Late in the summer of 1740, an eight-ship Royal Navy squadron set sail from Spithead for a voyage around the world. Four years later, when the tattered remnant of Commodore George Anson’s original complement returned at last, just one ship and only 188 of the original 1,854 men had survived. They had endured scurvy, storms, starvation, bad charts, and bad luck. To the bitter end—when they had to sneak past a French squadron in the English Channel fog to limp back into Spithead—Anson’s voyage had been a seafaring torture test.

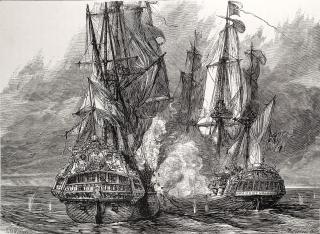

But it was not without its successes. As intended, the expedition raised some hell with the Spanish in the Pacific. Anson’s travels inspired the explosion of British Pacific exploration in the ensuing decades. And as the crowning jewel of the undertaking, Anson and co. had captured the treasure-laden Manila-to-Acapulco galleon—a heady windfall that brought them great fame and a hero’s welcome at home.

And, as retired U.S. Navy Captain Thomas R. Beall illustrates in our cover story this issue, Anson’s voyage brought back something of vastly more far-reaching value than Spanish treasure: a whole host of valuable lessons learned that would assist Britain’s pending emergence later in the 18th century as the world’s dominant global naval power. From Anson’s hard-earned experiences, there are takeaways as well for the U.S. fleet—historical insights worth heeding today.

It was 55 years ago this July that the U.S. Marine Corps likewise was absorbing lessons from hard-earned experience: As the final Marines evacuated Khe Sanh after their legendary stand there during the Vietnam War, there was much to digest about a damnable new tactic they had encountered that took ruthless advantage of one of the Corps’ most noble traits—to leave no Marine behind, dead or alive. Michael Archer, who was there at Khe Sanh, returns to our pages to take a sobering look at the “Deadly Dilemma.”

This July also marks another signal anniversary—70 years ago, the longest naval blockade in modern history, the Siege of Wonsan, concluded in July 1953 after a staggering 861 days. U.S. and allied forces relentlessly battered the strategically vital port city and kept it locked out of the action for the duration of the Korean War. Edward J. Marolda shines a light on this historic operation, a large-scale yet often-overlooked aspect of the Navy’s crucial role in the Korean conflict.

Last issue, we presented the unique story of how the USS Wasp (CV-7) aided the British in the defense of Malta in summer 1942. This issue, we bring you a “prequel” of sorts, as retired U.S. Navy Captain Michael Lilly offers up a wild anecdote about the Wasp’s collision with the USS Stack (DD-406) on Saint Patrick’s Day 1942. Also on the World War II front, Thomas Wildenberg regales us with an account of the remarkable feat of the USS Sealion (SS-315)—the only Allied submarine to sink a battleship in World War II.

J. M. Caiella, meanwhile, tells the tale of an entirely different sort of battleship—one that could exist only in a kid’s imagination. In this amusing piece of naval Americana from 1898, we see how children around the country raised funds to build a battleship to replace the USS Maine; the proposed vessel, The American Boy, was fanciful, to say the least, but its groundswell of support among the nation’s youth is an inspiring thing to look back on and ponder.

Lastly, in honor of the U.S. Naval Institute’s 150th anniversary year, we present the second in our trilogy of articles chronicling the early exploits of the Institute’s founding president, John L. Worden. In this installment by Robert L. Worden—a descendant of Worden’s, no less—we sail along with young Midshipman Worden as he goes pirate-hunting with that colorful Old Navy legend, Captain “Mad Jack” Percival. Auspicious beginnings for John Worden, indeed!

Eric Mills

Editor-in-Chief