 2002, 11 April 2002, 12 June 2002.

Henry I. Shaw Jr. and Maj Douglas T. Kane, USMC, Isolation of Rabaul: History of the U.S. Marine Corps Operations in World War II, vol. 2 (Washington, DC: Historical Branch, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps, 1963).

ENS Stanley Tefft, USN, correspondence with ENS Jesse Scott, USN, n.d, author’s collection.

Third Division Histories Committee, Headquarters (Wellington, NZ: A. H. & A. W. Reed, 1946).