It was more frightening than when I was attacked by kamikazes!” said P. A. “Tony” Lilly about his experience on Saint Patrick’s Day 1942.1

The night before, 24-year-old Ensign Lilly had the first watch (2000–2400) as officer of the deck (OOD) on board the 1,500-ton Benham-class destroyer USS Stack (DD-406). The Stack was part of Task Group 22.6, steaming south from Portland, Maine, to Norfolk, Virginia, with the USS Sterett (DD-407). Both were escorting the two-year-old 14,000-ton aircraft carrier USS Wasp (CV-7).

The Wasp was commanded by Captain John W. “Black Jack” Reeves Jr. His nickname was “not from any acumen at cards. Tough, demanding, and often abrasive, he was nevertheless experienced and capable.”2

The Stack and Sterett were protecting the Wasp from German U-boats. In January 1942, German Admiral Karl Dönitz had launched Operation Drumbeat, “a mass U-boat assault on merchant shipping along the East Coast and in the Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico.”3 During the first half of 1942, 12 U-boats sank 585 merchant ships. Five were reported to be operating near the Wasp.

The Stack was steaming 3,000 yards off the Wasp’s starboard bow and did not have radar. Accordingly, Lilly maintained position by estimating the size of the carrier in his binocular field. Late in his watch, however, a fog rolled in and gradually obscured the carrier. Lilly kept the Wasp in sight by closing the range to 2,000 yards.

With a new moon, the night was dark and quiet, without wind or chop—“a vast and oily sea,” as Lilly described it. The ships were operating under emissions-control conditions to avoid detection by U-boats. Communications between the carrier and the destroyers were limited to the line-of-sight talk-between-ships VHF radio. Lilly had no apprehensions, but he should have.

At midnight, Ensign Clarence Zurcher relieved Lilly for an uneventful midwatch. At about 0330, a ruddy Irishman, Ensign John J. McMullen, appeared on the bridge to relieve Zurcher for the morning watch (0400–0800).

Zurcher gave McMullen the ship’s course and speed (232°T, 23 knots), the positions of the Wasp and Sterett, and the night orders issued by the Stack’s commanding officer, Lieutenant Commander Isaiah “Cy” Olch.

As the fog thickened, the Wasp slipped in and out of view. At 0445, visibility was down to 1,000 yards. At 0510, with visibility reduced to 100 yards, McMullen informed Olch through the bridge voice tube that he had lost sight of the Wasp, causing Olch to come to the bridge and assume the conn. Olch radioed the Wasp, asking for the Stack’s range and bearing. The Wasp replied that the Stack was bearing 237°T at 1,200 yards, indicating that the destroyer had moved from the carrier’s starboard bow to her port bow. Olch altered course right to 236°T and reduced the Stack’s speed to 22½ knots “to pull out onto station slowly.”4

Ten minutes later, an update showed the Stack bearing 222°T from the Wasp at 2,200 yards. Thus, despite the Stack’s course change to starboard, she was now “decidedly to the left of the first bearing.” At 0540, the Stack was bearing even farther to the left of the Wasp—206°T at 2,000 yards. Olch ordered the Stack to come “right to course 245 degrees.”5 The Sterett also was reported off station.

Shortly after the helmsman steadied the Stack’s course on 245°, a dark silhouette appeared through the fog, slightly aft of her starboard beam. It had no form but was growing larger. At 0543, breaking out of the fog 150 yards away, the edge of the Wasp’s flight deck appeared and bore down on the Stack at a sharp angle. With the fog deafening sound like a muffler, the night was strangely silent. But that would soon end.

At 741 feet and ten times the weight of the Stack, the Wasp dwarfed the 341-foot destroyer. Both ships were in extremis. Olch ordered evasive maneuvers as the gap between the ships closed. “[T]he rudder of the Stack was put hard left, emergency full speed ahead on both engines, and collision quarters were sounded.”6 Collision was now inevitable.

Less than a minute after sighting the carrier and before the increase in the Stack’s speed and change in rudder angle could take effect, the Wasp plowed into the Stack just aft of her bridge. Sparks flew. Massive vibrations shook the Stack. Everything not secured became a projectile. Those standing were thrown to the deck, and the arms of those holding onto anything were wrenched severely.

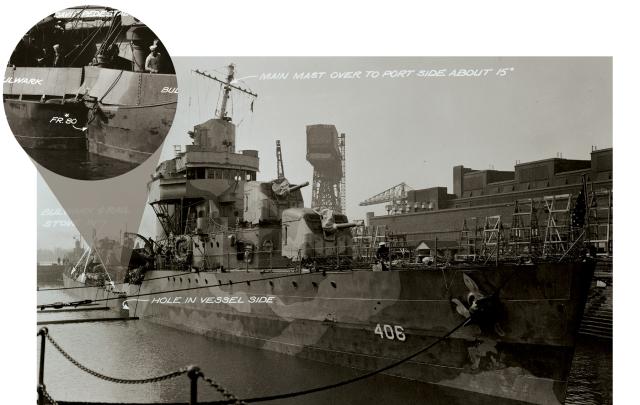

The Wasp crushed the Stack’s motor whaleboat and sliced into and flooded her forward fireroom “just shy of the keel.” A few inches more and the destroyer would have sunk with all hands.

Olch immediately ordered all engines to stop. The Stack slewed around and became impaled on the Wasp’s bow, which propelled the destroyer sideways through the ocean at 23 knots.

Meanwhile, Lilly was thrown from a deep sleep into the “scuppers” of his room as he heard the ship’s collision siren. His first thought was, “Mac was chasing a submarine.” In those days, Lilly recalled, “Submarines usually steamed on the surface at night and dove at daybreak, staying under all day.” The most likely time to encounter a submarine was during the 0400–0800 watch, when Lilly and McMullen planned to “wheel the ship into a collision course and then report to the captain.”

Lilly’s stateroom was heeled over at a 60-degree angle. With difficulty, exacerbated by the pitch of the room, he donned Arctic overshoes, foul-weather gear, and a life jacket and made his way to the Stack’s main deck with other members of the crew who were streaming out of hatches.

Through the fog, Lilly discovered the most frightening sight of what would be a 30-year Navy career. The bow of the Wasp was buried in the starboard side of his ship. “The overhang of the Wasp’s flight deck knocked over the foremast and bent over the top of the smokestack.”7

Lilly scrambled to his abandon-ship station on the forecastle, starboard side, just forward of the Wasp, and gripped the Stack’s handrail. “I looked over the side into the roiling icy waters and shuddered at the thought of how long I could survive in the North Atlantic in winter.” Assuming water temperature between 32 and 41 degrees Fahrenheit, he would have lasted no more than 30 to 90 minutes.8

As swells passed under the two ships, the Wasp would rise faster. The Stack, which was heeled over at a steep angle, tried to right herself. But as the ships settled into a trough, the Wasp thundered down, punching the Stack over with a crash and sawing into her hull, closer and closer to the destroyer’s keel. Water flowed into all compartments from the port side and threatened to capsize the Stack.

“On each downward thrust,” recalled Lilly, “the Wasp smashed onto our stack.” The only noise, except for the ships grinding together, was “my shipmates swearing futilely at the Wasp.”

Above Lilly loomed “the overhang of the flight deck above the opening into its hangar deck. Smoke from our stack poured into the carrier’s hangar deck. Eventually, I heard the Wasp ring its bell rapidly, followed by the stroke of one bell, meaning they thought a fire had broken out in the forward part of the carrier.”

“During the wild minutes that followed, the Stack’s crew performed with the coolness and courage that had much to do with her becoming known as a ‘lucky’ ship.”9 Damage-control parties carrying flashlights tried to stop flooding in the forward fireroom, but the extreme heel prevented “complete plugging of the hole.” Watertender First Class Ollie Lee Uzzel “was the last man to leave the crushed forward fireroom; but when he did leave all hands were out safely and the fireroom secured.”10 Along with flooding, electrical fires broke out in the steering engine room number two fireroom, and the control engine room, but were soon extinguished.11 For his actions, Uzzel was awarded the Navy and Marine Corps Medal.

Torpedoman First Class Frank LeRoy Knight “worked his way down the crazily tilting decks against heavy seas beating directly on the ship to secure the depth charges and prevent their being detonated under the carrier.”12 Ready to launch against U-boats, the 24 depth charges were armed to explode when they reached a specific depth of water. Pummeled with heavy waves and “despite the pending danger of the depth charges being dislodged by further contact with the carrier, Knight . . . set all the depth charges on ‘safe,’” thereby saving both ships from further disaster. Knight was awarded the Navy Cross.13

Because “we were clear under the bow of the carrier,” Lilly continued, “her bridge could not see us. Eventually, the carrier’s fire control parties peered down over the edge of the hangar deck searching for the source of the fire. Instead, they found the strangest sight of their careers—the Stack hung on their bow.” A Stack sailor located a battery-powered blinker gun to communicate with the Wasp’s fire control parties.

At 0610 the Wasp “reduced speed through the water, slowed down, and backed clear.”14

The Stack righted, but was dead in the water and “almost awash back aft,” recalled Lilly. “We had only a few feet of freeboard amidships, and much less aft.” The Stack had lost all power, had no radio, no electricity, and no lights. Without power to run water pumps, the crew formed daisy chains to carry buckets of water from compartments to the main deck.

Amazingly, “many men were washed over the side,” but the “freak position of the ships caused them to be washed back aboard.”15 A “signature muster was taken of all hands at daylight, and all personnel were accounted for.” Fortunately, not a single person was “injured as a result of the collision.”16

Fearing U-boats, the Wasp and Sterett left the disabled Stack to fend for herself. Reeves sent a message to the fleet commander: “Have been in a collision believed to be Stack (DD-406). Have directed Stack to proceed Norfolk.” That sounded to Lilly like a typical Black Jack message.

At 0635, the Stack ignited fires in the number two fireroom and steamed at one-third speed on her port engine. Ten minutes later, she was steaming on both engines and making ten knots. Navigation was difficult with the gyrocompass out, the magnetic compass damaged, and the stars obscured by fog and clouds. Relying on dead reckoning, the Stack headed for Norfolk as ordered, but, as her feedwater began salting up, changed course to Philadelphia Naval Shipyard. She entered Drydock No. 1 for two months of repairs under a shroud of secrecy. “It might have been secret,” said Lilly, “but the entire shipyard ate lunch sitting around the drydock gazing at our disabled ship being patched up.”

As Lilly, who earned a Purple Heart at the Battle of Surigao Strait during World War II, a Bronze Star with Combat “V” during the Korean War Siege of Wonsan (see “The Siege of Wonsan,” pp. 28–35), and two Legions of Merit during the Vietnam War before retiring in 1970 as a captain, summed up the experience: “It was pretty damn frightening. At first we were dead in the water and helpless. When we got underway, we were too slow to evade U-boats. We were sitting ducks. I can tell you it was more frightening than when I was attacked by kamikazes in the Pacific.”

Why did the collision occur? The Navy’s investigation into the circumstances of the incident found errors made by the Wasp’s officers bewildering and inexplicable.

Two officers were on the Wasp’s bridge. The OOD was Ensign Thomas R. Weschler, who had been on board the ship for two months and whose total sea experience amounted to eight months. His supervising officer was Commander Donald F. Smith, the carrier’s navigator.

The captain’s night orders required the OOD to inform the captain “in case of any sign of thick weather or considerably reduced visibility.” At 0445, with visibility down to 1,000 yards, the captain was called. Reeves ordered forward fog lookouts posted. However, when visibility closed to “100 yards or less” at 0510, Commander Smith declined the OOD’s recommendation that he notify the Wasp’s captain.17

At 0542, the two forward fog lookouts reported to the Wasp’s bridge that the carrier had collided with “one of our destroyers.”18

A competent OOD would have immediately stopped and told the CO. Instead, the OOD reduced the Wasp’s speed to 15 knots. The Board of Investigation found that “although the collision was duly reported to the Supervisory Officer and to the Officer-of-the-Deck of the Wasp, these officers at first failed to understand the situation correctly.”19

The Commander-in-Chief, Atlantic Fleet, concluded:

The record is clear that a report of collision was received on the Bridge almost at the moment of collision but that its import was not appreciated by the navigator. Prompt and corrective action was not taken. Time was wasted in trying to “verify” the fact that there had been a collision. The collision occurred at 0542, and the engines were not ordered stopped until 0548. At this time, they were ordered ahead 15 knots immediately. The engines were not backed until 0553 and then only at two-thirds speed, instead of emergency. It is a wonder that the Stack was not broken in two or capsized by being pushed sideways by the Wasp.20

The ship logs are in conflict about when the Wasp backed clear.21 What saved the Stack were the sharp angle of the collision and the difference in speed between the two ships of only one-half knot.22

Why were the Wasp’s ranges and bearings wrong and why did the Stack wind up off the carrier’s port bow when her station was to starboard? First, radar in 1942 was in its infancy, and the Wasp’s search and fire-control radar systems had only recently been installed on 1 January 1942. The proficiency of the Wasp’s radar operators was considered “average but not expert.”23

Significantly, neither radar system was accurate in short ranges. Within 1,700 yards “no reading whatever is obtained” from the search radar, and the fire-control radar was difficult to operate in search mode. Radar also was less reliable in the dense fog and humid conditions that prevailed at the time of the collision.24 Inexplicably, Reeves was unaware of these limitations.25

Two reasons were advanced as to why the Stack wound up on the Wasp’s port bow when both ships were on the same course and speed. The first is that the Wasp’s gyrocompass was likely in error.26 The second is that the Wasp’s navigator and OOD never verified whether their “helmsman, who was alone in the conning tower, was [steering] the correct true course.”27

Although Lilly feared Olch would be blamed, no one on board the Stack was faulted. Nor was the Wasp’s OOD, because of his “limited experience” and “he demonstrated a greater appreciation . . . of the situation than did the navigator.”28

The Secretary of the Navy issued a letter of admonition to Captain Reeves and a letter of reprimand to Commander Smith. The punishments may not have been more severe because “the collision was incident to night wartime operations in waters where enemy submarines were known to be operating.”29

In fact, none of the involved officers had their careers adversely affected by the collision.

• Reeves became a rear admiral in 1942, vice admiral on 1 April 1949, and, on retirement in 1950, a four-star admiral.

• Olch became a commander on 30 June 1942 and a captain on 1 April 1943. During the war he was awarded a Bronze Star.

• Ensign Weschler had a successful Navy career during World War II and the Korean and Vietnam wars and rose to the rank of vice admiral.

• Commander Smith was promoted to captain. His last assignment was as Commander, Naval Air Station Quonset Point, Rhode Island.

• Ensign McMullen left the Navy in 1950 as a commander and enjoyed a successful career as president and CEO of United States Lines and as owner of the New Jersey Devils hockey team and the Houston Astros baseball team.30

The Stack served with distinction throughout the war and was damaged during the Bikini Atoll atomic bomb tests. Her service ended in 1948.

The Wasp, however, was not so fortunate. Dubbed “‘Snafu Maru’ because of her propensity for mild misfortune,” she was mortally wounded by torpedoes from a Japanese submarine on 15 September 1942.31 Weschler survived by swimming to safety. Coincidentally, the Stack had detached from the Wasp just one day earlier.

As for Tony Lilly—his Irish blood brought him luck on that Saint Patrick’s Day 1942, as well as to this author, his son, who was born four years later.

1. As Tony Lilly related to the author and wrote in his unpublished memoir, A Sailor’s Life.

2. Barrett Tillman, Enterprise: America’s Fightingest Ship and the Men Who Helped Win World War II (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2013), 170.

3. Ed Offley, “The Drumbeat Mystery,” Naval History 36, no. 1 (February 2022): 14.

4. “Collision USS Wasp–USS Stack,” report of Stack commanding officer to Commander, Task Force 22, RG 38, National Archives and Record Administration (hereafter NARA), College Park, MD, 18 March 1942, 1.

5. “Collision USS Wasp–USS Stack.”

6. “Collision USS Wasp–USS Stack,” 2.

7. “Collision USS Wasp–USS Stack,” 2.

8. Defense Mapping Agency, Sailing Directions (Planning Guide & Enroute) for Antarctica (Bethesda, MD: Defense Mapping Agency, Hydrographic/Topographic Center, 1992),119.

9. Don Silvershield, “Historical Sketch USS Stack,” 29 December 1945, 3.

10. Silvershield, “Historical Sketch USS Stack.”

11. “Collision USS Wasp–USS Stack,” 3.

12. Silvershield, “Historical Sketch USS Stack,” 3.

13. “Frank LeRoy Knight,” The Hall of Valor, https://valor.militarytimes.com/hero/21313.

14. “Collision USS Wasp–USS Stack,” 2.

15. Silvershield, “Historical Sketch USS Stack,” 3.

16. “Collision USS Wasp–USS Stack,” 3.

17. Department of the Navy, “Board of Investigation—Circumstances Attending the Collision between the USS Wasp and the USS Stack,” testimony of Ensign Weschler, RG 125, NARA, 20 March 1942, 16, 17.

18. “Board of Investigation,” testimonies of Seamen Leo Allen, Carl Cartwright, James Heiple, and George Getzloff, 24, 26, 27, 34.

19. “Board of Investigation,” testimony of CAPT Reeves, 4.

20. “Board of Investigation,” endorsement by CINCLANTFLT, 2.

21. The Stack’s deck log and Olch’s testimony state the Wasp backed at 0610. The Wasp’s log and the investigation claim it backed at 0553.

22. “Board of Investigation,” testimony of LCDR Olch, 55.

23. “Board of Investigation,” testimony of LT E. C. Paradise, 41.

24. “Board of Investigation,” testimony of LT E. C. Paradise, 41.

25. “Board of Investigation,” testimony of CAPT Reeves, 7.

26. “Board of Investigation,” endorsement by Commander Service Force, U.S. Atlantic Fleet (CINCLANTFLT), VADM F. L. Reichmuth, USN.

27. “Board of Investigation,” endorsement by CINCLANTFLT, 2.

28. “Board of Investigation,” CINCLANTFLT summary of findings, 3.

29. “Board of Investigation,” endorsement by Commander of Carriers, RADM E. D. McWhorter.

30. “San Pedro News,” 26 May 1942, 3; Register of Commissioned and Warrant Officers of the United States Navy and Marine Corps, Bureau of Naval Personnel, 1 January 1951, 806; “Isaiah Olch, USN,” Uboat.net; All Hands, May 1947, 48; “Weschler, Thomas R., Vice Adm., USN (Ret.),” U.S. Naval Institute Oral History Program; and “John J. McMullen Dies at 87,” The New York Times, 18 September 2005.

31. Patrick Abazzia, Mr. Roosevelt’s Navy: The Private War of the U.S. Atlantic Fleet, 1939–1942 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2016), 206.