Samuel Pepys, the son of a tailor, rose to become the most senior naval administrator in the British Admiralty during the last decades of the 17th century. His writings reveal a proud man who would be delighted to find he was still famous more than 300 years after his death. His popularity is owed in large part to a private diary he kept for less than ten years, but his crowning achievement was masterminding reform of the Royal Navy, principally through the professionalization of its officer corps.

Pepys early career was at the Navy Board, where he gained firsthand knowledge of the complexities of building, maintaining, and operating warships. Just as today, ships were weapon platforms that required teams of specialists to keep them functioning: boatswains and sailmakers to maintain miles of rigging and acres of canvas; armorers and gunners to keep the cannon batteries operational; and pursers and coopers to ensure hundreds of crewmen could be fed, clothed, and watered for months at sea. Sailing masters applied mathematical skills to navigate the ships safely. But then the ships were placed in the charge of commissioned officers who frequently had little practical experience—and often no desire to learn.

For Pepys, class was the root of the problem. Society at the time was highly stratified, and although there was a growing professional class of lawyers, physicians, and merchants, the officer corps of both the Army and Navy drew largely from the gentry. The widely accepted role of a gentleman was to lead troops into battle on behalf of his sovereign, and performing this duty underpinned his place in society. But any association with trade or the pursuit of a profession could taint a person’s status as a gentleman. Pepys’ concern was that “the gentlemen are not sailors, and the sailors are not gentlemen.”

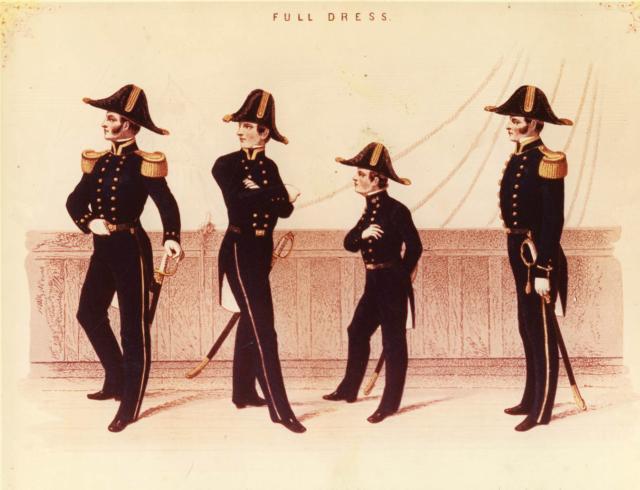

A solution of sorts had grown organically from Tudor times, which was to have two classes of officer. The ship’s professional sailors were warrant officers—boatswain, gunner, carpenter, ship’s master, et al. They were responsible for getting the ship to the scene of battle in a fit state to fight. Once there, the captain and commissioned officers would take over to lead the crew in action.

This worked after a fashion, but it became increasingly untenable as warships became more and more sophisticated. Pepys’ papers reveal his concerns that there were too many “ignorant and idle” lieutenants who had obtained commissions through “families of interest at court.” He feared for the future when “the few commanders (for God knows there are but few) that are now surviving of the true breed shall be worn out.” Pepys was determined to develop professional officers to take their place, men both sailors and gentlemen.

The first steps in reform predated Pepys’ 1673 move to the Admiralty. In 1668, half-pay was introduced for commissioned officers not on active service. This meant that when the country was at peace, officers would be available for future call-up. Along with compensation schemes for officers killed or wounded at sea, these steps made a long-term naval career accessible for those without private means.

Pepys built on this to further reform the profession. At an Admiralty Board meeting, he pointed out that the Navy Board gave sailing masters a formal examination in navigation and seamanship. Pepys proposed a similar examination for candidates wishing to become lieutenants, the lowest commissioned officer rank. To modern eyes, this seems eminently sensible, but to ask gentlemen officers to pass an exam was a startling concept at the time. It would be almost a century before other navies introduced similar examinations; the British Army did not do so until well into the 19th century.

The minutes of the meeting show the idea provoked considerable debate, but Pepys had prepared the ground well. King Charles II and his brother James, Duke of York—both keen naval reformers—attended the meeting to support Pepys. Indeed, some naval historians have speculated that the royal brothers may have been behind the idea. In any event, the upshot was that the board instructed Pepys to turn it into something concrete.

Pepys used the introduction of the lieutenant’s exam to introduce his truly revolutionary idea. This was officer training to be delivered through practical experience gained when the future gentlemen were children. He achieved this by imposing preconditions before a person was eligible to sit for the lieutenant’s exam: The candidate had to be at least 20 years old, have certificates of competence from all previous commanders, and have accumulated three years of sea time, of which a minimum of one year must have been spent as a midshipman.

These seemed reasonable reforms, but their effect was to introduce the apprenticeship Pepys wanted. Because ships in the 17th century generally spent half their time in port (they did not operate in winter, for example), three years of sea time effectively meant six or seven years in the Navy. To accumulate this by the age of 20 meant beginning at 13, the age at which most apprenticeships on land started. The year as a midshipman helped to define the role further.

Before the reforms, “midshipman” was a nebulous rank that permitted willing gentlemen volunteers who lacked a naval commission to serve on ships. Under Pepys, it became an officer training rank, in which promising youngsters learned the practical skills of navigation and seamanship.

Pepys did not get everything his own way. His original proposal suggested that Trinity House (the organization that, among other things, conducted the sailing masters’ examination) perform the lieutenants’ exam. But the idea of commoners sitting in judgment over gentlemen proved too radical for the Admiralty, which instead established panels of three senior naval captains. This inevitably led to at least some patronage and nepotism, as when the young Midshipman Horatio Nelson sat for his exam in 1777. Although he had certainly demonstrated his competence to that point, the fact that the senior examining captain was his uncle, Maurice Suckling, meant Nelson’s age was not enquired into too carefully. He was only 18 and a half at the time.

The stipulation that officers first serve as midshipmen also proved controversial, but here Pepys was determined to have his way. He used his influence to see that the decision was handed to a group of captains that included several veteran commanders from the Anglo-Dutch wars, including Captain George Legge, the future Lord Dartmouth. When Legge was asked if he had spent any time as a midshipman, he replied, “No, and it has cost me many an aching head and heart since to make up the want of it.” Compelling gentlemen volunteers to serve as midshipmen, he added, would “unite the officers and destroy the distinction between gentlemen and tarpaulins [i.e., seamen].” Pepys could hardly have received better support, and the measure was approved. From 1677 onward, no lieutenant could be commissioned in the Royal Navy without first learning his trade, then passing an examination.

The effect of these reforms was gradual at first, with only two lieutenants passing the new exam in the first year of operation, but slowly and surely something remarkable began to take place in the Royal Navy officer corps. As the 18th century progressed, a gulf began to grow between the professionalism of British naval officers and those of their principal opponents in France and Spain. Slowly, competence became more highly valued in the service than notions of class and background.

France’s Pacific explorers were all aristocrats, unlike, for example, the supremely able Captain James Cook, who started his career as a deckhand on a collier. And it is hard to imagine the Spanish Navy employing Captain John Perkins, a black officer from Jamaica who was probably born a slave. Of course, privilege and patronage still counted for much, but even with an influential family, an officer still had to serve his apprenticeship and sit for his exam. Some incompetent officers did manage to slip through, but they were a tiny minority. The growth of this meritocracy reached its zenith in the “band of brothers” that coalesced around Nelson, every one of whom was both a sailor and a gentleman. Pepys would have been delighted.