Beirut, or Berytus as it was first known, was first recorded in the 15th century BC in the archives of ancient Egypt. For 35 centuries the “Pearl of the Mediterranean” and its perfect port have been at the crossroads of civilization. From antiquity to the present, Beirut has had a significant presence on the world stage as a key geopolitical player.

Its history is one of near-ceaseless conflicts between strong and weak, the wealthy and poor, and power-brokering among religious clerics. It has been a vessel of cultural evolution as well as a cauldron in which misunderstandings and mistrust have been fomented by generations of Phoenicians, Greeks, Israelis, Syrians, Jews, Christians, and Muslims.

In the context of Beirut’s long history, U.S. involvement there since the late 20th century is a mere blink of the eye.

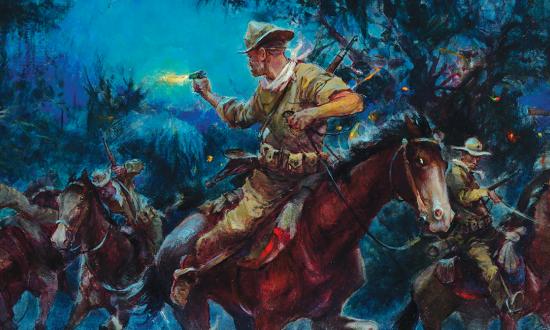

U.S. Marines went ashore in August 1982, just as they had during their first landing in 1958. Both deployments were in response to a civil war between Christians and Muslims. In 1958, Muslims saw the 1,700 Marines storming the beaches as enemies sent to keep President Camille Nemr Chamoun in office, contrary to Lebanese law. The reaction was no better within the coalition of Christians and Muslims that was the Lebanese Army. They saw the Westerners as uninvited aggressors violating national sovereignty. Only Lebanese President Chamoun was pleased.

In a nationally televised speech, U.S. President Dwight Eisenhower pitched the idea in Cold War terms. He explained that Chamoun had requested U.S. assistance to stop threats from the Soviets and Egyptians, that U.S. intervention was necessary to prevent another war.

That ’58 deployment would be the beginning of a seemingly endless involvement of U.S. armed forces in the Middle East.

A Help or a Hindrance?

In August 1982, when Marines again landed across those same beaches, they joined elite troops from France and Italy as part of the Multinational Force in Lebanon (MNF). This time, the latest generation of State Department strategists did not frame the deployment in Eisenhower’s terms. Instead, the Reagan administration insisted the intervention was the best way to enforce a cease-fire agreement negotiated between Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO). As it had been in 1958, U.S. involvement in the early 1980s was at best arguably effective.

Most certainly, it led to catastrophe.

Initially, all was well. Yasser Arafat’s PLO withdrew from Beirut. Palestinians remaining behind were safe. But old passions from Lebanon’s long history were stirred. The cauldron simmered. It boiled over only a month later. President-elect Bashir Gemayel, also leader of the Christian-militia Phalangist Lebanese Army (PLA), was assassinated. Immediately—and, considering history, totally predictably—the PLA descended on the Sabra and Shatila Palestinian refugee camps. They slaughtered every man, woman, and child. Meanwhile, Gemayel’s younger brother, Amin Gemayel, was selected as the next president of Lebanon.

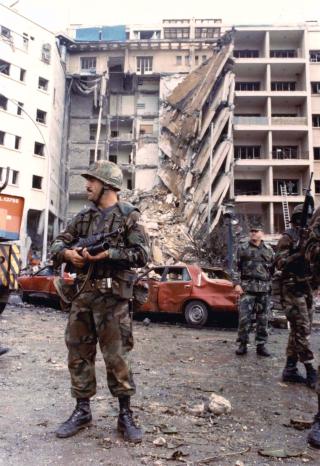

During the next five months the MNF kept their heads down and managed to keep a low profile. By February 1983, when something like stability seemed to return, the British joined the multinational peacekeeping force, such as it was. History repeated. What passed for calm in Beirut again vanished in a flash. On 18 April 1983, a car bomb destroyed the U.S. Embassy, killing dozens of Americans and Lebanese civilians.

The think-tank geopolitical thinkers didn’t anticipate anything like this. It took only a month for them to shift gears with another peace agreement. This time it shifted to withdrawal of remaining Israeli troops, if Syria did the same. But Syria refused to leave even as the Israelis departed. The new normal in Beirut became near-constant violence against foreign “peacekeepers.” Again, Westerners were seen as taking sides in yet another bloody Lebanese civil war. It seemed as though each new Western plan for intervention in the ancient land was just a fresh mistake.

In the midst of all this, the U.S. Marines carried on. They adapted and overcame. Nobody thought they would do otherwise.

‘Walking Targets’

To an observer arriving in September 1983, the scene from three miles offshore was as stunning as it was deceptive. All appeared well. Beneath the cloudless, azure sky of autumn, easterly winds pushed the emerald-tinged water ashore. Shallow waves washed languidly against vertical cliffs and even more gently across those long, sandy beaches stretching south toward Israel.

Seen from ships slowly steaming in circle-eight patterns, the city’s skyline did not show the effect of months of shelling. The variegated greens of palms and cedars rose steadily to foothills of the 10,000-foot Lebanon Mountains, which nearly span the country’s entire length. They were beginning to be capped with snow. In the slanting rays of an autumnal afternoon, the overall effect was postcard serenity.

It was as breathtaking as it was illusory. The reality was as complex as Lebanon’s geography. Unseen, unknown, unknowable dangers loomed heavy over the men of the 24th Marine Amphibious Unit (MAU) ashore.

The MNF territorial assignments were well defined. Elite forces from France, England, and Italy took positions in densely populated neighborhoods in the old city. That real estate lay along the north-south Green Line dividing Christian and Muslim neighborhoods. The much larger contingent of U.S. Marines was assigned the airport and beaches south of the city. The only exception was a detachment split away to the Lebanese University about a mile northeast of the airport.

The Marines’ geographic assignment made daily contact with the local population challenging at best. Training for the Lebanese Armed Forces (LAF) did continue—even including small attempts at “community relations” by inviting religious and civic organizations to tour the Marine airport position.

Like the terrain of all airports, there are acres of flat land with no obstructions. However, there were some permanent structures on the approximately 1 by 2–mile site, principally the Beirut International Airport terminal at the center of it. Farther north was a fire station, Lebanese Federal Aviation (FAA) buildings, an air-conditioning and power plant, and scattered warehouses and shops. Hangars and smaller service buildings were on the western, cargo side closer to the beach. They offered some cover.

Standing on this low ground, gazing up into neighborhoods to the east and north and plains to the south, it was immediately apparent the Marines were in a bad spot. From every direction, especially the eastern elevations, they were sitting ducks. The western perimeter was not much better. Literally a stone’s throw from Marine positions, it would be possible for a vehicle to speed by, to shoot or throw a grenade. The bottom line was apparent, and everyone knew it. From rifleman to Marine Commandant and to the more than 30 flag and general officers who visited regularly throughout the deployment, the position was a tactical nightmare, indefensible.

Still, daily routines were followed.

The almost 2,000 MAU Marines had deployed from Camp Lejeune, North Carolina. At any one time about 1,200 were ashore. They were resupplied daily by CH-46 and larger CH-53 helicopters. Every seven to ten days Marines rotated to ships for rest and relaxation. There the “walking targets,” as many referred to themselves, showered off the fine soil that, when dry, penetrated everything and, when wet, became a pasty gumbo clinging like cement. They slept on real bunks with real, clean sheets and ate well. Sailors treated them well.

But even rotations had their dangers. Chopper pilots adapted to small-arms fire and the occasional rocket by approaching fast and low. Ground time was brief.

There were some small amenities ashore.

that October. U.S. Marine Corps

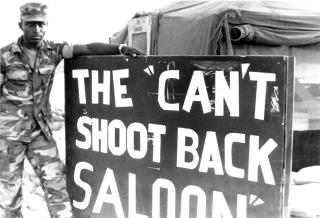

“LZ Red” was the only landing zone on a tarmac taxiway where takeoffs and landings didn’t stir up storms of the red dirt. Inside high sandbag walls, off-duty Marines could enjoy a menu that included cold beer, hard liquor, grilled chicken, and burgers. Anything was better than the Meals Ready to Eat diet of the line Marine. Nothing cost more than a half dollar.

Visiting news media and dignitaries enjoyed slightly better, if not marginally safer, hospitality. Within the solid walls of the FAA fire station, but still within striking range of the airport highway, the Joint Public Affairs Bureau (JPAB) staff set up an “officer’s club” for any number of the 300 news media in Beirut, many who visited daily. The headquarters for MAU Commander Colonel Tim Geraghty was upstairs. His staff and those of the JPAB lived below, in tents or in an adjacent FAA building. The “club” was also a distinguished-visitor lounge for high-ranking officers and their more anxious staffs waiting for rides out to the ships. From there, they would take a 90-minute helicopter flight to Larnaca, Cyprus. There they could board fixed-wing aircraft for another long flight to the naval air station in Sigonella, Sicily, or beyond.

The MAU’s communications trailer was only a few yards distant. It was a vital link to U.S. Navy Commodore Morgan France on board his flagship USS Iwo Jima (LPH-2) and to higher commands in Italy, Germany, England, and Washington, D.C.

Only a few yards south of the fire station, the Armed Forces Radio and Television Service (AFRTS) set up operations in a grove of cedars. The four-story poured-concrete FAA building became the Battalion Landing Team (BLT) headquarters, where gradually as many as 300 Marines could avoid random sniper and mortar rounds.

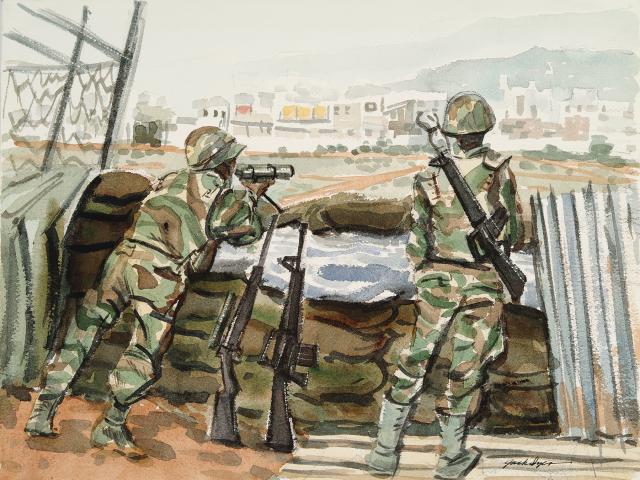

Some 200 yards north of the fire station, the Marines established their Marine Support and Supply Group (MSSG) operation to coordinate logistical, medical, and other support services ashore. Within feet of the airport highway and with clear view of its traffic, the location also had a tactical role. From sandbagged bunkers machine gunners kept vigil on passing traffic. More than once, Marines poured .30- or .50-caliber rounds into the motor blocks of confused taxi drivers or others—confused, or maybe with more aggressive intent.

Politicized Rules of Engagement

With only a few tactical exceptions, this “Rock Base”—MSSG, BLT, AFRTS, comms trailer, and fire station—was the center of Marine activity in Beirut.

Each day brought more danger. In response, movement outside the airport soon became rare. A fighting force hunkered down, hoping that the next rules of engagement (ROE) each Marine carried on a little white card would be amended from “minimum degree” self-defense that “respected civilian property” to “proportional response” more appropriate for combat-trained Marines under fire. At least the ROE authorized carrying a loaded weapon. It wasn’t all folly. Some changes did come over time, but it seemed to lack real-time operational relevance on a mathematical scale of how far away the issuing authority was from the on-scene commander.

Most, if not all at the airport, believed that ROE timing and degree did not honor the judgment of on-scene commanders but rather the murky, political considerations of a mysterious collection of intelligence operatives whose purpose and authority in Beirut weren’t clear, even to the Joint Chiefs of Staff. It ensured that any coherent mission definition had all but disappeared by September 1983. There was growing awareness that the Marines had no appropriate role in Beirut. This single reality, unspoken, was the first real indication of the tragedy that ultimately followed. Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger was frustrated with it all. He asked the key question, one that only a Cabinet Secretary could ask: “How do we know when we’ve won?” He never got an answer.

In typical Marine fashion, maybe the best answer came in an unofficial bootleg music video. The dark humor showed a young Marine slowly filling sandbags, stacking them around his own little hole in the ground. To the tune of Otis Redding’s “Sittin’ on the Dock of the Bay,” he sang an original lyric: “Sitting on my butt in the sand, wastin’ time, wastin’ time.” It was a big hit.

The Marines held on.

Their overarching orders were consistent: The Marines were at the airport, and there they would remain, at all costs. They would not conduct reconnaissance or remove imminent threats of attack. They were targets, pure and simple. As they did on many afternoons, they could watch snipers sighting-in firing lanes from adjacent neighborhoods. They could observe trucks delivering mortar tubes to the high ground east of the airport. Toward twilight, they most certainly noted arrival of armed men in pickups loaded with rocket-propelled grenade (RPG) launchers and ammunition.

Friday nights were prime time for all of this. After a break for prayers at local mosques, the fireworks would begin, often between rival factions and especially when the Christian army was pinned down. But, as though on cue, the red RPG tracer tails changed from uphill to downhill trajectory. Soon, all rounds drifted down the hillsides to land in the airport. Then, and only then, and only with specific targets that had not been smart enough to move, could the Marines open fire on them. The “Blue Flames” as the locals called Marine artillery, had only limited effect. Ironically, the best results came not from outgoing high-explosive artillery rounds, but from what appeared to be modified Fourth of July fireworks. Pop-up flares shot from mortars arched high overhead, ignited, and slowly fell to earth with the brilliance of near-daylight. The message was clear: “We see you. Knock it off.” Almost always, incoming ceased.

Incoming at the airport increased in proportion to the steady degradation of President Amin Gemayel’s armed forces. Not only was he losing power in a place where might-makes-right has ruled for centuries, but this young president who had succeeded his assassinated brother Bashir also was losing political credibility. Unable to impose his will, he would not have a role in any new government after the civil war. He needed help. He got it from his allies in Washington, D.C. The USS New Jersey (BB-62) was on the way.

Gunboat Diplomacy Redux

The World War II–era battleship had been recommissioned in January 1982 with great fanfare. Indeed, President Ronald Reagan was so intent on attaching his persona to the symbol of America’s naval supremacy that just two weeks prior to the ceremony he changed the date to ensure he could preside.

In April 1983, the behemoth steamed to Hawaii and the Philippines on a shakedown cruise. Next, President Reagan added to her mission, ordering the battleship to steam across the Pacific to the Gulf of Fonseca. The giant ship remained off the coast of El Salvador until mid-September, showing the flag and her massive 16-inch guns. The message to rebels in the tiny nation was obvious, classic gunboat diplomacy: They had better heed the U.S.-backed government.

The Commander-in-Chief wasn’t through. His plans for the New Jersey’s already overworked crew could not have been worse. Responding to President Gemayel’s dilemma, “The Gipper” reasoned that what had seemed to help the new government in El Salvador would have the same effect on another shaky one in Lebanon. Hours after Reagan learned of army losses in Lebanon, the Commander-in-Chief, Pacific Fleet, at Pearl Harbor sent the bad news to the New Jersey’s commanding officer, Captain Dick Milligan. Already at sea for six months, the crew would not return as promised to home port in California. They were to transit the Panama Canal, then steam at flank speed across the Atlantic and Mediterranean.

On 24 September 1983, as the first rays of day rose above the Lebanon Mountains, the New Jersey arrived off Beirut Point. What had begun as a four-month cruise was evolving into a 13-month deployment, one unprecedented in modern naval history.

On Tuesday afternoon, 27 September 1988, Colonel Tim Geraghty and Commodore Morgan France gathered key staff in the MAU headquarters. Barely audible beyond the sandbags blocking gaping holes that once held windows, small-arms fire cracked far outside the airport perimeter.

Unintended Consequences = Dangers Rising

In turn, both commanders spoke of the constantly changing, life-and-death operational responsibilities now long routine for them. The bottom line was clear: The situation was deteriorating. Logistics was becoming much more dangerous. Driving through Beirut was almost impossible because of near-constant sniping and detonations of roadside bombs. Face-to-face liaison with other MNF personnel was rare. Resupply to U.S. Ambassador Robert Dillon was now by boat.

Although Tactical Airborne Reconnaissance Pod System (TARPS) missions vastly refined intelligence, the F-14s from the recently arrived USS Dwight D. Eisenhower (CVN-69) also had an unintended consequence. Their presence, like that of the New Jersey, ratcheted tensions even tighter. Factions in the foothills, whose artillery movements were now graphically documented, responded by trying to shoot down the camera-equipped Tomcats that were exposing them. As was now permitted by the ROE, the Americans answered with artillery. So common was this that it inspired more dark humor. TARPS missions were referred to in TV game-show terms: “Trolling for Targets” was the grim description.

On everyone’s minds, and unspoken at first, were questions about what the New Jersey’s arrival meant. The battleship took care to remain visible offshore. Until now, the huge 16-inch guns had lain silent. To the men gathered in MAU headquarters as well as to all the warring factions, the perception of U.S. neutrality had long ago vanished. Anxiety about potential threats to that neutrality were through the roof. All asked the same question: What’s next?

Under the ROE of proportional response, naval gunfire support (NGF) had been used on discrete targets, in the same way that U.S. mortar and artillery had been for weeks prior. The first NGF had come on 16 September when the frigate USS Bowen (FF-1079) and destroyer John Rogers (DD-983) poured more than 70 rounds on six targets after the Lebanese Ministry of Defense and the U.S. Ambassador’s residence were shelled.

The New Jersey’s arrival potentially brought NGF consideration to a new level. The inferred message from the White House was unspoken, and obvious: What worked weeks earlier in El Salvador had better work in Beirut. To men wargaming thousands of miles away, all was academic. But for the commanders in Beirut, there was serious, sober concern for the lives of men in harm’s way. What would delivery of 2,400-pound high-explosive rounds, landing as far as 20 miles inland and capable of vaporizing entire city blocks, have on the now-almost laughable idea of neutrality?

It took no imagination to picture the results. This time, actions might even lead one to assume that the foreign, Western interloper was preparing for all-out war, past the mountains, descending into eastern Lebanon’s Beqaa Valley, and marching all the way northeast to Damascus, Syria.

Throughout the meeting, Geraghty and Morgan knew their words were being monitored far away. The listeners had their own agendas, well aware they had a popular, media-savvy Commander-in-Chief to please. President Reagan’s approval polling was high. Listening in on the red phone on Geraghty’s desk was an admiral on board the Eisenhower; others listened at Sixth Fleet Headquarters in Gaita, Italy, more in U.S. European commands in Stuttgart, Germany, London, England, and at Commander of the Atlantic Fleet’s headquarters in Norfolk, Virginia. There were ears also in the White House Operations Center, quite possibly including Vice President and former Central Intelligence Agency Director George H. W. Bush. He knew “The Gipper” well.

When the call ended, all in the little room at the airport sat motionless, each with his own thoughts. Eyes settled on the red speaker phone or on each other. There were no clairvoyants in the room, but it is probable all knew what the other was thinking: The battleship’s arrival, why it was sent, the jets screaming low overhead, had changed everything.

A clock had started. It was only a matter of time.

‘How Do We Know When We’ve Won?’

The Marines carried on.

In October 1983, intelligence indicated at least two large trucks were being loaded with high explosives. Their location and potential targets were unknown. Specifics came a few days later.

At 0622 on 23 October 1983, a yellow 19-ton Mercedes stake truck crashed through the lobby of the Battalion Landing Team headquarters and detonated. The blast killed 220 Marines, 18 sailors, and three soldiers.

It was the Marine’s largest single-day loss since Iwo Jima during World War II. It was the largest non-nuclear blast ever recorded.

Almost at the same exact time, a second truck exploded at the nine-story French MNF headquarters building. Fifty-five paratroopers from the 1st Parachute Chasseur Regiment and three from the 9th Parachute Chasseur Regiment were killed. Not since the Algerian Revolution of 1962 had the French suffered such a single-day loss.

On 14 December 1983, the New Jersey fired 11 16-inch rounds into hostile positions in Beirut. The high-explosive shells were the first such fired since the battleship had ended her 1969 Vietnam gunline tour. On 8 February 1984, the battleship fired nearly 300 16-inch rounds into Druze and Shi’ite positions in the foothills overlooking the city. Thirty cleared the Lebanon Mountains and rained death on a Syrian command post in the Beqaa Valley. It was the heaviest shore bombardment since the Korean War.

On 26 February 1984, the Marines and the U.S. Sixth Fleet sailed over the horizon. Secretary Caspar Weinberger’s question—“How do we know when we’ve won?”—still remains unanswered.

Almost 40 years passed before some in Congress tried to memorialize America’s brief moment in Beirut’s ancient history. On 23 October 2019, U.S. Senator Tom Cotton of Arkansas introduced Senate Resolution 374 to establish a national day of remembrance to commemorate the Beirut Marines. It is still pending. On 25 May 2021, U.S. Representative Greg Pence of Indiana introduced House Resolution 442, with the same intent. It never made it out of committee.

In time, and with benign neglect, memory fades, perhaps faster for unpleasant truths. Perhaps William Faulkner knew this when he observed, “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”

His words may caution that history can and will be forgotten—but always at great peril.