War Comes to the Philippines

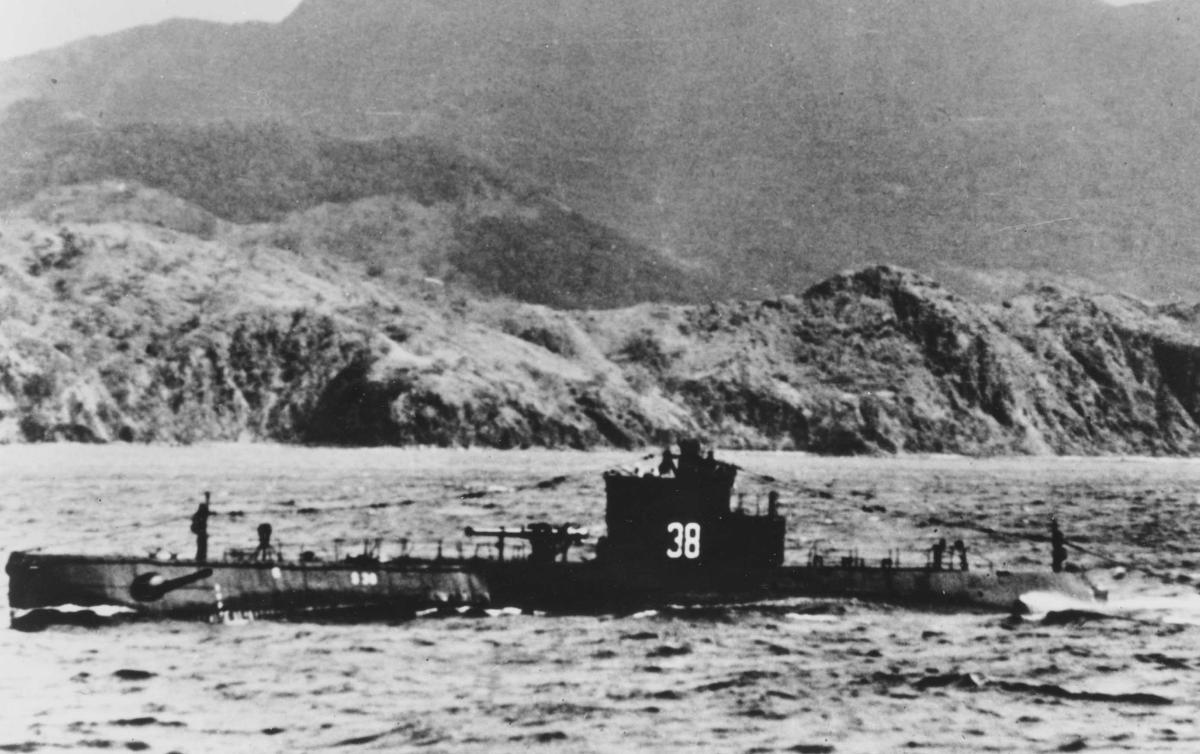

Long before sunrise in the Philippines on 8 December 1941, news arrived that Pearl Harbor had been attacked. The submarines of the U.S. Asiatic Fleet, based in Manila, quickly topped off with fuel, food, and torpedoes. Skippers were briefed, and boats began to sortie enroute to their patrol areas. The USS S-38 (SS-143), an S-class submarine designed at the end of the Great War and lacking the range, firepower, endurance, and habitability of newer fleet-type boats, was among the first underway. She had a crew of 4 officers and 42 men, under the command of Lieutenant Wreford G. “Moon” Chapple.

The gregarious and popular Chapple had more than four years of submarine experience in the Far East, having served on the S-38 from 1933 to 1935 and on the USS Perch (SS-176) and the USS Tarpon (SS-175) from 1939 to 1940 before returning to the S-38 as commanding officer. S-boat skippers were young lieutenants, and S-boat command was considered a learning experience and important steppingstone to command of larger and more capable fleet boats.

Prewar plans for the Asiatic Fleet submarines were to send about a third of the fleet boats to operate off Formosa, Hainan Island, and Indochina, to attack and report on Japanese warships. The U.S. declaration of war following Pearl Harbor brought the decision to conduct unrestricted submarine warfare against Japanese shipping as well, a decision that had been percolating for months but had not been adequately addressed in the peacetime training regimen.1

Another third of the boats would be deployed to defensive patrol areas around the east, west, and northern coasts of Luzon. The rest initially were to be held in reserve, where they could be rapidly directed to any area threatened by Japanese operations. As part of this latter group, four S-boats and the USS Shark (SS-174) and Tarpon were deployed to “standby stations” in the interisland area south of Luzon.2 The S-38 had orders to patrol the Verde Island Passage between southwest Luzon and Mindoro Island.

The S-38’s patrolling was largely uneventful. Her crew had sighted several merchant vessels, all friendly or neutral.3 The boat no doubt had been informed of the Japanese landings in northern Luzon on the 10th, as well as the devastating bombing of the Cavite Navy Yard in Manila the same day. On the 11th, the radiomen likely would have copied a message sent by Commander Submarines, U.S. Asiatic Fleet, notifying the boats of possible enemy forces in nearby Tayabas Bay, directing other nearby submarines to investigate and attack.4 As it turned out, the report was incorrect, but it indicates how rattled the Americans were and the type of information and misinformation the submariners had to sift through as they coped with the sudden transition from peacetime to war.

USS S-38, 12 December 1941

On the evening of 12 December, the S-38 glided on the surface of the Calavite Passage, just northwest of Mindoro Island. Chapple described in his patrol report the events that followed:

2145 Secured battery charge on sighting unlighted vessel lying to.

2223 Fired one torpedo at vessel which was lying to. Torpedo course 287.

2225 Heard explosion and saw large high column of black smoke from vessel.

2229 Vessel had sunk. Dived and listened for propeller noises.

2239 Surfaced.5

Chapple and his crew would have little opportunity to reflect on the event. Little more than a week later, the S-38 was one of several submarines ordered to penetrate Lingayen Gulf to oppose the main landings of General Masaharu Homma’s 14th Army. The S-38 was the only one to accomplish the task. After sneaking past escorts outside the gulf, on 22 December she attacked several transports, claiming a hit on one. In retribution, the boat was hounded by escort vessels and aircraft over the next two days, but she was able to slip past the escorts to return to Manila. Chapple would claim two sinkings: the unlighted vessel off Mindoro Island and the transport in Lingayen Gulf.

There was no doubt of the S-38’s second victim. Japanese records confirmed that the 5,500-ton transport Hayo Maru was sunk by torpedo inside Lingayen Gulf. Of the attack on 12 December, however, findings of the Joint Army-Navy Assessment Committee (JANAC)—commissioned to evaluate Japanese naval and merchant shipping losses during World War II against claims by Allied forces—did not correlate Chapple’s claimed sinking with any Japanese vessel. More than 25 years later, historian Clay Blair wrote in his book Silent Victory: The U.S. Submarine War Against Japan that “no Japanese ships were in the area at that time. If Moon did, in fact, sink a ship, it must have been friendly.”6 So, what had happened?

D/S Hydra II, 2–12 December 1941

The cargo ship Hydra II, operated by Bruusgaard, Kiøsterud & Co. of Drammen, Norway, was not much bigger—and not much older—than the S-38. The master of the vessel was Captain Lars Røed, a 48-year-old veteran mariner, and he had a crew of five Norwegian officers and 44 Chinese seamen. The Hydra II hauled cargo throughout east Asian waters, primarily between Singapore, Bangkok, and Hong Kong.

On 2 December, the shipping company directed Røed to delay his departure from Bangkok while the Norwegian Consulate evaluated the strategic situation in the Far East. The next day, the ship was cleared to depart for Hong Kong, getting underway with a cargo of 2,000 tons of rice and salt. With a cruising speed of nine knots, normal voyage time for the 1,900 nautical mile trip was nine days.

The news that Japan had initiated hostilities was received by radio on 8 December while the ship was steaming northward in the South China Sea about 100 miles off the coast of Indochina. After consulting with his officers, Røed decided to abort the transit to Hong Kong. They would try for the safety of the southern Philippine port of Iloilo.

On the afternoon of the 11th, after passing north of Palawan Island, the ship was stopped in the Sulu Sea by two southbound Royal Navy destroyers, almost certainly HMS Thanet and Scout.7 The British boarding party met with the captain, suggesting the ship could obtain provisions and safe haven at Manila, where they could decide what to do next. Captain Røed thereupon abandoned his plan to proceed to nearby Iloilo; however, the track to Manila would have meant arriving in darkness on the night of 12–13 December. In view of what likely would be jumpy Americans and the minefields in the bay, he devised a new plan. He proceeded north and stopped engines after dark off Cape Calavite on the northwest coast of Mindoro Island. The darkened vessel drifted silently a few miles offshore. He ordered a sharp watch of officers and crew, swung out lifeboats on their davits in the event of an emergency, and planned to begin the transit to Manila Bay around 0400, so they could arrive just after daylight on the 13th.8

Fateful Encounter

Once the surfaced S-38 sighted the darkened vessel off Cape Calavite, Chapple and crew manned battle stations to approach and investigate. They rapidly determined the vessel was not making way. As they closed, the next task would have been to identify the contact to classify it as an enemy target or not. It would have been a dark night, as moonrise did not occur until after midnight. Chapple stated in his war patrol report that he classified the vessel as an “enemy auxiliary appearing to be of Magamo class.” The S-38 was positioned inshore of the target, and Chapple steered a westerly course as he drove into the launch point. At 1,500 yards, the S-38 launched a single Mk 10 torpedo with a zero-gyro angle on course 287.9

On board the Hydra II, Second Mate Alfon Hubert Tidemann was on the bridge with Second Engineer Gunnar Sanne. Tidemann noticed a white streak on the surface of the water headed for the ship’s starboard side. There was little time for warning before the torpedo slammed into the ship just forward of amidships. The blast destroyed the bridge awning, the chart room, and the wheelhouse, and the ship began to settle almost immediately. The six Norwegian officers all went to a lifeboat, but all the axes and other equipment placed to rapidly launch the boat had been scattered by the explosion. Tidemann later reported the ship sank “in 1 to 2 minutes,” so quickly that the davits capsized the lifeboat as the ship was sinking, tossing the officers into the water. Tidemann, Sanne, Third Engineer Georg Emil Hansen, and several of the crew managed to cling to wreckage. But Captain Røed, the first mate, first engineer, and 38 of the crew were lost.

Nine survivors drifted until the Swedish motor vessel Colombia spotted them around noon the following day. The ship reached Fremantle, Australia, on 24 December.

The officers then traveled to Sydney, where the Norwegian Consul General held an inquiry on 25 January. Tidemann submitted a written report dated 13 January 1942, attested to by the two other officers. The second mate’s report indicated they did not believe the vessel was torpedoed by a Japanese ship, as the Hydra II was close to shore and the torpedo was sighted approaching from inshore rather than from seaward. The crew of the Colombia had informed the officers they had seen “many small American torpedo boats” in the interisland waters and offered that perhaps one of them had mistakenly torpedoed the Norwegian freighter. With completion of the inquiry, this encounter between a U.S. submarine and an allied merchant ship only four days into the war faded into obscurity.

Loose Ends

One mystery is Chapple’s classification of the target. No trace can be found of a Magamo-class ship in the Imperial Japanese Navy or among chartered Army vessels. If it was a typo in the war patrol report, a review of other possible ship names failed to provide any potential answers. It is unknown whether Chapple had any doubt as to the classification. It is known that he had seen nothing but friendly merchantmen and a few friendly warships in his four days at sea. Did the previous day’s warnings of potential enemy landings in Tayabas Bay, only 60 miles to the east, make Chapple more inclined to trust his classification? Or was he influenced by the fact that the Japanese had landed on northern Luzon on the 10th, and on eastern Luzon at Legaspi early on the 12th?10

Chapple never ceased insisting he had sunk a Japanese ship that night.11 He always thought he and his crew had claimed the second enemy ship of the war sunk by a U.S. submarine, following a sinking on 9 December claimed by Lieutenant Commander Chester C. Smith and the USS Swordfish (SS-193). As it turns out, Smith’s claim also was not validated by JANAC, so the S-38 was in fact the first U.S. submarine of the war to achieve a sinking. Unfortunately, it was not an enemy vessel.

It is not clear when it became public knowledge that the S-38’s victim was a friendly vessel. John D. Alden’s 1989 book describing U.S. and allied submarine attacks during the war did not indicate the results of the S-38’s 12 December attack. By the fourth edition in 2009, he wrote that the Hydra II was the S-38’s victim.12

While there is little doubt the S-38 sank the Hydra II that fateful night, there are some inconsistencies. Tidemann’s report indicated the Hydra II was proceeding at slow speed about 30 miles from Manila at 2000 on 12 December, and that at 2100 they stopped and were drifting “outside a small light at the entrance to Manila.” Other sources have taken this to indicate the ship was only two miles off Manila Bay. But Cape Calavite with its light is about 45 miles south of the entrance to the bay. With a nine-knot speed of advance, Captain Røed’s intended transit beginning at 0400 to arrive at the bay after daylight would confirm that the ship was off Cape Calavite and not just outside Manila Bay.

In another inconsistency, Chapple wrote that his target was five to seven miles off Cape Calavite, while the Hydra II’s officers stated they were two miles offshore and drifting. In addition, some of the reported times for the attack vary by up to 30 minutes. However, given the excitement, trauma, and passage of time, these minor spatial and time variations can be accepted given the otherwise overwhelming evidence.

Chapple would go on to command the USS Permit (SS-178) and Bream (SS-243) and made more World War II submarine war patrols in command than any other American skipper—11 in total.13 Rear Admiral Chapple passed away in 1991. The Hydra II’s senior survivor, Alfon Tidemann, would serve on other Norwegian-flagged vessels in World War II and passed away in 1999. It is unknown whether the two men were ever aware of their connection.

Prussian military theorist Carl von Clausewitz wrote that “war is the realm of chance.”14 The tragic tale of the S-38 and the Hydra II is another case which proves he was right.

1. For more on the decision to implement unrestricted submarine warfare against Japan, see Joel Holwitt’s Execute Against Japan (College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press, 2009).

2. John E. Wilkes, War Activities Submarines, U.S. Asiatic Fleet December 1, 1941–April 1, 1942 (National Archives, RG38), 3–4. The “Wilkes Report” is a trove of details on the activities of Asiatic Fleet submarines in the opening months of the war.

3. Wreford G. Chapple, War Patrol, USS S-38, dated 30 January 1942 (National Archives, RG 38), A1–3.

4. Louis Shane, USS Shark – Report of Operations during Period 9-21 December 1941 (National Archives, RG 38), 1. See also Lewis Wallace, Patrol Report, USS Tarpon, dated 22 January 1942 (National Archives, RG 38), 2. Both the Shark and the Tarpon’s war patrol reports indicate the message was garbled, listing the location as “Tabayas Bay,” which likely was meant to be Tayabas Bay, which was near the patrol areas for both these boats.

5. Chapple, War Patrol, USS S-38, A2.

6. See Theodore Roscoe, U.S. Submarine Operations in World War II (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1949), 34; and Clay Blair Jr., Silent Victory: The U.S. Submarine War Against Japan (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott Company, 1975), 138.

7. The S-38 sighted and classified two “English destroyers” at 0805 that morning as she patrolled the Verde Island Passage just south of Manila. See Chapple, War Patrol, USS S-38, A2. These could only have been HMS Thanet and the HMS Scout. They had departed Hong Kong after dark on 8 December and stopped briefly in Manila before heading south for Singapore.

8. Information concerning what happened to the Hydra II from the perspective of her crew can be found in several excellent Norwegian online sites (with options for English translation).

9. Chapple, War Patrol, USS S-38, A9.

10. James W. Coe. Brief Summary of USS S-39 War Patrol Report dated 21 December 1941 (National Archives, RG 38). On 11 December, the S-39 had visually detected vessels of the Japanese Fourth Surprise Attack Force (and reported depth charges dropped) enroute to landings in Albay Gulf on the morning of 12 December at Legaspi on the southeast coast of Luzon. Had she reported the contacts—which cannot be confirmed from records—other boats would have been made aware of the incursion. This also might have contributed to Commander Submarines, U.S. Asiatic Fleet’s message later on the 11th concerning enemy landings in Tayabas Bay.

11. Clay Blair interview with RADM W. G. Chapple, USN (Ret), 22 June 1971. Clay Blair Collection, American Heritage Center, Cheyenne, Wyoming Box 67, Folder 1, 7.

12. John D. Alden, U.S. Submarine Attacks During World War II: Including Allied Attacks in the Pacific Theater (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1989), 1. See also John D. Alden and Craig R. McDonald, United States and Allied Submarine Successes in the Pacific and Far East During World War II, 4th ed. (Jefferson, NC: McFarland and Company, Publishers, 2009), 27.

13. S-38 file, Saint Marys Submarine Museum, Saint Marys, GA.

14. Carl von Clausewitz, On War, ed. and trans. Michael Howard and Peter Paret (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1976), 101.