For many U.S. Marine commanders who rose to prominence in the World War II–Korean War era, an often understudied period of their careers was their service in the interwar U.S. interventions in Central America and the Caribbean. One such officer was Lieutenant General Edward A. Craig, who would earn the Navy Cross for leading his regiment in the recapture of Guam and command the 1st Provisional Marine Brigade—the illustrious “Fire Brigade”—in its defense of the Pusan Perimeter.

Unlike most Marines who served in Nicaragua during the “Banana Wars,” Craig volunteered for duty in the Guardia Nacional de Nicaragua (Nicaraguan National Guard). He would learn leadership lessons while commanding native troops against a determined foe—rebel leader Augusto Sandino—and his fighters, which the Marines referred to as “bandits.”

In June 1926, after service in Haiti and the Dominican Republic and sea duty on board the USS Huron (CA-9), then-Captain Craig was assigned as aide-de-camp to Major General John A. Lejeune, Commandant of the Marine Corps. While accompanying Lejeune on an inspection tour of Nicaragua in 1928, he “became interested in the Guardia Nacional de Nicaragua,” Craig explained. “Soon after our return to the United States, the general’s tour as Commandant expired, and I asked him if I could be detailed to duty with the Guardia, [because] I believed that I could be of some help to the organization.” Lejeune agreed, and in May 1929, Craig received orders to report to the Jefe (Chief) Director of the Guardia, Brigadier General Douglas C. McDougal, a colonel in the Marine Corps.

On 19 May 1926, Congress had authorized President Calvin Coolidge to “detail officers and enlisted men of the United States Army, Navy, and Marine Corps to assist the governments of the Republics of North America, Central America, South America and the Republics of Cuba, Haiti, and Santo Domingo, in military and naval matters.” About seven months later, amid a civil war in Nicaragua between Conservative and Liberal forces, Marines landed in the country to protect U.S. lives and property but were soon drawn into the fighting. The United States mediated a peace settlement ending the conflict in May 1927.

Two of the agreement’s provisions were the establishment of a nonpartisan constabulary under the command of a U.S. officer and the continued presence of the Marines to enforce the settlement’s other provisions. It was hoped that the constabulary—the Guardia Nacional—would be a stabilizing influence on turbulent Nicaraguan politics and ensure free and fair elections.

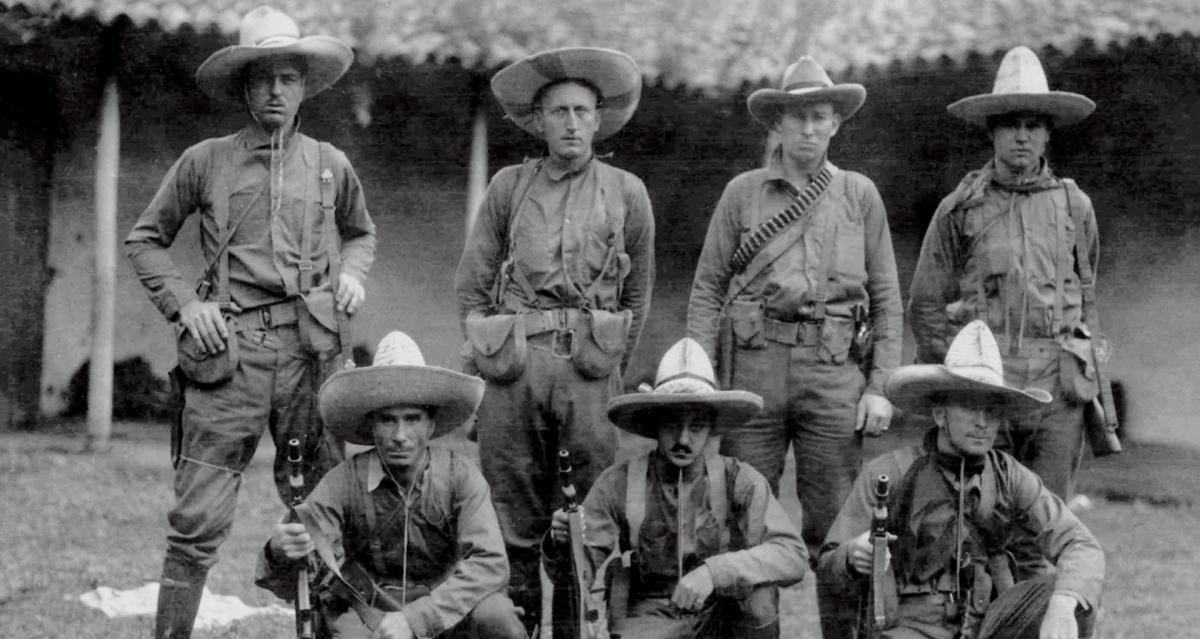

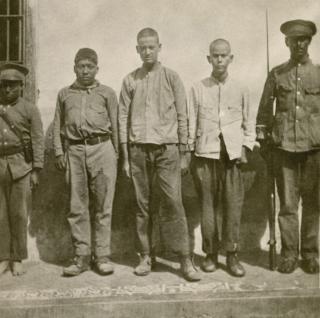

Commanded by an active-duty U.S. Marine colonel, the Jefe Director, who would report directly to the President of Nicaragua, the Guardia was to consist of 93 officers and 1,136 enlisted men, according to a December 1927 agreement. The manpower level would vary depending on funding, and by February 1931, it was 204 officers and 2,150 enlisted men. Volunteer Marine officers and enlisted men were selected to lead the Guardia. Enlisted Marines were given initial appointments as cadets and, if qualified, commissioned as second lieutenants in the Nicaraguan service.

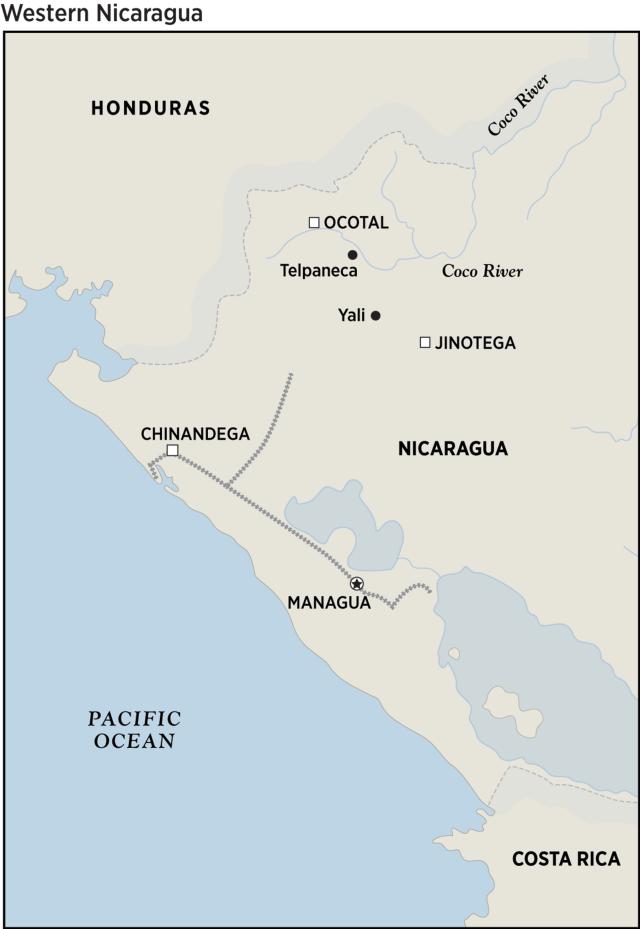

While the Guardia initially functioned as a police force, by the summer of 1927, some of its units were in the field, supporting Marine operations against rebels, most notably Sandinistas. Sandino had refused to abide by the peace settlement’s provisions, which included laying down his arms. His men primarily operated in the country’s northern and central hinterlands. According to historian Bernard Nalty, Sandino was a “zealot in the cause of Nicaraguan Liberalism . . . who claimed that the Marines were ‘a bunch of dope fiends . . . come to murder us in our own land.’”

When Captain Craig arrived in Nicaragua, he was assigned as the executive officer of the Guardia’s 1st Mobile Battalion, under Major Roy “Plug” Lowell, headquartered in central Nicaragua at Jinotega, the capital of the Department of Jinotega. “Jinotega was a depressing place,” Craig explained. “High in the mountains it was subject to frequent rains . . . the dirt streets were poorly drained and . . . either muddy or very dusty. The natives were not friendly. Many of them had friends or relatives operating with Sandino’s forces. They resented the presence of the . . . Guardia Nacional, and especially their white officers.” Craig found the town increased his “feeling of depression and isolation.”

As the captain explained: “Commanding native troops was a constant strain. Being the only white man among 50 or a hundred of these native troops while on patrol, with only a poor command of the Spanish language, could be nerve-wracking. In some instances, the Guardias had mutinied and shot their own officers. Desertions were frequent.” However, Craig did not have any trouble and found that the Nicaraguans were good soldiers and loyal if they were treated fairly.

When Craig arrived in-country, “the Guardia was in the process of taking over many of the outlying outposts that the Marines had previously manned, and from there they were operating against the bandits [in a combat role].” Although he was the mobile battalion’s executive officer, Craig spent much of his time in the field, “either on patrol or on patrol inspections of the many outposts. These outposts were spread over a wide area that was mountainous and sparsely settled. Only narrow muddy trails connected the various small towns where the Guardias were stationed.”

“Life on patrol was difficult,” Craig maintained. “Our patrol equipment was of the simplest nature. We had to eliminate every extra ounce of weight in order to conserve our strength on long hikes. I usually carried only a pistol belt with suspenders. On this I hung my pistol, first aid packet, canteen, and compass, with four magazines of ammunition. My poncho or light blanket was usually folded over the back of the belt or hung on my suspenders. I carried a Marine Corps dispatch case, which I used for maps, rations, and other odds and ends, including my toothbrush. My shoes were either Marine Corps issue or high laced leather boots, [and I wore] khaki breeches and flannel shirt. The Guardias were armed mostly with the Krag rifle. Some were equipped with the Browning automatic rifle [BAR] or Thompson submachine gun. Others had the Springfield rifle with rifle grenades and one or two hand grenades.”

He recalled: “On one occasion, in a wild section of Nicaragua, I had a small, 18-man patrol that had exchanged fire with a bandit group. For six days we had hiked through the jungles and over the mountains endeavoring to gain contact. It had been down one mountain and up another, usually off the trails or across swollen rivers. Our clothes were wet and rotten, and my shoes about to fall apart. Each night we would camp on the wet ground . . . no fires were lit. . . . The nights were ice cold . . . and our only covering was a light blanket.

“On large patrols we sometimes took pack mules to carry coffee, beans, and rice, but more often we carried our meager rations on our person. We foraged for food along the way, if time permitted, but many times we would be in an area that was absolutely desolate.” One time on a long patrol, his men were running low on food, so they shot several monkeys. Craig and the Guardias found a burned house and the remains of an old fire with a large iron pot of beans over them. On breaking through a top crust of hardened beans, they discovered the remaining beans to be crawling with worms. “Nevertheless, my men turned to on the beans and monkey meat. I could not go [for] the monkey meat but took a small helping of the beans, from which I separated the worms as best I could.”

After several months with the mobile battalion, Craig received orders to take a company of Guardias and relieve a unit of the 5th Marines garrisoning the mountain village of Yali, a small settlement of about 250 people “situated in the high mountains.” A narrow trail that ran over rugged terrain connected it to small adjoining hamlets. Craig’s mission was to suppress banditry, police the area, and build roads.

“My company was composed of drafts from the other companies of the battalion,” he explained. “On the morning of our departure, men released from the brig filled up the vacancies in the company. It was a mongrel outfit.” With some degree of trepidation, Craig and his second in command, Second Lieutenant Frank L. Kurchov (a corporal in the Marine Corps), marched their “crack” troops into the jungle. Just a few hours after starting out, one of the former “brig-rats” tried to shoot Kurchov. The lieutenant-cum-corporal wrestled the rifle away and brained the man with his own weapon. The bashing quickly ended the abortive mutiny.

Soon after reaching the post, Craig received word that a Guardia detachment had mutinied and kidnapped their officers. It was expected that others might mutiny and go over to the bandits. “At the time, Kurchov was out on patrol, and not knowing my men too well, I was pretty nervous when I turned in that night.” Craig slept with a BAR under his cot.

The next day, one of the sergeants asked if the detachment could serenade him after work. “It was not unusual to serenade people in Nicaragua, but I thought it strange under the circumstances. As darkness set in, I became more nervous when they did not appear. About eight o’clock, there was a knock on my door, and when I opened it, every man who was not on duty was standing there.”

The men requested to come in, and Craig did not have a choice. “I thought to myself, ‘Well this it, they have me cold!’” They squeezed in and arranged themselves around the small room. A small kerosene lantern provided a weak light as the hard-looking group crowded around the captain. “To say I was afraid would be putting it mildly.” Finally, a man started strumming his guitar—and the whole group broke into song. “The group loosened up when I passed out cigarettes and coffee. They cracked jokes and smiled. I finally understood; they were showing me their loyalty. I never had trouble with the men after that and always felt secure when with them.”

Life in the Guardia was one crisis after another. Craig was in his office one morning when a shot rang out and a bullet thudded into the wall beside his head. “Seems a Guardia who had just enlisted let his rifle go off while on guard in the tower. He deserted the next morning, and I never did find out if the shot was accidental or intentional.”

Another crisis involved a murdered civilian. “In the Department of Chinandega [in northwestern Nicaragua], we had an average of two or three machete-fight killings between civilians each month. The winner of the fight became a hunted man, and many joined the bandits or went over the border to Honduras.” After one of the fights, the “winner” was arrested and incarcerated in the local hoosegow. Unfortunately for the miscreant, the jailer was a relative of the victim.

Craig was notified that a riot had developed after the prisoner was savagely murdered in his cell. “I found a milling crowd of some 2,000 Nicaraguans in front of the cuartel [jail]. The body of the murdered man lay on the street, guarded by four Guardias. I could see a dangerous situation was in the making and ordered an interpreter [to] tell the mob that I would investigate . . . and in the meantime stay calm.” While the interpreter talked with the crowd, Craig telephoned for reinforcements. Just as the situation was turning critical, ten Guardias carrying a machine gun roared up—in the best tradition of the cavalry. “When they had set it up, the mob began to disperse, and in 20 minutes the last one disappeared.”

The Guardia was tough, and according to Craig, its soldiers had to be to deal with Sandinista bandits and other criminal elements. “I remember on one occasion, I gave orders to a Guardia to arrest a murderer. Later on in the day, I heard a loud thump outside my door. A Guardia came in and handed me a large pearl-handled .44 revolver and told me the prisoner was outside. I said, ‘Bring him in.’” The Guardia went outside and reentered, dragging a body by the legs. “It seems the man was armed, and the Guardia, not wanting to take any chances, fired first. The thump I heard was the body being dumped from the Guardia’s horse.”

The captain found that he always had to be on the alert for brutality. “In a country where . . . water cures and hot pepper enemas were routine questioning techniques, one had to be on the watch to prevent excesses on the part of the Guardias.” He had a burly Nicaraguan first sergeant who always seemed to be able to extract information from prisoners. “I was passing a small room off the sally port and found his method was to have a Guardia hold the prisoner, while he grabbed his testicles and twisted. Being a powerful man, it seems only a few twists were necessary.”

In 1929, the Nicaraguan government commenced a road-building program to improve the economy and gainfully employ would-be bandits. Craig laid out the route for a two-lane road and hired 300 Nicaraguans at 50 cents a day. “Many of the men I employed were part-time bandits, and when most of them did not show up for work, I could always count on increased bandit activity while they were away.”

The captain observed that sometimes the workers would be sullen and at other times smiling and contented. In an effort to improve morale, he decided to throw a big party. Craig was “rather nervous” about attending because of the threat of a bandit attack. “I asked my head man whether he thought the bandits would interfere. He laughed and put his arms around my shoulders and said: ‘Never worry, there are too many of them right here. You will have no trouble at all!’”

On one occasion, Craig sent out two of his best men dressed and armed as bandits. “They encountered two of my workers on a side trail and identified themselves as members of Sandino’s army. The undercover Guardias asked the workers to guide them in an attack on Craig’s post. “The two immediately gave the information and stated they would help in the attack, if given rifles, as they hated the government and the Guardia.” The two were arrested, and Craig was surprised that they were among his best workers. “Sometimes between my Guardias and my workers I had a hard time deciding who to trust.”

Normally, when Craig supervised the road gangs, he rode with four to five Guardia escorts. One day, however, he sent them on ahead—and almost immediately regretted the decision. “I was rounding a sharp curve. A deep valley dropped away on one side and a ridge looked down on me from across it. A bullet smacked against the stone cliff, missing me by inches, and I heard the report of a rifle.” Craig put spurs to his horse and bounded to cover before the hidden rifleman could fire another shot.

Shortly after taps one night, Craig’s post was attacked. “The bandits took up positions around the town and fired into our barracks. However, we had made plans for just such an emergency. Selected Guardias manned defense positions while the bulk of my outfit formed an attack force. We fanned out through the village, and the bandits fled to the bush.” At first light, Craig’s men searched the small town but found nothing except hundreds of expended cartridges.

On another occasion, while he was with the road gang, 12 bandits waved to him with their rifles. “They stood and watched us for some time but offered us no resistance and finally left. I had only two of my Guardias with me at the time and did not feel that we should start a battle.”

After two and a half years in Nicaragua, Craig received orders to report to the embryonic 1st Marine Division at San Diego. At the time, the Corps’ presence in Nicaragua was being reduced prior to the 2 January 1933 departure from the country of the last Marines, including those serving in the Guardia Nacional.

Craig’s orders directed him to travel via a Navy oil tanker. After all the hardships he had suffered, Craig requested to proceed at his own expense; he wanted to come home in style. “Accordingly, I boarded the SS Columbia of the Pacific Mail Steamship Company on September 3, 1931.” After several stops along the coast, the ship docked at Mazatlan, Mexico, where the passengers went ashore for a celebratory party. “Returning to the ship, we continued to party in the bar.”

After getting under way, the ship encountered rough weather and high winds. Craig went below to his stateroom. “What a relief to have a clean cabin, hot shower, and all the comforts of home. I lay down and relaxed on my bunk and thought how smart I had been to travel in this luxury.”

Craig dropped off to sleep, but he woke up to find himself on the deck. He quickly realized the ship was in trouble and grabbed some personal articles and headed topside. “I could clearly see that we were aground. . . . The captain gave the order to abandon ship.”

The lifeboats were swung out and all women and children were loaded successfully. “When my turn came to leave, I had to climb down a Jacob’s ladder. As I was about halfway down, crude oil spurted from a split seam in the side of the boat and covered me and everyone else in the lifeboat.” Craig manned an oar, along with some of the crew, and started to pull away from the ship.

“The captain [Theodore K. Oaks], known as ‘Whispering Oaks’ because of his name and low voice, yelled down, ‘Don’t light any matches or it will burn up.’ The engine room crew, who were not too fond of him, yelled back: ‘shut [up] you old son of a bitch. We hope you go down with the ship!’”

Sources:

Lt Gen Edward R. Craig, USMC (Ret.), oral history transcript, 1968, History Division, U.S. Marine Corps.

Lt Gen Edward R. Craig, USMC (Ret.), “Note on Incidents of Service, 1917–1951,” unpublished manuscript in the author’s possession.

Lt Gen Edward R. Craig, USMC (Ret.), interview with the author.

Brent Leigh Gravatt, “The Marines and the Guardia Nacional de Nicaragua 1927–1932,” master’s thesis, Duke University, 1973.

Bernard C. Nalty, The United States Marines in Nicaragua (Washington, DC: Historical Branch, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps, 1958, 1969 reprint).