On 31 January 1944 a group of New Zealand soldiers and Allied specialists carried out a daring reconnaissance of the Japanese-held Green Islands, deep behind enemy lines. The reason for the high-risk venture lay with the overall strategic situation as the year dawned. By late 1943, the forces of Imperial Japan were on the defensive in the Pacific. After victory on Guadalcanal, the Allies had steadily advanced in the Solomon Islands, but the Japanese base at Rabaul on New Britain still menaced Allied progress in the South Pacific.

Operation Cartwheel was designed to neutralize the threat from Rabaul. The Joint Chiefs of Staff wisely had decided not to attack the stronghold directly; a substantial Japanese force was dug into the volcanic rock there and eagerly awaited the chance to repel such an assault. The Allied plan was to encircle Rabaul and neutralize it with air and sea power. This required the seizure of air and naval bases within striking range.

As Commander, South Pacific Area, Admiral William F. Halsey had the main responsibility for dealing with Rabaul. The forces under his command had advanced as far as Bougainville in November 1943. His problem was that he needed to keep the Japanese off balance and to sustain his own pace forward. He intended to take Kavieng, on the northwestern tip of New Ireland, but it required lengthy major preparations that he feared would kill the momentum of the South Pacific drive. So Halsey decided to undertake a lesser invasion. He sought a target within fighter range of Kavieng, with the invading force to be within protective fighter coverage by Allied planes.

To Isles Unknown

The Green Islands fit these requirements and offered the potential to dominate the approaches to Rabaul. Halsey had a further problem, however. Virtually nothing was known about these islands. Feverish efforts were made to get information from missionaries and coastal traders. There was an acute awareness that an amphibious operation required detailed information about tides, Japanese defenses, and beach conditions. Halsey delegated matters to Vice Admiral Theodore S. Wilkinson, an adept practitioner of amphibious warfare. He decided to send a small force of patrol torpedo (PT) boats to the Green Islands to investigate. Nicknamed “the Mosquito Fleet” because of their small size but potent armament, the PT boats seemed ideal for such a covert reconnaissance.

PT-176 and PT-184—supported by two modified gunboats, PT-59 and PT-6—of Motor Torpedo Squadron 11 were chosen to carry out the recon. The boats proceeded under cover of darkness on the night of 10–11 January 1944 but ran into foul weather that damaged the gunboats. Nonetheless, the craft struggled on and entered the southern channel of Nissan Atoll. The crews took soundings and confirmed conditions were satisfactory for a landing. Once he received the report, Wilkinson decided to take matters further.

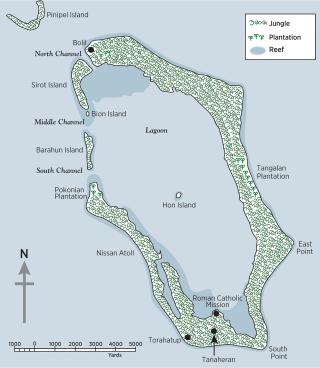

What was known about the Green Islands was that they are located 4 degrees south of the equator and lay 117 miles east of Rabaul. Nissan, the main atoll in the group, is an almost complete oval of solid coral running nine miles north to south and five miles east to west. The atoll is pierced by three access channels leading into the deep inner lagoon. In 1944, the Green Islands had a native population of 1,500, most of whom lived on Nissan. They subsisted on pigs, goats, and chickens, supplemented by fish. A copra plantation had been established in the prewar period, as had a Roman Catholic mission. The one drawback to Nissan was that drinking water was in short supply; the islanders relied on rainwater.

The Japanese had captured the Green Islands on 23 January 1942 and made them an integral part of the barging network supplying their forces on Buka and Bougainville. Because of Allied air and naval attacks on barges, the Japanese crews hid during the day and moved at night. Their wooden Daihatsu-class landing craft generally were kitted out with formidable weaponry. Allied air reconnaissance indicated the Green Islands were garrisoned lightly, but numbers tended to fluctuate as barges visited the islands.

The garrison consisted of soldiers of the Imperial Japanese Navy’s Special Naval Landing Force. While exact numbers were not known, it was acknowledged that Japanese defenders would fight to the death. Worryingly, aerial photos showed a series of new clearings. It seemed the Japanese were up to something.

Enter the Kiwis

Now knowing, thanks to the PT boats, that Nissan was a viable target, Wilkinson ordered more in-depth reconnaissance. A list of specialists in communications, airfield construction, engineering, hydrography, and marine surveys was compiled. These valuable experts needed a protective escort, and the job went to the soldiers of 30 Battalion, 14 Brigade, 3NZ Division.

The New Zealand Army’s 3NZ Division had provided two brigades for the Solomon Islands campaign, which had been involved in eliminating Japanese resistance on Vella Lavella and invading the Treasury Islands in late 1943. Three hundred soldiers from 30 Battalion were chosen to protect the specialists headed for Nissan, and although these troops had been on Vella Lavella, they had not seen combat.

To hide the reconnaissance nature of the incursion, the commander of 3NZ Division, Major General Harold Barrowclough, came up with a plan to disguise it as a “commando raid” with the objective of attacking the Japanese supply barges. He directed that documents be left behind stating that was the purpose of the incursion. The British Commandos had gained an aura of glamour from their raids on Hitler’s Fortress Europe, and the New Zealand soldiers willingly embraced the term “commando” for their operation against the Japanese.

The raid was a combined operation, with U.S. Navy Captain Ralph Earle being in overall command, but with U.S. Navy Commander John McDonald Smith having command of the naval forces, and the commander of 30 Battalion, Lieutenant Colonel Frederick Cornwall, a veteran of Gallipoli and the Western Front of World War I, in charge of the land component.

Planning involved the raiders being transported to Nissan in high-speed transports (APDs), modified troop-carrying destroyers. On their decks they would carry landing craft to be lowered into the water from derricks; the troops then would clamber down cargo nets into the landing craft. The goal was for the raiders to arrive in the early hours of 31 January 1944 and be withdrawn at midnight.

Since the troops would be landing in the dark, NZ 38th Field Park Company built a scale model of Nissan based on aerial photographs. The troops carried out practice landings on the beaches of Vella Lavella, where they were stationed. Emphasis was given to forming defensive perimeters.

Rough Seas, Risky Destination

A transport force of the USS Talbot (APD-7), Waters (APD-8), and Dickerson (APD-21), screened by the destroyers USS Fullam (DD-474), Bennett (DD-473), Guest (DD-472), and Hudson (DD-475), rendezvoused with the soldiers and specialists on Vella Lavella on 29 January 1944. The force set off for the Green Islands, picking up PT-176 and PT-178 off Torokina.

The soldiers whiled away their time playing cards, smoking cigarettes, and checking their equipment. They took turns applying green combat paint to each others’ faces.

Shortly before midnight on 30 January the vessels arrived off the Green Islands. The landing force climbed down cargo nets into landing craft. The sea conditions were rough, and seasickness was rife. The PT boats led the landing craft through the gap between Barahun and Nissan and into the deep waters of the lagoon by Pokonian Plantation. A New Zealand officer, Lieutenant Frank Rennie, later expressed the relief of the soldiers: “It would have been disastrous if we had been fired upon from high ground as the twelve barges went through the gap.”1

Another New Zealand officer, Harry Bioletti, recalled,

There was no communication between the units and it was as black as Egypt’s night. I was down front of the landing craft. When the ramp went down we got off and began digging foxholes in the sand. Then dawn came and we found ourselves surrounded by natives. We asked them if there were any Japs around. The trouble is that they did not understand numbers and the conversation had to be in Pidgin English. They were friendly and we gave them food.2

After offloading the personnel, the APDs headed for the safety of the Allied-held Treasury Islands and protective fighter cover. The raiders were on their own.

‘All Hell Broke Loose’

At first light, using their landing craft, they began their exploration of Nissan Atoll. Two companies crossed the lagoon to Tangalan Plantation on the eastern side. As the vessels surged across the lagoon, the sound of aircraft engines filled the sky and a Royal New Zealand Air Force Ventura came swooping in low, frantically signaling with an Aldis lamp. The raiders could not make out the message. An object with a streamer attached dropped from the aircraft. When recovered, it turned out to be a toilet paper roll. Thinking this was a “a raw joke” played on them, Frank Rennie shook his fist at the fast-disappearing aircraft.3 Rennie was wrong: The air crew had dropped a message warning of five Japanese barges on the south coast. Unfortunately, the message had fallen out of the toilet paper roll.

Meanwhile, a specialist hydrographic team headed by Captain Junius T. Jarman of the U. S. Coast and Geodetic Survey carried out a detailed examination of the middle and south channels and also obtained tidal data. The other exploratory parties checked other sections of the lagoon and the mission station. None of them, so far, had had any encounter with the Japanese garrison.

About a mile south of the Allied beachhead at Pokonian Plantation, however, a party discovered a Japanese barge moored beneath the trees in a small bay. The islanders said there were no Japanese in the area, but Commander Smith made the decision to investigate. He looked at the barge through his binoculars: no sign of life. He ordered the coxswain of his landing craft to approach the barge.

What happened next is described by Lieutenant Robert T. Hartmann, a U.S. Navy public affairs officer who was in the landing craft:

In we went again crouching low. It’s a good thing we were, for the moment our bow hit that quiet little strip of sand all hell broke loose. In considerably less time than it takes to tell, the air filled with lead. Over the side—not ten feet away—was an expertly camouflaged Jap barge. Alongside was another. The Japs—two of those barges would carry about one hundred—had dug themselves pill-boxes in the coral cliffs that rose steeply from the beach behind the hideout. They were in the overhanging trees also. On their first burst of heavy machine gun fire they killed the coxswain. They knocked out both of our bow gunners before they got off a shot. In fact, they hit everybody forward of the motor, except Commander Smith, who was standing without a helmet up by the ramp. He was the only one left who knew how to run the boat!4

Hartmann was amidships, crouched behind an islander. Japanese machine-gun and rifle crossfire poured in from all directions. “Our boat was stuck on the beach and the occupants were dropping like flies.” A New Zealand lieutenant fell wounded. A fresh burst from a machine gun not ten yards off slashed an overhanging branch that crashed down and covered the stern half of the boat. “Through this,” recalled Hartmann, “two of the New Zealanders, with as much guts as I ever hope to see, were pouring fire from their tommy guns back into the inferno.” A Japanese soldier dropped from a tree. The relentless incoming fire was deafening.

Commander Smith was shouting, “Back ’er off—back ’er off!” Then he realized “that nobody was left to back ’er off but himself,” Hartmann recounted. “Cool as a cucumber, he crawled back to the wheel, keeping below the gunwales. He got the thing in reverse after anguished seconds that seemed eternities.” The Japanese kept firing into them, “and no one will ever shake my belief that it was pure miracle that prevented them from killing every soul in that boat.”

The craft finally slipped off the sand and floated. Commander Smith was backing off blind, hoping to dodge myriad coral heads that threatened to render them stuck again. The Japanese continued their furious fire until the boat made it to a couple hundred yards offshore. “We heaved the branch over the side and patched up our wounded as best we could,” wrote Hartmann. “The boat looked like a slaughterhouse. Our boat suffered more than 50 percent casualties and everyone forward of me had been hit.”5

Commander Smith, himself miraculously unhurt, had managed to get her out, but not without a price of three killed, five wounded. Having survived the hail of gunfire, he returned to the headquarters that had been set up at Pokonian and demanded that the Japanese be eliminated. Colonel Cornwall, however, insisted that the reconnaissance missions be completed. Nonetheless, the New Zealanders set up mortars and began lobbing about a hundred rounds at the Japanese barges.

By late afternoon, the reconnaissance missions had been completed and Major A. B. Bullen was ordered to take two platoons and attack the Japanese. He planned to land a platoon on either side of the Japanese barges supported by covering fire from other landing craft. The assaulting troops were armed with the explosive gelignite; the intention was to blow up the barges.

Onslaught from On High

As preparations were getting under way, six Japanese Zeros appeared above, strafing and bombing the Allied landing craft—one of which was stuffed with ammunition. Coxswains revved engines and zigzagged off in all directions. The Zeros peeled off, their wings spitting red tracer bullets spattering the water into miniature geysers and ripping through the flimsy sides of the craft. Frank Rennie recalled:

Back on Pokonian the alarm was given: “Take cover—take cover—air raid.” You could hear the drone of low-flying aircraft coming closer and closer. “Get the hell off the beach with those barges,” roared an American officer to the coxswains . . . and they had the unenviable task of reversing their craft into the lagoon and taking evasive action. You could see the small 50-pound bombs leave the Zeros and fall in a diagonal flight towards the water. Small cascades of water flicked around the barges as the strafing planes passed overhead. You could see the . . . pilots turn their heads to look down on the bunch as they roared by. Two platoons found themselves with Japanese troops in front and strafing Zeros to their rear.6

Return fire may have claimed one of the Zeros; its engine smoking, the plane jettisoned its bombs and was last seen losing altitude. The rest of them departed, much to the relief of the Allies. Mercifully, the casualties were light—one killed, two wounded. Commander Smith and Colonel Cornwall faced a dilemma. Should they stay and hold the atoll, or withdraw as originally planned? They had wounded who needed to be cared for, and there was the likelihood of further Japanese air attacks and the possibility of Japanese counterattacks. They made the decision to withdraw.

As darkness began to fall, the raiders boarded the landing craft and headed for their midnight rendezvous with the APDs. The withdrawal, complicated by a receding tide and pitch darkness, was far from smooth. Sea conditions deteriorated, and the Dickerson pumped oil overboard to quiet the waves. The transfer from the landing craft was hugely difficult, and a U.S. officer was crushed between a landing craft and an APD. Eventually, the embarkation was completed, and the raiders returned to the comparative safety of Vella Lavella.

The casualty list for the raid was one New Zealander and three Americans killed. Three Americans and two native guides were wounded. Among the New Zealand wounded were two who suffered leg and ankle injuries getting in and out of the landing craft and two who were injured in combat. A machine gunner suffered second-degree burns on his hand while firing at the Zeros. The raiders had escaped lightly.

The information gathered about tides, lagoon water depths, and sites for airfields was important in the planning of the 1944 invasion of the Green Islands, Operation Squarepeg. The raiders also resolved the mystery of the beach clearances and stoneworks. An intelligence officer talked to some of the islanders, who explained that this was the work of a local cargo cult that was expecting food and stores to be delivered by a phantom ship.

The raid had one negative aspect: The Japanese reinforced their garrison. Two submarines were sent with troops, but because of a storm, only 77 were able to be landed. They joined the remaining Japanese garrison and waited for the Allies’ next move.

It came on 15 February 1944, with the landing of troops of 3NZ Division for Operation Squarepeg. The landing was unopposed except for Japanese air attacks. The Japanese garrison was isolated. In the days that followed the defenders fought desperately but were eliminated. Allied air and naval facilities went up on the Green Islands, and air and sea power rendered the Japanese forces on Rabaul harmless. As the war moved northward, the Green Islands receded once more into tranquility and obscurity.

1. Frank Rennie, Regular Soldier: A Life in the New Zealand Army (Auckland, NZ: Endeavour Press, 1986), 50.

2. Harry Bioletti, interview with the author, 2006.

3. Archives New Zealand, DA 428/3/2, “Past a Joke,” Official War Correspondent, NZEF, 6 February 1944.

4. Third Division Histories Committee, Pacific Kiwis: Being the Story of the Service in the Pacific of the 30th Battalion, Third Division, Second New Zealand Expeditionary Force (Wellington, NZ: A. W. & A. H. Reed, 1947).

5. Third Division Histories Committee, Pacific Kiwis.

6. Rennie, Regular Soldier, 54.