Piloting his RF-8A Crusader photo reconnaissance plane above the verdant and mountainous landscape of central Laos in May 1964, Navy Lieutenant Charles F. “Chuck” Klusmann had no inkling that his life would soon take a dark and unexpected turn.

The aviator of Light Photographic Squadron 63, flying from the aircraft carrier USS Kitty Hawk (CVA-63) deployed at Yankee Station in the Gulf of Tonkin, was engaged in a super-secret mission. This was a time when few Americans had heard of Laos, sometimes referred to as the “Elephant Kingdom,” or knew where to find it on a map. They were much more familiar with the neighboring territory of Vietnam, the site of a long-running conflict between Communist and non-Communist Vietnamese and their international allies, including the United States. In 1959, the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (North Vietnam) launched an armed struggle to destroy the Republic of Vietnam (South Vietnam) and unite all Vietnamese under Communist Ho Chi Minh’s government. The internationally endorsed Geneva Accords of 1962 had barred foreign military forces from Laos. Nonetheless, North Vietnam deployed troops into the landlocked, lightly populated country and joined with indigenous Communist guerrillas, the Pathet Lao, to oust the Royal Laotian Government in Vientiane. To facilitate its campaign and to arm and supply Communist guerrillas in South Vietnam, Hanoi also began building through the southern “panhandle” of Laos a transportation system, soon dubbed by Americans the “Ho Chi Minh Trail.”

From Simmering Situation to Ramped-Up War

For years, the United States had provided South Vietnam with substantial military, political, and economic assistance to counter Hanoi’s external and internal assault. American military advisers from the armed services, including Army special forces Green Berets and Navy SEALs, did their best to strengthen South Vietnam’s armed forces. Despite this support, southern Communist guerrillas of the People’s Liberation Armed Forces, better known to Americans as the Viet Cong, increased their control of the countryside and began to defeat even first-line combat units of the Army of Vietnam. Political and religious differences, highlighted by the fiery suicide of Buddhist monks in the capital of Saigon, racked the nation. Finally, on 1 November 1963, officers of the South Vietnamese armed forces assassinated President Ngo Dinh Diem, who had ruled since 1955, and put new leaders in positions of power.

By the spring of 1964, the administration of President Lyndon B. Johnson understood that the allied struggle to preserve the independence of the Republic of Vietnam was in deep trouble. Johnson and his civilian and military advisers proposed, as one solution to the problem, threatening North Vietnamese forces in Laos to compel Ho’s government to cease its support for the Communist war effort in South Vietnam. This approach was in keeping with the theoretical concept of “graduated escalation,” then popular with Washington strategists. Hence, if the actions in Laos did not achieve the desired objective of deterring Ho’s government—and they did not—then direct and even stronger actions against North Vietnam itself were promised. It came to pass. As we now know, the Tonkin Gulf Incident of August 1964 and the onset of the Rolling Thunder bombing campaign in March 1965 heralded a significant intensification of the Vietnam War.

Elephant Kingdom Recon

Klusmann’s mission was one of the first actions of Operation Yankee Team, inaugurated on 19 May 1964. U.S. Navy and U.S. Air Force reconnaissance planes, unarmed and unescorted, overflew Laos as a first demonstrative warning to Hanoi to alter its aggressive activities in Indochina. The Laotian government of Prince Souvanna Phouma, under attack by indigenous and external Communist forces, had authorized U.S. reconnaissance planes to enter the country’s airspace. Washington and the U.S. Pacific Command also needed the flights to gather intelligence on North Vietnamese and Pathet Lao activities in the Plain of Jars and east of it to the border with North Vietnam.

So, on the morning of 21 May, Lieutenant Commander Ben Cloud and his wingman, Lieutenant Klusmann, launched from the Kitty Hawk. The two unarmed Crusaders flew 500 miles over the South China Sea and the northern reaches of South Vietnam and entered the air space of central Laos. Klusmann later remembered thinking, “Nothing is going to happen to me [because] we’re invincible. . . . That’s just the way pilots look at things.”1 And, “surely no one would actually shoot at us.” (He did note one item of concern—namely, that it would be difficult for search-and-rescue aircraft to come to their assistance in any emergency.)

The reality of the situation soon banished this wishful thinking. Both aviators noticed white puffs blooming around their planes and red streaks rising from the ground.

They were under fire.

Soon, fuel poured from Klusmann’s left wing and set it ablaze. Both planes ascended to 40,000 feet and headed for the safety of the fleet at sea. The wind and high altitude extinguished the fire on Klusmann’s plane, but pieces of his port wing continued to fly off. The pair made it back safely to the Kitty Hawk, but Klusmann’s aircraft was down to a very low 600 pounds of fuel, and he later found “holes all over” the plane.

Despite this close call, the Yankee Team’s standard operating procedures continued relatively unchanged. Reconnaissance pilots were ordered to fly their aircraft at marginally higher altitudes and at faster speeds, but the missions were still to be carried out low and slow. Higher authority in Washington denied pleas from Commander, Seventh Fleet, Vice Admiral Thomas H. Moorer, for a change in the rules of engagement. From 21 May to 9 June, the U.S. air services carried out more than 130 flights over Laos with no losses—but also no apparent success at changing Hanoi’s behavior.

On the fateful morning of 6 June 1964, Klusmann and his new wingman, Lieutenant Jerry S. Kuechmann, piloted their Crusader recce planes over the jungle along Route 7 between Khang Khay and Ban Ban in central Laos. Because navigational assistance was unavailable to them at this distant location, the pilots relied on map reading and sight to identify their locations and photographic targets. The area had the ominous nickname “Lead Alley,” owing to the heavy concentration there of North Vietnamese antiaircraft weapons.

While making low-level passes (1,500 feet and at a speed of 550 knots) over a suspicious site to get the best photographs, Klusmann’s plane suddenly took hits in a wing and the fuselage. Soon hydraulic fluid poured from the aircraft, disabling the flight controls. As Klusmann related, “After less than two minutes the control system froze and it was time to get out and walk!” The pilot was not injured when he ejected from the plane and his parachute deployed safely.

As Klusmann watched from his aerial perch, the Crusader smashed into the ground and exploded in a ball of fire. Klusmann’s aircraft now had the dubious distinction of being the first of 1,125 Navy and Marine Corps fixed-wing aircraft and helicopters lost to enemy fire and operational accidents in the long, costly Vietnam War.

As he floated helplessly to earth, Klusmann heard and felt bullets fired from the ground zipping past him. Despite efforts to steer clear of the only tree in the center of a clearing, Klusmann’s parachute carried him directly into it. He crashed through the branches, badly wrenching his right hip, knee, and foot. Half-crawling and half-walking, he struggled to find a place to hide. Kuechmann kept his plane overhead as long as he could and put out a Mayday call, but with his fuel almost exhausted, he had to head for the carrier. When a helicopter appeared overhead about an hour later, Klusmann used a handheld mirror to signal the pilot, who revved his engine and rocked his wings to indicate he got the message.

Two fixed-wing aircraft, and later an H-34 Seahorse helicopter—Central Intelligence Agency assets of “Air America”—arrived on the scene.

The quiet hills erupted in furious gunfire as the Pathet Lao guerrillas sprung a trap to shoot the rescue planes from the sky.

Their fire wounded the copilot of one helicopter and put 80 holes in the aircraft. Despite the intense groundfire, the Air America crewmen fired from every open port and even dropped grenades on the troops below.

Klusmann recalled, “These guys had pulled out all the stops and made every possible effort to rescue me.” He realized, however, that the effort to rescue him might cause the death of his fellow Americans and the destruction of their planes. In the words that later would accompany Klusmann being awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross, the Navy pilot, “exhibiting heroism of the highest order, waved off” his would-be rescuers.

Soon afterward, Klusmann chalked up another first in the war—the first American military pilot to be captured and imprisoned by the enemy. By the end of the conflict, hundreds of other U.S. aviation personnel had endured captivity and often torture in the prisons of North Vietnam and the hellish jungle camps of Indochina.

Hemmed in by Bamboo Stakes

As the rescue aircraft pulled out, heavily armed Pathet Lao guerrillas converged on Klusmann, tied his hands behind his back, and put a noose around his neck. Despite these actions, when the guerrillas saw that the pilot could hardly walk, they untied his hands, fashioned a crude walking stick for him, and allowed him to set the pace of their march into the jungle. That night they fed him a meal of rice, cooked greens, and stewed pork. This positive treatment was not always replicated during Klusmann’s subsequent ordeal in confinement.

Following a three-day trek, the party arrived at Xieng Khouang, where he was given a bucket of water with which to clean up but then was put in an “infamous tiger cage” for the night. In the days that followed, Klusmann was taken by truck to a small village on Route 7 near Khang Khay. There, he was presented to the 37-mm antiaircraft crew that had shot him down. He was put on display for the enlightenment and enjoyment of the local populace. He later observed, with his characteristic sense of humor, that since then, “I have never felt comfortable in a zoo” and that “being caged and on display is not” an easy feeling.

That night, the Navy pilot was ushered into the presence of an apparently high-ranking official he believed was the political leader of the Pathet Lao, Prince Souphanouvong, often referred to as the “Red Prince.” One of Klusmann’s fears was that his prison masters would “send me to North Vietnam, and from there maybe to Russia.”

Klusmann was moved again, this time to an off-road site with thatched-roof huts near Khang Khay. In one of the huts, he was placed in solitary confinement in a room with a dirt floor, no windows, and bamboo walls plastered with mud. His furnishings included a bed made of logs and rough boards, a mosquito net, grass mat, blanket, a metal table and chair, a canteen, and a drinking cup. His guard force was billeted in the hut’s two other rooms. The site of his solitary confinement would be his home for the next two months. To keep up his health and to prevent going stir-crazy from the isolation, Klusmann paced back and forth around the room. He estimated that, by the end of his time there, he had walked 183 miles.

Klusmann made an early attempt at escape that did not go well. He tried to dig a hole under a wall only to discover that his guards had implanted bamboo stakes in a trench all around the room to a depth of three feet. He was stymied in this first effort to honor the Code of Conduct, which called for a concerted effort to escape from the enemy.

Interrogated, Indoctrinated—and Defiant

He had a daily routine during the first two months of his captivity. Each morning, two guards, one armed with an automatic weapon, would escort him to the latrine and to a nearby stream to clean himself and brush his teeth. They also brought him morning and evening meals. Those meager repasts usually consisted of a small bowl of rice, boiled greens, and turnip soup flavored by a fiery sauce made with fish, salt, and roasted peppers. He especially disliked the turnip soup because “I never did like turnips [and] I still don’t.” On occasion, the guards would raid nearby caves to snare rats or catch an unlucky stray dog to create a “special” stew and share that bounty with their prisoner. Klusmann understood he had to “eat whatever you can get your hands on or you won’t survive.” Still, his diet was not sufficient for his long-term health. During his captivity his weight dropped from 175 to 125 pounds.

In fact, at one point Klusmann’s health deteriorated dramatically. Bouts of diarrhea became a common occurrence. Smoke from the fires set by his guards in the adjoining rooms caused him to cough excessively and plagued his existence for two months. A serious fever knocked him off his feet for more than two weeks. And the combination of a poor diet and illness caused him severe mental stress and memory loss. His guards gave him some pills and shots with medicines of unknown origin. They did little to help his overall physical or mental condition.

At the meeting with the Red Prince, an English-speaking officer, Captain Boun Kham, had approached the American. The man claimed that he was Laotian but Klusmann suspected he was North Vietnamese. The captain would be his “interrogator and indoctrinator” for many months afterward. He spent a lot of time trying to impress Klusmann with the supposed glories of Marxism-Leninism. To the Navy pilot’s surprise, Boun Kham did not want him to divulge military secrets. Indeed, the officer possessed a book similar to Jane’s All the World’s Aircraft that detailed the characteristics and capabilities of all U.S. combat aircraft. An even greater surprise to the naval aviator was Boun Kham’s possession of the classified organizational manual of the Commander-in-Chief, U.S. Pacific Fleet, which listed the carriers, their onboard squadrons, and their commanders. He even knew precisely when the Kitty Hawk had passed by the Philippines en route to Vietnam that year. This all seemed “a bit incongruous to be sitting in a mud walled hut deep in the jungle [lighted] with a kerosene lantern.”

Boun Kham’s major objective, however, was not to gather operational or tactical intelligence but to use the Navy pilot for political purposes. In long nightly sessions, he repeatedly told Klusmann that all the world thought the pilot had been killed in action. Boun Kham urged Klusmann to make a radio broadcast telling everyone that he was alive and being treated well by his captors. Klusmann told the captain that it would be a cold day in hell before he did as the man suggested. The captain did not ask him again to make a radio broadcast. Unlike North Vietnamese interrogators during the war, this Pathet Lao interrogator did not subject his American POW to physical torture.

Instead, Boun Kham switched tactics and urged Klusmann to write a letter to Prince Souphanouvong begging for the pilot’s release from captivity. Klusmann refused. But later, when his prisoner was debilitated from fever, malnutrition, and forced isolation, the captain dictated a letter for Klusmann’s signature. As Klusmann later recounted, “I was in a pretty poor state both physically and mentally and wrote the letter that he told me to write.” When Klusmann recovered from his illness with all his faculties, it hit him like a “bucket of cold water” that “I had done something I should not have done.” He then made up his mind to escape or die trying. Boun Kham, having accomplished his primary purpose, moved on to other assignments.

Unexpected Laotian Allies

The authorities then transported Klusmann to a nearby prison compound. The pilot knew exactly where he was since he had earlier flown over the site and photographed it. The building to which he was confined was surrounded by building-high barbed wire fences reinforced with concertina wire. A group of 35 men, some captured Royal Laotian Army soldiers and former Pathet Lao guerrillas who had run afoul of the movement, soon joined the American at the site.

With only one of the men somewhat conversant in English, communication was difficult. Nonetheless, one of the Laotians approached Klusmann about planning an escape. Once he gained confidence that some of his fellow prisoners were not enemy plants and genuinely wanted to make it back to friendly lines, Klusmann joined in the effort.

The guards periodically allowed the men to wash their clothes at a nearby stream and hang their wet clothes on the fence. Over time, Klusmann and some of the other POWs loosened the nails holding up the fencing behind the drying clothes. Klusmann and one prisoner, Boun Mi, grew to trust one another, and they decided to stick together once they got out of the compound. They each prepared a set of dark clothes to help conceal them as they moved through the countryside.

Finally, one dark, rainy night, when their guard sheltered from the rain in his small hut, Klusmann, Boun Mi, and two other men made their move. They crawled under the loosened wire and silently made their way across 200 feet of open ground to reach cover. One of the men then decided to wait for two others to join him. Klusmann later learned that the Pathet Lao had captured and executed at least two of the prisoners who had stayed behind.

Deciding to put distance between them and the camp before the guard force learned of their escape, the trio headed into the jungle and made for the mountains. After a night on the move and descent into a valley, the escapees crossed a road and hid out in the bush.

One of the men decided to try to obtain food in a nearby farmhouse. Klusmann and Boun Mi remained hidden and watched to see what would happen. To their shock, they witnessed their companion emerging from the structure with his hands tied behind his back and under guard. These guerrillas headed for Klusmann’s and Boun Mi’s hiding spot, which immediately prompted them to high-tail it into the forest.

Escape Through the Jungle

Despite being chased and shot at, after a time the two men eluded their pursuers. Rather than risk their own capture and probable execution, the pair foraged for food at abandoned farms, where they collected bamboo shoots, cornstalks, and sweet potatoes and gathered in the forest some fruit and wild berries. Wisely or not, to ward off the chill of the night and heavy rainfalls, the men started small fires.

Their desperate 25-mile hike through the jungled and mountainous Laotian hinterland soon became “pure drudgery” that thoroughly taxed their physical strength and mental resolve. Bloodsucking leeches that clung to their bodies were a special torment. Finally, after three and one-half days, the pair heard men speaking Laotian in a small roadside guard shack. Remembering what had happened to their unlucky comrade, Klusmann wanted to move away from the site. Boun Mi, however, expressed confidence that the speakers were not Pathet Lao. When he approached the guard shack, armed men came out, but their initial wariness was soon replaced by smiles and back slaps. Klusmann and Boun Mi were indeed now in friendly hands. They had reached an outpost of the village of Baum Long, site of an airstrip used by Air America and guarded by non-Communist Laotian forces. Word of Klusmann’s arrival was immediately telegraphed to U.S. civilian and military authorities in the region. One hour later, a small fixed-wing plane put down at the airstrip, and the Americans on board joyously greeted their long-lost compatriot.

‘First In, and the First Out’

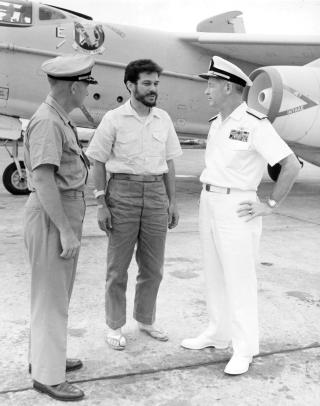

Following Klusmann’s return to friendly lines on 31 August 1964, U.S. military aircraft flew him to the U.S. Air Force base in Udorn, Thailand, and then out to Task Force 77 in the Gulf of Tonkin. There, Admiral Ulysses S. G. Sharp, Commander-in-Chief, Pacific, and Vice Admiral Roy L. Johnson, Commander, Seventh Fleet, learned firsthand of Klusmann’s then-unique wartime experience.

As he later observed, he had been the “first in, and the first out”: the first naval aviator shot down in the war and the first (and only one of two) to escape captivity. He learned, however, that during his captivity, another naval aviator, Lieutenant (j.g.) Everett Alvarez, had been shot down and imprisoned in North Vietnam, where he would spend the next eight and a half years in captivity.

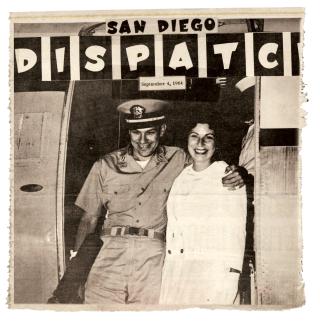

Klusmann was then flown to San Diego, California, where on 4 September he had a joyful reunion with his wife. News of Klusmann’s shootdown, three-month imprisonment by the Pathet Lao, dramatic escape, and return to freedom made headlines all over the United States. The Los Angeles Times and other national and local media outlets featured his story.

Charles “Chuck” Klusmann was happy to tell his story and share in the joy of his survival and escape, but he was a career naval officer, and he wanted to get back to work. During the next 16 years, he served as a test pilot, executive officer, and commanding officer of training commands at naval stations in California, Texas, and the Philippines. To hone his professional skills, he attended the Naval Postgraduate School and the Naval War College. Before Captain Klusmann retired from the Navy on 1 October 1980, he served as Commander ,Mine Warfare Command, Charleston, South Carolina.

Appropriately, he then settled with his wife in Pensacola, Florida—where in 1955 he had been commissioned an ensign in the U.S. Navy and presented his wings as a naval aviator.

1. Chuck Klusmann, “The Price of Freedom,” Klusmann Collection, National Naval Aviation Museum, Pensacola, FL, vfp62.com/IMAGES/Price_of_Freedom.pdf. The information in this article has been derived from “The Price of Freedom,” in addition to the following sources: Rob Johnson, “A Pensacolian’s Escape from Laos,” Pensacola News Journal, 30 August 2014; Station HYPO, “Remembering the Gulf of Tonkin Incident, and Honoring the First POW of Vietnam, CAPT Klusmann, USN,” stationhypo.com/2016/08/02; “Lieutenant Klusmann-Narrative,” Klusmann Collection, National Naval Aviation Museum, unpublished narrative; Veteran Tributes: Charles F. Klusmann, https://veterantributes.org; Edward J. Marolda, Admirals Under Fire: The US Navy and the Vietnam War (Lubbock: Texas Tech University Press, 2021); and Edward J. Marolda and Oscar P. Fitzgerald, From Military Assistance to Combat, 1959–1965, in the series The United States Navy and the Vietnam Conflict (Washington, DC: Naval Historical Center, 1986). I would especially like to thank my colleague and friend, Hill Goodspeed, of the National Naval Aviation Museum, for his helpful assistance on the Klusmann story.